Search

Recent comments

- success....

2 hours 51 min ago - seriously....

5 hours 35 min ago - monsters.....

5 hours 42 min ago - people for the people....

6 hours 19 min ago - abusing kids.....

7 hours 52 min ago - brainwashed tim....

12 hours 12 min ago - embezzlers.....

12 hours 18 min ago - epstein connect....

12 hours 29 min ago - 腐敗....

12 hours 49 min ago - multicultural....

12 hours 55 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

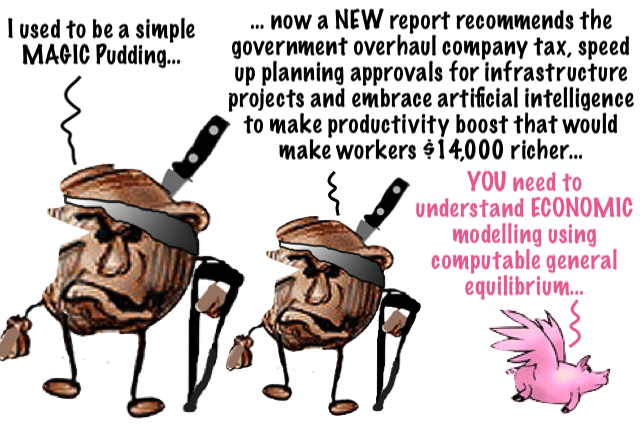

modelling magic dust on the round table of an economists' bunch....

The warm-up for next month’s three-day economic roundtable has begun, and this week we’ll start hearing from worthies who know exactly what we should do to improve our productivity. What’s more, they have the modelling to prove it.

Roundtable warning: When they say ‘modelling’ grab your bulldust detector

Did you see last week’s headline that “ Productivity boost would make workers $14,000 richer”? It was attached to the news that this week Productivity Commission boss Danielle Wood will release a report recommending the government overhaul company tax, speed up planning approvals for infrastructure projects and embrace artificial intelligence.

And doing this would lead to Australia’s full-time workers being $14,000 a year better off within a decade, would it? Well, no. That’s not what she said. It was that if our productivity performance could return to its long-term average, then that would translate into every full-time worker being $14,000 a year better off by 2035.

So, there was no actual link between what she wanted us to do and this mere calculation of what a return to the higher rate of productivity improvement in our past would do to our pay cheques in the present.

But even this simple calculation assumes that, should a return to a higher annual rate of improvement in productivity come about, the workers would get their fair share of the proceeds.

My point is, we’re about to hear many worthies proposing we do more of this or more of that particular thing because it will improve the economy’s “productivity” – its ability to turn the same quantity of labour, capital equipment and raw materials into a greater quantity of goods and services than before.

Sometimes they’ll advocate change X because they genuinely believe it would make the rest of us better off, and sometimes it’s just themselves they’re hoping to benefit. But, either way, many of them will try to make their argument more persuasive by producing “modelling” showing how much better off we’d be.

Let me tell you something, the politicians, businesspeople and economists who wave it in our faces never bother to: modelling isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It can’t tell you much you didn’t already know except the answer to very complicated sums.

It allows to you to say, “if I assume A, B, C … and K, what would that do to the rate of economic growth, employment and incomes, given that the economy works the way economic theory says it does?”

There’s a class of modelling using “computable general equilibrium” (CGE) models that’s very popular in Australia, though less so overseas. These models are often used to measure the likely effects of a change in government policy or of a proposed major infrastructure project.

It’s a safe bet we’ll be told the results of a lot of such modelling exercises before, during and after the roundtable. Just remember that modelling is more about helping me sell my idea to you than about finding out whether my great idea would actually work and, if so, how well.

The problem with economists is that they’re much more about religious faith than scientific inquiry. Our economics profession’s leading sceptic is Dr Richard Denniss, director of the Australia Institute. Other economists know what he knows and share his reservations, but they keep it to themselves.

With Matt Saunders, Denniss has written a paper on the limits of CGE modelling, which would make enlightening reading for many. “General equilibrium” means the model is designed to take in the whole economy, not just one part of it.

“Part of the persuasive power of CGE models comes from the perception that they contain a large amount of objective mathematics and theory,” they say. But while these models “contain many equations, this is not the same thing as a large amount of objectivity".

“The modeller needs to make decisions about the values of thousands, potentially millions, of model variables. It is not the model that estimates the many inputs for which no good data is available, it is the modeller and the modeller’s client that makes such choices.”

One way of viewing the economy is to say that the growth in real gross domestic product is determined by “the three Ps”: population growth, the proportion of the population that participates in the labour force, and the rate of improvement in the productivity of labour.

With these models, all three of those Ps are “exogenous variables”. That is, the modeller makes their best guess on what will happen to population growth, the rate of participation and the rate improvement in labour productivity, then punches them into the model and turns the handle to see what it says will happen to economic growth, employment and all the rest.

This means modelling can tell us little about productivity. If you had a list of things you wanted to do because you thought they’d improve productivity, the model couldn’t tell you whether each of them really would improve productivity, nor by how much all of them would improve it.

So, for instance, modelling can’t tell us whether cutting the rate of company tax would do more for productivity than, say, doubling government support for research and development. When it comes to productivity, it’s always the modeller telling the model what to think, not the other way around.

The great contradiction of modelling is that, while you have to be really good at maths to run a model, let alone build one, and really good at economics to build one that makes sense, the economy you end up modelling is so grossly oversimplified it’s like a world inhabited by stick figures.

Unlike all the people happily quoting modelling results to us, Denniss and Saunders tell us that, although these models spit out many numbers with dollar signs in front of them, there is no actual money in the model, no interest rates, credit, loans or savings.

The models usually assume that inflation has no effect on the real economy, most assume that the profits in each industry are minimal because competition competes them down, and capital equipment can be repurposed at no cost.

It’s fortunate for economists that their profession has never worried too much about ethics.

Republished from Sydney Morning Herald, 28 July 2025

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 30 Jul 2025 - 8:26am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

nuances...

Roger Beale

Tax, productivity growth and equalityTreasurer Jim Chalmers’ upcoming economic summit has triggered renewed debate over the links between tax, productivity, growth and equity. And inevitably arguments between the right and the left – can we understand both and find a way through? I hope so.

From the political right, Robert Carling of the Centre for Independent Studies warns that Australia risks drifting into a “European-style welfare state” of higher taxes, slower growth, and dependency. The CIS opposes any tax increases. Instead, it advocates for a simpler personal income tax (PIT) system with lower top rates and bracket indexation, and calls for cuts to government spending – particularly on the NDIS, aged care, health and childcare. Defence, it argues, should remain a priority. Some on the right also support broadening the Goods and Services Tax base and increasing the rate.

On the left, the Australian Council of Social Service contends that Australia is not raising enough revenue to meet its social and environmental obligations. It strongly opposes shifting the tax mix toward the GST, warning that such a change would disproportionately affect low-income households. ACOSS also questions whether transfers alone could adequately offset these effects.

Despite deep disagreements, there is consensus that rising debt is unsustainable. Both sides recognise that structural deficits threaten future generations and fiscal stability.

This raises a key question: which path supports sustainable growth and fairness – raising revenue through progressive PIT and closing concessions (like those on superannuation, capital gains and negative gearing), or shifting the tax mix toward consumption while limiting spending growth?

We typically assess the tax system through five lenses:

Former senior public servant Mike Keating AC is blunt: revenue must rise. As he notes, the main spending areas — health, education, welfare, infrastructure and defence — are politically and socially difficult to cut. Past savings efforts focused on tightening eligibility or increasing user charges, but future opportunities are limited. (Pearls and Irritations 2018) Defence spending will rise. An ageing population will push pension, aged care and health costs higher. And the climate transition demands sustained public investment.

Australia remains a low-tax country by OECD standards, with only Mexico, Chile, South Korea, the US and Switzerland collecting less tax relative to GDP. Would increasing the tax take necessarily hinder growth?

According to ACOSS and many economists, the answer is no. Cross-country data reveals no strong link between overall tax levels, top PIT rates and GDP per capita – whether measured at market exchange rates, in PPP terms, or per hour worked. Similarly, there is no statistically strong link between tax levels and Human Development Index outcomes. Public goods like health and education are certainly HDI drivers, but other structural and historical factors often matter more. Australia, for example, performs well on HDI (and better than the US) despite a relatively low tax take – though the Nordic countries consistently do better still.

Empirical evidence also shows that cutting top tax rates increases inequality, without boosting growth or employment. As Hope and Limberg (2022) conclude: “Tax cuts for the rich lead to higher income inequality in both the short- and medium-term. In contrast, such reforms do not have any significant effect on economic growth or unemployment.” Piketty writes persuasively about this and the need to tackle inequality (see particularly “Capital in the Twenty-First Century”).

However, it’s not an open-and-shut case. Longitudinal and panel studies show that higher PIT progressivity, especially targeting the top quintile, can slow productivity and reduce real per capita GDP. Jalles and Karras (2025) find that increases in tax progressivity are linked to lower growth and income levels, consistent with neoclassical models. These effects are statistically significant and persistent.

Corporate tax rates have a dominant influence on PIT settings. High differences between the two rates can encourage avoidance through an emphasis on stock incentives for top executives, with high earners and even middle income tradies restructuring income through corporations — a trend seen in sectors like construction. As corporate tax competition continues globally, pressure on top PIT rates may intensify, despite the 2021 OECD agreement on a 15% minimum corporate rate. Trump is weaponising foreign taxes on US corporations.

In theory, high marginal tax rates might reduce work or investment incentives. In practice, outcomes depend on context – such as labour market structure, public services, human capital and behavioural responses. While macro-level relationships are often weak, micro-level evidence still matters. Sector-specific disincentives don’t always scale up neatly to national trends, but they do point to risks that tax policy must manage carefully.

In sum, tax policy should be designed with nuance, not ideology. Badly designed or regressive taxes can hurt growth and fairness. But a well-structured progressive system — especially when aligned with quality public investment — can support both economic strength and social cohesion.

But we mustn’t forget – at the end of the day, tax reform is about the sort of society we want. Equality matters to me and I, for one, am not horrified at the prospect of becoming a “European-style welfare state” but with uniquely Australian nuances.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/07/tax-productivity-growth-and-equality/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.