Search

Recent comments

- peer pressure....

8 hours 12 min ago - strike back....

8 hours 17 min ago - israel paid....

9 hours 20 min ago - on earth....

13 hours 50 min ago - distraction....

15 hours 46 sec ago - on the brink....

15 hours 10 min ago - witkoff BS....

16 hours 24 min ago - new dump....

1 day 4 hours ago - incoming disaster....

1 day 4 hours ago - olympolitics.....

1 day 4 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

and allergic to synthetic perfumes as well...

There are people who splash themselves with cheap benzene derivative perfumes. I stay clear. There are also some cleaners and detergents laced with artificial fragrances like "pine mountains" and "fresh sea breeze"... I stay clear as well — and use water and ordinary turps. Lovely. It reminds me I have to go and paint another masterpiece...

In petrol products, some smells and colours are added in order to make them distinguishable. These are the killers, often used by poor kids who "sniff petrol". Avgas has none of those and does not create a "high" when inhaled. Some people are more sensitive to what has been defined as the modern environment, full of stuff we don't know the effects of...

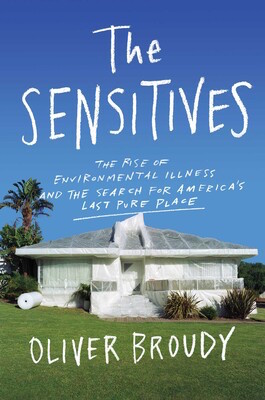

Enter the world of... A compelling exploration of the mysteries of environmental toxicity and the community of “sensitives”—people with powerful, puzzling symptoms resulting from exposure to chemicals, fragrances, and cell phone signals, that have no effect on “normals.”

They call themselves “sensitives.” Over fifty million Americans endure a mysterious environmental illness that renders them allergic to chemicals. Innocuous staples from deodorant to garbage bags wreak havoc on sensitives. For them, the enemy is modernity itself.

No one is born with EI. It often starts with a single toxic exposure. Then the symptoms hit: extreme fatigue, brain fog, muscle aches, inability to tolerate certain foods. With over 85,000 chemicals in the environment, danger lurks around every corner. Largely ignored by the medical establishment and dismissed by family and friends, sensitives often resort to odd ersatz remedies, like lining their walls with aluminum foil or hanging mail on a clothesline for days so it can “off-gas” before they open it.

Broudy encounters Brian Welsh, a prominent figure in the EI community, and quickly becomes fascinated by his plight. When Brian goes missing, Broudy travels with James, an eager, trusting sensitive to find Brian, investigate this disease, and delve into the intricate, ardent subculture that surrounds it. Their destination: Snowflake, the capital of the EI world. Located in eastern Arizona, it is a haven where sensitives can live openly without fear of toxins or the judgment of insensitive “normals.”

While Broudy’s book is wry, pacey, and down-to-earth, it also dives deeply into compelling corners of medical and American history. He finds telling parallels between sensitives and their cultural forebears, from the Puritans to those refugees and dreamers who settled the West. Ousted from mainstream society, these latter-day exiles nonetheless shed bright light on the anxious, noxious world we all inhabit now.

Read more:

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Sensitives/Oliver-Broudy/9781982128500

- By Gus Leonisky at 31 Jul 2020 - 7:34am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

plastic-man is sicko...

...

By way of introduction, Broudy notes that there are, at present, 85,000 synthetic chemicals circulating in our daily environments, including 9000 food additives, the vast majority of which have never been tested for potential effects on humans. In 2017 alone, 3.9 billion pounds of chemicals were dumped into the environment, he notes. Meanwhile, billions of metric tons of plastics (8.3 billion in 2015) accumulate around us. Cancer rates have also spiked, notes Broudy, and he cites drastic increases in other conditions, from autism to allergies.

Enter the “sensitives,” as they call themselves, who report an array of chronic symptoms, most commonly fatigue, memory impairment, and muscle aches, which they attribute to an increased vulnerability to chemicals and other environmental triggers. But despite the high incidence of environmental illness (EI)—Broudy indicates that as much as 30% of the population may exhibit some environmental hypersensitivity—many nonsufferers, particularly in the medical and scientific communities, wonder if it is even real. To date, no one has identified a definitive biomarker for the disease. The symptoms that sufferers report vary widely, and uncertainty prevails, especially in the published literature. This, in Broudy's view, makes EI the defining disease of our time.

The EI experience can come across as both specific to the individual and highly abstract. Yet Broudy refuses to dismiss the sensitives' accounts of their symptoms. Throughout his exploration, he remains skeptical yet empathetic.

To guide his journey toward understanding EI and those it afflicts, Broudy embarks on a road trip with a sensitive named James, who knows both the disease and the places where sensitives seek relief from their symptoms. Woven throughout the story of their travels, extended reflections reveal the state of past and present research on EI. We learn, for example, about Claudia Miller, a professor of environmental and occupational medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, who has developed a model to understand EI, which she calls toxicant-induced loss of tolerance (TILT). “Miller defined TILT as something like the inverse of addiction,” Broudy writes. “[I]t commenced with an exposure, and the exposure led to sensitivity—the opposite of tolerance. Thereafter, even minimal exposures could provoke outsized effects.” He notes parallels with the “rain barrel” theory, advanced by many sensitives, which holds that each individual has a personal toxicity threshold. Exceed the threshold, and illness follows.

How did we come to live in a world so saturated in synthetic chemicals? To answer this question, Broudy recounts the story of British chemist William Henry Perkin, who, in 1856, discovered how to synthesize a deep-purple dye. Other chemists followed suit, producing a colorful palette of synthetic dyes. “From this rainbow our modern world of industrial chemicals emerged,” writes Broudy. Pharmaceuticals followed from the labs of Bayer and Monsanto, and in 1910 Fritz Haber successfully synthesized ammonia, a feat that won him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and ushered in the era of agricultural chemistry.

As the road trip proceeds, Broudy encounters additional environmental risks: mining operations and power plants fired by coal, for example. He uses this to transition the narrative toward a history of risk assessment, which breezes from the birth of modern insurance to the dawn of nuclear armaments. Here, he draws striking comparisons between EI and other diseases with diffuse etiologies, such as Gulf War illness, posttraumatic stress disorder, and neurasthenia.

In Snowflake, Arizona, Broudy meets a community of sensitives, most of whom—like consumptives in the time of tuberculosis—were drawn to the warm, arid desert air. In representing the diversity of experience and symptomology, Broudy reveals EI to be a highly diffuse disease. His comparison of EI to tuberculosis before Robert Koch's discovery of the bacterium is apt.

Traveling with Broudy, we learn much about an inscrutable disease, the people who live with it, the places where they find relief, and the discursive path through history and environmental health that has brought us to new levels of risk and uncertainty. With a tone that is both thoughtful and humorous, The Sensitives provides a model for how history, philosophy, research, clinical practice, and—above all—patient experience inform meaningful discourse about a disease that resists characterization at all stages.

Science 31 Jul 2020:

Vol. 369, Issue 6503, pp. 513

See also:

advocacy-led pseudo-scientific health studies to promote sugarcrap...