Search

Recent comments

- epstein class....

45 min 46 sec ago - in writing....

57 min 17 sec ago - hoped....

2 hours 57 min ago - murdering kids....

3 hours 57 min ago - saving....

4 hours 26 min ago - a speech never made....

17 hours 57 min ago - wardonald...

19 hours 30 min ago - MAGA fools

1 day 4 hours ago - the ugliest excuse to go to war.....

1 day 15 hours ago - morons....

1 day 16 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

losers and losers…...

In Washington, wide agreement exists that the Russian army’s performance in the Kremlin’s ongoing Ukraine “special military operation” ranks somewhere between lousy and truly abysmal. The question is: Why? The answer in American policy circles, both civilian and military, appears all but self-evident. Vladimir Putin’s Russia has stubbornly insisted on ignoring the principles, practices, and methods identified as necessary for success in war and perfected in this century by the armed forces of the United States. Put simply, by refusing to do things the American way, the Russians are failing badly against a far weaker foe.

Russia’s Underperforming Military (and Ours)Convenient Lessons to Impede Learning

BY ANDREW BACEVICH

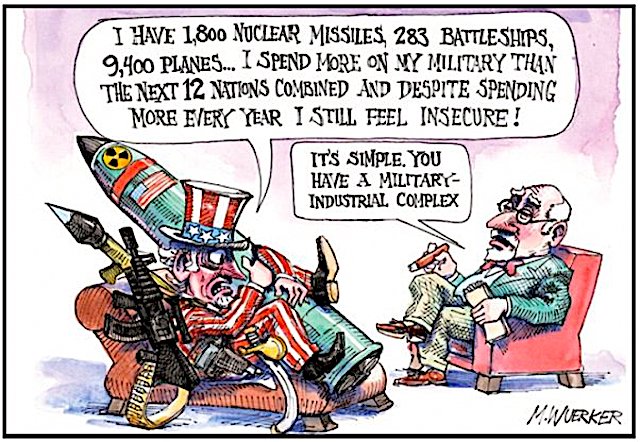

Granted, American analysts — especially the retired military officers who opine on national news shows — concede that other factors have contributed to Russia’s sorry predicament. Yes, heroic Ukrainian resistance, reminiscent of the Winter War of 1939-1940 when Finland tenaciously defended itself against the Soviet Union’s more powerful military, caught the Russians by surprise. Expectations that Ukrainians would stand by while the invaders swept across their country proved wildly misplaced. In addition, comprehensive economic sanctions imposed by the West in response to the invasion have complicated the Russian war effort. By no means least of all, the flood of modern weaponry provided by the United States and its allies — God bless the military-industrial-congressional complex — have appreciably enhanced Ukrainian fighting power.

Still, in the view of American military figures, all of those factors take a backseat to Russia’s manifest inability (or refusal) to grasp the basic prerequisites of modern warfare. The fact that Western observers possess a limited understanding of how that country’s military leadership functions makes it all the easier to render such definitive judgments. It’s like speculating about Donald Trump’s innermost convictions. Since nobody really knows, any forcefully expressed opinion acquires at least passing credibility.

The prevailing self-referential American explanation for Russian military ineptitude emphasizes at least four key points:

* First, the Russians don’t understand jointness, the military doctrine that provides for the seamless integration of ground, air, and maritime operations, not only on Planet Earth but in cyberspace and outer space;

* Second, Russia’s land forces haven’t adhered to the principles of combined arms warfare, first perfected by the Germans in World War II, that emphasizes the close tactical collaboration of tanks, infantry, and artillery;

* Third, Russia’s longstanding tradition of top-down leadership inhibits flexibility at the front, leaving junior officers and noncommissioned officers to relay orders from on high without demonstrating any capacity to, or instinct for, exercising initiative on their own;

* Finally, the Russians appear to lack even the most rudimentary understanding of battlefield logistics — the mechanisms that provide a steady and reliable supply of the fuel, food, munitions, medical support, and spare parts needed to sustain a campaign.

Implicit in this critique, voiced by self-proclaimed American experts, is the suggestion that, if the Russian army had paid more attention to how U.S. forces deal with such matters, they would have fared better in Ukraine. That they don’t — and perhaps can’t — comes as good news for Russia’s enemies, of course. By implication, Russian military ineptitude obliquely affirms the military mastery of the United States. We define the standard of excellence to which others can only aspire.

Reducing War to a Formula

All of which begs a larger question the national security establishment remains steadfastly oblivious to: If jointness, combined arms tactics, flexible leadership, and responsive logistics hold the keys to victory, why haven’t American forces — supposedly possessing such qualities in abundance — been able to win their own equivalents of the Ukraine War? After all, Russia has only been stuck in Ukraine for six months, while the U.S. was stuck in Afghanistan for 20 years and still has troops in Iraq almost two decades after its disastrous invasion of that country.

To rephrase the question: Why does explaining the Russian underperformance in Ukraine attract so much smug commentary here, while American military underperformance gets written off?

Perhaps written off is too harsh. After all, when the U.S. military fails to meet expectations, there are always some who will hasten to point the finger at civilian leaders for screwing up. Certainly, this was the case with the chaotic U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. Critics were quick to pin the blame on President Biden for that debacle, while the commanders who had presided over the war there for those 20 years escaped largely unscathed. Indeed, some of those former commanders like retired general and ex-CIA Director David Petraeus, aka “King David,” were eagerly sought after by the media as Kabul fell.

So, if the U.S. military performance since the Global War on Terror was launched more than two decades ago rates as, to put it politely, a disappointment — and that would be my view — it might be tempting to lay responsibility at the feet of the four presidents, eight secretaries of defense (including two former four-star generals), and the various deputy secretaries, undersecretaries, assistant secretaries, and ambassadors who designed and implemented American policy in those years. In essence, this becomes an argument for sustained generational incompetence.

There’s a flipside to that argument, however. It would tag the parade of generals who presided over the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (and lesser conflicts like those in Libya, Somalia, and Syria) as uniformly not up to the job — another argument for generational incompetence. Members of the once-dominant Petraeus fan club might cite him as a notable exception. Yet, with the passage of time, King David’s achievements as general-in-chief first in Baghdad and then in Kabul have lost much of their luster. The late “Stormin’ Norman” Schwarzkopf and General Tommy Franks, their own “victories” diminished by subsequent events, might sympathize.

Allow me to suggest another explanation, however, for the performance gap that afflicts the twenty-first-century U.S. military establishment. The real problem hasn’t been arrogant, ill-informed civilians or generals who lack the right stuff or suffer from bad luck. It’s the way Americans, especially those wielding influence in national security circles, including journalists, think tankers, lobbyists, corporate officials in the military-industrial complex, and members of Congress, have come to think of war as an attractive, affordable means of solving problems.

Military theorists have long emphasized that by its very nature, war is fluid, elusive, capricious, and permeated with chance and uncertainty. Practitioners tend to respond by suggesting that, though true, such descriptions are not helpful. They prefer to conceive of war as essentially knowable, predictable, and eminently useful — the Swiss Army knife of international politics.

Hence, the tendency, among both civilian and military officials in Washington, not to mention journalists and policy intellectuals, to reduce war to a phrase or formula (or better yet to a set of acronyms), so that the entire subject can be summarized in a slick 30-minute slide presentation. That urge to simplify — to boil things down to their essence — is anything but incidental. In Washington, the avoidance of complexity and ambiguity facilitates marketing (that is, shaking down Congress for money).

To cite one small example of this, consider a recent military document “Army Readiness and Modernization in 2022,” produced by propagandists at the Association of the United States Army, which purports to describe where the U.S. Army is headed. It identifies “eight cross-functional teams” meant to focus on “six priorities.” If properly resourced and vigorously pursued, these teams and priorities will ensure, it claims, that “the army maintains all-domain overmatch against all adversaries in future fights.”

Set aside the uncomfortable fact that, when it counted last year in Kabul, American forces demonstrated anything but all-domain overmatch. Still, what the Army’s leadership aims to do between now and 2035 is create “a transformed multi-domain army” by fielding a plethora of new systems, described in a blizzard of acronyms: ERCA, PrSM, LRHW, OMVF, MPF, RCV, AMPV, FVL, FLRAA, FARA, BLADE, CROWS, MMHEL, and so on, more or less ad infinitum.

Perhaps you won’t be surprised to learn that the Army’s plan, or rather vision, for its future avoids the slightest mention of costs. Nor does it consider potential complications — adversaries equipped with nuclear weapons, for example — that might interfere with its aspirations to all-domain overmatch.

Yet the document deserves our attention as an exquisite example of Pentagon-think. It provides the Army’s preferred answer to a question of nearly existential importance — not “How can the Army help keep Americans safe?” but “How can the Army maintain, and ideally increase, its budget?”

Hidden inside that question is an implicit assumption that sustaining even the pretense of keeping Americans safe requires a military of global reach that maintains a massive global presence. Given the spectacular findings of the James Webb Telescope, perhaps galactic will one day replace global in the Pentagon’s lexicon. In the meantime, while maintaining perhaps 750 military bases on every continent except Antarctica, that military rejects out of hand the proposition that defending Americans where they live — that is, within the boundaries of the 50 states comprising the United States — can suffice to define its overarching purpose.

And here we arrive at the crux of the matter: militarized globalism, the Pentagon’s preferred paradigm for basic policy, has become increasingly unaffordable. With the passage of time, it’s also become beside the point. Americans simply don’t have the wallet to satisfy budgetary claims concocted in the Pentagon, especially those that ignore the most elemental concerns we face, including disease, drought, fire, floods, and sea-level rise, not to mention averting the potential collapse of our constitutional order. All-domain overmatch is of doubtful relevance to such threats.

To provide for the safety and well-being of our republic, we don’t need further enhancements to jointness, combined arms tactics, flexible leadership, and responsive logistics. Instead, we need an entirely different approach to national security.

Come Home, America, Before It’s Too Late

Given the precarious state of American democracy, aptly described by President Biden in his recent address in Philadelphia, our most pressing priority is repairing the damage to our domestic political fabric, not engaging in another round of “great power competition” dreamed up by fevered minds in Washington. Put simply, the Constitution is more important than the fate of Taiwan.

I apologize: I know that I have blasphemed. But the times suggest that we weigh the pros and cons of blasphemy. With serious people publicly warning about the possible approach of civil war and many of our far-too-well armed fellow citizens welcoming the prospect, perhaps the moment has come to reconsider the taken-for-granted premises that have sustained U.S. national security policy since the immediate aftermath of World War II.

More blasphemy! Did I just advocate a policy of isolationism?

Heaven forfend! What I would settle for instead is a modicum of modesty and prudence, along with a lively respect for (rather than infatuation with) war.

Here is the unacknowledged bind in which the Pentagon has placed itself — and the rest of us: by gearing up to fight (however ineffectively) anywhere against any foe in any kind of conflict, it finds itself prepared to fight nowhere in particular. Hence, the urge to extemporize on the fly, as has been the pattern in every conflict of ours since the Vietnam War. On occasion, things work out, as in the long-forgotten, essentially meaningless 1983 invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada. More often than not, however, they don’t, no matter how vigorously our generals and our troops apply the principles of jointness, combined arms, leadership, and logistics.

Americans spend a lot of time these days trying to figure out what makes Vladimir Putin tick. I don’t pretend to know, nor do I really much care. I would say this, however: Putin’s plunge into Ukraine confirms that he learned nothing from the folly of post-9/11 U.S. military policy.

Will we, in our turn, learn anything from Putin’s folly? Don’t count on it.

Andrew Bacevich

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.

Andrew Bacevich, a TomDispatch regular, is president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. His latest book, co-edited with Danny Sjursen, is Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Misguided Wars. In November, his new Dispatch book, On Shedding an Obsolete Past: Bidding Farewell to the American Century, will be published.

READ MORE:

https://tomdispatch.com/russias-underperforming-military-and-ours/

GUSNOTE: THE RUSSIANS DECIDED ON A MINIMALIST APPROACH: SAY 125,000 RUSSIAN TROOPS VERSUS 700,000 UKRAINIANS HELPED BY THE MIGHT OF THE US/UK/EU/NATO WEAPONRY, INTELLIGENCE AND TACTICS. IN THIS REGARD, THE RUSSIANS CHOSE TO RESTRICT THEIR TARGETS TO MILITARY INSTALLATIONS AND HARDWARE. CIVILIANS KILLED HAVE OFTEN BEEN DUE TO UKRAINIAN FIRE. THE RUSSIAN FORAY ONTO KIEV WAS HALF AND HALF A THREAT AND A DIVERSION. AS PUTIN SAYS, "THEY (THE RUSSIANS) ARE NOT IN A HURRY". THE ATTACK BY THE UKRAINIAN ARMY IN KARKIV (NOT A SURPRISE FOR THE RUSSIANS WHO WERE READY TO RETREAT KNOWING THEY WERE UNDER-STRENGTH AND THE CANDLE WAS NOT WORTH THE WICK SO TO SPEAK). YET THE RUSSIANS WERE ABLE TO INFLICT A LOT OF DAMAGE TO THE UKRAINIANS AND THEIR MILITARY ASSETS.

OF COURSE THE MENTION OF MASS GRAVES AND RUSSIAN WAR CRIMES ALWAYS COME UP WITH LITTLE SHIT ZELENSKY. IT'S FOR DISPLAY LIKE A PEACOCK IN A PEAR-SHAPED TREE. IT'S ANOTHER FALSE FLAG THAT THE WESTERN MEDIA LOVE LIKE ICE-CREAM...

PUTIN HAS WARNED LITTLE ZELENSKY THAT IF HIS TROOPS CONTINUE TO KILL A FEW CIVILIANS IN RUSSIA AND THE DONBASS, THE RUSSIANS WILL RETALIATE WITH MIGHT. RUSSIA STILL HOLDS ABOUT 120,000 sq km OF THE DONBASS.

BE PREPARED. THE RUSSIAN MILITARY IS NOT AS BRASH AS THE US's BUT FAR MORE EFFICIENT (AS SHOWN IN SYRIA).

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 17 Sep 2022 - 7:32pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

kaput general Volt followed by general moroz…...

The Kharkov Game-Changer PEPE ESCOBARWars are not won by psyops. Ask Nazi Germany. Still, it’s been a howler to watch NATOstan media on Kharkov, gloating in unison about “the hammer blow that knocks out Putin”, “the Russians are in trouble”, and assorted inanities.

Facts: Russian forces withdrew from the territory of Kharkov to the left bank of the Oskol river, where they are now entrenched. A Kharkov-Donetsk-Lugansk line seems to be stable. Krasny Liman is threatened, besieged by superior Ukrainian forces, but not lethally.

No one – not even Maria Zakharova, the contemporary female equivalent of Hermes, the messenger of the Gods – knows what the Russian General Staff (RGS) plans, in this case and all others. If they say they do, they are lying.

As it stands, what may be inferred with a reasonable degree of certainty is that a line – Svyatogorsk-Krasny Liman-Yampol-Belogorovka – can hold out long enough with their current garrisons until fresh Russian forces are able to swoop in and force the Ukrainians back beyond the Seversky Donets line.

All hell broke loose – virtually – on why Kharkov happened. The people’s republics and Russia never had enough men to defend a 1,000 km-long frontline. NATO’s entire intel capabilities noticed – and profited from it.

There were no Russian Armed Forces in those settlements: only Rosgvardia, and these are not trained to fight military forces. Kiev attacked with an advantage of around 5 to 1. The allied forces retreated to avoid encirclement. There are no Russian troop losses because there were no Russian troops in the region.

Arguably this may have been a one-off. The NATO-run Kiev forces simply can’t do a replay anywhere in Donbass, or in Kherson, or in Mariupol. These are all protected by strong, regular Russian Army units.

It’s practically a given that if the Ukrainians remain around Kharkov and Izyum they will be pulverized by massive Russian artillery. Military analyst Konstantin Sivkov maintains that, “most combat-ready formations of the Armed Forces of Ukraine are now being grounded (…) we managed to lure them into the open and are now systematically destroying them.”

The NATO-run Ukrainian forces, crammed with NATO mercenaries, had spent 6 months hoarding equipment and reserving trained assets exactly for this Kharkov moment – while dispatching disposables into a massive meat grinder. It will be very hard to sustain an assembly line of substantial prime assets to pull off something similar again.

The next days will show whether Kharkov and Izyum are connected to a much larger NATO push. The mood in NATO-controlled EU is approaching Desperation Row. There’s a strong possibility this counter-offensive signifies NATO entering the war for good, while displaying quite tenuous plausible deniability: their veil of – fake – secrecy cannot disguise the presence of “advisers” and mercenaries all across the spectrum.

Decommunization as de-energization

The Special Military Operation (SMO), conceptually, is not about conquering territory per se: it is, or it was, so far, about protection of Russophone citizens in occupied territories, thus demilitarization cum denazification.

That concept may be about to be tweaked. And that’s where the tortuous, tricky debate on Russia mobilization fits in. Yet even a partial mobilization may not be necessary: what’s needed are reserves to properly allow allied forces to cover rear/defensive lines. Hardcore fighters of the Kadyrov contingent kind would continue to play offense.

It’s undeniable that Russian troops lost a strategically important node in Izyum. Without it, the complete liberation of Donbass becomes significantly harder.

Yet for the collective West, whose carcass slouches inside a vast simulacra bubble, it’s the pysops that matters much more than a minor military advance: thus all that gloating on Ukraine being able to drive the Russians out of the whole of Kharkov in only four days – while they had 6 months to liberate Donbass, and didn’t.

So, across the West, the reigning perception – frantically fomented by psyops experts – is that the Russian military were hit by that “hammer blow” and will hardly recover.

Kharkov was preciously timed – as General Winter is around the corner; the Ukraine issue was already suffering from public opinion fatigue; and the propaganda machine needed a boost to turbo-lubricate the multi-billion dollar weaponizing rat line.

Yet Kharkov may have forced Moscow’s hand to increase the pain dial. That came via a few well-placed Mr. Kinzhals leaving the Black Sea and the Caspian to present their business cards to the largest thermal power plants in northeast and central Ukraine (most of the energy infrastructure is in the southeast).

Half of Ukraine suddenly lost power and water. Trains came to a halt. If Moscow decides to take out all major Ukraine substations at once, all it takes is a few missiles to totally smash the Ukrainian energy grid – adding a new meaning to “decommunization”: de-energization.

According to an expert analysis, “if transformers of 110-330 kV are damaged, then it will almost never be possible to put it into operation (…) And if this happens at least at 5 substations at the same time, then everything is kaput. Stone age forever.”

Russian government official Marat Bashirov was way more colorful: “Ukraine is being plunged into the 19th century. If there is no energy system, there will be no Ukrainian army. The matter of fact is that General Volt came to the war, followed by General Moroz (“frost”).

And that’s how we might be finally entering “real war” territory – as in Putin’s notorious quip that “we haven’t even started anything yet.”

A definitive response will come from the RSG in the next few days.

Once again, a fiery debate rages on what Russia will do next (the RGS, after all, is inscrutable, except for Yoda Patrushev).

The RGS may opt for a serious strategic strike of the decapitating kind elsewhere – as in changing the subject for the worse (for NATO).

It may opt for sending more troops to protect the front line (without partial mobilization).

And most of all it may enlarge the SMO mandate – going to total destruction of Ukrainian transport/energy infrastructure, from gas fields to thermal power plants, substations, and shutting down nuclear power plants.

Well, it could always be a mix of all of the above: a Russian version of Shock and Awe – generating an unprecedented socio-economic catastrophe. That has already been telegraphed by Moscow: we can revert you to the Stone Age at any time and in a matter of hours(italics mine). Your cities will greet General Winter with zero heating, freezing water, power outages and no connectivity.

A counter-terrorist operation

All eyes are on whether “centers of decision” – as in Kiev – may soon get a Kinzhal visit. This would signify Moscow has had enough. The siloviki certainly did. But we’re not there – yet. Because for an eminently diplomatic Putin the real game revolves around those gas supplies to the EU, that puny plaything of American foreign policy.

Putin is certainly aware that the internal front is under some pressure. He refuses even partial mobilization. A perfect indicator of what may happen in winter is the referenda in liberated territories. The limit date is November 4 – the Day of National Unity, a commemoration introduced in 2004 to replace the celebration of the October revolution.

With the accession of these territories to Russia, any Ukrainian counter-offensive would qualify as an act of war against regions incorporated into the Russian Federation. Everyone knows what that means.

It may now be painfully obvious that when the collective West is waging war – hybrid and kinetic, with everything from massive intel to satellite data and hordes of mercenaries – against you, and you insist on conducting a hazily-defined Special Military Operation (SMO), you may be up for some nasty surprises.

So the SMO status may be about to change: it’s bound to become a counter-terrorist operation.

This is an existential war. A do or die affair. The American geopolitical /geoeconomic goal, to put it bluntly, is to destroy Russian unity, impose regime change and plunder all those immense natural resources. Ukrainians are nothing but cannon fodder: in a sort of twisted History remake, the modern equivalents of the pyramid of skulls Timur cemented into 120 towers when he razed Baghdad in 1401.

If may take a “hammer blow” for the RSG to wake up. Sooner rather than later, gloves – velvet and otherwise – will be off. Exit SMO. Enter War.

READ MORE:

https://www.unz.com/pescobar/the-kharkov-game-changer/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.....

no honor nor integrity at the top….

William Astore, Something Is Rotten in the U.S. Military

POSTED ON SEPTEMBER 29, 2022

Here’s the curious thing: since at least the Vietnam War era of the 1960s and early 1970s, the United States has been almost continuously at war. Certain of those conflicts like the Vietnam War itself and those in Iraq and Afghanistan in this century are still remembered by many of us. Honestly, though, who remembers Grenada or Panama or the first Gulf War or even the struggle against ISIS, the endless (still ongoing) bombing of Somalia, and this country’s military adventures in Libya, Yemen, and elsewhere across the Greater Middle East and Northern Africa? And doubtless, I’m forgetting some conflicts myself. Oh, yes, what about the 1999 bombing of Serbia? So it goes, or at least has gone, for more than half a century.

As Stan Cox pointed out at TomDispatch recently, the U.S. military, as the largest institutional user of petroleum in the world today, now seems at war not just with other countries or terror movements of various sorts, but with the planet itself. And don’t forget those 750 bases our military occupies on every continent except Antarctica or the staggering Pentagon and national security budgets that have continued to fund all of the above (and so little else).

Russia has indeed invaded Ukraine, causing a harrowing nightmare all too near the heart of Europe. And China has indeed been dispatching warships, drones, and missiles menacingly close to Taiwan. Still, when it comes to militarizing the planet in these last decades, nothing compares to our own military. And looking back — as retired Air Force lieutenant colonel, historian, and TomDispatch regular William Astore, who also runs the Bracing Views blog, does today — tell me that it truly isn’t the story from hell.

Astore mentions a phrase that no one who lived through the Vietnam years is ever likely to forget: “the light at the end of the tunnel.” Even the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam used it about a conflict in which only darkness lay at the end of that very “tunnel.” As an image, it was, of course, supposed to offer hope in a war that seemed, like enough of our conflicts in the years that followed, to be going anything but our way. And these days, with such conflicts seemingly heading home in some bizarre fashion, who could doubt that, metaphorically speaking, all of us now find ourselves in some version of that same tunnel — with the light at its end perhaps the flames of an overheating planet. And with that in mind, let Astore explore the nature of the military that so many of your tax dollars have gone to support in these years. And then, be depressed, very depressed. Tom

Integrity Optional

Lies and Dishonor Plague America's War Machine

BY WILLIAM J. ASTORE

As a military professor for six years at the U.S. Air Force Academy in the 1990s, I often walked past the honor code prominently displayed for all cadets to see. Its message was simple and clear: they were not to tolerate lying, cheating, stealing, or similar dishonorable acts. Yet that’s exactly what the U.S. military and many of America’s senior civilian leaders have been doing from the Vietnam War era to this very day: lying and cooking the books, while cheating and stealing from the American people. And yet the most remarkable thing may be that no honor code turns out to apply to them, so they’ve suffered no consequences for their mendacity and malfeasance.Where’s the “honor” in that?

It may surprise you to learn that “integrity first” is the primary core value of my former service, the U.S. Air Force. Considering the revelations of the Pentagon Papers, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg in 1971; the Afghan War papers, first revealed by the Washington Post in 2019; and the lack of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, among other evidence of the lying and deception that led to the invasion and occupation of that country, you’ll excuse me for assuming that, for decades now when it comes to war, “integrity optional” has been the true core value of our senior military leaders and top government officials.

As a retired Air Force officer, let me tell you this: honor code or not, you can’t win a war with lies — America proved that in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq — nor can you build an honorable military with them. How could our high command not have reached such a conclusion themselves after all this time?

So Many Defeats, So Little Honesty

Like many other institutions, the U.S. military carries with it the seeds of its own destruction. After all, despite being funded in a fashion beyond compare and spreading its peculiar brand of destruction around the globe, its system of war hasn’t triumphed in a significant conflict since World War II (with the war in Korea remaining, almost three-quarters of a century later, in a painful and festering stalemate). Even the ending of the Cold War, allegedly won when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, only led to further wanton military adventurism and, finally, defeat at an unsustainable cost — more than $8 trillion — in Washington’s ill-fated Global War on Terror. And yet, years later, that military still has a stranglehold on the national budget.

So many defeats, so little honesty: that’s the catchphrase I’d use to characterize this country’s military record since 1945. Keeping the money flowing and the wars going proved far more important than integrity or, certainly, the truth. Yet when you sacrifice integrity and the truth in the cause of concealing defeat, you lose much more than a war or two. You lose honor — in the long run, an unsustainable price for any military to pay.

Or rather it should be unsustainable, yet the American people have continued to “support” their military, both by funding it astronomically and expressing seemingly eternal confidence in it — though, after all these years, trust in the military has dipped somewhat recently. Still, in all this time, no one in the senior ranks, civilian or military, has ever truly been called to account for losing wars prolonged by self-serving lies. In fact, too many of our losing generals have gone right through that infamous “revolving door” into the industrial part of the military-industrial complex — only to sometimes return to take top government positions.

Our military has, in fact, developed a narrative that’s proven remarkably effective in insulating it from accountability. It goes something like this: U.S. troops fought hard in [put the name of the country here], so don’t blame us. Indeed, you must support us, especially given all the casualties of our wars. They and the generals did their best, under the usual political constraints. On occasion, mistakes were made, but the military and the government had good and honorable intentions in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere.

Besides, were you there, Charlie? If you weren’t, then STFU, as the acronym goes, and be grateful for the security you take for granted, earned by America’s heroes while you were sitting on your fat ass safe at home.

It’s a narrative I’ve heard time and time again and it’s proven persuasive, partially because it requires the rest of us, in a conscription-free country, to do nothing and think nothing about that. Ignorance is strength, after all.

War Is Brutal

The reality of it all, however, is so much harsher than that. Senior military leaders have performed poorly. War crimes have been covered up. Wars fought in the name of helping others have produced horrendous civilian casualties and stunning numbers of refugees. Even as those wars were being lost, what President Dwight D. Eisenhowerfirst labeled the military-industrial complex has enjoyed windfall profits and expanding power. Again, there’s been no accountability for failure. In fact, only whistleblowing truth-tellers like Chelsea Manning and Daniel Hale have been punished and jailed.

Ready for an even harsher reality? America is a nation being unmade by war, the very opposite of what most Americans are taught. Allow me to explain. As a country, we typically celebrate the lofty ideals and brave citizen-soldiers of the American Revolution. We similarly celebrate the Second American Revolution, otherwise known as the Civil War, for the elimination of slavery and reunification of the country; after which, we celebrate World War II, including the rise of the Greatest Generation, America as the arsenal of democracy, and our emergence as the global superpower.

By celebrating those three wars and essentially ignoring much of the rest of our history, we tend to view war itself as a positive and creative act. We see it as making America, as part of our unique exceptionalism. Not surprisingly, then, militarism in this country is impossible to imagine. We tend to see ourselves, in fact, as uniquely immune to it, even as war and military expenditures have come to dominate our foreign policy, bleeding into domestic policy as well.

If we as Americans continue to imagine war as a creative, positive, essential part of who we are, we’ll also continue to pursue it. Or rather, if we continue to lie to ourselves about war, it will persist.

It’s time for us to begin seeing it not as our making but our unmaking, potentially even our breaking — as democracy’s undoing as well as the brutal thing it truly is.

A retired U.S. military officer, educated by the system, I freely admit to having shared some of its flaws. When I was an Air Force engineer, for instance, I focused more on analysis and quantification than on synthesis and qualification. Reducing everything to numbers, I realize now, helps provide an illusion of clarity, even mastery. It becomes another form of lying, encouraging us to meddle in things we don’t understand.

This was certainly true of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, his “whiz kids,” and General William Westmoreland during the Vietnam War; nor had much changed when it came to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and General David Petraeus, among others, in the Afghan and Iraq War years. In both eras, our military leaders wielded metrics and swore they were winning even as those wars circled the drain.

And worse yet, they were never held accountable for those disasters or the blunders and lies that went with them (though the antiwar movement of the Vietnam era certainly tried). All these years later, with the Pentagon still ascendant in Washington, it should be obvious that something has truly gone rotten in our system.

Here’s the rub: as the military and one administration after another lied to the American people about those wars, they also lied to themselves, even though such conflicts produced plenty of internal “papers” that raised serious concerns about lack of progress. Robert McNamara typically knew that the situation in Vietnam was dire and the war essentially unwinnable. Yet he continued to issue rosy public reports of progress, while calling for more troops to pursue that illusive “light at the end of the tunnel.” Similarly, the Afghan War papers released by the Washington Post show that senior military and civilian leaders realized that war, too, was going poorly almost from the beginning, yet they reported the very opposite to the American people. So many corners were being “turned,” so much “progress” being made in official reports even as the military was building its own rhetorical coffin in that Afghan graveyard of empires.

Too bad wars aren’t won by “spin.” If they were, the U.S. military would be undefeated.

Two Books to Help Us See the Lies

Two recent books help us see that spin for what it was. In Because Our Fathers Lied, Craig McNamara, Robert’s son, reflects on his father’s dishonesty about the Vietnam War and the reasons for it. Loyalty was perhaps the lead one, he writes. McNamara suppressed his own serious misgivings out of misplaced loyalty to two presidents, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, while simultaneously preserving his own position of power in the government.

Robert McNamara would, in fact, later pen his own mea culpa, admitting how “terribly wrong” he’d been in urging the prosecution of that war. Yet Craig finds his father’s late confession of regret significantly less than forthright and fully honest. Robert McNamara fell back on historical ignorance about Vietnam as the key contributing factor in his unwise decision-making, but his son is blunt in accusing his dad of unalloyed dishonesty. Hence the title of his book, citing Rudyard Kipling’s pained confession of his own complicity in sending his son to die in the trenches of World War I: “If any question why we died/Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

The second book is Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Misguided Wars, edited by Andrew Bacevich and Danny Sjursen. In my view, the word “misguided” doesn’t quite capture the book’s powerful essence, since it gathers 15 remarkable essays by Americans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq and witnessed the patent dishonesty and folly of those wars. None dare speak of failure might be a subtheme of these essays, as initially highly motivated and well-trained troops became disillusioned by wars that went nowhere, even as their comrades often paid the ultimate price, being horribly wounded or dying in those conflicts driven by lies.

This is more than a work of dissent by disillusioned troops, however. It’s a call for the rest of us to act. Dissent, as West Point graduate and Army Captain Erik Edstrom reminds us, “is nothing short of a moral obligation” when immoral wars are driven by systemic dishonesty. Army Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Davis, who blew an early whistle on how poorly the Afghan War was going, writes of his “seething” anger “at the absurdity and unconcern for the lives of my fellow soldiers displayed by so many” of the Army’s senior leaders.

Former Marine Matthew Hoh, who resigned from the State Department in opposition to the Afghan “surge” ordered by President Barack Obama, speaks movingly of his own “guilt, regret, and shame” at having served in Afghanistan as a troop commander and wonders whether he can ever atone for it. Like Craig McNamara, Hoh warns of the dangers of misplaced loyalty. He remembers telling himself that he was best suited to lead his fellow Marines in war, no matter how misbegotten and dishonorable that conflict was. Yet he confesses that falling back on duty and being loyal to “his” Marines, while suppressing the infamies of the war itself, became “a washing of the hands, a self-absolution that ignores one’s complicity” in furthering a brutal conflict fed by lies.

As I read those essays, I came to see anew how this country’s senior leaders, military and civilian, consistently underestimated the brutalizing impact of war, which, in turn, leads me to the ultimate lie of war: that it is somehow good, or at least necessary — making all the lying (and killing) worth it, whether in the name of a victory to come or of duty, honor, and country. Yet there is no honor in lying, in keeping the truth hidden from the American people. Indeed, there is something distinctly dishonorable about waging wars kept viable only by lies, obfuscation, and propaganda.

An Epigram from Goethe

John Keegan, the esteemed military historian, cites an epigram from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as being essential to thinking about militaries and their wars. “Goods gone, something gone; honor gone, much gone; courage gone, all gone.”

The U.S. military has no shortage of goods, given its whopping expenditures on weaponry and equipment of all sorts; among the troops, it doesn’t lack for courage or fighting spirit, not yet, anyway. But it does lack honor, especially at the top. Much is gone when a military ceases to tell the truth to itself and especially to the people from whom its forces are drawn. And courage is wasted when in the service of lies.

Courage wasted: Is there a worst fate for a military establishment that prides itself on its members being all volunteers and is now having trouble filling its ranks?

Copyright 2022 William J. Astore

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.

READ MORE:

https://tomdispatch.com/integrity-optional/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..................................