Search

Recent comments

- sicko....

9 hours 1 min ago - brink...

9 hours 17 min ago - gigafactory.....

11 hours 4 min ago - military heat....

11 hours 46 min ago - arseholic....

16 hours 30 min ago - cruelty....

17 hours 46 min ago - japan's gas....

18 hours 27 min ago - peacemonger....

19 hours 24 min ago - see also:

1 day 4 hours ago - calculus....

1 day 4 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

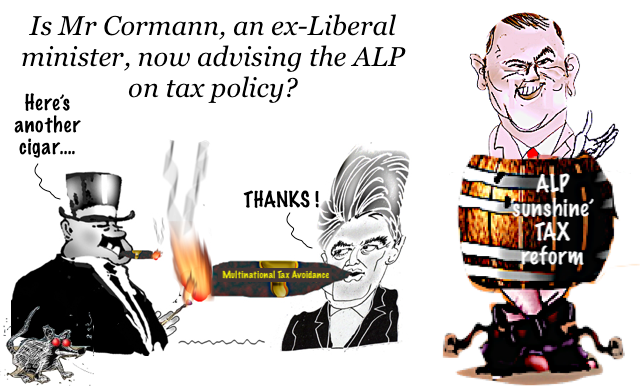

another barrel of red herrings......

Multinational tax avoiders and the OECD have won a reprieve from the Albanese government which has delayed legislation aimed at shining the light on tax avoidance. Jason Ward explains why the backdown is bad news.

The Labor government made an election promise, a budget promise, a legislative promise and held two consultations on landmark legislation to implement global tax transparency for multinationals. Now it has bent to corporate pressure. Landmark legislation for public country by country reporting was set to be implemented as of 1 July.

Late last week, it was announced that implementation will be pushed back for at least a year.

by Jason Ward

The question remains whether this is a genuine delay for further consultation or whether this is the beginning of a more complete capitulation to corporate interests. One might ask why the Labor government continues to heed the advice of PwC, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft and the Corporate Tax Association (whose members include Accenture, ALDI, Amazon, Brookfield, Chevron, Coca-Cola, Exxon, Glencore, Google, Lendlease and News Corp, just to mention a few upstanding corporate taxpayers)?

Sunshine is best disinfectantThis measure was not directly raising taxes. But it was mandated tax transparency for all large multinationals operating in Australia. It would have required all multinationals with operations in Australia to provide basic public financial information for every country where it has a presence.It could lead to increased revenues desperately needed to fund our underpaid and overworked, teachers, nurses, aged care workers and many other public service workers. It would level the playing field for the vast majority of businesses that don’t create complex corporate structures to shift profits to tax havens and avoid domestic obligations.

It would have let the sunlight into the murky world of multinational transfer pricing which now makes up the bulk of global trade.

However, there are powerful advocates to keep us all in the dark and sadly it seems the Labor government has listened. As Mark Zirnsak, from the Tax Justice Network Australia says, there has been significant blow-back by the business lobby over the ambition or scope of country by country reforms. “Our understanding is that there was robust lobbying against it. There is disappointment on our side that it might be walked back to something more acceptable for business – but I think the reform is very much in play.”

Others are not so sure. Successive governments have delayed money-laundering laws for 16 years, under pressure from the property, lawyers and accountants lobby (AML-CTF Tranche II).

Push for transparency gathers paceEarlier this month, one-third of independent shareholders at Brookfield – the global giant asset manager that is poised for a $19 billion takeover of Origin Energy, to add to its existing stable of Australian assets, including AusNet, Healthscope, Aveo, Multiplex and more – voted to require the company to implement public country-by-country reporting.

If shareholders, including some of the world’s largest investors, are asking for transparency, how is it that the Australian government would bend to the will of corporate executives and their lobby groups? Increasingly, many multinationals are voluntarily providing public country-by-country reporting following the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) Tax Standard, upon which the Australian legislation is based.

A similar version of this information is already provided confidentially to tax authorities in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development) member states. Some tax authorities may use this information effectively, but some may not; we don’t know.

Tax authorities in the global south, most reliant on corporate income tax and least able to collect, have no access to this information. Australia’s legislation would make the data public for all to see and use to hold multinationals to account or make them be less dodgy.

Is Mathias Cormann still in government?The OECD, now led by Australia’s former Finance Minister Mathias Cormann, is known to prefer multilateral approaches to combating tax avoidance. His organisation’s opposition to corporate tax transparency is also well known. Is Mr Cormann, an ex-Liberal minister, now advising the ALP on tax policy?

Corporate interest already lobbied hard and succeeded in watering down the European Union’s (EU) effort at country-by-country reporting. The forthcoming EU rules, not yet implemented, only require reporting on tax and other financial information in EU member states.

The rest of the world – including Australia, the US, the UK, China and India (to name a few) – would be reported as a lump sum. There would be no way to see where else in the world profits may have been shifted.

In fact, the EU effort might create perverse incentives to shift tax dodging schemes from Ireland and Luxembourg to Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Singapore or many others. The small Pacific Island nations of American Samoa, Fiji, Guam, Marshall Islands, Palau, Samoa & Vanuatu – with limited lobbying power in the EU – are 7 of the 16 jurisdictions in the EU’s deeply flawed ‘tax haven blacklist’ for which disclosure would actually be required.

This information should be public so that shareholders, academics, civil society, and the general public – if they care to look – could see how complex corporate structures are used to shift profits to avoid tax obligations.

Nothing happening, nothing to hide, right?In Australia, we already have limited data on tax payments by large companies, but this does not show us what profits might be shifted where. When this data has been available, as it has been for banks in Europe since 2014 (who, by the way, are still doing pretty well) it reveals that profits are being booked in Bermuda, Puerto Rico, Luxembourg and Singapore, where there is little, if any, genuine economic activity and little to no taxes paid.

That’s the recipe for the ‘special sauce’ that multinationals don’t want revealed. Let’s hope the Labor government does live up to its promise of mandating transparency and lets the sunshine in, otherwise we will all continue to be in the dark.

READ MORE:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Jun 2023 - 11:01am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

one dollar....

by Michael West

What’s the scam with PwC flogging its government consulting operation to private equity mob Allegro Funds Management?

The scam is that the scandal over selling government secrets has hurt PwC in a real way, there is pressure from the global partners over to exit to rehabilitate the brand, and they have found some private equity turnaround players in Allegro who will take on the risk of salvaging that $300m a year in government contracts.

Does this include state government consulting work? Probably not as the Big 4 write more than a billion a year in business consulting to governments. We don’t know yet though and state procurement disclosures are foggy at best, non-existent at worse.

This from a corporate lawyer:

“There are always offshore intervention rights under the brand licensing agreement – to protect the brand – does not mean control, just a threat of intervention and loss of the brand. PwC Global would have the right to terminate Aust’s use of the brand under enumerated conditions, including material compliance with a list of standards.

“There would have been termination procedures if brand use was withdrawn or modified. Everyone would have been reading these over the last few months – and the local partners would then start to fight amongst themselves as to how this might operate in this case. This takes time to sink in – then acceptance gradually takes over before depression sets in.

“I suspect that PwC global threatened to withdraw the brand permission for the Gov’t business. There would be numerous legal opinions about this circulating in Sydney London and NewYork.

“Allegro then looked at taking govt off their hands and demanded a sweetener – that PwC throw in the risk business too – to enhance the package. It’s a useful adjunct for Allegra to add to Slater and Gordon. Expect them to build this portfolio.”

Allegro has no expertise in government consulting, they are “turnaround” merchants having a punt to salvage some value. It is unlikely there would be earn-outs or kickbacks to PwC as the government would surely check this. The global PwC partnership has just said “get us out of this!”.

So the scandal has taken a huge toll on the firm already – government consulting was the fast-growth element which has delivered double digit revenue returns for the Big 4 in recent years.

Now to the meaty bit. The next Senate inquiry is into the secretive partnership structures of the Big 4 and will no doubt go to the guts of the problem that they are just too powerful, too opaque and too conflicted.

READ MORE:

https://michaelwest.com.au/pwc-sells-government-consulting-operation-for-a-dollar-whats-the-scam/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........

sold the farm...

Australian companies worth billions of dollars are slipping into private hands at an alarming rate. Stephen Mayne explores what’s driving it and why it’s a worry.

After 38 years as a public company, vitamins group Blackmores this week fell into Japanese hands when more than 96.85% of voting stock supported Kirin’s attractive $95 a share $1.8 billion takeover bid.

Sadly, this isn’t a new phenomenon. The past four years has delivered an unprecedented splurge of takeovers of ASX listed companies which has coincided with an unprecedented drought of big floats, leading to a hollowing out of the ASX lists.

The 29 substantial public takeovers completed over this period have included the following ASX listed companies:

Afterpay, ALE Property Group, Ausnet Services, Automotive Holdings, Aveo, Blackmores, Bellamy’s, Bingo, Coca Cola Amatil, Crown Resorts, Dulux, Galaxy Resources, Healthscope, Infigen Energy, CIMIC, Milton, MYOB, Nearmap, Oil Search, OZ Minerals, Pendal, Slater & Gordon, Spark Infrastructure, Sydney Airport, Tassal, Uniti Group, Village Roadshow, Vocus Communications and Western Areas.

List-lessThe total equity value of these companies exceeded $100 billion, as can be seen from this comprehensive but quite shocking list of 163 companies which were once capitalised at more than $1 billion on the ASX but are no longer listed today, whether it be from takeover or collapse.

The ASX admits we’ve got a problem re-stocking the public company shelves. A spokesman said:

IPOs are cyclical and we are at the bottom of the cycle right now. It’s the slowest it’s been in a decade.However, this is not unique to ASX. It’s a global phenomenon as a result of uncertain investor sentiment due to geopolitical issues, but more importantly inflation and the impact on monetary policy – where will rates go and what will be the impact on economies? Compared with our global peers, we do a lot of IPOs, and while numbers are significantly down this year, historically we have listed around 130 new companies annually.

Takeover targetsIn addition to the Blackmores exit, the pipeline of upcoming takeovers is also looking ominous with the following major deals announced but not yet approved by shareholders:

Costa Group: floated by the Costa family and its US private equity partner Paine in 2015 and then Paine has returned with an indicative $1.6 billion offer announced earlier this month.

Invocare: the death industry giant has agreed to an indicative offer by US private equity firm TPG at $13 a share or $2.2 billion in total and we’re just awaiting the completion of due diligence.

Newcrest Mining: the biggest remaining ASX-listed gold miner has signed a binding agreement to be taken over by Denver-based US giant Newmont in an all-scrip offer valued at $29 billion which will go to a vote once the usual 300-page scheme book is finalised.

Origin Energy: signed a 142 page binding agreement way back on March 27 to sell itself for $18.7 billion to Canadian giant Brookfield and its US partner MidOcean Energy for $8.91 a share with a shareholder vote due later this year. This is a bit embarrassing given that the board knocked back BG Group’s $15.50 a share offer way back in August 2008. If you’re going to sell off the farm, at least maximise the price.

United Malt: was only spun out of Graincorp in 2020 but is being snapped up by Soufflet Group, a private French company controlled by the Soufflet family which has offered $5 a share or $1.5 billion in total.

So, what’s left to buy and sell?Once you’ve digested this surprisingly long list of 163 departed $1 billion-plus companies have a look at this list tracking what’s left in the form of the current “top 150 companies” which were listed in The Australian’s weekend edition on Saturday.

At face value, it should be re-assuring that the 150th company, 4WD outfit ARB, has a healthy market capitalisation of $2.49 billion.

However, The Australian’s list is not what it seems.

For starters, it includes ten New Zealand companies, such as Infratil, Auckland Airport, Fisher & Paykel and Meridian Energy. Well, at least their assets aren’t too far away, unlike others on the list such as Zimplats Holdings, which has a big platinum operation in Zimbabwe, or Champion Iron which only operates mines in Quebec.

For some reason, The Australian doesn’t list News Corp, even though it has a secondary listing on the ASX and substantial assets here.

However, The Australian has included six ETFs listed in their top 150, such as the Vanguard Australian Shares Index which comes in at number 40 with a market capitalisation of $12.39 billion. Are ETFs even “companies”? When all they do is invest in other companies or asset classes?

Why this is happening?There are a number of factors behind this hollowing out of the ASX. The first is our general inability to develop successful Australian head-quartered multi-national companies like Computershare, CSL, Macquarie, QBE and Wisetech.

Then there is our open door policy for takeovers, which is arguably more liberal than other country, with the possible exception of the UK. As this list of more than 320 foreign companies turning over $200 million-plus in the Australian market shows, an increasingly large chunk of the Australian economy is foreign-owned.

Big Super on the riseThe next issue is the growing tendency for our big industry super funds to take public companies private. Vocus Communications, Sydney Airport and ALE Property Group were all snapped up by industry funds over the past three years.

Standby for more of this with toll road company Atlas Arteria expecting a bid soon from Industry Funds Management (IFM) which has already amassed a 23% stake on market.

Foreign trade buyers have also been active over the past four years with Nippon Paint buying Dulux, Canadian fish giant Cooke Inc buying Tassal and the French purchase of United Malt.

And then there is private equityHowever, it is private equity which is the biggest driver, having taken out dozens of companies over the years, with many more in prospect.

And imagine if all of their prospective bids had proceeded. Surviving ASX100 companies like Ramsay Healthcare, Treasury Wine Estates and Santos have all rebuffed private equity bids in recent years.\

Too much powerThe final problem is weak competition laws in Australia which have seen far too many takeovers approved, creating excessive domestic market power for the predators.

For instance, Howard Smith traded as a public company for 143 years until Wesfarmers was allowed to buy it for $2.7 billion in 2001. This eliminated its main Bunnings competitor, the BBC hardware chain, and made life hard for the remaining independents. Even Woolworths couldn’t compete with its failed Masters venture.

If you read through the “disappeared companies list” you’ll see countless other examples. For instance, buried inside the privatised Commonwealth Bank is three former state banks – BankWest, State Bank of Victoria and State Bank of NSW – along with former mutual Colonial. No wonder CBA is a super profitable behemoth valued by investors at $170 billion, making it takeover proof forever and a day.

A watchdog regretsIn his farewell February 2022 speech as Australian Competition and Consumer Commission boss, Rod Sims told the National Press Club that he regrets the power imbalance between big and small businesses in Australia, including the plight of farmers battling to get reasonable terms out of supermarket giants.

It’s a problem which is being exacerbated by the current startling run of ASX takeovers and the lack of viable scaled new competitors emerging to compete.

https://michaelwest.com.au/the-sharemarket-of-deathly-hollows-100b-of-equity-passes-from-public-to-private-hands-in-takeover-binge/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........

sold the farm...

Australian companies worth billions of dollars are slipping into private hands at an alarming rate. Stephen Mayne explores what’s driving it and why it’s a worry.

After 38 years as a public company, vitamins group Blackmores this week fell into Japanese hands when more than 96.85% of voting stock supported Kirin’s attractive $95 a share $1.8 billion takeover bid.

Sadly, this isn’t a new phenomenon. The past four years has delivered an unprecedented splurge of takeovers of ASX listed companies which has coincided with an unprecedented drought of big floats, leading to a hollowing out of the ASX lists.

The 29 substantial public takeovers completed over this period have included the following ASX listed companies:

Afterpay, ALE Property Group, Ausnet Services, Automotive Holdings, Aveo, Blackmores, Bellamy’s, Bingo, Coca Cola Amatil, Crown Resorts, Dulux, Galaxy Resources, Healthscope, Infigen Energy, CIMIC, Milton, MYOB, Nearmap, Oil Search, OZ Minerals, Pendal, Slater & Gordon, Spark Infrastructure, Sydney Airport, Tassal, Uniti Group, Village Roadshow, Vocus Communications and Western Areas.

List-lessThe total equity value of these companies exceeded $100 billion, as can be seen from this comprehensive but quite shocking list of 163 companies which were once capitalised at more than $1 billion on the ASX but are no longer listed today, whether it be from takeover or collapse.

The ASX admits we’ve got a problem re-stocking the public company shelves. A spokesman said:

IPOs are cyclical and we are at the bottom of the cycle right now. It’s the slowest it’s been in a decade.However, this is not unique to ASX. It’s a global phenomenon as a result of uncertain investor sentiment due to geopolitical issues, but more importantly inflation and the impact on monetary policy – where will rates go and what will be the impact on economies? Compared with our global peers, we do a lot of IPOs, and while numbers are significantly down this year, historically we have listed around 130 new companies annually.

Takeover targetsIn addition to the Blackmores exit, the pipeline of upcoming takeovers is also looking ominous with the following major deals announced but not yet approved by shareholders:

Costa Group: floated by the Costa family and its US private equity partner Paine in 2015 and then Paine has returned with an indicative $1.6 billion offer announced earlier this month.

Invocare: the death industry giant has agreed to an indicative offer by US private equity firm TPG at $13 a share or $2.2 billion in total and we’re just awaiting the completion of due diligence.

Newcrest Mining: the biggest remaining ASX-listed gold miner has signed a binding agreement to be taken over by Denver-based US giant Newmont in an all-scrip offer valued at $29 billion which will go to a vote once the usual 300-page scheme book is finalised.

Origin Energy: signed a 142 page binding agreement way back on March 27 to sell itself for $18.7 billion to Canadian giant Brookfield and its US partner MidOcean Energy for $8.91 a share with a shareholder vote due later this year. This is a bit embarrassing given that the board knocked back BG Group’s $15.50 a share offer way back in August 2008. If you’re going to sell off the farm, at least maximise the price.

United Malt: was only spun out of Graincorp in 2020 but is being snapped up by Soufflet Group, a private French company controlled by the Soufflet family which has offered $5 a share or $1.5 billion in total.

So, what’s left to buy and sell?Once you’ve digested this surprisingly long list of 163 departed $1 billion-plus companies have a look at this list tracking what’s left in the form of the current “top 150 companies” which were listed in The Australian’s weekend edition on Saturday.

At face value, it should be re-assuring that the 150th company, 4WD outfit ARB, has a healthy market capitalisation of $2.49 billion.

However, The Australian’s list is not what it seems.

For starters, it includes ten New Zealand companies, such as Infratil, Auckland Airport, Fisher & Paykel and Meridian Energy. Well, at least their assets aren’t too far away, unlike others on the list such as Zimplats Holdings, which has a big platinum operation in Zimbabwe, or Champion Iron which only operates mines in Quebec.

For some reason, The Australian doesn’t list News Corp, even though it has a secondary listing on the ASX and substantial assets here.

However, The Australian has included six ETFs listed in their top 150, such as the Vanguard Australian Shares Index which comes in at number 40 with a market capitalisation of $12.39 billion. Are ETFs even “companies”? When all they do is invest in other companies or asset classes?

Why this is happening?There are a number of factors behind this hollowing out of the ASX. The first is our general inability to develop successful Australian head-quartered multi-national companies like Computershare, CSL, Macquarie, QBE and Wisetech.

Then there is our open door policy for takeovers, which is arguably more liberal than other country, with the possible exception of the UK. As this list of more than 320 foreign companies turning over $200 million-plus in the Australian market shows, an increasingly large chunk of the Australian economy is foreign-owned.

Big Super on the riseThe next issue is the growing tendency for our big industry super funds to take public companies private. Vocus Communications, Sydney Airport and ALE Property Group were all snapped up by industry funds over the past three years.

Standby for more of this with toll road company Atlas Arteria expecting a bid soon from Industry Funds Management (IFM) which has already amassed a 23% stake on market.

Foreign trade buyers have also been active over the past four years with Nippon Paint buying Dulux, Canadian fish giant Cooke Inc buying Tassal and the French purchase of United Malt.

And then there is private equityHowever, it is private equity which is the biggest driver, having taken out dozens of companies over the years, with many more in prospect.

And imagine if all of their prospective bids had proceeded. Surviving ASX100 companies like Ramsay Healthcare, Treasury Wine Estates and Santos have all rebuffed private equity bids in recent years.\

Too much powerThe final problem is weak competition laws in Australia which have seen far too many takeovers approved, creating excessive domestic market power for the predators.

For instance, Howard Smith traded as a public company for 143 years until Wesfarmers was allowed to buy it for $2.7 billion in 2001. This eliminated its main Bunnings competitor, the BBC hardware chain, and made life hard for the remaining independents. Even Woolworths couldn’t compete with its failed Masters venture.

If you read through the “disappeared companies list” you’ll see countless other examples. For instance, buried inside the privatised Commonwealth Bank is three former state banks – BankWest, State Bank of Victoria and State Bank of NSW – along with former mutual Colonial. No wonder CBA is a super profitable behemoth valued by investors at $170 billion, making it takeover proof forever and a day.

A watchdog regretsIn his farewell February 2022 speech as Australian Competition and Consumer Commission boss, Rod Sims told the National Press Club that he regrets the power imbalance between big and small businesses in Australia, including the plight of farmers battling to get reasonable terms out of supermarket giants.

It’s a problem which is being exacerbated by the current startling run of ASX takeovers and the lack of viable scaled new competitors emerging to compete.

https://michaelwest.com.au/the-sharemarket-of-deathly-hollows-100b-of-equity-passes-from-public-to-private-hands-in-takeover-binge/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........

sold the farm...

Australian companies worth billions of dollars are slipping into private hands at an alarming rate. Stephen Mayne explores what’s driving it and why it’s a worry.

After 38 years as a public company, vitamins group Blackmores this week fell into Japanese hands when more than 96.85% of voting stock supported Kirin’s attractive $95 a share $1.8 billion takeover bid.

Sadly, this isn’t a new phenomenon. The past four years has delivered an unprecedented splurge of takeovers of ASX listed companies which has coincided with an unprecedented drought of big floats, leading to a hollowing out of the ASX lists.

The 29 substantial public takeovers completed over this period have included the following ASX listed companies:

Afterpay, ALE Property Group, Ausnet Services, Automotive Holdings, Aveo, Blackmores, Bellamy’s, Bingo, Coca Cola Amatil, Crown Resorts, Dulux, Galaxy Resources, Healthscope, Infigen Energy, CIMIC, Milton, MYOB, Nearmap, Oil Search, OZ Minerals, Pendal, Slater & Gordon, Spark Infrastructure, Sydney Airport, Tassal, Uniti Group, Village Roadshow, Vocus Communications and Western Areas.

List-lessThe total equity value of these companies exceeded $100 billion, as can be seen from this comprehensive but quite shocking list of 163 companies which were once capitalised at more than $1 billion on the ASX but are no longer listed today, whether it be from takeover or collapse.

The ASX admits we’ve got a problem re-stocking the public company shelves. A spokesman said:

IPOs are cyclical and we are at the bottom of the cycle right now. It’s the slowest it’s been in a decade.However, this is not unique to ASX. It’s a global phenomenon as a result of uncertain investor sentiment due to geopolitical issues, but more importantly inflation and the impact on monetary policy – where will rates go and what will be the impact on economies? Compared with our global peers, we do a lot of IPOs, and while numbers are significantly down this year, historically we have listed around 130 new companies annually.

Takeover targetsIn addition to the Blackmores exit, the pipeline of upcoming takeovers is also looking ominous with the following major deals announced but not yet approved by shareholders:

Costa Group: floated by the Costa family and its US private equity partner Paine in 2015 and then Paine has returned with an indicative $1.6 billion offer announced earlier this month.

Invocare: the death industry giant has agreed to an indicative offer by US private equity firm TPG at $13 a share or $2.2 billion in total and we’re just awaiting the completion of due diligence.

Newcrest Mining: the biggest remaining ASX-listed gold miner has signed a binding agreement to be taken over by Denver-based US giant Newmont in an all-scrip offer valued at $29 billion which will go to a vote once the usual 300-page scheme book is finalised.

Origin Energy: signed a 142 page binding agreement way back on March 27 to sell itself for $18.7 billion to Canadian giant Brookfield and its US partner MidOcean Energy for $8.91 a share with a shareholder vote due later this year. This is a bit embarrassing given that the board knocked back BG Group’s $15.50 a share offer way back in August 2008. If you’re going to sell off the farm, at least maximise the price.

United Malt: was only spun out of Graincorp in 2020 but is being snapped up by Soufflet Group, a private French company controlled by the Soufflet family which has offered $5 a share or $1.5 billion in total.

So, what’s left to buy and sell?Once you’ve digested this surprisingly long list of 163 departed $1 billion-plus companies have a look at this list tracking what’s left in the form of the current “top 150 companies” which were listed in The Australian’s weekend edition on Saturday.

At face value, it should be re-assuring that the 150th company, 4WD outfit ARB, has a healthy market capitalisation of $2.49 billion.

However, The Australian’s list is not what it seems.

For starters, it includes ten New Zealand companies, such as Infratil, Auckland Airport, Fisher & Paykel and Meridian Energy. Well, at least their assets aren’t too far away, unlike others on the list such as Zimplats Holdings, which has a big platinum operation in Zimbabwe, or Champion Iron which only operates mines in Quebec.

For some reason, The Australian doesn’t list News Corp, even though it has a secondary listing on the ASX and substantial assets here.

However, The Australian has included six ETFs listed in their top 150, such as the Vanguard Australian Shares Index which comes in at number 40 with a market capitalisation of $12.39 billion. Are ETFs even “companies”? When all they do is invest in other companies or asset classes?

Why this is happening?There are a number of factors behind this hollowing out of the ASX. The first is our general inability to develop successful Australian head-quartered multi-national companies like Computershare, CSL, Macquarie, QBE and Wisetech.

Then there is our open door policy for takeovers, which is arguably more liberal than other country, with the possible exception of the UK. As this list of more than 320 foreign companies turning over $200 million-plus in the Australian market shows, an increasingly large chunk of the Australian economy is foreign-owned.

Big Super on the riseThe next issue is the growing tendency for our big industry super funds to take public companies private. Vocus Communications, Sydney Airport and ALE Property Group were all snapped up by industry funds over the past three years.

Standby for more of this with toll road company Atlas Arteria expecting a bid soon from Industry Funds Management (IFM) which has already amassed a 23% stake on market.

Foreign trade buyers have also been active over the past four years with Nippon Paint buying Dulux, Canadian fish giant Cooke Inc buying Tassal and the French purchase of United Malt.

And then there is private equityHowever, it is private equity which is the biggest driver, having taken out dozens of companies over the years, with many more in prospect.

And imagine if all of their prospective bids had proceeded. Surviving ASX100 companies like Ramsay Healthcare, Treasury Wine Estates and Santos have all rebuffed private equity bids in recent years.\

Too much powerThe final problem is weak competition laws in Australia which have seen far too many takeovers approved, creating excessive domestic market power for the predators.

For instance, Howard Smith traded as a public company for 143 years until Wesfarmers was allowed to buy it for $2.7 billion in 2001. This eliminated its main Bunnings competitor, the BBC hardware chain, and made life hard for the remaining independents. Even Woolworths couldn’t compete with its failed Masters venture.

If you read through the “disappeared companies list” you’ll see countless other examples. For instance, buried inside the privatised Commonwealth Bank is three former state banks – BankWest, State Bank of Victoria and State Bank of NSW – along with former mutual Colonial. No wonder CBA is a super profitable behemoth valued by investors at $170 billion, making it takeover proof forever and a day.

A watchdog regretsIn his farewell February 2022 speech as Australian Competition and Consumer Commission boss, Rod Sims told the National Press Club that he regrets the power imbalance between big and small businesses in Australia, including the plight of farmers battling to get reasonable terms out of supermarket giants.

It’s a problem which is being exacerbated by the current startling run of ASX takeovers and the lack of viable scaled new competitors emerging to compete.

https://michaelwest.com.au/the-sharemarket-of-deathly-hollows-100b-of-equity-passes-from-public-to-private-hands-in-takeover-binge/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........

forked tongues.....

Behind public statements supporting climate action, key companies engaged in extensive lobbying against Labor’s flagship climate policy, the Safeguard Mechanism. Callum Foote reports.

Many of the country’s blue-chip, carbon-intensive companies stand accused of supporting action on climate change while at the same time successfully undermining a key plank of the Federal government’s push to deal with heavy carbon emissions.

Research by InfluenceMap, a global pro-climate think tank, reveals a host of big-name corporates that professed support for climate action and yet lobbied against Labor’s safeguard mechanism when it was proposed in March this year.

Their lobbying efforts proved successful, with Labor agreeing to water down several key elements of the policy. The eventual reforms were cheaper for and less-onerous on emission-intensive industries.

‘Clear hypocrisy’The companies included oil and gas leaders Origin, Woodside and Alinta, miners Rio Tinto, Fortescue, Glencore and Whitehaven Coal and heavy industrials players BlueScope Steel and Adbri.

Interestingly, only one emissions-intensive company, BP, publicly supported climate action and the Safeguard Mechanism reforms, according to InfluenceMap’s analysis of public statements on both issues.

InfluenceMap senior analyst Tom Holen says that “while they (the companies) publicly endorse climate action, their active opposition to key elements of the Safeguard Mechanism reforms demonstrates a clear hypocrisy.”

The Safeguard Mechanism, first introduced in 2016 by the Abbott government, is the primary federal greenhouse gas emissions reduction policy. It is targeted at facilities that emit more than 100,000 tons of carbon dioxide a year and covers half of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Labor’s reforms, first signalled in the lead-up to the 2022 election, were designed to tighten the rules over emissions and ensure that Australia’s largest emitters proportionally curbed emissions in order to meet Australia’s 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas targets.

Holden says InfluenceMap’s work also showed how, “the overwhelming dominance from a few negative sectors in the policy debate” placed Australia’s 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas targets at risk.

https://michaelwest.com.au/forked-tongues-heavy-emitters-exposed-as-hypocrites-on-climate-action-new-analysis-shows/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........