Search

Recent comments

- epibatidine....

5 hours 46 min ago - cryptohubs...

6 hours 44 min ago - jackboots....

6 hours 52 min ago - horrid....

7 hours 23 sec ago - nothing....

9 hours 23 min ago - daily tally....

10 hours 45 min ago - new tariffs....

12 hours 37 min ago - crummy....

1 day 6 hours ago - RC into A....

1 day 8 hours ago - destabilising....

1 day 9 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the minefields of hegemony and globalism......

During and after the Second World War, public intellectuals in Britain and the United States grappled with concerns about the future of democracy, the prospects of liberty, and the decline of the imperial system. Without using the term “globalization,” they identified a shift toward technological, economic, cultural, and political interconnectedness and developed a “globalist” ideology to reflect this new postwar reality. The Emergence of Globalism examines the competing visions of world order that shaped these debates and led to the development of globalism as a modern political concept.

How competing visions of world order in the 1940s gave rise to the modern concept of globalism

Shedding critical light on this neglected chapter in the history of political thought, Or Rosenboim describes how a transnational network of globalist thinkers emerged from the traumas of war and expatriation in the 1940s and how their ideas drew widely from political philosophy, geopolitics, economics, imperial thought, constitutional law, theology, and philosophy of science. She presents compelling portraits of Raymond Aron, Owen Lattimore, Lionel Robbins, Barbara Wootton, Friedrich Hayek, Lionel Curtis, Richard McKeon, Michael Polanyi, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Maritain, Reinhold Niebuhr, H. G. Wells, and others. Rosenboim shows how the globalist debate they embarked on sought to balance the tensions between a growing recognition of pluralism on the one hand and an appreciation of the unity of humankind on the other.

An engaging look at the ideas that have shaped today’s world, The Emergence of Globalism is a major work of intellectual history that is certain to fundamentally transform our understanding of the globalist ideal and its origins.

----------------------

ALL THIS SEEMS INNOCUOUS ENOUGH AND DESIGNED FOR THE BETTERMENT OF HUMANKIND.

BUT THIS WOULD BE A MISCONCEPTION TO THINK THAT THIS COULD BE ACHIEVED WITHOUT A FEW, WHAT SHALL WE SAY, DIRTY DEALS, CONFLICTS AND ENTRAPMENTS.

ALREADY, BEFORE WW1, THE EMPIRE SYSTEM OF CONTROLLING THE LOOT OF THE PLANET HAD COLLAPSED.

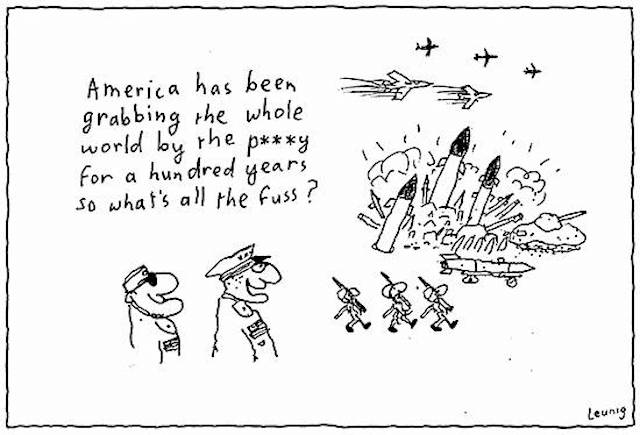

BY 1905, MACKINDER WAS TRYING TO REVIVE A PSEUDO BRITISH EMPIRE BY DEVELOPING THE CONCEPT OF GEO-POLITICS. AS WE’VE EXPLAINED A FEW TIMES ON THIS SITE, THIS IS STILL AT THE CORE OF HEGEMONIC ACTIVITIES OF THE AMERICAN EMPIRE. IF YOU THINK THAT THE USA ARE NOT AN EMPIRE, YOU NEED TO CONSIDER THAT THE USA HAVE MORE THAN 850 MILITARY BASES SPREAD AROUND THE WORLD IN MANY COUNTRIES, AND THEY ARE ABOUT TO ADD A FEW MORE IN THE PHILLIPINES TOMORROW.

MEANWHILE OVER THE YEARS, POLITICAL FORCES OF ONE COUNTRY OR ANOTHER HAVE SET TRAPS OR "MANIPULATED POPULATIONS" TO WEAKEN THEIR OPPONENTS, TO DESTROY THEM OR TO CONQUER THEM. IN ORDER FOR THESE TO WORK WITHOUT REVOLUTIONS/INSURRECTIONS/RETALIATIONS OF PEOPLE, THESE TRAPS NEED TO BE MORALLY EXPLAINED, SUPPORTED BY HYPOCRITICAL EXCUSES OR MANAGED BY BLAMING SOMEONE ELSE FOR THE DAMAGE.

WE KNOW OF THE “OPIUM WARS” IN CHINA. THIS WAS A POWERFUL ENTRAPMENT OF A POPULATION, FOR THE PROFITS OF BRITAIN AND AMERICA’S ELITE.

MORE RECENTLY, THERE HAS BEEN SOME POWERFULLY CONSTRUCTED ENTRAPMENTS OF ONE OWN POPULATION IN ORDER TO JUSTIFY THE HEGEMONY.

THE MOST RECENT ENTRAPMENT BY THE AMERICAN EMPIRE IS THE UKRAINE/RUSSIAN CONFLICT. THE BLAME WILL BE PLACED SQUARELY AT THE FOOT OF PUTIN WHILE THE SET UP WAS PURELY AMERICAN. IN ORDER TO MAKE IT STICK IN THE MIND OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC, THERE HAS BEEN A SYSTEMATIC “ENTRAPMENT” OF PUBLIC OPINION IN AMERICA AGAINST RUSSIA FOR MORE THAN 100 YEARS. AND THIS RUSSOPHOBIA IS A POWERFUL MANIPULATION THAT IS VERY HARD TO SHAKE WHILE THE MEDIA ARE ON BOARD WITH THIS FAKE SENTIMENT.

SO WHO DESIGNS AND CONTROLS THE SET-UPS THAT ARE GOING TO BECOME ENTRAPMENTS FOR OTHER COUNTRIES AND/OR INTERNATIONAL EVENTS?

WE KNOW THAT THE “MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD” WAS SET UP BY MI6.

WE KNOW THAT THE “ARAB SPRING” WAS FOMENTED BY MI6.

WE KNOW THAT SADDAM HUSSEIN WAS SET UP WITH FAKE WMDs STORY BY THE CIA.

WE KNOW THAT WHITLAM WAS SET UP BY THE CIA AND WAS TRIPPED BY THE ENGLISH CROWN.

WE KNOW THAT DE GAULLE TRIED TO PREVENT THE UK TO JOIN THE COMMON MARKET, BECAUSE HE KNEW THIS WOULD BECOME WHAT IT DID UNTIL BREXIT.

WE KNOW THAT GERMANY IS SENDING TANKS TO UKRAINE, ONLY BECAUSE AMERICA IS “GOING TO SEND ABRAMS TANKS” ALSO BUT “NOT JUST YET”.

WE KNOW THAT ASSAD IN SYRIA HAS BEEN FACING THREATS FOR A WHILE AND THAT BY 2009, AFTER HAVING REFUSED TO LET AN AMERICAN SPONSORED PIPELINE THROUGH SYRIA, WAS SET UP WITH A SUNNI REVOLUTION WHICH LED TO AMERICA BASICALLY CREATING “DAESH”. ASSAD GOT SAVED BY RUSSIA, BUT IS STILL PAYING THE PRICE AS THE AMERICANS ARE STEALING THE SYRIAN OIL IN THE EAST OF THE COUNTRY. MEANWHILE ISRAEL NIGGLES DAMASCUS INTO RETALIATORY SENTIMENTS THAT WOULD LEAD TO FULL OUT WAR IF ASSAD TOOK THE "BAIT".

WE HAVE INKLINGS THAT 911 WAS A SET UP THAT PROBABLY WENT BEYOND EXPECTATION AND RATHER THAN BRING THE “GUILTY” TO JUSTICE, THEY WERE “ELIMINATED” BY IMPRISONMENT IN GUANTANAMO AND ASSASSINATED, SAY BIN LADEN, TO PREVENT THE TRUTH BEING INVESTIGATED.

WE KNOW THAT JULIAN ASSANGE HAS BEEN REPORTING THE TRUTH AND THE AMERICAN EMPIRE SET UP A FEW ENTRAPMENTS TO CAPTURE HIM. WE KNOW THAT ASSANGE CANNOT EXPECT JUSTICE.

RECENT REVELATIONS HAVE HINTED THAT THE WATERGATE AFFAIR WAS A SET UP BY THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY TO ENTRAP NIXON.

WE KNOW THAT JFK WAS ELIMINATED BECAUSE “HE WAS TOO POPULAR” — FOR POLITICAL OR SOCIAL (SEXUAL AFFAIRS) ENTRAPMENTS TO WORK. HIS BRAINS WERE BLOWN OUT BY AN AR-15 EXPLOSIVE BULLET EXCLUSIVELY USD BY THE SECRET SERVICE. LEE HARVEY OSWALD WAS SHOT DEAD SO HE COULD NOT TELL THE TRUTH OF HIS INVOLVEMENT IN THE GREATER PLOT.

GADDAFI WAS ENTRAPPED A FEW TIMES BUT MANAGED TO "ESCAPE", THOUGH BY THEN END, NATO AND THE USA INVENTED SOME FAKE MORALLY-BASED EXCUSES ("HE IS KILLING HIS OWN PEOPLE") TO DESTROY LIBYA (AND KILL TWICE AS MANY).

TURKEY HAS BEEN THE SUBJECT A FEW POLITICAL AND DIPLOMATIC TRAPS. THE STUBBORNNESS OF ITS LEADER IS HELPING TURKEY TO WALK THROUGH THE INTERNATIONAL MINEFIELDS.

SO THE ARTICLE BY THE CATO INSTITUTE THAT FOLLOWS NEEDS TO BE READ IN THIS LIGHT: GOODNESS IS THE HONEY TO KILL YOU. BUT FIRST A FIX ON THE CATO INSTITUTE...

The Cato Institute' is an American libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C.It was founded in 1977 by Ed Crane, Murray Rothbard, and Charles Koch,[6] chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Koch Industries.[nb 1] Cato was established to have a focus on public advocacy, media exposure and societal influence.[7] According to the 2020 Global 'Go To Think Tank Index Report (Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program, University of Pennsylvania), Cato is number 27 in the "Top Think Tanks Worldwide" and number 13 in the "Top Think Tanks in the United States".[8]

The Cato Institute is libertarian in its political philosophy, and advocates a limited role for government in domestic and foreign affairs as well as a strong protection of civil liberties. This includes support for lowering or abolishing most taxes, opposition to the Federal Reserve system and the Affordable Care Act, the privatization of numerous government agencies and programs including Social Security and the United States Postal Service, demilitarization of the police, and adhering to a non-interventionist foreign policy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cato_Institute

WHAT THE CATO INSTITUTE TELLS US:

For much of its history, the United States has not faced serious security threats from nation‐ states. Its expansive ocean moats and weak neighbors simplified its security problem even before it became a great power; geographic distance and European distraction often protected what power alone could not.

After the end of the Civil War, America added to those assets political unity and economic might. With few exceptions, the United States has been free from the worst sorts of external dangers. It took a freak accident of world historical scale—the military collapse of French armies in May 1940—to create a serious geopolitical threat to the United States. The efforts to meet Hitler’s threat set the stage for Stalin’s, because five years of war destroyed the industrial world and put the Red Army in the heart of Europe. In short, for a few decades following 1940, the United States arguably did face a legitimate external threat: the possibility that the resources of the industrial world could be politically united and turned against the Western Hemisphere. Those conditions have long since disappeared; yet their intellectual influence lives on in contemporary American grand strategy. The United States maintains the world’s most powerful military, which makes its presence felt overseas through a political system of globe girdling alliances. Those expensive efforts aim to prevent a renewed power competition such as the one that led to World War II and the Cold War. Such a competition is generally regarded as catastrophic, either because it would produce a potential hegemon such as Germany or the Soviet Union, or because the United States would inevitably be drawn into war in order to forestall such an outcome. Instead, America pursues a grand strategy of primacy, which aims to stop dangerous threats to its security resulting from competition among nation‐ states.

America does indeed face threats from nation‐ states, but those threats stem from its primacy strategy rather than being prevented by it.

America does indeed face threats from nation‐ states, but those threats stem from its primacy strategy rather than being prevented by it. The geopolitical nightmares of the mid‐ 20th century are probably gone forever; at any rate, they are at least so distant that we can have little confidence that preparing for them provides any benefit. At the same time, the remoteness of geopolitical threats to the Western Hemisphere does not mean an end to security competition elsewhere. America’s network of alliances and interests provides it with an incentive to try to manage regional politics across the globe. Such management is likely to be more difficult than many expect. If management fails, primacy has the potential to entangle the United States in unnecessary conflicts, while convincing policymakers that they are getting a bargain in the process. Strategists would do well to reevaluate primacy before its costs add up.

The rest of this chapter proceeds in three parts, followed by a concluding section. First, I sketch primacy’s strategic logic, focusing on its purported anti‐ hegemonic security benefits. Second, I argue that a number of factors make the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon extremely unlikely, if not impossible, independent of American policy choices. Third, I examine the potential pitfalls of the American alliance network. Those alliances are likely to fail to prevent conflict in the situations where it is most likely, and they are unnecessary in most other circumstances. Conversely, they make it likely that Washington will take on costs it ought not to.

The Logic of Primacy

Stephen Brooks, John Ikenberry, and William Wohlforth have rendered a thorough defense of the strategy of primacy.1 In the process of attacking various proposals for strategic retrenchment, they explicate primacy’s logic with rare and exceptional clarity. This chapter takes their treatment as a focal point for discussing America’s current grand strategy.

Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth argue that America’s grand strategy has sought to defend three main objectives since the beginning of the Cold War: “security, prosperity, and domestic liberty.”2 Those objectives have required, most centrally, “managing the external environment to reduce near and long‐ term threats to U.S. national security.” Managing the external threat environment requires political and military tools; it “underlies what is arguably the United States’ most consequential strategic choice: to maintain security commitments to partners and allies in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East.” During the Cold War, those commitments “served primarily to prevent the encroachment of Soviet power into regions containing the world’s wealthiest, potentially most powerful, and most resource‐ rich states.” After the Cold War’s end, the major commitments aimed “to make these same regions more secure, and so make the world safer for the United States,” while constituting “a hedge against the need to contain a future peer rival” if the strategy failed.3

The logic of primacy is simple: U.S. security commitments dampen “the most baleful effects of anarchy.” They are the edifice of the unipolar world, thus projecting a lopsided and stable balance of power into the world’s most important regions. On the one hand, “the United States’ overseas presence gives it the leverage to restrain partners from taking provocative action.” On the other hand, “its core alliance commitments also deter states with aspirations to regional hegemony from contemplating expansion,” which, in turn, “make its partners more secure, reducing their incentive to adopt solutions to their problems that threaten others and thus stoke security dilemmas.” Reducing security fears for everyone has a long‐ term pacifying effect, thereby deterring entire regions from military buildups that might precede a major bloodletting or challenge U.S. unipolarity.4

The alternative to U.S. primacy is a much darker, dangerous world that threatens core American interests. Most centrally, “China’s rise puts the possibility of it attaining regional hegemony on the table, at least in the medium to long term.” China’s neighbors are not strong enough to balance against it, and so it “follows that the United States should take no action that would compromise its capacity to move to onshore balancing in the future.” A security competition in the Pacific would likely have a decisive winner, resulting in Washington’s worst nightmare: a regional hegemon dominating a wealthy region, capable of menacing the Western Hemisphere. In short, by “supplying reassurance, deterrence, and active management, the United States lowers security competition in the world’s key regions,” thus preventing a power shift away from a unipolar world and “deterring entry of potential rivals.”5

Moreover, the central fact of unipolarity means that the United States has little reason to fear costs from its alliances. According to Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth, the notion of entrapment is incoherent: it inverts Thucydides great dictum into “the weak do what they can and the strong suffer what they must.” The enormous power differential between the United States and its allies means that they are heavily dependent on it; Washington can use its leverage to manage allied policy, not the other way around.6

In sum: primacy locks in an extremely favorable unipolar distribution of power. By deterring aggressors and reassuring partners, it brings peace and tamps down a competitive structure of world politics that might produce more dangerous power distributions. The most dangerous of those is the emergence of a regional hegemon in Asia, which is a significant risk in the event that America disengages in the Pacific. Because there are few costs to American alliances, primacy provides many benefits for only marginally increased expenditure.

Regional Hegemons

The core goal of primacy’s competition‐ dampening logic is anti‐ hegemonic in nature. Evaluating primacy, therefore, requires assessing the degree to which America must fear a potential hegemon in Eurasia. It is important to understand the character of a hegemonic threat. Historically, the great fear has been a potential “battle of the supercontinents”: a struggle between the politically unified Eurasian supercontinent stretching from West Africa to the Bering Strait and the American supercontinent stretching from the tip of Alaska to Cape Horn. That contest would favor the Eurasian power, which would dominate the American supercontinent in people, resources, and capital by an order of two to one or more. Its gross domestic product (GDP) would far outstrip the Western Hemisphere’s, and it would have a much greater surplus of wealth to pour into military might while still maintaining a healthy civilian economy.7

However, even that kind of contest would not pose a threat of conquest to the United States, at least not until very late in the game. The great geopolitical analyst John Spykman, whose nightmare was the political unification of the Eurasian supercontinent, believed that at least one half of the Western Hemisphere was militarily defensible. That “quarter‐ sphere” would stretch from central Canada to the bulge of Brazil. The Amazon jungle is impassible in the south. Greenland, Alaska, and northern Canada might be lost to the Eurasian power, but the United States could defend a line running across the middle of Canada, close to the center of American power. Maritime and‐ land based air power could easily prevent an amphibious assault on the quarter-sphere—the invasion of Normandy was successful by a very thin margin, and the Eurasian state would not have nearly so favorable conditions.8 Defending the quarter‐ sphere would require great effort and vigilance, but it could be held militarily.

The bigger threat would be economic and ideological. Spykman feared that the American supercontinent would be slowly strangled to death by economic warfare. The Eurasian power could embargo its own ports and blockade the Western Hemisphere. Those measures would have two important effects. First, though not vulnerable to conquest, many South American countries have historically depended on markets in Europe for their survival. The United States, Spykman argued, simply could not absorb enough of the raw materials produced below the equator to maintain a viable hemispheric economy. The Eurasian power would be able to economically coerce Argentina, southern Brazil, and other states into its own sphere of influence. Second, Spykman argued that there were 11 strategic raw materials critical to modern warfare that were not available in sufficient supply in the quarter‐ sphere. With an active military campaign burning through those resources quickly, the forces of the American supercontinent would gradually become less potent. Eventually, Spykman argued, military collapse would ensue.9

There is good evidence that Spykman was too pessimistic about strategic raw materials and that the quarter‐ sphere could probably be defended indefinitely.10 Nevertheless, organizing the American supercontinent for defense would present enormous difficulties. A hemisphere‐ wide basing structure for naval and airpower would have to be built in order to prepare a defense at all points. The region would have to integrate its disparate economies at a breakneck pace, while bearing all the pains of adjustment. That kind of large‐ scale military cooperation might prove difficult even under threat of war, and it is likely that most states would have to cede some sovereignty on major economic and military matters to the United States. In the optimistic case, a political federation centered in Washington would be the result.11

The weaker states in the Western Hemisphere might resist federation. In addition to nationalist reasons, along with any economic pressures the Eurasian power could bring to bear, many Latin American societies have proved to be quite vulnerable to extreme ideologies. The heavily skewed class structure of those countries creates natural constituencies for the authoritarian right among the upper classes and the military, while the masses and their elite representatives can fall prey to the radical left. The Eurasian power would, therefore, have plenty of opportunity to try to pry loose vulnerable countries or to stoke proxy wars in the Western Hemisphere. Federation might not be possible; political unity might be achievable only by the sword. The United States might need to become an imperial or quasi‐ imperial state in its foreign relations.12

Major domestic transformations would also occur. There is reason to doubt that the market mechanism would be sufficient to manage the economic transformation under wartime pressures; the government would probably grow rapidly to a very large size and take control of large swaths of the economy. Americans would suffer a decline in their standard of living as massive resources were poured into defense, and American society would become more regimented as the national security state grew. The United States would become an armed camp, ruling over an empire. One wonders how long democracy would survive under such circumstances. Avoiding those threats to American core values has been the root of Washington’s policy of maintaining the political division of industrial Eurasia, if necessary by war.13

At their height, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia both plausibly threatened to unify industrial Eurasia and to turn its resources against the Western Hemisphere. Those regimes possessed several advantages that made a bid for hegemony a worrisome possibility. First, they dominated the local balance of power. Measured by energy consumption and steel production, the 1942 Greater German empire controlled 59 per cent of European power, with the rest evenly divided between Britain and Russia. The Soviet Union in 1952 controlled 43 percent of European economic power, outweighing its nearest rival two to one. It also faced a much more divided coalition, composed of Britain, France, West Germany, Italy, and the Benelux states; coordinating contributions from all of them would be required to check the threat locally.14

Second, both potential hegemons had invested heavily in powerful land armies at the expense of their navies. The German army was more than 3 million strong, and it slightly outnumbered the army of the much more populous Soviet Union in 1942. The Red Army outnumbered the rest of the European continent three to one in 1952. Both forces were finely tuned fighting machines. That reality meant that either power could conquer the maritime approaches to the West ern Hemisphere, consolidate its power, and only then build a navy.15 Third, both the Nazis and the Soviets had a territorial springboard and a geographic route to conquest. The Greater German empire stretched from Brest to Moscow, where Hitler nearly defeated the Soviet Union in 1941. The disintegration of the Russian state would have given Hitler access to the Pacific. The Soviet empire ran from the Bering Strait to the inter‐ German border, and a mechanized assault could cut through the central European plain to the Atlantic. Fourth, both powers possessed powerful ideologies that could appeal to countries in the Western Hemisphere.

Even with all those advantages, a number of dominoes would have had to fall for either Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union to have created the Eurasian supercontinent. Hitler failed in his drive across Russia; had he succeeded, he would have still needed either to defeat the Japanese and the British or to come to some sort of cooperative accommodation with them. The Soviet Union would have faced the same problems had it reached the Atlantic. The task of becoming a Eurasian hegemon is a Herculean labor, even for the most plausible candidates. The only country mooted for the honor today is China, and its task is orders of magnitude harder.

First, measured by GDP at world prices, China contains about 41 per cent of the wealth located in the major Asian economies (Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, and Taiwan). But China is only a third or so wealthier than its nearest rival Japan, which would be a natural coalition leader against it.16 Moreover, China’s per capita GDP is quite low, making it unclear how much of its wealth is surplus that could be easily mobilized for military purposes.17 The economic balance is expected to shift more toward China over time, but even under favorable assumptions, it will be several decades before China obtains a position in Asia that resembles those held toward Europe by Greater Germany in 1941 or the Soviet Union in 1945. Such projections also downplay the many social and economic problems coming down the road for Beijing; many believe its aging population, social unrest, environmental degradation, and societal stratification could limit its growth.18

Second, were China to obtain a power position like that of potential hegemons past, it would still face even more challenging tasks than they. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is the largest ground force in the world, but it hardly compares with the fighting power of the Wehrmacht or the Red Army. The PLA Navy is not yet capable of fighting outside its coastal waters.19 Most important, China would have to build both forces simultaneously if it had designs on conquest, because its powerful maritime rival Japan is unlikely to sit idly by as China cuts up its neighbors.

Third, the geographic hurdles facing a Chinese bid for hegemony are large. To control shipping to the Western Hemisphere, China would need to dominate the waters out to at least the “second island chain,” which marks a line roughly from Japan to Australia. Any Chinese naval aggression would be complicated by the need to subdue or coerce several hostile maritime strongholds, with not inconsiderable wealth and power of their own: South Korea, Taiwan, and Australia. The PLA Navy would be forced to launch multiple amphibious assaults against hostile coastlines defended by land‐ based airpower—a feat not yet accomplished in world history. It seems particularly dubious that China could win the battle for the air, sea, and undersea supremacy necessary to subdue Japan.

Fourth, most of China’s targets would likely have nuclear weapons. India and Russia already possess substantial nuclear arsenals, and Japan could obtain an operational capability very quickly. Taiwan, South Korea, and Australia have all had nuclear programs in the past, and they possess the technical and material resources to restart them.20 Most parties could obtain secure second‐ strike forces without much difficulty. It is hard to see how a state possessing secure nuclear forces can be forced to yield on core issues of sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Fifth, supposing that China somehow solves the nuclear problem with Asian states and becomes a hegemon in the Pacific through conquest or coercing others into being its vassals, it would still need to get to Europe. Doing so would require defeating a Russia equipped with a Cold War–size nuclear force, projecting power across the Urals, and conquering a European center of economic power larger even than China, one that would have no doubt watched the unfolding drama in Asia with great interest. Failing that, the United States would be able to engage in bustling trade with Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. No doubt that trade would still require considerable adjustment on the part of American markets, but not likely the transformational adjustment threatened by a supercontinent showdown. Such an outcome would also require considerable economic adjustment in China itself, whose economic rise has been driven in large part by trade with North American markets; that possibility casts further doubts on the incentives to pursue the labors of conquest.

In short, Eurasian power will stay divided. Asian power will stay divided. In all likelihood, robust trade will continue across the Pacific, even if its terms become more favorable to Asia. Under the most favorable circumstances, attempting to become a regional hegemon is a wildly ambitious goal. In present circumstances, it is simply impossible. Fears of an America transformed by living under constant geopolitical threat are needless. Actual hegemonic challengers have vanished from this earth.

None of that is to say that there will be no war, conflict, or even cross‐ border conquest in Asia. Nor is it to say that China will not heavily shape political and economic order in Asia, perhaps at American expense. I argue only that the security concerns cited by advocates of primacy are misguided. With regard to security threats, a shifting balance of power matters only insofar as it could produce a potential hegemon. Power competition in Asia, therefore, has no relevance to American security.

The Dangers of Alliances

Yet nation‐ states still pose some dangers. Much more likely than the emergence of a regional hegemon is the potential for continued U.S. management of regional politics to go eventually awry. If the security problems of anarchy are even relevant at all in the contemporary environment, then the goal of dampening their competitive effects is much more difficult than primacy’s advocates admit. Only the most motivated, highly revisionist actors will challenge a status quo that has so many incentives against war. If security competition ensues and turns violent, American decisionmakers could well decide to join the war they could not prevent. Such wars would probably make no sense for the United States with regard to power politics, absent the endorsement of a primacy strategy. In short, if political management fails to head off security competition, primacy has failed on its own terms. The consequences could be worse than a simple failure to produce benefits: the only contemporary security threat from nation‐ states is that America will needlessly fight in their wars.

Primacy and the Goldilocks Problem

A broad range of research in international relations suggests that, under most circumstances, great power politics in Asia is likely to be peaceful. Defensive realists have long argued that the costs of conquests are extraordinarily high; their theories are especially relevant in Asia, where maritime geography and the likely presence of secure nuclear arsenals provide a large defensive advantage.21 Liberal arguments often come to the same conclusion by a different route: economic exchange has skyrocketed in Asia, creating the capitalist interdependence that is often said to incentivize peace. Modern economies have become more difficult to exploit, meaning that fewer economic gains are to be had from conquest.22

One could further add cognitive, normative, and biological arguments: Steven Pinker has recently argued that humans are moving away from warfare for all those reasons, while John Mueller has contended that major war among modern, industrial societies has already gone the way of dueling among people.23 Even the Asian absence of two traditional liberal causes of peace—widespread democracy and dense institutionalization—has become a less compelling worry. Although Asia lacks the institutionalization of European politics, it is not exactly devoid of institutions, which have increased in number, membership, and overlapping linkages since the end of the Cold War.24 More Asian regimes are democracies than ever before, and China’s autocratic regime appears to bias its external politics in favor of compromise, so that it can maintain domestic control.25

However, one might argue that grand strategy should not assume “normal” times and actors. In the past, some states anticipated—and bore—tremendous costs to obtain their national objectives. The factors that restrain mature liberal democracies in secure regions may not apply to more nationalist, authoritarian, and state‐ capitalist countries in a region of shifting power balances. The presence of highly revisionist regimes, which are insensitive to the costs of war and inducements to peace just noted, might threaten Asia’s peace.

Many defensive realists’ projections of world politics assume that security is the dominant state preference, and they define security narrowly as the protection of the homeland. However, a body of research suggests that some states prioritize other values as highly as security. For instance, Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth argue that “states have preferences not only for security but also for prestige, status, and other aims, and they engage in tradeoffs among the various objectives.” Moreover, states often define “security” broadly in relation to “many and varied milieu goals.”26 If Asia’s politics are driven by those sorts of motivations, then even secure states may, nonetheless, engage in power competition, with potentially disastrous results.

Furthermore, offensive realism doubts the validity of claims about defensive advantage and easy signaling of intentions altogether. Offensive realists argue that the deadly logic of security competition in an uncertain world dominated the effects of institutions, ideas, democracy, and capitalism in the past. The theory may remain powerful today, as Brooks, Ikenberry, and Wohlforth contend, and its predictions are grim: “The withdrawal of the American pacifier will yield either a competitive regional multipolarity complete with associated insecurity, arms racing, crisis instability, nuclear proliferation, and the like, or bids for regional hegemony, which may be beyond the ability of local great powers to contain (and which in any case would generate intensely competitive behavior, possibly including regional great power war).”27 Offensive realism predicts a world full of revisionists, checked only by large centers of power.

Primacy’s core difficulty is that if highly motivated revisionist states exist, they will be incredibly difficult to manage even with the presence of the American pacifier. Such states are least likely to credit American threats and promises, and they are most likely to accept the costs of American punishment. Primacy has a Goldilocks problem: conditions can be neither too hot nor too cold. Challengers to the American order must be so strongly motivated that they are willing to pay the very considerable costs associated with modern conflict, but not so strongly motivated that the prospect of fighting the United States fails to deter them. Perhaps that describes the world in which we live, but it seems far more likely that only a few states are motivated by an amount of revisionism that is “just right.”

Primacy depends on allies and adversaries alike being responsive to American security guarantees. The more states prefer other objectives to security, the less likely American security blandishments are to influence their behavior. Revisionist opponents will have good reason to believe they have a stronger will than the United States on critical non‐ security issues, and challenges are likely. The simple fact that such states will care far more about the issue in dispute will, thus, incentivize a gamble that the United States will decline to intervene. Even if the United States chooses to fight and even if the United States can deny the challenger its military objectives, revisionists motivated by non‐ security aims will have good reason to believe they can win the resulting contest in pain. How long will Washington continue to bear costs over a quarrel in a faraway country between people about whom it knows nothing?

If the revisionists are allies of the United States, they may simply value the issue at hand more than they value security guarantees. Alternatively, they could make the opposite bet, gambling that the United States can be convinced to support their objectives, however grudgingly, or that less resolved regional actors will be deterred by that possibility. In any case, a basic point holds. Revisionists must take risks to obtain their objectives. A state that places a very high value on non‐ security gains is much more likely to take risks. It is difficult to imagine the Goldilocks revisionists for whom U.S. commitments represent the decisive factor in their calculus.

Those dangers are particularly evident when states seek positional goods, such as status or prestige, that tend to be zero‐ sum. For instance, Wohlforth argues that status is connected to material capabilities and that “dissatisfaction [with status] arises not from dominance itself, but from dominance that appears to rest on ambiguous foundations.”28 Multipolar environments, he argues, cause status dissatisfaction because there are multiple indexes of capability (e.g., military, naval, economic) across which states compare themselves, all of which provide different assessments of status. An illustrative example is the Crimean War, where Russia pursued status goals against an overwhelming coalition whose members themselves had no security concerns. Wohlforth argues that Russia’s power on land and its ambiguity about Britain’s economic power led Russia to pursue a higher rank than it could secure with its capabilities.

Applying those arguments to East Asia should give us pause. Though Wohlforth argues that unipolarity should produce an unambiguous status hierarchy, East Asia looks similar to the Crimean example. Using Wohlforth’s metrics, China has the largest ground force in the world and the ability to rapidly augment it. That point of comparison could be relevant for potential flash points such as the Korean Peninsula. The Chinese navy is no match for its American counterpart in the open ocean, but it is growing and modernizing and would likely be operating close to its own coasts in a potential clash. Economic measures throw the problem into bold relief. Using an index of energy consumption and iron and steel production, Britain was 13.5 times more powerful than Russia at the time of the Crimean War. China’s GDP is roughly half of America’s now and is projected to overtake Washington in the next couple of decades.29 Tsarist Russia had not undergone the Industrial Revolution and misunderstood its economic implications. By contrast, Chinese growth is well understood and is the most salient feature of contemporary East Asian politics. There seems ample cause for the Chinese to experience status dissatisfaction across a number of metrics, which could be very difficult to manage through American commitments in the region.

Offensive realist revisionists pose a similar problem. Offensive realism predicts a bleak world of relentless security competition because of its focus on uncertainty. States cannot reliably predict one another’s intentions—a very difficult task in the present, and an impossible one any distance into the future. “In a world where great powers have the capability to attack one another and might have the motive to do so,” John Mearsheimer argues, states “must at least be suspicious of other states and reluctant to trust them.” The result is that “each state tends to see itself as vulnerable and alone, and therefore it aims to provide for its own survival.” The only reliable provision for security is more power.30 Unfortunately, that conclusion means that “alliances are only temporary marriages of convenience: today’s alliance partner might be tomorrow’s enemy,” and vice versa. Offensive realist predictions are, therefore, trouble for primacy. Friends and foes will be looking to take advantage of one another, and they will not be prone to regarding the commitments the United States made a long time ago as especially relevant to the present. Indeed, “great powers are also sometimes unsure about the resolve of opposing states as well as allies.” That uncertainty leads to calculated risks by aggressors and allies who begin to take security measures as though the United States may not intervene. Furthermore, because “fighting wars is a complicated business in which it is often difficult to predict outcomes,” revisionists of all stripes have incentives toward innovation and clever strategies. Fait accompli tactics that quickly revise the status quo and then dare others to push for reversal, or new military technology and doctrines that give revisionists hopes of a quick victory, are likely to be common in an offensive realist world. American commitments will be of questionable value for deterrence or reassurance under those circumstances.31

Nuno Monteiro has recently laid out the problematic relationship between offensive realist assumptions and American strategy. He argues that primacy—which he calls a strategy of “defensive dominance”— tends to create extremely dedicated minor power revisionists, for two reasons. First, primacy is a strategy of locking in the status quo through formal or informal commitments to regional actors. A favorable status quo for major regional powers will often come at the expense of local minor powers, which may be inclined to try to reverse it: for both security reasons and the non‐ security reasons noted earlier, a unipolar world will reduce the “value of peace” for some countries.

Second, the most prominent aspects of the status quo being locked in are the extant territorial, alignment, and power distribution conditions. Those conditions pose no special problems for a state that can ensure its own survival, but minor powers by definition cannot. They exist in a state of radical uncertainty regarding the intentions of the unipole. Lacking the hope of an external sponsor should the unipole turn on them, recalcitrant minor powers have incentives to build up their military power, pursue nuclear weapons, and change the status quo through salami tactics. Those actions are just the sort of security competition that primacy hopes to prevent, and they are likely to precipitate a clash with the unipole.32

Recent scholarship in international relations highlights additional circumstances under which the management of regional politics will be difficult. Timothy Crawford’s work identifies two conditions that make restraining others—or “pivotal deterrence” in his terms—more difficult: when the pivot is trying to defend nonvital interests and when potential adversaries and allies have other alignment options. Empirically, his view is not particularly sanguine. Crawford’s chapter on 1870s’ Germany is subtitled “Why Bismarck Had It Easy” and shows that non‐ Bismarckian strategists in less propitious circumstances have a tough task. His chapter on America’s failure to prevent war between Pakistan and India in the 1960s demonstrates just how difficult restraining major Asian powers can be, and it is an imperfect but useful analogue for the type of problem a contemporary primacy strategy may face. And, of course, his chapter on Britain in 1914 should provide a cautionary tale to any power trying to “hold the balance”—those who want only to prevent war are most likely to be chain‐ ganged into a conflict they would prefer to avoid.33

Similarly, Jeremy Pressman argues that for alliance restraint to work, the restrainer must avoid deception by its partner while unifying its national leadership and political institutions around costly measures of power mobilization. That his book begins with the example of the United States’ failure to prevent the 1956 Suez crisis is noteworthy.34 Tongfi Kim’s work on entrapment notes that “there is a reputational cost for non‐ involvement” in an ally’s wars and that security commitments “increase the costs of non‐ involvement and make it rational for self‐ interested states to become entangled into undesirable situations”— surely a concern in East Asia.35 Even Dominic Tierney, who argues that restraint will be more common than chain‐ ganging in alliances, identifies salient conditions that lead to chain‐ ganging: an especially hawkish partner pulling its moderate dovish ally over the cliff and within defending coalitions. Since the United States is certainly not wholly averse to the use of force and is generally trying to protect the status quo, those conditions seem especially relevant.36

In sum, for primacy to work, the weight of U.S. power must be the decisive influence by which local actors make decisions about whether to engage in security competition. The many powerful forces working for peace—geography, nuclear weapons, trade, and so forth—will often produce very low levels of security competition with or without an American presence. Only highly dedicated revisionist actors, motivated either by non‐ security gains or the uncertainty of the international system, are likely to pursue a power competition. They are just the sort of actors, however, whom it will be difficult to manage. Competition will probably ensue anyway, with or without American engagement. Primacy, therefore, faces a Goldilocks problem: Asian politics will frequently be too cold for American commitments to be useful or too hot for them to handle. Only if the temperature of revisionism is “just right” does primacy have any hope of contributing to regional security.

The Dangers of American Alliances

Primacy poses more dangers than simply failing to achieve its goals. Failed regional management may well induce American policymakers to fight, either to end the wars they could not prevent or for other reasons. Here, I highlight two considerations that might drive such a decision: (a) concerns about the credibility of American commitments and (b) expanding definitions of American core interests.

Primacy depends heavily on credibility: the belief among interested actors that, in the final reckoning, the United States will go to war to protect the status quo it has promised to defend. A related important belief is that the United States will go to war only to protect the status quo it has promised to defend. A primacy strategy engages in a combination of “extended” and “pivotal” deterrence: it aims to convince revisionists of all stripes of American willingness to punish those who seek to overturn the status quo.

As discussed earlier, the world with revisionist states motivated enough to make primacy useful will also be one where American credibility is open to question. Offensive realist states will be motivated by a view of uncertainty that sees alliances as often unreliable alternatives to self‐ help. States with non‐ security motives will have good reason to believe that they hold the balance of resolve on non‐ security issues far from American shores. In either case, there will be ample reason for risk‐ acceptant revisionist states to consider gambling against American intervention.

To be clear, revisionists would not be doubting U.S. capabilities, although clever diplomatic and military strategies might lead them to believe they could temporarily revise the status quo. Rather, revisionists would doubt that America’s interests were large enough to justify the costs of war. Daryl Press, who generally emphasizes the decisive influence of power considerations in deterrence decisions, argues that “adversaries will doubt whether the United States will take costly actions to defend interests of secondary or tertiary importance.” A good historical example is the German military’s view of the Anschluss. Even though senior Wehrmacht officers believed that Britain and France could intervene and defeat Germany during an invasion of Austria, they endorsed Hitler’s plans, largely because they doubted that the Western powers would risk war over the unification of German speaking peoples in one country.37

In the event that deterrence fails, what will Washington do when faced with a challenge to the status quo? There is good reason to believe that policymakers will follow through on their commitments, even though the costs of war may be quite disproportionate to American stakes in the issue under dispute. After all, wouldn’t a failure to defend the status quo reveal the entire primacy strategy to be a bluff? Revisionist states might be expected to draw that conclusion, no matter how the United States framed the situation. One does not need to believe that states carefully monitor each other’s past actions in order to draw inferences about likely future behavior to credit that notion. Backing down over a commitment might clarify for many interested parties American interests in defending other commitments—all far from U.S. shores and protecting interests far more important to others than to Washington— that look just like it.

Regardless of whether revisionist states make such inferences, it is crystal clear that American decisionmakers believe they do. Harry Truman’s decision to intervene in Korea was driven by the belief that the Soviet Union would draw inferences about American willingness to fight. “If we let Korea down,” Truman argued, “the Soviet will keep right on going and swallow up one piece of Asia after another. If we were to let Asia go, the Near East would collapse and no telling what would happen in Europe.” Conversely, “if we are tough enough now, if we stand up to them like we did in Greece three years ago, they won’t take any next steps.”38 The American commitment in Vietnam hinged on credibility concerns as well, especially with regard to what its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization would think. Lyndon Johnson believed that escalation was required because “to leave Vietnam to its fate would shake the confidence of all these people [i.e., other U.S. allies] in the value of an American commitment.” Richard Nixon believed he had to stay in Vietnam because “the cause of peace might not survive the damage that would be done to other nations’ confidence in our reliability.” And John Kennedy was willing to risk nuclear war in the Cuban missile crisis because “for us to fail to respond would throw into question our willingness to respond over Berlin.”39

Beyond credibility concerns, U.S. leaders may be drawn into conflict by an expanding notion of U.S. interests. Allies can take on a value independent of their geopolitical position, thereby leading the United States to protect their survival. Unfortunately, once Washington is committed to treating the security of other states as a core value, those states gain leverage over American policy. A local revisionist can credibly threaten to bear costs and risks on issues it cares deeply about, even if the United States abandons it. If the United States does not believe it can abandon its allies, it will be left adjusting its own policy to absorb the costs and risks of allied revisionism. The Cold War provides abundant examples of that danger. Because the American project in Europe was so dependent on France, the United States ended up taking on most of the costs of France’s colonial war in Indochina. Once Indochina fell, the United States began to value South Vietnam as a bulwark of anti‐ communism in the region. That attitude led to increasing support of the regime in Saigon, even though it thwarted American efforts aimed at internal reform that might have strengthened its hold on power.40

Similarly, American leaders came to value Chiang Kai-shek’s regime in Taiwan for anti‐ communist purposes. But that valuation meant the United States was married to Chiang’s revisionist aims against the Chinese mainland. Chiang would not accept the easy solution of declaring independence and accepting American protection. The result was a series of hair‐ raising crises in the Taiwan Strait, with the Americans breaking Chinese blockades against offshore islands controlled by Chiang very close to the mainland, issuing nuclear threats, and relying on contingency plans based on nuclear attacks deep into China. Those islands had no military value, but they held political value for Chiang, whose domestic legitimacy depended on his claim to rule China. He refused to abandon them even after Chinese pressure stopped, leaving the United States in the awkward and dangerous position of threatening nuclear war to defend several worthless hunks of rock.41 The history of those confrontations has special resonance today, given the prominence of disputes between China and its neighbors over maritime rock formations of no more military value than those defended by Chiang.42

The importance that anti‐ communist regimes took on in materially unimportant places points to another kind of interest expansion to which America is prone: the adoption of ambitious liberal goals. A large literature has developed in recent years endorsing the conclusion that liberal ideas play an important role in driving U.S. grand strategy.43 Ikenberry himself defends U.S. postwar strategy as motivated by the very “milieu” goals that primacists caution us to be wary of in other states.44 It seems reasonable to conclude that a liberal state will not always act like a prudent competition‐ reducing hegemon, but it may find ways to use its vast commitments as platforms for spreading liberal values. No doubt, a liberal state will always face such temptations, but those temptations are much easier to yield to under a primacy strategy that manages security politics in several regions.

A final type of interest expansion is according the proliferation of nuclear weapons an outsized importance in American policy. Such proliferation poses very few dangers to the United States, especially if it occurs among rich states in Asia. If revisionists do appear in Asia, proliferation incentives may increase. But primacy regards nuclear proliferation as a great evil. If proliferation cannot be deterred, wars of counterproliferation might be warranted to nip it in the bud.45 It is no coincidence that the disaster in Iraq was sold on just such grounds and that a prospective war on Iran shares the same logic.46 Because one of primacy’s central benefits is to forestall the dangers of further nuclearization, accepting wars of counterproliferation would seem to be strongly implied by the strategy.47

In sum, there is ample reason to believe that the United States could be drawn into unnecessary conflicts if revisionist powers emerge on the scene. Washington has historically been obsessed with the credibility of its commitments, and primacy is a strategy for which credibility is essential. America has also tended to expand its commitments beyond traditional material interests, treating allies as an independent source of value. Its liberal aims have often driven ambitious foreign policy, and primacy gives liberalism greater scope. Finally, nuclear proliferation is likely to receive inordinate attention from American policymakers, even though it has little effect on American security vis‐ à‐ vis nation‐ states.

Conclusion

The United States faces very few security threats from nation‐ states. The era of potential hegemons has passed: no state is going to conquer a region and turn its power against the Western Hemisphere. The contemporary balance of power, a geography of peace, very difficult military tasks, and nuclear weapons make large‐ scale continental conquest impossible. There will be no blockade of the Western Hemisphere and no corresponding transformation of America into a garrison state. Hitler and Stalin still serve as the backdrop to American grand strategy, yet we will never see their likes again.

Such threats as do exist from nation‐ states, Washington brings on itself. America’s primacy strategy ties itself to regional politics in a way that helps little and could be quite dangerous. Managing security relations abroad is either unnecessary, because of the high costs of war, or unlikely to work in the case of highly dedicated revisionist states. But once committed to a strategy of primacy, policymakers will probably not shy away from the wars they fail to prevent. Primacy will only further stoke the longtime American obsession with credibility, as the strategy hinges on widespread beliefs that America will protect the status quo. Political relationships will tend to take on a value of their own, whether or not they are worth defending. And a powerful America committed abroad will be prone to adventures that have little to do with its security.

To put the point sharply: the United States spends hundreds of billions of dollars a year—and risks war—largely to stop other people from fighting among themselves. The common story that reducing regional competition abroad makes America more secure at home is close to being backwards. The United States is tremendously safe; ill‐ considered decisions to let its alliances lead it into unnecessary foreign conflicts are the only threat Washington faces from states. Politics among nations may well still have some danger, but it is dangerous to America only by its own choice.

The domestic costs of primacy pose a danger of their own. The U.S. defense budget currently sits at nearly $600 billion a year, or around 3.7 percent of GDP. The last time the United States faced so few threats from abroad, in the 1920s, defense spending was about 1.5 percent of GDP. “National security” is massively overproduced in the United States, which represents a tremendous loss of welfare for the American people. Taxes, including those that fund the military, represent a restriction on domestic liberty. In the very short future, the United States will have to manage a major fiscal crunch: the soaring costs of entitlements, a burgeoning welfare state, and the mounting pressure of large debts will all compete for resources. It is difficult to see why a bloated military budget that not only fails to contribute to American security, but also actively detracts from it, ought to be given priority in the coming budget reckoning.

Primacy has also led to a large growth in the national security state and the culture that surrounds it. Civil liberties are gradually taking a backseat to security concerns, as the recent National Security Agency scandals show. Many more elements of policy are being shrouded in secrecy. When policy cannot be debated, the conflictual politics counted on by the Framers to defend liberty and democracy are impossible. The national security state has strengthened the executive vis‐ à‐ vis the legislature, further throwing America’s constitutional structure out of alignment.

The United States is a very rich country, and no domestic totalitarianism is around the corner. Primacy can probably be pursued indefinitely. Before those in the national security class resolve to do so, however, it would be nice if they explained their argument clearly to the American people. The public might not care. But it should.

- By Gus Leonisky at 4 Feb 2023 - 6:52am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

chosen by their gods....

The European Union is organizing a conference entitled: "Beyond disinformation – EU responses to the threat of foreign information manipulation."

Its main thrust is to seek ways of expunging any trace of a Russia-friendly outlook within the Union.

The EU has already censored Russia Today TV channels and the Sputnik agency. It is now extending its reach to EU citizens relaying content from these portals, whether they agree with it or not.

The event will be chaired by Josep Borrell, High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, assisted by Stefano Sannino, Secretary General of the European External Action Service,.

MEP Raphaël Glucksmann, Chairman of the European Parliament’s Special Committee on Foreign Interference, will address the meeting along with representatives of the Swedish Psychological Defense Agency, the British Foreign Office and the US State Department, and of course of NATO.

The star of the show will be Nina Jankowicz, who, after serving as communications adviser to President Volodymr Zelensky, was appointed by President Joe Biden to chair the Disinformation Governance Board, the short-lived US censorship structure.

With the exception of Mr. Glucksman, all the speakers are senior, though unelected, officials.

READ MORE:

https://www.voltairenet.org/article218764.html

THE EMPIRE IS FRETTING....

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....