Search

Recent comments

- religious war....

3 hours 12 min ago - underdogs....

3 hours 23 min ago - decentralised....

3 hours 46 min ago - economy 101....

13 hours 43 min ago - peace....

14 hours 31 min ago - making sense....

17 hours 10 min ago - balls....

17 hours 13 min ago - university semites....

18 hours 1 min ago - by the balls....

18 hours 15 min ago - furphy....

23 hours 30 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

"le vainqueur du vainqueur de la terre"…….

The great English literary personality Samuel Johnson (1709-84) had just completed his great dictionary of the English language, which he had been toiling away at for eight years. A coalition of seven London booksellers had commissioned the project eight years previously, at a fixed price of £1,575. At that time Johnson had issued a plan for the work, in the hope of bringing in more funds from patrons.

He had dedicated the plan to Philip Dormer, the Earl of Chesterfield, whom Boswell describes as "a nobleman who was very ambitious of literary distinction." This dedication had actually been suggested by one of the booksellers; it was not Johnson's idea. However, Johnson must have paid a call on the Earl at some point, and been disappointed with the results. He did apparently get a few guineas out of the noble Lord, but it was much less than he had hoped for, and Chesterfield seems to have taken no further interest in the project …

… Until, all those years later, when the dictionary was at last ready for publication (it was actually five years late), Lord Chesterfield published an advance review of it in a magazine named The World, presenting himself as principal patron of the work. This excited Johnson's indignation, and he wrote the following letter to his Lordship.

This is one of the great letters of all time. It is also pure Johnson: learned, elegant, crushing, and bitterly proud.

THE LETTER:

To the Right Honourable the Earl of Chesterfield

February 1755.

My Lord.

I have been lately informed by the Proprietor of the World that two Papers in which my Dictionary is recommended to the Public were written by your Lordship. To be so distinguished is an honour which, being very little accustomed to favours from the Great, I know not well how to receive, or in what terms to acknowledge.

When upon some slight encouragement I first visited your Lordship I was overpowered like the rest of Mankind by the enchantment of your adress, and could not forbear to wish that I might boast myself Le Vainqueur du Vainqueur de la Terre, that I might obtain that regard for which I saw the World contending, but I found my attendance so little incouraged, that neither pride nor modesty would suffer me to continue it. When I had once adressed your Lordship in public, I had exhausted all the art of pleasing which a retired and uncourtly Scholar can possess. I had done all that I could, and no Man is well pleased to have his all neglected, be it ever so little.

Seven years, My lord have now past since I waited in your outward Rooms or was repulsed from your Door, during which time I have been pushing on my work through difficulties of which it is useless to complain, and have brought it at last to the verge of Publication without one Act of assistance, one word of encouragement, or one smile of favour. Such treatment I did not expect, for I never had a Patron before.

The Shepherd in Virgil grew at last acquainted with Love, and found him a Native of the Rocks.

Is not a Patron, My Lord, one who looks with unconcern on a Man struggling for Life in the Water and when he has reached ground encumbers him with help. The notice which you have been pleased to take of my Labours, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it, till I am solitary and cannot impart it, till I am known and do not want it.

I hope it is no very cinical asperity not to confess obligation where no benefit has been received, or to be unwilling that the Public should consider me as owing that to a Patron, which Providence has enabled me to do for myself.

Having carried on my work thus far with so little obligation to any Favourer of Learning I shall not be disappointed though I should conclude it, if less be possible, with less, for I have been long wakened from that Dream of hope, in which I once boasted myself with so much exultation.

My Lord,

Your Lordship's Most humble

Most Obedient Servant

S.J.

READ MORE:

https://www.johnderbyshire.com/Readings/chesterfield.html

-------

GusNotes: some other sources have a different signature: "Sam Johnson".... This abreviation of his own name from Samuel to Sam was a snub to the Earl of Chesterfield....

"Le Vainqueur du Vainqueur de la Terre" — The conqueror of the world's conqueror.

Boswell was a boring dude whom we have also mentioned in relation to Rousseau:

So much for the "Noble Savage"...

Rousseau's sexual romp was with his own servant, an uneducated, unsophisticated lass — but well endowed... She was the ideal mother nature that would not be out of place on the cover of the now defunct magazine "Zoo". Her name was Therese Levasseur. They had met in Paris in 1745. Levasseur was working as a laundress and chambermaid at the hotel where Rousseau took his meals. She was 24 years old at the time, he was 33. According to Rousseau, Thérèse bore him five children — all of whom were abandoned to the "Enfants-Trouvés" home, the first in 1746 and the others in 1747, 1748, 1751, and 1752.

So much for the "Noble Savage"...

Rousseau and Levasseur eventually had an invalid marriage ceremony on August 29, 1768.

Therese provided Rousseau with support and care, and when he died (1778), she was the sole inheritor of his belongings, including manuscripts and royalties. Not so stupid lass after all...

Gossip though has it, that "our friend" Boswell, already mentioned on this site as the companion of Dr Samuel Johnson, was once asked to accompany Therese Levasseur From France to England where Rousseau had taken refuge for whatever reason in 1765, under the protection of David Hume. Though Boswell was younger than Levasseur (she was already 44), he found her conversation very boring — which would have been something amazing considering Boswell's own legendary dullness. But she was still attractive, sexy and eager enough for them to have more than a dozen sessions of intercourse during that short journey to England. Savages.

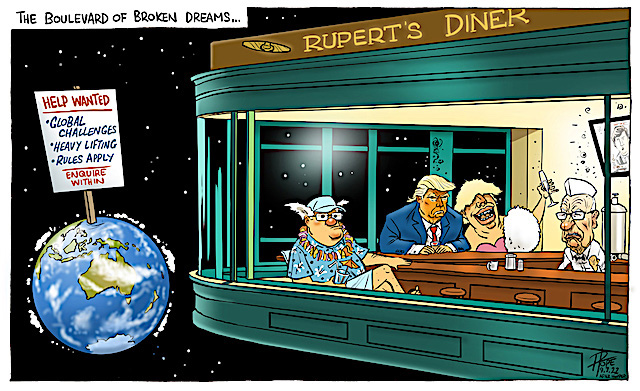

The cartoon at top from Pope... https://www.scratch.com.au

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW§§§§§§§§§§§§§§

- By Gus Leonisky at 25 Sep 2022 - 6:12am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

inevitably destructive methods…...

“Virgil’s Tragic Shepherds”

Julia Scarborough | Wake Forest University

This paper will argue that Virgil’s use of pastoral elements in the Aeneid draws on tragedy to create a destabilizing incongruity between readers’ expectations and epic outcomes. In the Eclogues, peaceful shepherds devote themselves to song; in the Aeneid, in contrast, shepherds enter the epic action at crucial junctures with catastrophic results, culminating in war between Aeneas’ Trojans and the Italians with whom they are fated to join in a new nation.

The clash of pastoral and epic in the Aeneid has troubled both ancient and modern critics. Macrobius suggests in his Saturnalia that Virgil, lacking a Homeric model, simply does not know how to start an epic war. Modern scholars have read the pastoral episode of Aeneid 7 as deliberately evoking the bucolic world of the Eclogues and have identified the outbreak of war as a generic transition from pastoral and georgic to martial epic (Putnam 1970, 1995; Thomas 1999). Some critics have seen this juxtaposition of pastoral echoes with epic warfare as a conflict of values, arguing that Aeneas leads an “imperialist invasion” that destroys an idyllic pastoral society (Putnam 1970, Nethercut 1968). In reaction, other scholars have argued that war is a natural extension of hunting and that shepherds’ participation in violence should not be seen as transgressive (Tarleton 1989, Horsfall 2000).

The role of herdsmen in the Aeneid has engaged and divided critics chiefly because herdsmen become active participants in battle. Unlike herdsmen in the Eclogues, who are exclusively victims, those in the Aeneid repeatedly commit or catalyze acts of violence (Chew 2002, Suerbaum 2005, Kronenberg 2013). The aggression of Virgil’s Latin herdsmen cannot be explained by appeal either to bucolic or to epic models. There is, however, a third genre in which herdsmen do take an active part in violence, both by precipitating crises unwittingly and by starting fights in which they are outmatched. This is Attic tragedy.

Although scholars have long recognized echoes of tragedies such as Euripides’ Bacchae and Heracles in the events of Aeneid 7 (Reckford 1961, Zarker 1969, Wigodsky 1972), discussions of the influence of tragedy on the Aeneid (Fenik 1960, Hardie 1997, Panoussi 2009) have not examined the role played by herdsmen. In Attic tragedy, shepherds bring disruption onto the stage; their good intentions combined with inexperience make them dangerous. Euripides’ Bacchae and Iphigenia at Tauris show groups of herdsmen choosing to launch attacks that go wrong, with disastrous consequences. Sophocles’ Oedipus the King hinges on misguided choices made by two shepherds with the best of motives. This paper will argue that the appearance of shepherds within the larger tragic structures of Aeneid 7 activates expectations from tragedy – that shepherds will leave their ordinary sphere of activity and will unwittingly cause disaster. This tragic role offers a paradigm for the part played by shepherds in the Aeneid, including the poem’s most important shepherd: Aeneas himself (Hornsby 1968, Anderson 1968, Chew 2002). Invoking tensions inherent in the figure of the shepherd in tragedy, Virgil transforms the Homeric metaphor of the hero as shepherd of his people to explore the tragic ironies in which Aeneas is implicated as he struggles to accomplish his constructive “pastoral” mission by inevitably destructive methods.

READ MORE:

https://classicalstudies.org/“virgil’s-tragic-shepherds”

READ FROM TOP.

SEE ALSO: https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/1947

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW •••••••••••••••••••••••••••