Search

Recent comments

- religious war....

6 hours 48 min ago - underdogs....

7 hours 27 sec ago - decentralised....

7 hours 23 min ago - economy 101....

17 hours 19 min ago - peace....

18 hours 8 min ago - making sense....

20 hours 46 min ago - balls....

20 hours 50 min ago - university semites....

21 hours 38 min ago - by the balls....

21 hours 52 min ago - furphy....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

goons: this is the BBC...

BBC

BBC

The BBC is the final liberal monolith in a British media landscape that has been dragged to the right by Rupert Murdoch and others. The Conservatives seem focused on doing all they can to tame it and bring it under political control. The broadcasting giant, meanwhile, seems intimidated, and has even backed down on occasion, as seen during the flag controversy in March.

Some believe that the BBC, in the 100th year of its existence, is fighting for its very survival. Others believe that such claims are even understated.

And it should be clear to all: This power struggle doesn’t just affect a single broadcaster on an island in the North Atlantic. It affects public broadcasters the world over.

The BBC is the "standard bearer” of public broadcasting, says Noel Curran, head of the European Broadcasting Union. If it falls, it would give governments on the Continent an "excuse to attack” media outlets in their own countries. That, he believes, would guarantee a further poisoning of the public debate, with the consequences long visible in the United States – not just for the media, but for democracy.

Founded on Oct. 18, 1922, as the "British Broadcasting Company,” its primary purpose from the very beginning was that of spreading the British societal and economic model around the world. It was helpful that huge parts of the world were already more or less under London’s control. The year before, Northern Ireland had emerged from the rubble of the Irish War of Independence, resulting in the United Kingdom in the form we know today. The Empire was at its zenith, with every fourth person in the world subject to the monarch in London.

Europe, meanwhile, was a hotbed of instability, with not everybody as excited as the British about capitalism and globalization. There were hunger marches in Britain, and women – horror of horrors – could even vote. In some London circles, there were fears that Bolsheviks could use this obscure new broadcasting technology to launch a revolution.

The BBC – nominally independent, but dependent both financially and otherwise on the benevolence of the state – was there to keep things together. The man responsible for it all was John Reith, a Calvinist from Scotland with authoritarian tendencies and little understanding of the new technology. Later, the BBC’s first director general would admit: "The fact is, I hadn’t the remotest idea as to what broadcasting was.”

He quickly discovered, though, how powerful was the instrument over which he had been granted control. Reith believed that the BBC’s responsibility was that of bringing "into the greatest possible number of homes everything that is best in every department of human knowledge.” The broadcaster was a great democratic integrator, he believed, with everyone equal before it: "The genius and the fool, the wealthy and the poor listen simultaneously. There is no first and third class.”

As a motto for the new company, Reith chose: "Inform, educate, entertain.” It remains so to this day.

In its early days, though, the BBC didn’t quite live up to the later ideal of independent, unflinching journalism. There was censorship, for example, with Reith himself imposing it. He wanted the broadcaster to imagine its typical listener to be a respectable, older churchgoer. Moderators and singers on the BBC were prohibited of making references to alcohol and all manner of vulgarity was prohibited, as were political insinuations, meaning anything that deviated from the political mainstream.

Coverage of the 1926 general strike thus made it sound as though the broadcaster was the voice of the government, earning the BBC its first unflattering nickname: "British Falsehood Corporation.”

Colonialism and the MonarchyEven the great Winston Churchill, who wasn’t yet as great as he would become, was essentially silenced by the BBC in the 1930s when he produced a radio series on British domestic and foreign policy. The government of fellow Tory Neville Chamberlain didn’t trust the backbencher Churchill, and the feeling was mutual.

To keep negative influences at arm’s length from the broadcaster, Reith even opened the doors of the Broadcasting House to the MI5. From 1935 onwards, domestic intelligence agents sat in Room 105 and checked out the suitability of incoming journalists. Those who were too far to the right or left stood no chance of being hired.

When the still ongoing practice was uncovered in 1985, BBC leadership expressed contrition. Only to allow her majesty’s spies to continue their work for several more years.

More than anything, though, Reith consistently took seriously the first B in the BBC. Nothing could be allowed to shake the pillars of Britain’s global hegemony – the empire and the monarchy first and foremost. If only very few in today’s Britain question colonialism and the monarchy, it is partly because the extended BBC broadcasting monopoly never questioned it either.

Instead, reports on the kingdom’s expansion tended to be a bit inexact. Here, for example, is a passage from a 1928 geography show for schoolchildren: "The British Empire was not won by fighting. Australia is ours purely by settlement. New Zealand was handed over to us, of their own free will, by the Maoris. South Africa was bought from the Dutch and in Canada, the only part that was conquered was Quebec.” Right.

Since then, "Auntie,” as the BBC is sometimes known, has come a long way. The broadcaster grew, as did the self-confidence of its employees and the trust of its listening (and viewing) public. It emancipated itself to the degree possible from political influence and developed a critical journalistic approach, an exemplary one in many respects. It no longer only reported on the pillars of the United Kingdom. Rather, it became one itself.

Today, the BBC is a media empire like no other. It employs around 22,000 people, including over 2,000 journalists, and broadcasts 24 hours a day in Britain and around much of the world. It has 10 national television and radio stations along with dozens of regional and local stations. The BBC World Service broadcasts in more than 40 languages and has correspondents in virtually every corner of the world.

The company maintains five symphony orchestras, a professional choir and a Big Band. For the last 94 years, it has produced the classical music festival BBC Proms. It has filmed all of Shakespeare’s dramas and has published numerous books – and it has been the subject of numerous books as well. George Orwell, once a BBC journalist himself, memorialized the Broadcasting House perhaps a bit unflatteringly as the "Ministry of Truth” in his novel "1984.”

In the early days of the digital era, the company even developed its own computer, the BBC Micro. Using the priceless footage of its Natural History Unit, it focused on the fragility of our globe in the series "Planet Earth.”

Through the years, it has produced a steady stream of legendary series and programs, like "Civilization,” "I, Claudius,” "Doctor Who,” "Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” and, more recently, "Fleabag” and "Line of Duty.” With "Top of the Pops,” it produced the most important pop-music show of its time. When it launched on Jan. 1, 1964, the show hosted The Beatles along with a promising young band called The Rolling Stones.

Most of what the world knows about the British, it knows from the BBC.

Even what the British know about the British comes largely from Auntie – through shows like "Gardeners’ World,” "Yes, Minister,” "Fawlty Towers,” and "The Great British Bake Off.” In the mirror of BBC, her majesty’s subjects were able to recognize themselves, and they liked what they saw: quirky, peace-loving hedge-trimmers with unending humor and a sense for good manners – to go with a grandiose history. Back when everyone used to watch TV at the same time, the good old BBC created a sense of community.

Collective OutrageAlong with power, though, came difficulties. The BBC became akin to a public authority, both arrogant and anxious – and overly bureaucratic. Insiders say sardonically that one of the BBC’s largest departments is the one for the prevention of good ideas.

The BBC also became home to controversy and scandal. There were bitter fights over the coverage of the Falkland War, the Iraq War, the Scottish independence referendum and Brexit. There was the unmasking of star moderator Jimmy Savile, who had abused hundreds of children over the decades, and now the broadcaster is facing the embarrassment over the 1995 Diana interview, which was a coup in part because of Diana’s explosive comment: "There were three of us in this marriage.”

Recently, an independent investigation reached the conclusion that Diana’s interviewer Martin Bashir forged bank statements to suggest that she was under surveillance, thus winning her trust. The BBC, the report notes, sought to cover up "deceitful behavior.”

Collective outrage and multi-year inquiries have been an almost constant companion. And it was never about just any old media company, it was the BBC, a national treasure. The Beeb, though, always managed to recover.

The BBC’s constantly growing influence, however, was frequently a source of unease, particularly in political circles. In part because the BBC consistently expanded its news department. Today, it is far and away the company’s largest department, and BBC political journalists have always been seen as too far to the left or right, depending on who currently resides in Downing Street 10. Margaret Thatcher, who found the BBC to be "quite intolerable,” took on the broadcaster, as did Tony Blair. The threat has always been the same: that of cutting down the goliath to normal size. Usually, though, BBC journalists were simply doing their jobs: analytical, critical journalism.

Read more:

assange2

assange2

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Jun 2021 - 8:14am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

from the old ABC stalwarts...

...

Federal treasurer Josh Frydenberg did not attend the meeting at Hawthorn Town Hall on Saturday night, 8 May – he was in Canberra ahead of delivering the Federal Budget on 11 May – but about 450 people did.

However, a message from Mr Frydenberg was read in full to the audience.

After assuring them that the Australian Government is “committed to maintaining the health and vibrancy of the ABC”, the treasurer prompted some laughter and astonishment as he repeated the Coalition’s position that there have been no cuts to the ABC.

Here’s what he said:

“It is important to note that the ABC’s budget has not been cut. ABC funding is locked in for the current three year period or triennium (2019-20 to 2021-22) and rises each year within that period. In the last budget the ABC received a further $43.7 million for regional and local news gathering. As you may already be aware, the government provided funding to the ABC of $1,046 million in 2018-19; in the three years of the current triennium, the ABC is receiving $1,062 million (2019-20); $1,065 million (2020-21); and $1,070 million (2021-22).”

This is in contradiction to independent research by Sydney University and RMIT which shows that under the Coalition the ABC has lost $783 million in funding since 2014, an average of 10 per cent cut every year.

Read more:

https://abcalumni.net/2021/05/11/its-your-abc-fight-for-it/

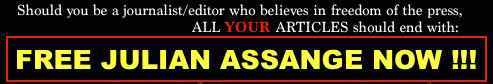

Free Julian Assange Now ©ƒ∂ßßßßßßååååå¡¡¡¡¡!!!!!!

A great cartoon by Moir (SMH 5/6/2021):