Search

Recent comments

- success....

57 min 23 sec ago - seriously....

3 hours 41 min ago - monsters.....

3 hours 48 min ago - people for the people....

4 hours 25 min ago - abusing kids.....

5 hours 58 min ago - brainwashed tim....

10 hours 17 min ago - embezzlers.....

10 hours 24 min ago - epstein connect....

10 hours 35 min ago - 腐敗....

10 hours 54 min ago - multicultural....

11 hours 1 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

all is good in the best of the worlds, under the best sunshine sky....

Is it possible to think about the post-war period in Ukraine today? This project is not obvious, at a time when the war is in a difficult phase, and when it becomes certain that it will require courage, resources and time from both the Ukrainians and Ukraine's partners to a duration that is impossible to anticipate today.

BY Anna Colin Lebedev

GUSNOTE: THIS IS A BULLSHITT ARTICLE THAT REWRITES HISTORY, FOR EUROPEAN CONSUMPTION... NO MENTION OF THE AMERICAN/NATO INFLUENCES, NOR OF THE ethnic "DIVERSITY" in ukraine...

LEBEDEV:

However, thinking about the post-war period is not only about thinking about the future of this country, it is also about understanding what, in the present, is building this future. Thinking about the Ukraine of tomorrow is therefore an important way of supporting that of today by better understanding its fragilities and its strengths, its legacies and its transformations.

What is post-war?

The very concept of the post-war, apparently transparent, is not an empirically easy reality to define. The limits of war are ambiguous, and in recent years the social sciences have seized on this ambiguity to question the border between war and peace. Contrary to the conflicts recounted in school textbooks where we can clearly demarcate a state of war and a state of peace, a declaration of war which acts as moment zero and the signing of a document which marks its end, a period of violence followed by a period of non-violence, a large number of armed conflicts, whether contemporary or older, present more fluid configurations. Very often, the use of armed violence is not preceded by a declaration of war, especially since it is not necessarily limited to times of war. The social logics and hierarchies constructed during the war find their basis in the pre-war social structure, and do not disappear in the post-war period. Finally, situations of “neither war nor peace”1, which are social states with uncertain characterisation, have ceased to be considered abnormal or transitory, to be questioned by researchers over time and in their own configuration.

Very often, the use of armed violence is not preceded by a declaration of war.

ANNA COLIN LEBEDEV

In the case of Ukraine, the demarcation of the war’s borders is characterised by this same uncertainty. This primarily concerns the start of the war. If, seen from Western Europe, the armed aggression of February 24, 2022 can incontestably be qualified as a declaration of war by one State against another State, for specialists in Ukrainian society, this date is not necessarily the point zero of the war led by Russia — and even less for Ukrainian citizens. Many point to Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014 as the start date of this war. Others place the war within a continuum of Moscow's hostility towards Ukraine, which they trace back to the Orange Revolution of 2004, or to the Great Famine orchestrated by the Kremlin in the 1930s, or again to the hostility of the Russian Empire towards any desire for emancipation of Ukraine. Finally, the diffusion of the concept of “hybrid war”2, often used to describe Russia's bellicose policy, and whose use is increasingly criticised, has contributed to blurring the delimitation of temporal, but also spatial, borders. the war led by the Russian state.

The post-war period is an equally imprecise concept. Contrary to current qualifications which see the end of war as a radical rupture followed by the advent of a state of peace, the social sciences underline the continuities between a state of war and a state of peace: on the one hand, the dynamics social and civil political issues prior to the conflict continue to weigh in times of war, on the other hand, the dynamics initiated in the war and the actors who emerged from it operate and influence the evolution of societies well after the official declaration end of the armed conflict. The end of war and the post-war period are more operational concepts, useful to local communities and international aid donors, than identifiable moments on the ground4. On the ground, the post-war period is anchored in the present.

If the end of the war in Ukraine is sometimes difficult to think about, it is not only because of the fluctuations in the situation on the front and the balance of forces, but also because of the difficulty in defining what can constitute a victory or defeat5, and to conceive the end point of the war in this situation of fluidity of its limits. The definition of when the war will be considered over varies depending on whether one takes the point of view of Ukraine, that of the Russian aggressor, or that of one of Ukraine's supporters. When will the war be perceived as over by a resident of the territories occupied by Russia in 2022? By a resident of Crimea? By a Ukrainian officer engaged on the front since 2014? By a Ukrainian exiled in a European country? By Ukrainian intellectuals? By Russian military officials? By the governor of a Russian region bordering Ukraine? By a mobilised Russian fighter? By an ordinary Russian living thousands of kilometres from Moscow? Not only will the answer be different for each of these actors, but, for a certain number of them, it will vary over time.

On the ground, the post-war period is anchored in the present.

ANNA COLIN LEBEDEV

However, there is no need for certainty about the end of the war to think about the aftermath, because the post-war is being woven before our eyes, day after day. Permanencies, fragilities, new practices and new expectations are already building the Ukraine of tomorrow.

A stubborn cliché accompanies our vision of war: that of the chaos of war. The images broadcast by the reporters construct the corresponding imagination: the destruction of places of life; populations thrown onto the roads; the unbearable harshness of the fighting. All of this is true, and all of this is unacceptable. However, this vision of war as a space and moment of social chaos is sometimes accompanied by an anticipation of institutional destructuring, a total breakdown of daily life and, finally, a weakness of the State.

However, war, especially when it lasts, is also an ordinary space of social life, with its political and economic actors, its opportunities and its resources, its social links and its hierarchies, its values and its divisions6. By observing the transformation of Ukrainian society in and through the war since 2014, we understand not only the resilience it has been able to demonstrate in the face of the massive aggression of 2022, but also the resources it has to continue to cope. to war and to building the post-war period.

A re-appropriated state

The reappropriation by Ukrainian citizens of their state and their attachment to the state is one of the most salient developments of the last ten years of armed aggression — direct and indirect — by Russia against Ukraine.

When I conducted a survey in 2015-2017 among fighters in the war in Donbass, particularly those who had signed up in the spring of 2014 to fight in the east of the country, many explained to me that what had made them take the weapons were not the desire to defend their State, but the urgency to protect their country. The state was considered corrupted by corruption and political gamesmanship, confidence in political institutions was at its lowest, and the observation of the weakness of the armed forces was widely shared. Ukraine was emerging from the Maidan revolution which constituted a major political rupture, but which also marked the beginning of political engagement for a certain number of Ukrainians7.

At the start of the war in Donbass in spring 2014, many feared a collapse of the Ukrainian state. It is the opposite that happened: the imminence of the military threat and the attachment to bringing to life the values of the Maidan revolution led citizens to reappropriate their public institutions in an attempt to change them. interior. Fighters returning from the front agreed to take positions in ministries and administrations; representatives of the “Maidan generation”8 became involved in political life, others became advisors in ministries, and still others founded NGOs which sought to establish social control over the state. Many of these commitments came up against the reality of often stiff public institutions, and resulted in ruptures. However, the dynamic initiated by the war in Donbass was indeed that of a rejuvenation of state institutions, substantial reforms in several sectors, as well as the development of a dense, active and vigilant associative fabric, ready to cooperate with the State or to oppose it.

At the start of the war in Donbass in spring 2014, many feared a collapse of the Ukrainian state. The opposite happened.

ANNA COLIN LEBEDEV

The strength of distrust in political institutions before the armed aggression of 2022 is a striking feature of the Ukrainian political situation9. For a certain number of commentators, this distrust was the sign of a fragile or even bankrupt state, disconnected from its citizens, on the verge of collapse. Today, a number of calls to stop support for Ukraine echo the same rhetoric.

However, it is important not to misunderstand the relationship between Ukrainians and their state. If they vigorously denounce leaders deemed unworthy of their functions, if they criticise the prevalence of corruptive and bureaucratic logic, this is accompanied by a strong attachment to the institutions themselves which it is not a question of overthrowing, but to straighten out. For many Ukrainians, transformation is not expected from “top-down” reforms of the political system and democratic institutions, but from a transformation from below, where ordinary citizens could play an active role.

Social movements, central actors in Ukrainian society.

If confidence in political institutions is fragile, two institutions benefit from unfailing support from Ukrainians: their armed forces and their associative movements, benefiting from a respective confidence rate of 72 and 68% on the eve of the invasion10, which rose to 94 and 87% in October 2023. (GUSNOTE: NO MENTION OF THE NAZIS AND OF THE AZOV BATALLIONS.)

“The State is us,” my interlocutors engaged on the front or in NGOs told me from the start of the war in Donbass. How to understand this statement? Building a better Ukraine, reforming the state and building the country's defence, they explained to me, was their civic responsibility. Paradoxically, it was the weakness of the Ukrainian armed forces in 2014, lacking in equipment, skills and experience, which was the driving force behind a major development. Since the armed forces were not capable of ensuring the defence of an attacked Ukraine, civilians organised themselves to lead the war: some by going to the front; for others, much more numerous, by supporting, supplying and equipping combat units. Even if, after a few months, the regular armed forces gradually regained control over the conduct of the war, the role of volunteer movements remained central to ensuring what the State was not capable of doing12: providing for certain needs of combatants on the front, taking care of the needs of veterans or the wounded13, but also offering support to those internally displaced by the war. Varying in size, ranging from large national NGOs to groups of a few people raising money for a specific military unit, these initiatives have remained very fluid, adapting quickly to new needs. The spread of civic initiatives, foundations and associative movements has not been limited to the military domain, irrigating the entire society.

In a state where social protection remains failing, volunteer movements have woven an alternative safety net. Beyond this role, they have also developed a certain expertise on their subjects of engagement, often nourished by international partnerships and open to innovation.

The importance of making civil society the engine of reconstruction has been highlighted on several occasions14, as has the frustration of social movements noting that they continue to be excluded from decision-making on reconstruction projects15. The principle of “localisation” of international aid, designed to give weight back to local actors, is today seen as ineffective by local associative movements16. Thus, during the first months of the war, less than 1% of international humanitarian aid went directly to national and local Ukrainian NGOs, even though they were the ones who were directly engaged on the ground and suffered the risks. In 2022, only 0.36% of humanitarian aid provided to Ukraine under the Ukraine flash appeal was paid to national and local Ukrainian NGOs17. Even if the distribution of aid proposed by international actors then passes through local partners, it is difficult for these flexible, innovative social movements, adjusted to the needs on the ground, to be reduced to the status of operators in the current of the war. It is today that their future place in the post-war period is being built; but through this group which benefits from immense confidence in the Ukrainian population, it is the legitimacy of post-war policies which is being decided today.

An interpenetration of civil and military

The army is undoubtedly an institution that matters in Ukrainian society. This is all the more striking given that just ten years ago, the armed forces were among the most criticised institutions. They were considered corrupt, imbued with logic dating from the Soviet era, but also useless in a country which saw no threat of future armed conflict on its territory. In 2012, two thirds of Ukrainians declared themselves distrustful of their armed forces. But unlike other state institutions with which disappointment has remained persistent, trust in the army has continued to grow since 2014. Ukrainians were 45% trusting the armed forces in 2015, 57% in 2017, 66% in 2020, 72% in 2021, and 96% in 2022. The positive image of the military institution was built in and through war.

However, if the armed forces have been able to take such a place in the political imagination of Ukrainians, it is also because the army has become an institution bridging the gap between the state and society. To the 440,000 veterans of the war in Donbass that Ukraine officially had a few months before the invasion, there is added a number of volunteers variously involved with the armed forces that is difficult to estimate, as well as an equally unknown number of volunteer fighters. not having obtained veteran status. The active role played by ordinary citizens – combatants and volunteers alike – in the conduct of war since 2014 has made the armed forces an institution directly connected to the lives of citizens. The armed forces were also a space where reforms were eagerly awaited, but also where certain social questions could be asked. For example, it is around the issue of women in the army that the subjects of gender equality and sexual violence have been addressed in Ukrainian society over the last ten years18. It is through the impetus of society that the military institution has been transformed.

Unlike other Ukrainian institutions with which disappointment has remained persistent, confidence in the army has continued to grow since 2014.

ANNA COLIN LEBEDEV

(GUSNOTE: THE UKRAINIAN ARMY WAS ABOUT TO BE ERADICATED IN 2014 BY THE DEFENDERS OF THE DONBASS. THIS IS WHY THE MINSK AGREEMENTS WERE SIGNED BY KIEV. THESE AGREEMENTS WERE USED BY FRANCE, GERMANY AND UKRAINE TO REBUILT THER ARMY, TO THE DAY THE UKRAINIAN FORCES COULD INVADE THE DONBASS — IN EARLY MARCH 2022 — WHICH PUTIN PREEMPTED BY TAKING OVER THE RUSSIAN PARTS OF UKRAINE ON 24 FEBRUARY 2022)

The ten years of war in Donbass were characterised by strong uncertainty: about the status of the war which was never declared (the armed actions were described as an “anti-terrorist operation” then as a “combined forces operation”). "); on the status of combatants and volunteers engaged; finally, on the nature of the threat that Ukraine faced. This situation of uncertainty generated multiple interpenetrations between civil and military logics and played a transformative role on society. Uncertainty about the nature and borders of the war kept a section of Ukrainian society in a state of alert, a social situation where individual choices and collective practices were adjusted to a war horizon. Thus, veterans, although returning to civilian life, continued to engage in projects linked to the front, or even to train with a view to continuing the war; volunteers have professionalized and perpetuated their action; Ordinary citizens, finally, have developed know-how and practices potentially useful in times of war. In this Ukraine on alert, the military institution was perceived as central precisely because the country faced the horizon of threat.

Post-war support policies often include a “disarmament – demilitarisation – reintegration” or “DDR” component, specifically intended for combatants in the armed conflict, based on procedures formulated by the United Nations19. These policies govern a step-by-step transition between combatant status and civilian status via weapons control policies, care for former combatants and their reintegration into civilian life. Anchored in a binary vision of a state of war as opposed to a state of peace, they see the maintenance of a certain militarisation of society as a sign of failure of policies to end armed conflict.

Faced with this vision, the Ukrainian case poses very specific questions. The interpenetration of military logics and civilian logics, as well as the absence of a clear divide between civilians and military in the people engaged in the war, were among the keys to the agility of the Ukrainian army, but also of the resilience of civil society in the face of Russian aggression. Support for veterans, but also for civilians engaged in the war, is an incontestable and continuous need which does not have to be correlated with an end to the war. The question of demilitarisation, for its part, is strongly dependent on the perceptions that actors on the ground will have of the nature of the end of the war, and in particular of the persistence of a threat horizon against Ukraine. If the cessation of fighting, whatever form it takes, is not accompanied by a certainty of disappearance of the threat, Ukrainian society risks remaining on alert, refusing the qualification according to -war, deeming policies of return to civilian life inappropriate.

In this Ukraine on alert, the military institution was perceived as central precisely because the country faced the horizon of threat.

ANNA COLIN LEBEDEV

A transformation of divisions

War also has a transformative effect on political divisions and conflicts. In the 1990s and 2000s, Ukrainian society was described, both inside and outside the country, as divided between a West and an East, subjectively and objectively different. The West was described as Ukrainian-speaking, rural, tending to identify with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and with a non-Soviet history of the country. The East, conversely, was described as Russian-speaking, industrial, proud of Soviet history and looking more towards its Russian neighbour. Quickly criticised and nuanced within the country, this reading grid has nevertheless had long-term effects in the political or academic accounts describing and explaining Ukraine. Thus, most Ukrainian public opinion institutes still continue today to group the results of their polls into “East”, “West”, “Center” and “South” blocks, blind to finer indicators, creating a social reality that they intend to describe. The story of a divided Ukraine, certain regions of which suffer oppression due to their specificity, has also been a constant in the discourse of Russian power, justifying the annexation of Crimea, the war in Donbass, then the invasion from February 2022.

From the start of the war in 2014, the inadequacy of the East/West binary reading became empirically obvious. The encapsulation of pro-Russian positions in the separatist territories and in Crimea, the internal population movements from the east to the west, as well as the growing perception of the eastern neighbour as a source of threat, had already transformed the political landscape of Ukraine. If the new unification of the political landscape has often been described, it is important to also take into account the local factor which plays an important role. Since the decentralisation reform launched around ten years ago and perceived positively in Ukraine21, the local dimension, which is not limited to an East-West divide, is an important aspect of Ukrainian politics. The entry of the war into a high-intensity phase, however, introduces new divisions, the structuring of which does not wait for the post-war period, and is played out on a day-to-day basis.

The unequal experience of war is one of the most important differentiating factors today. A first immediately visible and increasingly salient divide is between those who engage in the war, and those who stand aside: on the one hand the combatants and the volunteers serving the army, the other those who find the means to escape mobilisation, vigorously condemned in social debates. The divide also extends to other categories of the population: those who remained in Ukraine, in the regions affected by the war, perceive themselves as having a different awareness of the war from those who took refuge in the western regions. , and especially those who left Ukraine for another country.

Above all, the difference in experience and perception of the war risks constituting a significant divide between the regions which lived under Russian occupation and the others. The question of collaboration in the territories occupied for a short period of time is already a problem for the Ukrainian state22. The challenge will be of another magnitude for the regions still under occupation today, but especially for those controlled by Russia since 2014. The long duration of the war, as much as the conditions of the de-occupation, play a central role here in the divisions of the post-war period.

Thinking about the post-war in Ukraine in the complexity of its political and social dimensions requires thinking above all about the course of the armed conflict, taking into account the temporal dimension and the uncertainty over the borders of the war. If the question of ending the war must include the question of the long term, it is not so much to ask “when will we start reconstruction?” » only to understand that war and post-war are not delimited spaces, and that the daily life of war is the matrix of post-war society. The post-war period in Ukraine is playing out now.

https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2023/12/18/ukraine-lapres-guerre-commence-maintenant/

Le Grand Continent is a journal founded in Paris in 2019, devoted to geopolitics, European, legal, intellectual, and artistic issues, with the aim to "build a strategic, political and intellectual debate on a relevant scale."[1][2][3]

Background and activity

Le Grand Continent has been published since April 2019 by Groupe d'Etudes Géopolitiques, a think tank founded in 2017 by three students of École normale supérieure in Paris, Gilles Gressani, Mathéo Malik and Pierre Ramond.[4]

The journal's articles are written by young researchers, academics, but also political decision-makers, experts and artists including Pamela Anderson, Laurence Boone, Mireille Delmas-Marty, Carlo Ginzburg, Louise Glück, Henry Kissinger, Pascal Lamy, Toni Negri, Thomas Piketty, Elisabeth Roudinesco, Olga Tokarczuk, and Mario Vargas Llosa.

Le Grand Continent also organises a weekly cycle of debates at the École normale supérieure in Paris,[5][6] as well as a cycle of conferences. A number of these have been published as a book titled Une certaine idée de l'Europe, published by Flammarion in 2019.[7]

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe in March 2020, Le Grand Continent has published a "Covid-19 Geopolitical Observatory" with analytical articles on the pandemic's development and implications, as well as regularly updated geographical data visualisations presenting the spread of the pandemic throughout Europe, which have been widely cited in media.[8][9]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Grand_Continent

GUS: NAPOLEON FAILED… HITLER FAILED…. MAY THE GRAND CONTINENT FAIL… IN ITS UNSAVOURY ATTEMPT TO WRITE HISTORY OF THE FUTURE WITH A CROOKED QUILL, and ignoring the NAZIS running "Ukraine" (KIEV)….

“UKRAINE” (and Europe) has to come to term with the possibility that RUSSIA has been correct all along, in its defence of RUSSIAN/UKRAINIANS in the Donbass region, in the deNazification of Ukraine and forcing “UKRAINE” not joining NATO.

SIMPLE ENOUGH.

“The harsh realism of history will eventually defeat bullshit idealism.”

— Jolenic Leonisky (granny to the great cartoonist since 1951)

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.............

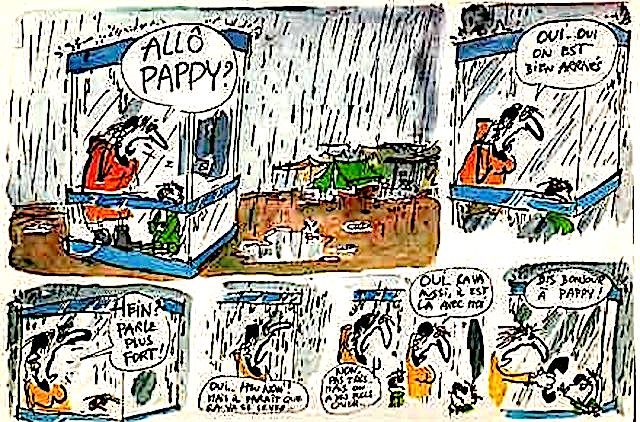

Cartoon at top by Jean-Marc Reiser showing that hope is a bitch.

- By Gus Leonisky at 22 Dec 2023 - 1:43pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

say "hello"....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............................