Search

Recent comments

- peacemonger....

37 min 54 sec ago - see also:

9 hours 38 min ago - calculus....

9 hours 52 min ago - UNAC/UHCP...

14 hours 33 min ago - crafty lingo....

15 hours 57 min ago - off food....

16 hours 6 min ago - lies of empire...

17 hours 6 min ago - no peace....

18 hours 13 min ago - berlinade....

18 hours 38 min ago - difficult...

20 hours 14 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a rotten penny makes rotten pounds....

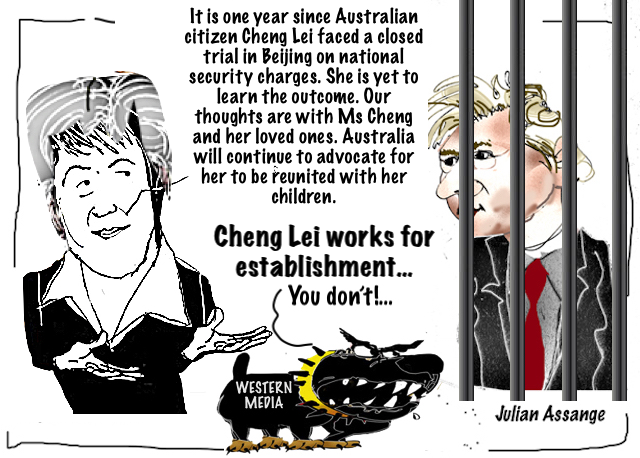

Why is Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong vocal about Australian-Chinese journalist Cheng Lei, jailed in China, but silent on Australian journalist Julian Assange, jailed in the UK?

Senator Wong tweeted on 31 March 2023, “It is one year since Australian citizen Cheng Lei faced a closed trial in Beijing on national security charges. She is yet to learn the outcome. Our thoughts are with Ms Cheng and her loved ones. Australia will continue to advocate for her to be reunited with her children.”

A quick search of Senator Wong’s Twitter feed reveals that since Cheng Lei, a dual citizen of China and Australia, was arrested in August 2020, and charged six months later with “illegally supplying state secrets overseas”, Wong has been a consistent advocate for the former (Chinese state broadcaster) CGTN anchor.

On 25 June 2022, Senator Wong, newly sworn in as foreign minister, tweeted: “Our thoughts are with Cheng Lei—especially today on her birthday. Our hearts go out to her children, whose birthday messages will be passed on during a consular visit to her next Wednesday.”

Three months earlier, on 26 March 2022 then shadow foreign minister Wong tweeted, in response to an ABC article reporting Cheng Lei faces up to life in prison: “This is a deeply troubling development. We join the Government in raising concerns about the treatment of Cheng Lei. We expect Beijing to adhere to its consular obligations to Australia and uphold basic standards of justice.”

On 13 August 2021 Senator Wong tweeted an image of this statement: “Today marks 12 months since Australian journalist Cheng Lei was detained in China. Our thoughts are with Ms Cheng, her friends and family–particularly her two children. Labor holds serious concerns about Ms Cheng’s detention and her welfare. We support efforts to provide Ms Cheng with regular consular assistance, as well as ongoing assistance for her family. Labor joins the Government in calling for acceptable standards of justice, procedural fairness and humane treatment to be met, in accordance with international norms.” (Emphasis added.)

And on 8 February 2021, six months after Cheng Lei’s arrest: “Our thoughts are with Cheng Lei and her loved ones following confirmation of her arrest. We support efforts to provide Ms Cheng with consular assistance and join the Government in calling for acceptable standards of justice, procedural fairness and humane treatment to be met.”

Contrast Senator Wong’s consistent, vocal advocacy for Cheng Lei, with her tweets about Australian Walkley-award winning journalist Julian Assange, jailed in the UK’s maximum security Belmarsh Prison since April 2019—15 months earlier than Cheng Lei’s arrest:

There are none—not once has Senator Wong tweeted about Julian Assange.

Senator Wong does talk about Assange, but only ever in response to questions, such as Greens Senator David Shoebridge asked in Question Time on 31 March, to which she reiterated “the government’s view that Mr Assange’s case has dragged on too long, and should be brought to a close”.

However, former Senator Rex Patrick has revealed through Freedom of Information requests there is zero documentation showing any formal advocacy from the Albanese government to the UK and US governments expressing this “view”.

Imagine if Senator Wong as shadow foreign minister and now foreign minister was as vocal in support of Assange as she has been of Cheng Lei.

At his National Press Club appearance on 15 March, former PM Paul Keating sized up Senator Wong’s modus operandi on foreign policy, which helps explain her double standards on Assange:

“Penny Wong took a decision in 2016, five years before AUKUS, not to be at odds with the Coalition on foreign policy on any core issue”, Keating said. “You cannot get into controversy as the foreign spokesperson for the Labor Party if you adopt the foreign policy of the Liberal Party… You may stay out of trouble, but you are compromised. Self-compromised.”

Under the previous Liberal government, China-bashing became a popular pastime, while Julian Assange was treated as a pariah, in keeping with the attitude of the US national security establishment.

On both issues, Labor has sounded mixed signals, but fundamentally maintained the Liberals’ pro-US (and UK) positions.

The truth about Cheng Lei is unknown, but Assange’s status is known—he’s a publisher who’s innocent of the espionage charges against him.

A foreign minister of a sovereign government would advocate vocally for both.

READ MORE:

https://johnmenadue.com/penny-wongs-double-standards/

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Apr 2023 - 5:44am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

we, the annoying people......

For a public servant of my acquaintance, the new and emerging problem of public administration is dealing with what she called activists and advocates.

Apparently, it was not a problem, or as much of a problem, before as it is now. Now it threatens good government. And she’s not talking about the unnatural influence on government and bureaucrats of rich and powerful corporations and business. She’s worried instead about the obstacles placed in their way by busybodies, small community organisations, and people with no particular right to be heard on particular subjects. Like animal rights activists on agricultural practices, trade unionists on banking culture, or non-warriors on war memorials. The best efforts of politicians – including the reining-in of rights once granted – have not stopped troublemakers meddling in the domains of others, including the bureaucracy.

It’s something, apparently, politicians and public officials must do something about. So as by stripping legal and social appeal rights. By killing off bodies once established to promote and protect private interests. Reducing public expectations of the right of people to be involved in decision making. By removing “unnecessary” regulation, process and potential blockages open to abuse by naysayers to projects creating employment, facilities and economic opportunities for the community.

She’s typical of a new breed of public servant impatient and dismissive of consultation – seeing it at most as being a public relations gesture before doing what has already been determined and decided. Suspicious of the self-interest of citizens, but amazingly willing to take as read the obvious self-interest of the people she calls stakeholders. Stakeholders are businesses and big vested interests of whose needs one must be aware. Stakeholders are never, of course, ordinary citizens. Not the unemployed, the sick, the disabled, single mothers or students. Stakeholders are employers, (sometimes) unions, healthcare lobbies, service providers and educational establishments.

The Albanese government has the right to claim that it is running a far more regular and accountable government than its predecessor. Most of its ministers are well educated in the needs of the community and the needs of the stakeholders. They may be trying to reduce the government’s dependence on external consultants. And its ministers, particularly its Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, are given to setting up at least one new fresh inquiry or review into the protection of some public interest or another every day. One might almost think that we were back to a time when the law and the courts were in favour of the little guy. Against big government, as over robo-debt. Or centralised bossy government, as over welfare benefits or pre-Voice Indigenous affairs. Or corrupted review processes, as with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. Or protecting people who expose abuses of public power or even murder. Or government departments who actively and consciously abuse the human rights of vulnerable people.

Yet somehow there’s a lot more talk than action when it comes to citizen participation in government. Or accountable government. Or the rights of activists and advocates – now, for the purpose of the exercise tending to be regarded as Greens, or Teals, or other people who might hold back the government from what it wants to do.

The FOI Act is being abused by ministers and bureaucrats, from the prime minister and his department down, as much as it was by the Morrison government. Despite talk of reviewing the FOI Act, Dreyfus, by depriving the Information Commissioner of resources has ensured that there is no effective appeal against refusal. The Information Commissioner has resigned from frustration. Despite the talk of stronger whistle-blower legislation, Dreyfus is too timid to protect two clear public heroes who have exposed abuses of government power – in one case over war crimes, in another over improper tactics by the Tax office. And the champion of universal human rights is astonishingly indifferent to the official and consciously cruel maltreatment of boat people.

Other ministers and their bureaucrats have proven far keener on their own, often well-intentioned, views of the best thing to do than asking the public, or the “clients” what they think. They may not be enthusiastically doling out jobs and money to their mates, cronies, and party donors in the manner of some Morrison-era ministers. But they are no more inclined to listen to the public, or to groups with developed criticisms of past policies and ideas about how things could be improved. While selling the virtues of the Voice they are making cogent criticisms of decades in which ministers and bureaucrats knew what was best for Indigenous Australians. But they have no more reformed their current consultation and delivery systems in Aboriginal affairs (which is to say prime minister and cabinet) than they have reformed the philosophy of public consultation, citizen participation, or transparent government in any of the other million functions of government. For too many ministers, minders, and administrators, “activist” is still a term of abuse.

Top administrators are very attentive to their stakeholders. But they run a mile from ordinary citizens.

This new breed is very efficient and professional in dealing with “stakeholders” – the big operators getting the money, the rights, or the attention to their needs. They are experts on the provider groups, often knowing their industries so well they can easily move later into being consultants to them, or lobbyists for them. It’s not necessarily the prospect of that future that guides them: It’s often absorbing where they are now, seeing the action as from a nearby hill, rather than in the smoke of battle. She is not their creature and has robust views about where the public interest lies. But she’s not keen on taking external advice about it, or of being accused of governing in their interests. You must trust her.

But she admits she finds it difficult to deal with busybodies, and doesn’t see why she should. Or journalists and outside “pressure groups” demanding information about the relationships between government and the stakeholders – sometimes indeed intrinsically confidential financial or contractual information with the capacity to embarrass both buyers and sellers. These people do not have entrée into the inner sanctum. The sworn common enemy of both the departmental manager and the stakeholder is the sort of person, or group, who thinks that the business of government can or should be conducted in a goldfish bowl, without mutual confidence or trust between parties, and without that room for discretion so often essential for win-win arrangements.

Activists are seen as usually hostile to the project in view, as often as not from some oblique angle. They are not engaged in a legitimate search for the best place to conduct mining or situate a railway line. They just don’t want mining, or the railway at all. They are not interested in the best place to locate public housing or a jail, except from the perspective of having it as far away from their homes as possible. They have no personal interests or property rights needing to be taken into account in relation to the treatment of asylum seekers, or prisoners, the conservation of some threatened species, or the threat from climate change. Their intellectual, aesthetic, cultural or emotional opinions can be acknowledged, even up to a point respected. But their having a point of view does not give them the right to interfere, to frustrate worthy projects, or to diminish or limit the value of assets of other taxpaying citizens or companies. Their assertions about the relevant facts, the weight and importance of the relevant considerations, and about facts they insisted should be taken into account were often contestable. And self-interested. But they act as if their interests are legal rights and in fact as important as those who were investing money, or making choices about the best disposition of public resources. Often too they were insisting on attention to “evidence” when the real decision was one of principle.

Likewise with the expectations that some people had that they would be consulted about every proposal for action which could affect them, with any decision or action suspended or forbidden until those being consulted agreed with what was proposed. Consultation might serve some purposes, such as getting at least the grudging assent of the neighbours or some recognition of public policy choices being made. But a commitment to consultation was not a commitment to endless public meetings, let alone discussions in which the experience, professionalism and integrity of officials was put in contest, or in which the sensible and objective working assumptions of impartial experts were questioned and disputed. All that was necessary for consultation was a right to make a submission, which might not even be read. The fact that some proposals might cause some inconvenience or pain to a small group of people without real legal rights should not be allowed to stand in the way of achieving the greater good for the greater number of interests in the community.

To such people the practical merits of “rights” such as Freedom of Information legislation are much exaggerated. Particularly when one takes account of the time and the energy, and the distraction caused to officials by processing claims. Since many claims, including by journalists, are filed by people without any legal interest in the outcome of whatever decision was involved, and others come from groups with an active agenda of frustrating the policy, proposal or program in question, one can hardly be surprised that officials would resist disclosure, which was bound to cause trouble.

Ministers and senior officials might pay rhetorical lip service to the benefits of open government, transparency and accountability. But they rarely criticise a slow, grudging and highly legalistic approach to processing claims, and the refusal of as much information as possible. And, given the designed slowness of the appeal system, one could at the least postpone the provision of information until it was old news, no longer controversial or where the major players were now off the scene. It was much the same in estimates committees, where senior officials played games with senators (wink wink) about how little information could be disclosed, and how little help or explanation volunteered. But those inclined to purse their lips should understand that the whole system of estimates was an unnecessary farce, without any sort of parallels in modern industry, and that preparing for and appearing in estimates was a major distraction from more important matters of state. Indeed, all too often for no purpose, since senators would often have all the senior officials waiting around for hours before sending them home without having asked a question of any significance or importance, particularly by comparison with the budget an agency controlled or managed.

Their feeling that a good many of the processes of government are cumbersome and inefficient is real enough. And widely held in the public service. There are, indeed, people and groups adept at playing the system against itself to slow or defeat proposed government action. But they under-estimate the value and importance of the consent of the governed, and the costs of not getting it. Yet all too often, those expressing frustration at the delays caused by process and consultation tend to regard the obstruction and resistance of the powerful lobbies as legitimate and natural – even sometimes admirable even when there are clear social costs. By contrast, the legitimacy of consumer, citizen or social objection, even one advanced by politicians, is seen as representing a defeat for their system, perhaps for being emotional and not strictly economically rational.

‘Activist’ has become a modern term of abuse. Modern government is about freezing them out and denying them platforms.

The very word “activist” is now a term of abuse in government. It was once somewhat of a badge of honour, suggesting citizens who took an active and public-spirited interest in the welfare of their communities by joining worthy groups and associations seeking improved services and outcomes for the broader community. It was community activism – as someone reminded a public meeting I attended the other day – that gave us the National Trust, heritage legislation, and most of our general environmental protections. It was citizen activism – including the unwelcome ideas of busybodies – that saw the abolition of slavery and, in Australia, the abolition of transportation, women’s suffrage, the eight-hour day, and human rights for homosexuals. It was, usually, just the same citizens active on political fronts and seeking to advance (or frustrate) personal rights and public freedoms and rights, who were also the most active in community social, cultural, sporting, and welfare groups. They were the backbone of the community and the engine-room of much of its economic activity. It was simply too easy to describe them as NIMBYs, NOTEs, or BANANAs, or to see their concern for the general welfare as malign and destructive of personal property rights.

Many of the major reforms of government grew from popular movements and the activism of ordinary Australians. Does anyone imagine that the development in the rights of women from the 1970s came because of public service initiatives? Actually, up to a point they did, but only because a generation of able and dedicated women entered government and public administration from outside, with the active encouragement of people such as Gough Whitlam, Susan Ryan and others, to promote a rights agenda. Most law reform, including the Ombudsman, judicial and administrative review and FOI, occurred against the resistance of an old bureaucracy which distrusted innovation and accountability. Successive Attorneys-General, such as Lionel Murphy, Kep Enderby and Peter Durack were associated with enormous law reform. But the then head of Attorney-General’s, Sir Clarry Harders, running a far more talented department than today, often boasted that no policy ideas ever came from his bureaucrats. His department, he said, was merely the empty vessel into which policy was poured by ministers. Their genius was in implementing the ideas of their ministers.

Those were days, moreover, in which genuine and well-thought ideas often came to government from work inside branches of political parties. Australian political parties, on all sides, have always been centres of intrigue, faction and mindless ideology. But there was a time in which members had power within their party, and where ideas were raised, debated and converted into party programs and policy. Now that work, on both sides of politics, has been taken over by a professional party bureaucracy and minders, most of whom have never worked outside politics, and party conferences are choreographed so as to avoid any actual debate. Active participative membership of parties is at an all-time low.

The funny thing is that ICT developments over the past 50 years have made the business of interchange between the governed and the governors far more easy. But for all of the theoretical capacities of the new toys, the practical effect has been to widen the differences and make mutual understanding less likely. Many of our communications are into the ether, shouting at each other, rather than discussions with particular people. Business might have adopted online meetings but this does not happen so much in the development of public policy.

For many, the world is now a more hostile place from the moment one walks out the front door. People are less likely to join clubs and associations, whether for sport, politics, culture or recreation. People, rightly, distrust the media and other forms of public information-sharing, including social media and the spin of politicians. The number of real journalists is about a fifth of what it was forty years ago; the numbers of paid public relations people, marketeers, “spokespeople” and other professional spin-doctors and liars has increased by about 600 per cent.

It is into this vacuum, this abyss, that self-confident politicians, bureaucrats and consultants come to know and believe that they know more about what people really want or need than the people themselves. That’s one of the reasons why they are especially resistant to the idea of listening to ordinary folk with an active interest in the subject. If these new professionals ever need to check their sense of reality, a short opinion poll, as often as not slanted, will save them the bother of actually asking ordinary people. Or listening. Or negotiating. Pretty soon, I expect, our best and our brightest public servants will be as alienated from the community – and the community from them — as in the US.

READ MORE:

READ FROM TOP.

WE OLD FOLKS MIGHT NOT GO IN THE STREETS TO PROTEST ANYMORE, BUT WE STILL PUSH THE BARROW OF WHAT IS WRONG WITH THE "ESTABLISHMENT"....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

our prison....

Reporters Without Borders representatives were turned away for “spurious reasons,” its director has claimedTwo senior members of Reporters Without Borders (RSF) have been barred from seeing WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange at a London prison despite having prior approval to visit him, the organization has claimed.

In a statement on Tuesday, RSF said Secretary General Christophe Deloire and Director of Operations Rebecca Vincent had not been allowed to enter Belmarsh Prison, “despite having been vetted in advance and receiving confirmation.”

RSF, which is an international non-profit organization that seeks to safeguard the right to freedom of information, said that the activists had wanted to assess the conditions that Assange is being kept in and to speak with him about his case. It added, however, that Assange’s wife, Stella, had been allowed to see her husband.

RSF said prison officials claimed to have “received intelligence” that the activists were in fact journalists, meaning they were not allowed to enter. Deloire criticized the “arbitrary” decision, arguing it was made “for a spurious reason” at the last minute.

The organization claimed that the pair had been attempting to visit the WikiLeaks co-founder not as journalists, but rather as NGO members.

Vincent stated that “at every level, British authorities have defaulted to secrecy and exclusion rather than allowing normal engagement around this case… What do they have to hide? Regardless, we continue our campaign to #FreeAssange unabated.”

Assange, an Australian-born publisher, has been a target for the US since 2010, when WikiLeaks released a trove of classified documents revealing alleged war crimes committed by US forces during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is accused of conspiring to hack Pentagon computers and has been charged under America’s 1917 Espionage Act over the publication of classified materials.

From 2012 to 2019, Assange took refuge at the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. After his asylum status was revoked by Ecuador’s government, Assange was transferred to the maximum-security Belmarsh Prison. A legal battle is ongoing over his potential extradition from Britain to the US, where he is facing a prison sentence of up to 175 years.

READ MORE:

https://www.rt.com/news/574163-assange-prison-visit-ban/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

spanish julian?....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCWzC3qvTnE

Is Zelensky's government in Ukraine targeting journalists in Spain for revealing the truth about the war? Ruben Gisbert is a Spanish journalist who has been covering the Donbas and has been doing some excellent reporting. But telling the truth is a bridge too far and now he's under investigation by the attorney general of Spain after a phone call from the Ukrainian government.

Ruben Gisbert es un abogado que se dedica a la divulgación política, su objetivo es difundir los principios de la ciencia política que estructuran e instituyen la democracia formal, las ideas de la libertad política colectiva.

NOW:

Poland: Spanish journalist Pablo González in custody for one year on charges of spying for Russia and no trial in sightA Polish court extended Pablo González’s pre-trial detention for the fourth time on 15 February 2023, meaning he will spend up to a further three months in prison. The Spanish freelance journalist was arrested on 28 February 2022, accused of being “an agent of Russian intelligence”, while covering the humanitarian crisis on the Polish-Ukrainian border. The International and European Federations of Journalists (IFJ-EFJ) and their Spanish affiliates call on the authorities to release González without further delay, and ensure he will receive a fair trial.

“The case is still in the Prosecutor's Office. This is an investigation, and it is not known how long it will take. In Poland, investigations in large cases take up to several years,” his Polish lawyer, Bartosz Rogała said. “In my opinion, the case will go to the Court at the earliest in the middle of this year,” he adds.

“There are no maximum terms for detention in Poland,” Mr Rogala noted. “Pre-trial detention, even for several years, is common in large cases. If someone is from abroad, the Court often recognizes that there is a fear of escape, which is one of the reasons for arrest,” the lawyer concluded.

The journalist’s defence has appealed against each decision of the court to extend pre-trial detention. Until today, there is no trial date in sight, nor has the evidence against him been made public.

In the early hours of 28 February 2022, González was arrested by agents of the Internal Security Agency (ABW), the Polish counter-intelligence service, on the Polish-Ukrainian border, where he was reporting on the humanitarian crisis, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Polish authorities alleged that the reporter, who holds Spanish and Russian nationality, had been in possession of two passports with different names. The issue was quickly clarified as González’s Russian passport identifies him as Pavel Rubtsov, using his father’s surname; and his Spanish document as Pablo González Yagüe, using his mother’s two surnames.

On 8 March 2022, the IFJ and the EFJ submitted an alert to the Council of Europe Platform for the Protection of Journalism, which has not been replied to by Polish authorities.

In September 2022, González submitted a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights for violation of his rights and, in particular, for his classification as a ‘dangerous prisoner’. Although he is no longer classified as such, the reporter remains in the same department of the Polish penitentiary system for dangerous prisoners, meaning that he is isolated 23 hours per day, remains handcuffed when leaving his cell, and is placed under strict monitoring.

The Association #FreePabloGonzález, created by his family and friends, has denounced the lack of transparency and information around the case. “Communication with him is very limited. It takes around three months for his letters to arrive from Poland to Spain. His wife and mother of his children, Oihana Goiriena, was allowed to visit him for the first time at the end of November, after 9 months in jail,” explained his close friend and spokesperson of the association, Juan Teixeira. “No other journalist in the European Union is detained in another member state under such conditions.”

González, who specialises in the post-Soviet world, was a regular contributor to the Spanish daily Público and was reporting on the humanitarian crisis on the Polish-Ukrainian border for several Spanish media outlets, including La Sexta.

"The release of Pablo González is an ethical requirement, especially in an EU country that supposedly defends freedom of expression,” said Miguel Ángel Noceda, President of the Federation of Spanish Journalists’ Associations (FAPE). “We demand once again that the Polish authorities resolve the situation with the maximum legal guarantees and in favour of the Spanish journalist after a year of obscurantism," he adds.

The Federation of Citizen's Services of Comissiones Obreras(FSC-CCOO)said:“It is unacceptable for a state to detain a journalist in such an arbitrary manner and we therefore urge both the Spanish State and the EU to do everything in their power to put an end to this injustice once and for all. [...] A state that does not guarantee freedom of the press and the safety of journalists cannot be considered a true democracy.”

Agustín Yanel, Secretary General of The Federation of Journalists' Trade unions(FeSP) declared: "It is unheard of and totally reprehensible that an EU Member State that claims to be democratic should keep Pablo González in prison for a year, without trial and without respecting the most elementary rights that any detained person should have”.

“The Polish authorities must release him provisionally as a matter of urgency and guarantee that he will receive a fair trial with guarantees,” he added.

The Association of Journalists in Spain (UGT) insisted that it is unacceptable that a government that claims to be democratic can keep a prisoner in custody for a year. “We call for the immediate release of Pablo González and for him to be tried with all the guarantees and with the consular support of the Spanish Government”.

In a joint statement, the IFJ and EFJ have renewed their calls on the Polish government to release González without further delay. “It is unacceptable for a member state of the European Union to detain a journalist in such an arbitrary manner. It is an attack on media freedom and democracy.”

For more information, please contact IFJ on +32 2 235 22 16

The IFJ represents more than 600,000 journalists in 146 countries

https://www.ifj.org/media-centre/news/detail/article/poland-spanish-journalist-pablo-gonzalez-in-custody-for-one-year-on-charges-of-spying-for-russia-an.html

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....