Search

Recent comments

- meanwhile....

55 min 41 sec ago - a long day....

2 hours 49 min ago - pressure....

3 hours 37 min ago - peer pressure....

18 hours 56 min ago - strike back....

19 hours 2 min ago - israel paid....

20 hours 4 min ago - on earth....

1 day 34 min ago - distraction....

1 day 1 hour ago - on the brink....

1 day 1 hour ago - witkoff BS....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

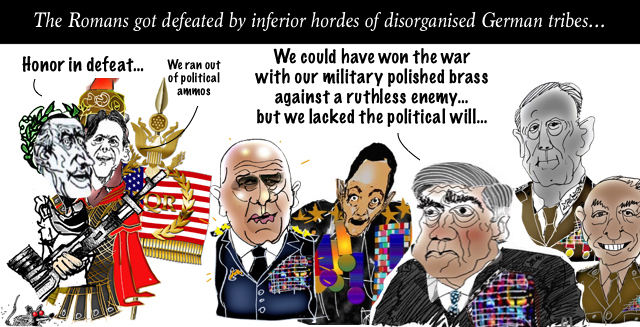

the generals versus the US administrations...

romans

romans

This is a fictitious interview between the last brass standing and an "intelligence” lamppost disguised a a journalist from the New York Washington Clarion, collected by Gus the Elder — on the post-mortem of a retreat gone apecrap.

Journo: — Could the Taliban have been defeated?

Brass: — Of course…

— So, what happened?

— I guess our “forever war” on-going system was responsible for the “defeat”… See if you defeat your enemies completely, you have no need for a gigantic army with a million contractors manufacturing complex weapons systems and bombs… Eventually, one gets tired of “forever” routine on the same spot… We need a change of landscape and motivations… We’re changing location.

— is this why the retreat was a bit half-hearted? A debacle so to speak?

— No, we’re just useless trying to get out of a paper bag...

— Is Donald Trump to blame for having made a deal with the Taliban rather than with the Afghan government?

— Sure, Trump is to be blamed for everything that goes wrong in America… till at least the turn of the next century.

— So, how could you defeat an enemy completely?

— Destroy entire populations, including under-aged prospective terrorists and ankle-biters. Destroy their international friends — those we unfortunately need to defeat Iran next...

— And use the art of warfare?

— No artistry there… we just neded to be arseholes and follow the tactics of invaders like Genghis khan: pillage, rape, kill civilians… loot, steal… Burn, slash, napalm, phosphorus!

— But we don’t do that?

— Exactly. This is why we do “containment” instead of outright victory… We’re a bit too kind, morally… Ours was not a defeat but a moral victory full of kindness towards ruthless people… We had built a useless puppet corrupt government and an even more useless local army — so they needed us to stay. At 5 to 1 superiority with US latest weaponry, we only trained the local army in handling guns, marching in step and keeping uniforms clean, but not in the subtle art of fighting for real… One does not want dirt and blood stains spoiling the parades...

— Is this the style of threat we're planning against Russia and China?

— Not quite… We’ll bomb them out of existence… They REALLY give us the shits and threaten our moral kindness…

— and we would prevail?

— of course, but there might not be enough wild caves for our remaining small population to live in afterwards…

— any benefits?

— no one dies from global warming during a nuclear winter...

— Thany you...

- By Gus Leonisky at 2 Sep 2021 - 9:39am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

polishing the cats...

The top US general has described the Taliban as a "ruthless group" and says it is unclear whether they will change.

Gen Mark Milley said, however, it was "possible" that the US would co-ordinate with the Islamist militants on future counter-terrorism operations.

US forces withdrew from Afghanistan on Tuesday, ending America's longest war 20 years after launching an invasion to oust the Taliban.

The Islamists are now in control and expected to announce a new government.

Gen Milley was speaking alongside US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin, in their first public remarks since the last troops left Afghanistan.

US President Joe Biden has been widely criticised over the abrupt manner of the US withdrawal, which led to the unexpected collapse of the Afghan security forces US troops had trained and funded for years.

The Taliban's lightning advance sparked off a frenetic effort to evacuate thousands of foreign nationals and local Afghans who had been working for them.

In the news conference on Wednesday, both Gen Milley and Secretary Austin praised the troops who served in Afghanistan and the massive evacuation mission.

Asked about their co-ordination with the Taliban in getting evacuees to the airport, Mr Austin said: "We were working with the Taliban on a very narrow set of issues, and that was just that - to get as many people out as we possibly could."

Regarding future co-operation, he said: "I would not make any leaps of logic to broader issues."

"In war you do what you must in order to reduce risk to mission and force, not what you necessarily want to do," Gen Milley added.

In total, the evacuation operation saw more than 123,000 people wishing to flee the Taliban regime airlifted out of the country.

The US estimates that there are between 100 and 200 Americans still in Afghanistan.

US Under-Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland said "all possible options" were being looked at to get remaining US citizens and people who worked with the US out of the country.

Meanwhile, UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said he was not certain how many UK nationals remained in the country, but that it was believed to be in the "low hundreds".

The Taliban have celebrated the final withdrawal of foreign forces, and are now focusing on forming a government.

The deputy head of the Taliban's political office in Qatar, Sher Abbas Stanekza, told BBC Pashto that a new government could be announced in the next two days.

He said there would be a role for women at lower levels but not in very senior positions.

He also said that those who served in government in the past two decades would not be included.

Read more:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-58415877

army failure is a weird mistress...

The crux of the matter in failures... is explained in 2011 by author, reporter and senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, Thomas E. Ricks. Ricks explores national security issues and military history with amazing insight. He has covered the U.S. military for the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. Here in this lecture he gives us insight on how successful the "generals" of war are or not. He also focuses on George Marshall... the US guy who won "WW2 single handedly" (not really but his decisions influence the way WW2 went) — but pissed off General de Gaulle, himself a clever man, a deep student of history and of French freedom...

See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OehvY94N-WA

George Catlett Marshall Jr. GCB (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American soldier and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff under presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, then served as Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense under Truman.[4] Winston Churchill lauded Marshall as the "organizer of victory" for his leadership of the Allied victory in World War II. After the war, he spent a frustrating year trying and failing to avoid the impending civil war in China. As Secretary of State, Marshall advocated a U.S. economic and political commitment to post-war European recovery, including the Marshall Plan that bore his name. In recognition of this work, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.[5]

Born in Pennsylvania, Marshall graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in 1901. Marshall received his commission as a second lieutenant of Infantry in February 1902 and immediately went to the Philippines. He served in the United States and overseas in positions of increasing rank and responsibility, including platoon leader and company commander in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War. He was the Honor Graduate of his Infantry-Cavalry School Course in 1907, and graduated first in his 1908 Army Staff College class. In 1916 Marshall was assigned as aide-de-camp to J. Franklin Bell, the commander of the Western Department. After the nation entered World War I in 1917, Marshall served with Bell who commanded the Department of the East. He was assigned to the staff of the 1st Division, and assisted with the organization's mobilization and training in the United States, as well as planning of its combat operations in France. Subsequently, assigned to the staff of the American Expeditionary Forces headquarters, he was a key planner of American operations including the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

After the war, Marshall became an aide-de-camp to John J. Pershing, who was then the Army's Chief of Staff. Marshall later served on the Army staff, was the executive officer of the 15th Infantry Regiment in China, and was an instructor at the Army War College. In 1927, he became assistant commandant of the Army's Infantry School, where he modernized command and staff processes, which proved to be of major benefit during World War II. In 1932 and 1933 he commanded the 8th Infantry Regiment and Fort Screven, Georgia. Marshall commanded 5th Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division and Vancouver Barracks from 1936 to 1938, and received promotion to brigadier general. During this command, Marshall was also responsible for 35 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Oregon and southern Washington. In July 1938, Marshall was assigned to the War Plans Division on the War Department staff, and later became the Army's Deputy Chief of Staff. When Chief of Staff Malin Craig retired in 1939, Marshall became acting Chief of Staff, and then Chief of Staff, a position he held until the war's end in 1945.

As Chief of Staff, Marshall organized the largest military expansion in U.S. history, and received promotion to five-star rank as General of the Army. Marshall coordinated Allied operations in Europe and the Pacific until the end of the war. In addition to accolades from Churchill and other Allied leaders, Time magazine named Marshall its Man of the Year for 1943 and 1947.[6] Marshall retired from active service in 1945, but remained on active duty, as required for holders of five-star rank.[7] From December 15, 1945 to January 1947, Marshall served as a special envoy to China in an unsuccessful effort to negotiate a coalition government between the Nationalists of Chiang Kai-shek and Communists under Mao Zedong.

As Secretary of State from 1947 to 1949, Marshall advocated rebuilding Europe, a program that became known as the Marshall Plan, and which led to his being awarded the 1953 Nobel Peace Prize.[8] After resigning as Secretary of State, Marshall served as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission[9] and president of the American National Red Cross. As Secretary of Defense at the start of the Korean War, Marshall worked to restore the military's confidence and morale at the end of its post-World War II demobilization and then its initial buildup for combat in Korea and operations during the Cold War. After resigning as Defense Secretary, Marshall retired to his home in Virginia. He died in 1959 and was buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_C._Marshall

It seems that Marshall pass-time was to fire and hire generals at will... IT WAS HIS JOB. Eventually leading to pick Eisenhower as one of "his" generals... The rest is history...

when being a general becomes a job...

The Afghanistan war, conceived in the traumatic aftermath of 9/11 has ended 20 years later in a misconceived traumatic withdrawal.

The escalating violent events bookend a detached extraction of knowledge, encyclopaedic in its scale and inaccessibility. We trust that successive prime ministers will be highly informed on why we go to war and how these wars are conducted. After all, it is them alone who make such grave decisions on our behalf.

But now, as we scramble to access the knowledge of this 20-year gap and all that has gone before, we find ourselves dusting off a profound disconnect with the political process, meaningful participation and a sense of humanity lost. When the dust settles so will the realisation that the books haven’t been read.

The urgency of an escalating humanitarian disaster in Afghanistan was addressed by our prime minister and Defence Minister Peter Dutton through blame-shifting narratives. Fleeing Afghans were framed as potential terrorists with Dutton warning Afghans not to flee on boats. Does he know that Afghanistan is a land-locked country? An atlas is usually included in an encyclopaedia.

The people smuggling framing is a calculated attempt to dehumanise those in dire need – people who may not have the means to access the politically legitimated channels. Especially given the accelerating urgency with the Taliban in power.

At the same time Dutton conceded that not all “legitimate” Afghans who risked their lives to support the Australian Defence Force and other Australian services will be rescued. What options therefore are there for those left behind? Perilous and lengthy journeys on alternative routes into neighbouring countries perhaps, to languish in refugee camps? Freedom must feel a long way off.

To then frame the collapse of the Afghan army as a cowardly betrayal of their country is an insult to 69,000 Afghan soldiers who have been killed in the war. This is another calculated dehumanisation and a blatantly false assessment.

This blunt and brutish narrative is designed to diminish our humanitarian responsibility and deflect scrutiny of our own systemic strategic failings. It illuminates underdeveloped policy considerations when we commit to war. It also shows how compassion for foreign victims comes and goes when it suits a political agenda. lt is a political practice that absolves transparency, accountability and humility, creating a type of moral injury. This is a concept that we don’t yet fully appreciate, but will undoubtedly impact our veteran community more than any politician pulling the frayed strings from above. Moral hazards were rife over the course of this war and our arrogance even moreso.

The failings of some individual factors, the premature closure of the embassy, exasperating timeframes, convoluted and questionable visa eligibility processes, to name a few, will be rightly tossed around in parliament. But an even bigger issue will remain unanswered because it is not asked.

What political mechanisms are available to debate and also have influence on how and why we go to war? There are none. The war power shelf is simply out of reach. Prime ministers alone commit us to war. Red flags in the form of discussion, debate and protest are quickly folded as an even bigger Australian flag is unfolded. Accountability in war simply has no place on the Australian political agenda. Discussion, debate and protest are shafted as unaustralian and anti-troops. Why is it that supporting our troops is reduced to patriotic platitudes and why is that war is justified through lofty and hollow virtues? Supporting our troops is a collective responsibility and war can not be waged through wishful rhetoric.

In the absence of curiosity and critique we don’t get beyond the cover to see the bigger picture. The :Afghanistan Papers” leaked in December 2019 via the Washington Post, reveal years of investigation by SIGAR (Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction) details frontline assessment of the situation in Afghanistan. This evidence was grossly at odds with the shiny progress reports fed to the Australian public over our twenty year mission. The SIGAR report exposes a bipartisan deception that should’ve alarmed us, yet barely made it into parliament debate or media scrutiny. Our political leaders knew that the Afghan government was systemically corrupt and the Afghan police and military capacity to hold back the Taliban was fanciful. It further exposed a mission creep, strategic failings and flaws in our over reliant relationship with the US alliance.

These thoughts and ramblings do not come from a professional expertise perspective. They come from bearing witness, in a place of safety and privilege, of all the lives lost and lives that have never seen peace and stability in Afghanistan. We can’t just shelve and bookend the gut wrenching images and behave like innocent bystanders. We must carry this alarm with purpose and a sense of agency.

The decision to go to war is a serious one with grave consequences and so are all the decisions along the way. A closed book approach to war perpetuates, an ‘in-hindsight’ understanding, When perhaps mistakes and lessons have been before us for sometime. But left in the hands of the executive, they silence critical conversations and amplify ill conceived slogans. In regards to the war in Afghanistan our prime minister has reassured us that the sacrifice of 41 ADF lives was in a “good cause”, “whatever the outcome” is at odds with me and at the cost of 241,000 Afghans who have been killed. The whatever goes mentality has no place in war. Outcomes are important. It’s about time politicians invested more in them and us… and others too.

I want the world to be silent for a moment

So we Afghans can scream our

Our pain in its heart, uninterrupted.

– Shaharzad Akbar

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/why-has-the-good-war-ended-so-badly/

Read from top.

READ FROM TOP

READ FROM TOP... Especially see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OehvY94N-WA

Watch carefully.......... Note : "when being a general becomes a job"... is also valid for "when being a politician becomes a job" and all the PUBLIC values vanish from the heart of politics...

politics, military politics, decision points...

The Rolling Stone profile of Stanley McChrystal that changed history

By

MICHAEL HASTINGS ‘How’d I get screwed into going to this dinner?” demands Gen. Stanley McChrystal. It’s a Thursday night in mid-April, and the commander of all U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan is sitting in a four-star suite at the Hôtel Westminster in Paris. He’s in France to sell his new war strategy to our NATO allies – to keep up the fiction, in essence, that we actually have allies. Since McChrystal took over a year ago, the Afghan war has become the exclusive property of the United States. Opposition to the war has already toppled the Dutch government, forced the resignation of Germany’s president and sparked both Canada and the Netherlands to announce the withdrawal of their 4,500 troops. McChrystal is in Paris to keep the French, who have lost more than 40 soldiers in Afghanistan, from going all wobbly on him.“The dinner comes with the position, sir,” says his chief of staff, Col. Charlie Flynn*.

McChrystal turns sharply in his chair.

“Hey, Charlie,” he asks, “does this come with the position?”

McChrystal gives him the middle finger.

The general stands and looks around the suite that his traveling staff of 10 has converted into a full-scale operations center. The tables are crowded with silver Panasonic Toughbooks, and blue cables crisscross the hotel’s thick carpet, hooked up to satellite dishes to provide encrypted phone and e-mail communications. Dressed in off-the-rack civilian casual – blue tie, button-down shirt, dress slacks – McChrystal is way out of his comfort zone. Paris, as one of his advisers says, is the “most anti-McChrystal city you can imagine.” The general hates fancy restaurants, rejecting any place with candles on the tables as too “Gucci.” He prefers Bud Light Lime (his favorite beer) to Bordeaux, Talladega Nights (his favorite movie) to Jean-Luc Godard. Besides, the public eye has never been a place where McChrystal felt comfortable: Before President Obama put him in charge of the war in Afghanistan, he spent five years running the Pentagon’s most secretive black ops.

“What’s the update on the Kandahar bombing?” McChrystal asks Flynn. The city has been rocked by two massive car bombs in the past day alone, calling into question the general’s assurances that he can wrest it from the Taliban.

“We have two KIAs, but that hasn’t been confirmed,” Flynn says.

McChrystal takes a final look around the suite. At 55, he is gaunt and lean, not unlike an older version of Christian Bale in Rescue Dawn. His slate-blue eyes have the unsettling ability to drill down when they lock on you. If you’ve fucked up or disappointed him, they can destroy your soul without the need for him to raise his voice.

“I’d rather have my ass kicked by a roomful of people than go out to this dinner,” McChrystal says.

He pauses a beat.

“Unfortunately,” he adds, “no one in this room could do it.”

With that, he’s out the door.

“Who’s he going to dinner with?” I ask one of his aides.

“Some French minister,” the aide tells me. “It’s fucking gay.”

The next morning, McChrystal and his team gather to prepare for a speech he is giving at the École Militaire, a French military academy. The general prides himself on being sharper and ballsier than anyone else, but his brashness comes with a price: Although McChrystal has been in charge of the war for only a year, in that short time he has managed to piss off almost everyone with a stake in the conflict. Last fall, during the question-and-answer session following a speech he gave in London, McChrystal dismissed the counterterrorism strategy being advocated by Vice President Joe Biden as “shortsighted,” saying it would lead to a state of “Chaos-istan.” The remarks earned him a smackdown from the president himself, who summoned the general to a terse private meeting aboard Air Force One. The message to McChrystal seemed clear: Shut the fuck up, and keep a lower profile.

Now, flipping through printout cards of his speech in Paris, McChrystal wonders aloud what Biden question he might get today, and how he should respond. “I never know what’s going to pop out until I’m up there, that’s the problem,” he says. Then, unable to help themselves, he and his staff imagine the general dismissing the vice president with a good one-liner.

“Are you asking about Vice President Biden?” McChrystal says with a laugh. “Who’s that?”

“Biden?” suggests a top adviser. “Did you say: Bite Me?”

When Barack Obama entered the Oval Office, he immediately set out to deliver on his most important campaign promise on foreign policy: to refocus the war in Afghanistan on what led us to invade in the first place. “I want the American people to understand,” he announced in March 2009. “We have a clear and focused goal: to disrupt, dismantle and defeat Al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan.” He ordered another 21,000 troops to Kabul, the largest increase since the war began in 2001. Taking the advice of both the Pentagon and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he also fired Gen. David McKiernan – then the U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan – and replaced him with a man he didn’t know and had met only briefly: Gen. Stanley McChrystal. It was the first time a top general had been relieved from duty during wartime in more than 50 years, since Harry Truman fired Gen. Douglas MacArthur at the height of the Korean War.

Even though he had voted for Obama, McChrystal and his new commander in chief failed from the outset to connect. The general first encountered Obama a week after he took office, when the president met with a dozen senior military officials in a room at the Pentagon known as the Tank. According to sources familiar with the meeting, McChrystal thought Obama looked “uncomfortable and intimidated” by the roomful of military brass. Their first one-on-one meeting took place in the Oval Office four months later, after McChrystal got the Afghanistan job, and it didn’t go much better. “It was a 10-minute photo op,” says an adviser to McChrystal. “Obama clearly didn’t know anything about him, who he was. Here’s the guy who’s going to run his fucking war, but he didn’t seem very engaged. The Boss was pretty disappointed.”

From the start, McChrystal was determined to place his personal stamp on Afghanistan, to use it as a laboratory for a controversial military strategy known as counterinsurgency. COIN, as the theory is known, is the new gospel of the Pentagon brass, a doctrine that attempts to square the military’s preference for high-tech violence with the demands of fighting protracted wars in failed states. COIN calls for sending huge numbers of ground troops to not only destroy the enemy, but to live among the civilian population and slowly rebuild, or build from scratch, another nation’s government – a process that even its staunchest advocates admit requires years, if not decades, to achieve. The theory essentially rebrands the military, expanding its authority (and its funding) to encompass the diplomatic and political sides of warfare: Think the Green Berets as an armed Peace Corps. In 2006, after Gen. David Petraeus beta-tested the theory during his “surge” in Iraq, it quickly gained a hardcore following of think-tankers, journalists, military officers and civilian officials. Nicknamed “COINdinistas” for their cultish zeal, this influential cadre believed the doctrine would be the perfect solution for Afghanistan. All they needed was a general with enough charisma and political savvy to implement it.

As McChrystal leaned on Obama to ramp up the war, he did it with the same fearlessness he used to track down terrorists in Iraq: Figure out how your enemy operates, be faster and more ruthless than everybody else, then take the fuckers out. After arriving in Afghanistan last June, the general conducted his own policy review, ordered up by Defense Secretary Robert Gates. The now-infamous report was leaked to the press, and its conclusion was dire: If we didn’t send another 40,000 troops – swelling the number of U.S. forces in Afghanistan by nearly half – we were in danger of “mission failure.” The White House was furious. McChrystal, they felt, was trying to bully Obama, opening him up to charges of being weak on national security unless he did what the general wanted. It was Obama versus the Pentagon, and the Pentagon was determined to kick the president’s ass.

Last fall, with his top general calling for more troops, Obama launched a three-month review to re-evaluate the strategy in Afghanistan. “I found that time painful,” McChrystal tells me in one of several lengthy interviews. “I was selling an unsellable position.” For the general, it was a crash course in Beltway politics – a battle that pitted him against experienced Washington insiders like Vice President Biden, who argued that a prolonged counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan would plunge America into a military quagmire without weakening international terrorist networks. “The entire COIN strategy is a fraud perpetuated on the American people,” says Douglas Macgregor, a retired colonel and leading critic of counterinsurgency who attended West Point with McChrystal. “The idea that we are going to spend a trillion dollars to reshape the culture of the Islamic world is utter nonsense.

In the end, however, McChrystal got almost exactly what he wanted. On December 1st, in a speech at West Point, the president laid out all the reasons why fighting the war in Afghanistan is a bad idea: It’s expensive; we’re in an economic crisis; a decade-long commitment would sap American power; Al Qaeda has shifted its base of operations to Pakistan. Then, without ever using the words “victory” or “win,” Obama announced that he would send an additional 30,000 troops to Afghanistan, almost as many as McChrystal had requested. The president had thrown his weight, however hesitantly, behind the counterinsurgency crowd.

Today, as McChrystal gears up for an offensive in southern Afghanistan, the prospects for any kind of success look bleak. In June, the death toll for U.S. troops passed 1,000, and the number of IEDs has doubled. Spending hundreds of billions of dollars on the fifth-poorest country on earth has failed to win over the civilian population, whose attitude toward U.S. troops ranges from intensely wary to openly hostile. The biggest military operation of the year – a ferocious offensive that began in February to retake the southern town of Marja – continues to drag on, prompting McChrystal himself to refer to it as a “bleeding ulcer.” In June, Afghanistan officially outpaced Vietnam as the longest war in American history – and Obama has quietly begun to back away from the deadline he set for withdrawing U.S. troops in July of next year. The president finds himself stuck in something even more insane than a quagmire: a quagmire he knowingly walked into, even though it’s precisely the kind of gigantic, mind-numbing, multigenerational nation-building project he explicitly said he didn’t want.

Even those who support McChrystal and his strategy of counterinsurgency know that whatever the general manages to accomplish in Afghanistan, it’s going to look more like Vietnam than Desert Storm. “It’s not going to look like a win, smell like a win or taste like a win,” says Maj. Gen. Bill Mayville, who serves as chief of operations for McChrystal. “This is going to end in an argument.”

The night after his speech in Paris, McChrystal and his staff head to Kitty O’Shea’s, an Irish pub catering to tourists, around the corner from the hotel. His wife, Annie, has joined him for a rare visit: Since the Iraq War began in 2003, she has seen her husband less than 30 days a year. Though it is his and Annie’s 33rd wedding anniversary, McChrystal has invited his inner circle along for dinner and drinks at the “least Gucci” place his staff could find. His wife isn’t surprised. “He once took me to a Jack in the Box when I was dressed in formalwear,” she says with a laugh.

The general’s staff is a handpicked collection of killers, spies, geniuses, patriots, political operators and outright maniacs. There’s a former head of British Special Forces, two Navy Seals, an Afghan Special Forces commando, a lawyer, two fighter pilots and at least two dozen combat veterans and counterinsurgency experts. They jokingly refer to themselves as Team America, taking the name from the South Park-esque sendup of military cluelessness, and they pride themselves on their can-do attitude and their disdain for authority. After arriving in Kabul last summer, Team America set about changing the culture of the International Security Assistance Force, as the NATO-led mission is known. (U.S. soldiers had taken to deriding ISAF as short for “I Suck at Fighting” or “In Sandals and Flip-Flops.”) McChrystal banned alcohol on base, kicked out Burger King and other symbols of American excess, expanded the morning briefing to include thousands of officers and refashioned the command center into a Situational Awareness Room, a free-flowing information hub modeled after Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s offices in New York. He also set a manic pace for his staff, becoming legendary for sleeping four hours a night, running seven miles each morning, and eating one meal a day. (In the month I spend around the general, I witness him eating only once.) It’s a kind of superhuman narrative that has built up around him, a staple in almost every media profile, as if the ability to go without sleep and food translates into the possibility of a man single-handedly winning the war.

By midnight at Kitty O’Shea’s, much of Team America is completely shitfaced. Two officers do an Irish jig mixed with steps from a traditional Afghan wedding dance, while McChrystal’s top advisers lock arms and sing a slurred song of their own invention. “Afghanistan!” they bellow. “Afghanistan!” They call it their Afghanistan song.

McChrystal steps away from the circle, observing his team. “All these men,” he tells me. “I’d die for them. And they’d die for me.”

The assembled men may look and sound like a bunch of combat veterans letting off steam, but in fact this tight-knit group represents the most powerful force shaping U.S. policy in Afghanistan. While McChrystal and his men are in indisputable command of all military aspects of the war, there is no equivalent position on the diplomatic or political side. Instead, an assortment of administration players compete over the Afghan portfolio: U.S. Ambassador Karl Eikenberry, Special Representative to Afghanistan Richard Holbrooke, National Security Advisor Jim Jones and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, not to mention 40 or so other coalition ambassadors and a host of talking heads who try to insert themselves into the mess, from John Kerry to John McCain. This diplomatic incoherence has effectively allowed McChrystal’s team to call the shots and hampered efforts to build a stable and credible government in Afghanistan. “It jeopardizes the mission,” says Stephen Biddle, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who supports McChrystal. “The military cannot by itself create governance reform.”

Part of the problem is structural: The Defense Department budget exceeds $600 billion a year, while the State Department receives only $50 billion. But part of the problem is personal: In private, Team McChrystal likes to talk shit about many of Obama’s top people on the diplomatic side. One aide calls Jim Jones, a retired four-star general and veteran of the Cold War, a “clown” who remains “stuck in 1985.” Politicians like McCain and Kerry, says another aide, “turn up, have a meeting with Karzai, criticize him at the airport press conference, then get back for the Sunday talk shows. Frankly, it’s not very helpful.” Only Hillary Clinton receives good reviews from McChrystal’s inner circle. “Hillary had Stan’s back during the strategic review,” says an adviser. “She said, ‘If Stan wants it, give him what he needs.’ ”

McChrystal reserves special skepticism for Holbrooke, the official in charge of reintegrating the Taliban. “The Boss says he’s like a wounded animal,” says a member of the general’s team. “Holbrooke keeps hearing rumors that he’s going to get fired, so that makes him dangerous. He’s a brilliant guy, but he just comes in, pulls on a lever, whatever he can grasp onto. But this is COIN, and you can’t just have someone yanking on shit.”

At one point on his trip to Paris, McChrystal checks his BlackBerry. “Oh, not another e-mail from Holbrooke,” he groans. “I don’t even want to open it.” He clicks on the message and reads the salutation out loud, then stuffs the BlackBerry back in his pocket, not bothering to conceal his annoyance.

“Make sure you don’t get any of that on your leg,” an aide jokes, referring to the e-mail.

By far the most crucial – and strained – relationship is between McChrystal and Eikenberry, the U.S. ambassador. According to those close to the two men, Eikenberry – a retired three-star general who served in Afghanistan in 2002 and 2005 – can’t stand that his former subordinate is now calling the shots. He’s also furious that McChrystal, backed by NATO’s allies, refused to put Eikenberry in the pivotal role of viceroy in Afghanistan, which would have made him the diplomatic equivalent of the general. The job instead went to British Ambassador Mark Sedwill – a move that effectively increased McChrystal’s influence over diplomacy by shutting out a powerful rival. “In reality, that position needs to be filled by an American for it to have weight,” says a U.S. official familiar with the negotiations.

The relationship was further strained in January, when a classified cable that Eikenberry wrote was leaked to The New York Times. The cable was as scathing as it was prescient. The ambassador offered a brutal critique of McChrystal’s strategy, dismissed President Hamid Karzai as “not an adequate strategic partner,” and cast doubt on whether the counterinsurgency plan would be “sufficient” to deal with Al Qaeda. “We will become more deeply engaged here with no way to extricate ourselves,” Eikenberry warned, “short of allowing the country to descend again into lawlessness and chaos.”

McChrystal and his team were blindsided by the cable. “I like Karl, I’ve known him for years, but they’d never said anything like that to us before,” says McChrystal, who adds that he felt “betrayed” by the leak. “Here’s one that covers his flank for the history books. Now if we fail, they can say, ‘I told you so.’ ”

The most striking example of McChrystal’s usurpation of diplomatic policy is his handling of Karzai. It is McChrystal, not diplomats like Eikenberry or Holbrooke, who enjoys the best relationship with the man America is relying on to lead Afghanistan. The doctrine of counterinsurgency requires a credible government, and since Karzai is not considered credible by his own people, McChrystal has worked hard to make him so. Over the past few months, he has accompanied the president on more than 10 trips around the country, standing beside him at political meetings, or shuras, in Kandahar. In February, the day before the doomed offensive in Marja, McChrystal even drove over to the president’s palace to get him to sign off on what would be the largest military operation of the year. Karzai’s staff, however, insisted that the president was sleeping off a cold and could not be disturbed. After several hours of haggling, McChrystal finally enlisted the aid of Afghanistan’s defense minister, who persuaded Karzai’s people to wake the president from his nap.

This is one of the central flaws with McChrystal’s counterinsurgency strategy: The need to build a credible government puts us at the mercy of whatever tin-pot leader we’ve backed – a danger that Eikenberry explicitly warned about in his cable. Even Team McChrystal privately acknowledges that Karzai is a less-than-ideal partner. “He’s been locked up in his palace the past year,” laments one of the general’s top advisers. At times, Karzai himself has actively undermined McChrystal’s desire to put him in charge. During a recent visit to Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Karzai met three U.S. soldiers who had been wounded in Uruzgan province. “General,” he called out to McChrystal, “I didn’t even know we were fighting in Uruzgan!”

Growing up as a military brat, McChrystal exhibited the mixture of brilliance and cockiness that would follow him throughout his career. His father fought in Korea and Vietnam, retiring as a two-star general, and his four brothers all joined the armed services. Moving around to different bases, McChrystal took solace in baseball, a sport in which he made no pretense of hiding his superiority: In Little League, he would call out strikes to the crowd before whipping a fastball down the middle.

McChrystal entered West Point in 1972, when the U.S. military was close to its all-time low in popularity. His class was the last to graduate before the academy started to admit women. The “Prison on the Hudson,” as it was known then, was a potent mix of testosterone, hooliganism and reactionary patriotism. Cadets repeatedly trashed the mess hall in food fights, and birthdays were celebrated with a tradition called “rat fucking,” which often left the birthday boy outside in the snow or mud, covered in shaving cream. “It was pretty out of control,” says Lt. Gen. David Barno, a classmate who went on to serve as the top commander in Afghanistan from 2003 to 2005. The class, filled with what Barno calls “huge talent” and “wild-eyed teenagers with a strong sense of idealism,” also produced Gen. Ray Odierno, the current commander of U.S. forces in Iraq.

The son of a general, McChrystal was also a ringleader of the campus dissidents – a dual role that taught him how to thrive in a rigid, top-down environment while thumbing his nose at authority every chance he got. He accumulated more than 100 hours of demerits for drinking, partying and insubordination – a record that his classmates boasted made him a “century man.” One classmate, who asked not to be named, recalls finding McChrystal passed out in the shower after downing a case of beer he had hidden under the sink. The troublemaking almost got him kicked out, and he spent hours subjected to forced marches in the Area, a paved courtyard where unruly cadets were disciplined. “I’d come visit, and I’d end up spending most of my time in the library, while Stan was in the Area,” recalls Annie, who began dating McChrystal in 1973.

McChrystal wound up ranking 298 out of a class of 855, a serious underachievement for a man widely regarded as brilliant. His most compelling work was extracurricular: As managing editor of The Pointer, the West Point literary magazine, McChrystal wrote seven short stories that eerily foreshadow many of the issues he would confront in his career. In one tale, a fictional officer complains about the difficulty of training foreign troops to fight; in another, a 19-year-old soldier kills a boy he mistakes for a terrorist. In “Brinkman’s Note,” a piece of suspense fiction, the unnamed narrator appears to be trying to stop a plot to assassinate the president. It turns out, however, that the narrator himself is the assassin, and he’s able to infiltrate the White House: “The President strode in smiling. From the right coat pocket of the raincoat I carried, I slowly drew forth my 32-caliber pistol. In Brinkman’s failure, I had succeeded.”

After graduation, 2nd Lt. Stanley McChrystal entered an Army that was all but broken in the wake of Vietnam. “We really felt we were a peacetime generation,” he recalls. “There was the Gulf War, but even that didn’t feel like that big of a deal.” So McChrystal spent his career where the action was: He enrolled in Special Forces school and became a regimental commander of the 3rd Ranger Battalion in 1986. It was a dangerous position, even in peacetime – nearly two dozen Rangers were killed in training accidents during the Eighties. It was also an unorthodox career path: Most soldiers who want to climb the ranks to general don’t go into the Rangers. Displaying a penchant for transforming systems he considers outdated, McChrystal set out to revolutionize the training regime for the Rangers. He introduced mixed martial arts, required every soldier to qualify with night-vision goggles on the rifle range and forced troops to build up their endurance with weekly marches involving heavy backpacks.

In the late 1990s, McChrystal shrewdly improved his inside game, spending a year at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and then at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he co-authored a treatise on the merits and drawbacks of humanitarian interventionism. But as he moved up through the ranks, McChrystal relied on the skills he had learned as a troublemaking kid at West Point: knowing precisely how far he could go in a rigid military hierarchy without getting tossed out. Being a highly intelligent badass, he discovered, could take you far – especially in the political chaos that followed September 11th. “He was very focused,” says Annie. “Even as a young officer he seemed to know what he wanted to do. I don’t think his personality has changed in all these years.”

By some accounts, McChrystal’s career should have been over at least two times by now. As Pentagon spokesman during the invasion of Iraq, the general seemed more like a White House mouthpiece than an up-and-coming commander with a reputation for speaking his mind. When Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld made his infamous “stuff happens” remark during the looting of Baghdad, McChrystal backed him up. A few days later, he echoed the president’s Mission Accomplished gaffe by insisting that major combat operations in Iraq were over. But it was during his next stint – overseeing the military’s most elite units, including the Rangers, Navy Seals and Delta Force – that McChrystal took part in a cover-up that would have destroyed the career of a lesser man.

After Cpl. Pat Tillman, the former-NFL-star-turned-Ranger, was accidentally killed by his own troops in Afghanistan in April 2004, McChrystal took an active role in creating the impression that Tillman had died at the hands of Taliban fighters. He signed off on a falsified recommendation for a Silver Star that suggested Tillman had been killed by enemy fire. (McChrystal would later claim he didn’t read the recommendation closely enough – a strange excuse for a commander known for his laserlike attention to minute details.) A week later, McChrystal sent a memo up the chain of command, specifically warning that President Bush should avoid mentioning the cause of Tillman’s death. “If the circumstances of Corporal Tillman’s death become public,” he wrote, it could cause “public embarrassment” for the president.

“The false narrative, which McChrystal clearly helped construct, diminished Pat’s true actions,” wrote Tillman’s mother, Mary, in her book Boots on the Ground by Dusk. McChrystal got away with it, she added, because he was the “golden boy” of Rumsfeld and Bush, who loved his willingness to get things done, even if it included bending the rules or skipping the chain of command. Nine days after Tillman’s death, McChrystal was promoted to major general.

Two years later, in 2006, McChrystal was tainted by a scandal involving detainee abuse and torture at Camp Nama in Iraq. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, prisoners at the camp were subjected to a now-familiar litany of abuse: stress positions, being dragged naked through the mud. McChrystal was not disciplined in the scandal, even though an interrogator at the camp reported seeing him inspect the prison multiple times. But the experience was so unsettling to McChrystal that he tried to prevent detainee operations from being placed under his command in Afghanistan, viewing them as a “political swamp,” according to a U.S. official. In May 2009, as McChrystal prepared for his confirmation hearings, his staff prepared him for hard questions about Camp Nama and the Tillman cover-up. But the scandals barely made a ripple in Congress, and McChrystal was soon on his way back to Kabul to run the war in Afghanistan.

The media, to a large extent, have also given McChrystal a pass on both controversies. Where Gen. Petraeus is kind of a dweeb, a teacher’s pet with a Ranger’s tab, McChrystal is a snake-eating rebel, a “Jedi” commander, as Newsweek called him. He didn’t care when his teenage son came home with blue hair and a mohawk. He speaks his mind with a candor rare for a high-ranking official. He asks for opinions, and seems genuinely interested in the response. He gets briefings on his iPod and listens to books on tape. He carries a custom-made set of nunchucks in his convoy engraved with his name and four stars, and his itinerary often bears a fresh quote from Bruce Lee. (“There are no limits. There are only plateaus, and you must not stay there, you must go beyond them.”) He went out on dozens of nighttime raids during his time in Iraq, unprecedented for a top commander, and turned up on missions unannounced, with almost no entourage. “The fucking lads love Stan McChrystal,” says a British officer who serves in Kabul. “You’d be out in Somewhere, Iraq, and someone would take a knee beside you, and a corporal would be like ‘Who the fuck is that?’ And it’s fucking Stan McChrystal.”

It doesn’t hurt that McChrystal was also extremely successful as head of the Joint Special Operations Command, the elite forces that carry out the government’s darkest ops. During the Iraq surge, his team killed and captured thousands of insurgents, including Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq. “JSOC was a killing machine,” says Maj. Gen. Mayville, his chief of operations. McChrystal was also open to new ways of killing. He systematically mapped out terrorist networks, targeting specific insurgents and hunting them down – often with the help of cyberfreaks traditionally shunned by the military. “The Boss would find the 24-year-old kid with a nose ring, with some fucking brilliant degree from MIT, sitting in the corner with 16 computer monitors humming,” says a Special Forces commando who worked with McChrystal in Iraq and now serves on his staff in Kabul. “He’d say, ‘Hey – you fucking muscleheads couldn’t find lunch without help. You got to work together with these guys.’ ”

Even in his new role as America’s leading evangelist for counterinsurgency, McChrystal retains the deep-seated instincts of a terrorist hunter. To put pressure on the Taliban, he has upped the number of Special Forces units in Afghanistan from four to 19. “You better be out there hitting four or five targets tonight,” McChrystal will tell a Navy Seal he sees in the hallway at headquarters. Then he’ll add, “I’m going to have to scold you in the morning for it, though.” In fact, the general frequently finds himself apologizing for the disastrous consequences of counterinsurgency. In the first four months of this year, NATO forces killed some 90 civilians, up 76 percent from the same period in 2009 – a record that has created tremendous resentment among the very population that COIN theory is intent on winning over. In February, a Special Forces night raid ended in the deaths of two pregnant Afghan women and allegations of a cover-up, and in April, protests erupted in Kandahar after U.S. forces accidentally shot up a bus, killing five Afghans. “We’ve shot an amazing number of people,” McChrystal recently conceded.

Despite the tragedies and miscues, McChrystal has issued some of the strictest directives to avoid civilian casualties that the U.S. military has ever encountered in a war zone. It’s “insurgent math,” as he calls it – for every innocent person you kill, you create 10 new enemies. He has ordered convoys to curtail their reckless driving, put restrictions on the use of air power and severely limited night raids. He regularly apologizes to Hamid Karzai when civilians are killed, and berates commanders responsible for civilian deaths. “For a while,” says one U.S. official, “the most dangerous place to be in Afghanistan was in front of McChrystal after a ‘civ cas’ incident.” The ISAF command has even discussed ways to make not killing into something you can win an award for: There’s talk of creating a new medal for “courageous restraint,” a buzzword that’s unlikely to gain much traction in the gung-ho culture of the U.S. military.

But however strategic they may be, McChrystal’s new marching orders have caused an intense backlash among his own troops. Being told to hold their fire, soldiers complain, puts them in greater danger. “Bottom line?” says a former Special Forces operator who has spent years in Iraq and Afghanistan. “I would love to kick McChrystal in the nuts. His rules of engagement put soldiers’ lives in even greater danger. Every real soldier will tell you the same thing.”

In March, McChrystal traveled to Combat Outpost JFM – a small encampment on the outskirts of Kandahar – to confront such accusations from the troops directly. It was a typically bold move by the general. Only two days earlier, he had received an e-mail from Israel Arroyo, a 25-year-old staff sergeant who asked McChrystal to go on a mission with his unit. “I am writing because it was said you don’t care about the troops and have made it harder to defend ourselves,” Arroyo wrote.

Within hours, McChrystal responded personally: “I’m saddened by the accusation that I don’t care about soldiers, as it is something I suspect any soldier takes both personally and professionally – at least I do. But I know perceptions depend upon your perspective at the time, and I respect that every soldier’s view is his own.” Then he showed up at Arroyo’s outpost and went on a foot patrol with the troops – not some bullshit photo-op stroll through a market, but a real live operation in a dangerous war zone.

Six weeks later, just before McChrystal returned from Paris, the general received another e-mail from Arroyo. A 23-year-old corporal named Michael Ingram – one of the soldiers McChrystal had gone on patrol with – had been killed by an IED a day earlier. It was the third man the 25-member platoon had lost in a year, and Arroyo was writing to see if the general would attend Ingram’s memorial service. “He started to look up to you,” Arroyo wrote. McChrystal said he would try to make it down to pay his respects as soon as possible.

The night before the general is scheduled to visit Sgt. Arroyo’s platoon for the memorial, I arrive at Combat Outpost JFM to speak with the soldiers he had gone on patrol with. JFM is a small encampment, ringed by high blast walls and guard towers. Almost all of the soldiers here have been on repeated combat tours in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and have seen some of the worst fighting of both wars. But they are especially angered by Ingram’s death. His commanders had repeatedly requested permission to tear down the house where Ingram was killed, noting that it was often used as a combat position by the Taliban. But due to McChrystal’s new restrictions to avoid upsetting civilians, the request had been denied. “These were abandoned houses,” fumes Staff Sgt. Kennith Hicks. “Nobody was coming back to live in them.”

One soldier shows me the list of new regulations the platoon was given. “Patrol only in areas that you are reasonably certain that you will not have to defend yourselves with lethal force,” the laminated card reads. For a soldier who has traveled halfway around the world to fight, that’s like telling a cop he should only patrol in areas where he knows he won’t have to make arrests. “Does that make any fucking sense?” asks Pfc. Jared Pautsch. “We should just drop a fucking bomb on this place. You sit and ask yourself: What are we doing here?”

The rules handed out here are not what McChrystal intended – they’ve been distorted as they passed through the chain of command – but knowing that does nothing to lessen the anger of troops on the ground. “Fuck, when I came over here and heard that McChrystal was in charge, I thought we would get our fucking gun on,” says Hicks, who has served three tours of combat. “I get COIN. I get all that. McChrystal comes here, explains it, it makes sense. But then he goes away on his bird, and by the time his directives get passed down to us through Big Army, they’re all fucked up – either because somebody is trying to cover their ass, or because they just don’t understand it themselves. But we’re fucking losing this thing.”

McChrystal and his team show up the next day. Underneath a tent, the general has a 45-minute discussion with some two dozen soldiers. The atmosphere is tense. “I ask you what’s going on in your world, and I think it’s important for you all to understand the big picture as well,” McChrystal begins. “How’s the company doing? You guys feeling sorry for yourselves? Anybody? Anybody feel like you’re losing?” McChrystal says.

“Sir, some of the guys here, sir, think we’re losing, sir,” says Hicks.

McChrystal nods. “Strength is leading when you just don’t want to lead,” he tells the men. “You’re leading by example. That’s what we do. Particularly when it’s really, really hard, and it hurts inside.” Then he spends 20 minutes talking about counterinsurgency, diagramming his concepts and principles on a whiteboard. He makes COIN seem like common sense, but he’s careful not to bullshit the men. “We are knee-deep in the decisive year,” he tells them. The Taliban, he insists, no longer has the initiative – “but I don’t think we do, either.” It’s similar to the talk he gave in Paris, but it’s not winning any hearts and minds among the soldiers. “This is the philosophical part that works with think tanks,” McChrystal tries to joke. “But it doesn’t get the same reception from infantry companies.”

During the question-and-answer period, the frustration boils over. The soldiers complain about not being allowed to use lethal force, about watching insurgents they detain be freed for lack of evidence. They want to be able to fight – like they did in Iraq, like they had in Afghanistan before McChrystal. “We aren’t putting fear into the Taliban,” one soldier says.

“Winning hearts and minds in COIN is a coldblooded thing,” McChrystal says, citing an oft-repeated maxim that you can’t kill your way out of Afghanistan. “The Russians killed 1 million Afghans, and that didn’t work.”

“I’m not saying go out and kill everybody, sir,” the soldier persists. “You say we’ve stopped the momentum of the insurgency. I don’t believe that’s true in this area. The more we pull back, the more we restrain ourselves, the stronger it’s getting.”

“I agree with you,” McChrystal says. “In this area, we’ve not made progress, probably. You have to show strength here, you have to use fire. What I’m telling you is, fire costs you. What do you want to do? You want to wipe the population out here and resettle it?”

A soldier complains that under the rules, any insurgent who doesn’t have a weapon is immediately assumed to be a civilian. “That’s the way this game is,” McChrystal says. “It’s complex. I can’t just decide: It’s shirts and skins, and we’ll kill all the shirts.”

As the discussion ends, McChrystal seems to sense that he hasn’t succeeded at easing the men’s anger. He makes one last-ditch effort to reach them, acknowledging the death of Cpl. Ingram. “There’s no way I can make that easier,” he tells them. “No way I can pretend it won’t hurt. No way I can tell you not to feel that. . . . I will tell you, you’re doing a great job. Don’t let the frustration get to you.” The session ends with no clapping, and no real resolution. McChrystal may have sold President Obama on counterinsurgency, but many of his own men aren’t buying it.

When it comes to Afghanistan, history is not on McChrystal’s side. The only foreign invader to have any success here was Genghis Khan – and he wasn’t hampered by things like human rights, economic development and press scrutiny. The COIN doctrine, bizarrely, draws inspiration from some of the biggest Western military embarrassments in recent memory: France’s nasty war in Algeria (lost in 1962) and the American misadventure in Vietnam (lost in 1975). McChrystal, like other advocates of COIN, readily acknowledges that counterinsurgency campaigns are inherently messy, expensive and easy to lose. “Even Afghans are confused by Afghanistan,” he says. But even if he somehow manages to succeed, after years of bloody fighting with Afghan kids who pose no threat to the U.S. homeland, the war will do little to shut down Al Qaeda, which has shifted its operations to Pakistan. Dispatching 150,000 troops to build new schools, roads, mosques and water-treatment facilities around Kandahar is like trying to stop the drug war in Mexico by occupying Arkansas and building Baptist churches in Little Rock. “It’s all very cynical, politically,” says Marc Sageman, a former CIA case officer who has extensive experience in the region. “Afghanistan is not in our vital interest – there’s nothing for us there.”

In mid-May, two weeks after visiting the troops in Kandahar, McChrystal travels to the White House for a high-level visit by Hamid Karzai. It is a triumphant moment for the general, one that demonstrates he is very much in command – both in Kabul and in Washington. In the East Room, which is packed with journalists and dignitaries, President Obama sings the praises of Karzai. The two leaders talk about how great their relationship is, about the pain they feel over civilian casualties. They mention the word “progress” 16 times in under an hour. But there is no mention of victory. Still, the session represents the most forceful commitment that Obama has made to McChrystal’s strategy in months. “There is no denying the progress that the Afghan people have made in recent years – in education, in health care and economic development,” the president says. “As I saw in the lights across Kabul when I landed – lights that would not have been visible just a few years earlier.”

It is a disconcerting observation for Obama to make. During the worst years in Iraq, when the Bush administration had no real progress to point to, officials used to offer up the exact same evidence of success. “It was one of our first impressions,” one GOP official said in 2006, after landing in Baghdad at the height of the sectarian violence. “So many lights shining brightly.” So it is to the language of the Iraq War that the Obama administration has turned – talk of progress, of city lights, of metrics like health care and education. Rhetoric that just a few years ago they would have mocked. “They are trying to manipulate perceptions because there is no definition of victory – because victory is not even defined or recognizable,” says Celeste Ward, a senior defense analyst at the RAND Corporation who served as a political adviser to U.S. commanders in Iraq in 2006. “That’s the game we’re in right now. What we need, for strategic purposes, is to create the perception that we didn’t get run off. The facts on the ground are not great, and are not going to become great in the near future.”

But facts on the ground, as history has proven, offer little deterrent to a military determined to stay the course. Even those closest to McChrystal know that the rising anti-war sentiment at home doesn’t begin to reflect how deeply fucked up things are in Afghanistan. “If Americans pulled back and started paying attention to this war, it would become even less popular,” a senior adviser to McChrystal says. Such realism, however, doesn’t prevent advocates of counterinsurgency from dreaming big: Instead of beginning to withdraw troops next year, as Obama promised, the military hopes to ramp up its counterinsurgency campaign even further. “There’s a possibility we could ask for another surge of U.S. forces next summer if we see success here,” a senior military official in Kabul tells me.

Back in Afghanistan, less than a month after the White House meeting with Karzai and all the talk of “progress,” McChrystal is hit by the biggest blow to his vision of counterinsurgency. Since last year, the Pentagon had been planning to launch a major military operation this summer in Kandahar, the country’s second-largest city and the Taliban’s original home base. It was supposed to be a decisive turning point in the war – the primary reason for the troop surge that McChrystal wrested from Obama late last year. But on June 10th, acknowledging that the military still needs to lay more groundwork, the general announced that he is postponing the offensive until the fall. Rather than one big battle, like Fallujah or Ramadi, U.S. troops will implement what McChrystal calls a “rising tide of security.” The Afghan police and army will enter Kandahar to attempt to seize control of neighborhoods, while the U.S. pours $90 million of aid into the city to win over the civilian population.

Even proponents of counterinsurgency are hard-pressed to explain the new plan. “This isn’t a classic operation,” says a U.S. military official. “It’s not going to be Black Hawk Down. There aren’t going to be doors kicked in.” Other U.S. officials insist that doors are going to be kicked in, but that it’s going to be a kinder, gentler offensive than the disaster in Marja. “The Taliban have a jackboot on the city,” says a military official. “We have to remove them, but we have to do it in a way that doesn’t alienate the population.” When Vice President Biden was briefed on the new plan in the Oval Office, insiders say he was shocked to see how much it mirrored the more gradual plan of counterterrorism that he advocated last fall. “This looks like CT-plus!” he said, according to U.S. officials familiar with the meeting.

Whatever the nature of the new plan, the delay underscores the fundamental flaws of counterinsurgency. After nine years of war, the Taliban simply remains too strongly entrenched for the U.S. military to openly attack. The very people that COIN seeks to win over – the Afghan people – do not want us there. Our supposed ally, President Karzai, used his influence to delay the offensive, and the massive influx of aid championed by McChrystal is likely only to make things worse. “Throwing money at the problem exacerbates the problem,” says Andrew Wilder, an expert at Tufts University who has studied the effect of aid in southern Afghanistan. “A tsunami of cash fuels corruption, delegitimizes the government and creates an environment where we’re picking winners and losers” – a process that fuels resentment and hostility among the civilian population. So far, counterinsurgency has succeeded only in creating a never-ending demand for the primary product supplied by the military: perpetual war. There is a reason that President Obama studiously avoids using the word “victory” when he talks about Afghanistan. Winning, it would seem, is not really possible. Not even with Stanley McChrystal in charge.

This article is from the July 8th, 2010 issue of Rolling Stone.

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/the-runaway-general-the-profile-that-brought-down-mcchrystal-192609/

*note: Charles A. Flynn (born c. 1963) is a United States Army general who serves as commanding general of United States Army Pacific since June 4, 2021. He previously served as Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Plans and Training (G3/5/7) of the Army Staff from June 2019 to May 2021. He is the younger brother of Lieutenant General Michael T. Flynn, the 25th United States National Security Advisor, and first to Donald Trump.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_A._Flynn

Read from top.

leadership...

In his second lecture, Thomas E. Ricks explore O.P. Smith... (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rf-KpVgus8)

In the lecture, Ricks does not hold back on General Douglas MacArthur's antics and narcissism...

Oliver Prince Smith (October 26, 1893 – December 25, 1977) was a U.S. Marine four star general and decorated combat veteran of World War II and the Korean War. He is most noted for commanding the 1st Marine Division during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, where he said "Retreat, hell! We're not retreating, we're just advancing in a different direction." He retired at the rank of four-star general, being advanced in rank for having been specially commended for heroism in combat.

Read more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_P._Smith

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>!!!

fear of ourselves...

Mere weeks ago, we did the unthinkable: With thousands of our citizens trapped in Afghanistan, the Biden administration asked the Taliban to extend our deadline for withdrawal.

They said no. We said OK.

The United States of America, capitulating to a medieval death cult.

Our posture on the world stage is exemplified by our increasingly weak president, head in hands and bending before the White House press corps, unable to explain or defend this unmitigated disaster.

No less than the New Yorker, perhaps the most august of left-leaning outlets, asked this week: “Is the U.S. Withdrawal from Afghanistan the End of the American Empire?”

Their conclusion: Not yet, but probably.

You don’t need to be a foreign policy expert to see it. After all, here at home we’re no longer governed by the American DNA — fortitude, confidence, independence of thought — but by Twitter.

And rather than rebel, America lives in fear of it. Get on the wrong side of any issue, utter the wrong word, say or do something offensive and you will be vaporized, canceled, your exile co-signed by cowardly publications, universities, Hollywood studios, multinational corporations.

No longer are we the home of the brave.

The center-left columnist Andrew Sullivan, just last week, told Bill Maher that he did not resign from New York magazine, as announced last year, but was fired with four days’ notice.

Read more: https://nypost.com/2021/09/02/american-dominance-and-values-sorely-tested/

Read from top. The rot started 40 years ago... see: the beginning of the war... It was never going to be a success, unless the USA became demonic... The war in Afghanistan was ill-thought from the beginning by the amateur warriors of the Bush Administration... The army Generals had to make do with a wrong political will that induced the wrong military decisions... So the luck of war was with the Taliban... READ FROM TOP..........

military malcontents...

Open Letter from Retired Generals and Admirals Regarding Afghanistan

The retired Flag Officers signing this letter are calling for the resignation and retirement of the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) based on negligence in performing their duties primarily involving events surrounding the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan. The hasty retreat has left initial estimates at ~15,000 Americans stranded in dangerous areas controlled by a brutal enemy along with ~25,000 Afghan citizens who supported American forces.

What should have happened upon learning of the Commander in Chief’s (President Biden’s) plan to quickly withdraw our forces and close the important power projection base Bagram, without adequate plans and forces in place to conduct the entire operation in an orderly fashion?

As principal military advisors to the CINC/President, the SECDEF and CJCS should have recommended against this dangerous withdrawal in the strongest possible terms. If they did not do everything within their authority to stop the hasty withdrawal, they should resign. Conversely, if they did do everything within their ability to persuade the CINC/President to not hastily exit the country without ensuring the safety of our citizens and Afghans loyal to America, then they should have resigned in protest as a matter of conscience and public statement.

The consequences of this disaster are enormous and will reverberate for decades beginning with the safety of Americans and Afghans who are unable to move safely to evacuation points; therefore, being de facto hostages of the Taliban at this time. The death and torture of Afghans has already begun and will result in a human tragedy of major proportions. The loss of billions of dollars in advanced military equipment and supplies falling into the hands of our enemies is catastrophic. The damage to the reputation of the United States is indescribable. We are now seen, and will be seen for many years, as an unreliable partner in any multinational agreement or operation. Trust in the United States is irreparably damaged.

Moreover, now our adversaries are emboldened to move against America due to the weakness displayed in Afghanistan. China benefits the most followed by Russia, Pakistan, Iran, North Korea and others. Terrorists around the world are emboldened and able to pass freely into our country through our open border with Mexico.

Besides these military operational reasons for resignations, there are leadership, training, and morale reasons for resignations. In interviews, congressional testimony, and public statements it has become clear that top leaders in our military are placing mandatory emphasis on PC “wokeness” related training which is extremely divisive and harmful to unit cohesion, readiness, and war fighting capability. Our military exists to fight and win our Nation’s wars and that must be the sole focus of our top military leaders.

For these reasons we call on the SECDEF Austin and the CJCS General Milley to resign. A fundamental principle in the military is holding those in charge responsible and accountable for their actions or inactions. There must be accountability at all levels for this tragic and avoidable debacle.

Signed

BG Dale F. Andres, USA, (ret) RADM Philip Anselmo, USN, (ret) MG Joe Arbuckle, USA (ret)

BG John C. Arick, USMC (ret)

BG Thomas Lee Ayers, USAF,(ret)

BG Travis Dwight Balch, USAF, (ret) BG Billy A. Barrett, USAF (ret)

BG John A. Bathke, USA,(ret) RADM Jon Bayless, USN, (ret)

BG Charles Bishop, USAF (ret)

BG Don Bolduc, USA (ret)

MG William Bowdon, USMC (ret) VADM Michael Bowman, US N, (ret) LTG William Boykin, USA (ret)

MG Edward Bracken, USAF (ret)

VADM Toney Michael Bucchi, USN (ret) MG Bobby Butcher, USMC (ret)

BG Larry R. Capps, USA (ret)

BG Jim L. Cash, USAF (ret)

LTG James E. Chambers USAF (ret)

MG Carroll D. Childers, USA (ret) RADM Arthur Clark, USN (ret)

VADM Ed Clexton, USN (ret)

MG John J. Closner III, USAF (ret)

BG Richard A. Coleman, USAF, (ret)

BG Peter B. Collins, USMC (ret)

MG David L Commons USAF (ret)

BG Keith B. Connolly USAF (ret)

MG Glenn Curtis, USA, (ret)

MG James I. Dozier, USA (ret)

BG Bob Floyd, USA (ret)

MG Larry Fortmer, USAF (ret)

BG Jerome V. Foust, USA (ret)

BG Jimmy E. Fowler, USA (ret)

RADM J. Fraser, USN (ret)

MG John T. Furlow, USA (ret)

RDML Daniel L. Gard, USN, (ret)

RADM Timothy M. Giardina, USN (ret) MG Francis C. Gideon, USAF (ret)

MG Lee V. Greer, USAF (ret)

BG John H. Grueser, USAF (ret)

MG Ken Hageman, USAF (ret)

BG Milton L. Haines, USAF,(ret)

Gen Alfred Hansen, USAF (ret)

MG Larry Harrington,USA( ret)

MG Bryan G. Hawley, USAF (ret)

MG John W. Hawley, USAF (ret)

BG Norman Ham, USAF (ret)

MG Harold G. Hermès, USAF, (ret) RADM Donald Hickman, USN (ret)

MG William B. Hobgood, USA (ret)

MG Bob Hollingworth, USMC (ret)

MG Jerry D. Holmes, USAF (ret)

BG Blaine D. Holt, USAF (ret.)

BG Paige P. Hunter, USAF (ret)

BG Percy George Hurtado II, USA (ret) MG Dewitt T. Irby, USA (ret)

RADM(L) Grady L. Jackson, USN (ret) RADM Ronny Jackson, USN (ret) ADM. Jerome L. Johnson USN (ret) BG Charles Jones, USAF, (ret)

BG Bob Jordan, USA (ret)

RDML Herbert C. Kaler, USN (ret)

RADM John King, USN (ret)

MG Anthony Kropp USA (ret)

RADM Chuck Kubic, CEC, USN (ret)

RADM Mark L. Leavitt, USN (ret)

BG Douglas E. Lee, USA (ret)

BG Stephen J. Linsenmeyer, USAF (ret) MG James E. Livingston, USMC, MOH (ret) MG John D. Logeman, USAF (ret)

BG Robert W. Lovell, USAF (ret)

MG Jarvis D. Lynch, USMC (ret)

RADM Robert Marsland, USPHS (ret)

BG Charles D. Martin, USAF, (ret)

RADM James I. Maslowski, USN (ret)

MG Keith McCartney, USAF, (ret)

LTG Fred McCorkle, USMC (ret)

LTG Thomas McInerney, USAF (ret)

BG Joel M. McKean, USAF, (ret)

BG Michael P. McRaney, USAF (ret)

BG Joe Mensching, USAF (ret)

MG John F. Miller, USAF (ret)

RADM John A. Moriarty, USN (ret)

RADM David R. Morris, USN (ret)

RADM Bill Newman,USN, (ret)

BG Patricia Nilo, USA (ret)

RADM Michael Stewart O’Bryan, USN (ret) BG Joe Oder, USA, (ret)

MG Ray O’Mara, USAF (ret)

MG Joe S. Owens, USA (ret)

BG John A. Paterson, USAF (ret)

RADM Russ Penniman, USN (ret)

MG Richard Perraut, USAF (ret)

RADM Leonard Picotte, USN (ret)

VADM John Poindexter, USN (ret)

MG David S. Post, USAF (ret)

MG Kevin E. Pottinger, USAF (ret)

RADM J.J. Quinn, USN (ret)

LTG Clifford H. Rees, USAF (ret)

BG Teddy E. Rinebarger, USAF (ret)

MG H. Douglas Robertson, USA (ret)

MG Lee P. Rodgers, USAF, (ret)

BG Neil A. Rohan, USAF, (ret)

MG Donald L. Rutherford, USA, (ret) RADM Norman Saunders, USCG (ret)

MG John P. Schoeppner, Jr., USAF (ret) LTG Hubert G. Smith, USA (ret)

BG Benjamin J. Spraggens, USAF (ret)

MG James Stewart, USAF (ret)

RADM Jeremy D. Taylor, USN (ret)

LTG William Thurman, USAF (ret)

BG Robert Titus, USAF (ret)

LTG Lansford E. Trapp Jr, USAF (ret)

BG George W. Treadwell, USA(ret)

MG John M. Urias, USA (ret)

BG Richard J. Valente, USA (ret)

MG Paul Vallely, USA (ret)

BG William L. Welch, USAF (ret)

MG Kenneth W. Weir, USMCR (ret)

BG William Herbert Weir, USA (ret)

BG William Weiss,USMC, (ret)

RADM David Weitzman, MD USCG (ret) BG William L. Welsh, USAF (ret)

MG Mike Wiedemer, USAF (ret)

MG Richard O. Wightman, Jr. USA (ret) MG Joseph Benson Wilson, USAF (ret) BG Robert E. Windham, USA (ret) RADM Denny Wisely, USN (ret)

BG Robert V. Woods, USAF (ret)

HIDDEN link available...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.

post-mortem of chaos...

BY Salman Rafi Sheikh

The chaos we have seen in Afghanistan following the Taliban takeover and the American rush to evacuate its diplomatic staff and other personnel signifies the US failure at multiple levels. On the one hand, the Taliban takeover within days of the US withdrawal was/is an intelligence failure. In May, a US intelligence report had predicted that it will take the Taliban at least six months to capture Kabul. In July, Biden was up-beat that the Afghanistan will not be America’s another “Saigon moment.” “There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of an embassy of the United States in Afghanistan”, stressed Biden last month. According to one former US military official, the Taliban takeover is “an intelligence failure of the highest order”, one that will have major repercussions for the US in the future, especially at a time when Washington is doing its best to redefine its ties across Southeast Asia as a security and military bulwark to counter China. In Europe, it could push European states – in particular, Germany and France – to think more deeply about developing a security infrastructure and a foreign policy completely independent of the US.

The Afghanistan debacle is, therefore, going to leave a major impact on the future of the US standing in the world. Regardless of whether the US officials acknowledge this or not, the magnanimity of the failure is enormous. Washington’s refusal to acknowledge failure notwithstanding, the August 2021 report of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction has shown how and why the US failed in Afghanistan on all fronts, including strategy, planning, execution and oversight. The report draws major conclusions that speak volumes about the US (in)ability to lead. Some of the conclusions that the report draws include:

The failure happened despite the fact that, as Biden recently boasted off,

“America has sent its finest young men and women, invested nearly $1 trillion dollars, trained over 300,000 Afghan soldiers and police, equipped them with state-of-the-art military equipment, and maintained their air force as part of the longest war in US history,”