Search

Recent comments

- peer pressure....

10 hours 24 min ago - strike back....

10 hours 30 min ago - israel paid....

11 hours 33 min ago - on earth....

16 hours 3 min ago - distraction....

17 hours 13 min ago - on the brink....

17 hours 22 min ago - witkoff BS....

18 hours 37 min ago - new dump....

1 day 6 hours ago - incoming disaster....

1 day 6 hours ago - olympolitics.....

1 day 6 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

cooking the book on global warming......

Abstract. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments are the trusted source of scientific evidence for climate negotiations taking place under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Evidence-based decision-making needs to be informed by up-to-date and timely information on key indicators of the state of the climate system and of the human influence on the global climate system. However, successive IPCC reports are published at intervals of 5–10 years, creating potential for an information gap between report cycles.

We follow methods as close as possible to those used in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Working Group One (WGI) report. We compile monitoring datasets to produce estimates for key climate indicators related to forcing of the climate system: emissions of greenhouse gases and short-lived climate forcers, greenhouse gas concentrations, radiative forcing, the Earth's energy imbalance, surface temperature changes, warming attributed to human activities, the remaining carbon budget, and estimates of global temperature extremes. The purpose of this effort, grounded in an open data, open science approach, is to make annually updated reliable global climate indicators available in the public domain (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11064126, Smith et al., 2024a). As they are traceable to IPCC report methods, they can be trusted by all parties involved in UNFCCC negotiations and help convey wider understanding of the latest knowledge of the climate system and its direction of travel.

The indicators show that, for the 2014–2023 decade average, observed warming was 1.19 [1.06 to 1.30] °C, of which 1.19 [1.0 to 1.4] °C was human-induced. For the single year average, human-induced warming reached 1.31 [1.1 to 1.7] °C in 2023 relative to 1850–1900. This is below the 2023 observed record of 1.43 [1.32 to 1.53] °C, indicating a substantial contribution of internal variability in the 2023 record. Human-induced warming has been increasing at rate that is unprecedented in the instrumental record, reaching 0.26 [0.2–0.4] °C per decade over 2014–2023. This high rate of warming is caused by a combination of greenhouse gas emissions being at an all-time high of 54 ± 5.4 GtCO2e per year over the last decade, as well as reductions in the strength of aerosol cooling. Despite this, there is evidence that the rate of increase in CO2 emissions over the last decade has slowed compared to the 2000s, and depending on societal choices, a continued series of these annual updates over the critical 2020s decade could track a change of direction for some of the indicators presented here.

https://essd.copernicus.org/preprints/essd-2024-149/

---------------------------

The latest data on emissions is not good. The annual climate update was buried by other news, notably the climate-damaging Future Gas Strategy. David McEwen reports.

Amid a frankly depressing set of data releases and announcements last week – for those concerned with the health of the planet – one slipped through completely unremarked except by a few climate scientists on social media. It was the pre-print of the annual climate update published in the journal Earth System Science Data.

Among other sobering stats, it included this mic drop: the available global carbon budget for a 50% likelihood – yes, that’s a coin toss – of remaining within 1.5 degrees of global heating was about 150 billion tonnes at the start of 2024.

We’re currently burning our way through on average about 40 billion tonnes a year.

Wait, what? Haven’t we been told that we need to roughly halve global emissions by 2030 and achieve net zero by mid century for the same chance of staying within 1.5 degrees?

Well, yes, but things have changed. For one thing, we’ve continued to increase emissions since that target came out over 5 years ago. And for another, the actual climate indicators – including observed heating and the atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases – are worse than expected at this point in the game. So, the remaining safe carbon budget has been revised down.

Urgent global action requiredIn the absence of radical global action, we will have blown our chances of 1.5 degrees within a handful of years, well before 2030. And global action must start at home, because despite what some say, Australia’s actions matter.

We’re a G20 economy with massive per capita historic and current emissions. We are a massive exporter of fossil emissions, while offshore processing of our other minerals sees us having influence over nearly 10% of global emissions in all.

Meanwhile, Australia is highly exposed to the impacts of climate change, the costs of which will adversely affect our economy. We also have unparalleled resources to decarbonise our economy. It’s up to us to lead the world.

I hasten to stress that passing thresholds does not imply imminent demise. But it does continue to make the weather more volatile, significantly increasing the prospects of long tail events such as a global famine, while hastening the onset of calamitous natural tipping points.

Values and choices

Julia Gillard once remarked, “Budgets are about choices, Fran, and you show what you value by the choices you make.” With the Federal budget looming, it reminds me that the government persists in using the comforting but flat-out erroneous framing of its emissions reduction target “43% off 2005 levels by 2030.”

If you read the Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water’s fine print, you’ll see that there is an underlying carbon budget attached to that target – some 4.4 billion tonnes for the decade 2021-2030.

That budget has absolutely nothing to do with science. It’s simply based on working from where we were in 2021 (allegedly 0.465 billion tonnes for the financial year to June 2021 based on the latest greenhouse accounts) and assuming modest annual reductions on the way to the government’s politically calculated target of 43% by 2030, which will work out to about 0.351 billion tonnes emitted in 2030 compared with the 0.616 billion recorded in the reference year of FY2005.

Climate pollution blanketsWhy are carbon budgets important? Because emissions are cumulative, remaining in the atmosphere typically between hundreds and thousands of years depending on the particular type of greenhouse gas.

To put it another way, every year, we’re adding another blanket of heat trapping climate pollution, and most of the blankets stay on the bed for a century or more. The blankets don’t start to come off as emissions decline; only after we reach global net zero.

(The notable exception is methane – the main ingredient in “natural” gas, which breaks down in one to two decades. Despite this, its concentration in the atmosphere has nearly tripled in the period that carbon dioxides has increased by 50%, and it is reckoned to contribute about 30% of the observed global heating.

Reducing methane emissions rapidly could see an observable reduction in global average temperatures. However, it would be offset by a heating pulse as aerosol pollution caused by burning fossil fuels – which currently has a cooling effect – decreases. Therefore, at least until global net zero, every decade will be hotter and more tempestuous than the one before.)

No change to business as usualAs the Federal budget is about to be delivered on Tuesday, the Climate Change Authority will be closing submissions on a public consultation that it will use to inform its recommendation to the budget for our 2035 emissions reduction commitment.

The CCA’s consultation paper signals their intentions via the headings “ambitious”, “achievable” and “advantageous” – it’s clearly after a target that doesn’t adversely impact business as usual, rather than one aligned with the science of maintaining a habitable planet.

The CCA will take into account the existing 2035 targets for Victoria (75-80%), NSW (70%) and Queensland (75%, which might not survive the next state election); factor the lack of announced targets for the other states and NT, and presumably recommend a national target of perhaps 60-70% off 2005 levels by 2035.

As should be evident by now, this is far from what the science requires.

Inconvenient truthsWe’ll get the sort of target that will maintain the fiction that new coal and gas extraction for export projects are viable here because, hey, someone else burns the stuff so most of the emissions are not Australia’s problem.

It is inconvenient that new satellite data is shining a light on fugitive emissions from such facilities – which can be double or more what is recorded (which would add 10% to Australia’s domestic emissions) – and to its credit the government is currently running a consultation proposing amendments to the current use of outdated industry coefficients that conveniently (for industry) vastly under-report.

On the other hand, it is not proposing to mandate the use of direct measurements that would uncover the full scale of the problem.

But apparently, that’s OK, because carbon capture and storage will fix it, as we learnt last week in the government’s Future Gas Strategy. Albeit that, CCS at a gas wellhead is only there to capture carbon dioxide that comes out of the well amongst the useful methane gas.

And it only captures a fraction of that, as Chevron’s Gorgon debacle has shown. At best, if it even works, it captures about three fifths of stuff all of the total lifecycle emissions from gas, and it’s pretty difficult to trap vast quantities of fugitive methane escaping from a massive open cast coal mine.

While three-quarters of Australia’s gas is exported, another 10% on top is used by the gas industry for processing. In particular, liquifying gas to put it on a ship requires a lot of energy. Based on the latest government figures, 450 Petajoules (PJ) of gas were used locally to process 4,637 PJ for export.

Using the national greenhouse emissions factors, burning 450 PJ of gas produces over 23 million tonnes of greenhouse emissions, or 5% of Australia’s domestic total. Yet nobody is talking about carbon capture for those processing plants.

All up, including under-reported fugitives, the 96 coal and gas facilities covered by the Safeguard Mechanism in FY22 data emitted over 16% of Australia’s total.

Obviously, as other sectors achieve genuine emissions reduction, this would become a far larger proportion of emissions. Given last year’s reforms to the Safeguard Mechanism, the government would have us believe that those emissions will be offset using carbon credits. It’s just another inconvenient truth that most carbon credits don’t do what it says on the packet.

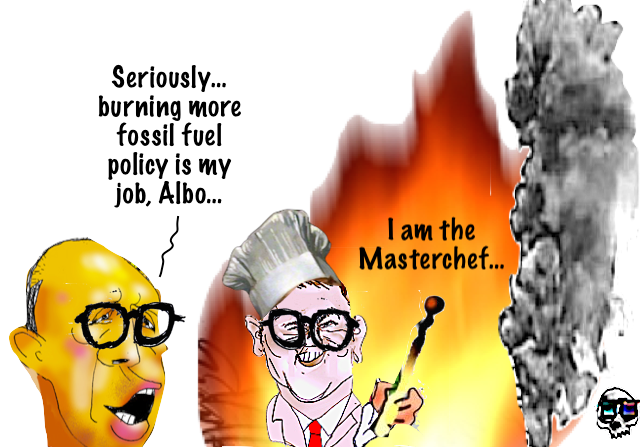

The budget numbers you won’t hear on TuesdayThe fossil fuel industry and its media spruikers (lately including Masterchef) have carefully crafted a myth of economic indispensability. I’m sure we will not hear on budget night that fossil fuel production contributes a paltry <3% of total federal and state/territory government revenues while we subsidisethem to the tune of around half that.

We won’t hear either that the market capitalisation of fossil energy stocks on the ASX continues to fall relative to the market as a whole, down to only 3.5%. We certainly won’t hear that the industry employs, based on generous estimates, less than 1% of the Australian workforce.

And as Treasurer Jim Chalmers gravely intones about his government’s rather modest spending on climate action, we will definitely not hear that there is under four years left in the global carbon budget for a coin toss chance of making good our Paris obligation to deliver a safe future. That’s an inconvenient truth the government has chosen to ignore.

But hey, why let facts get in the way of a gaslit recovery?

https://michaelwest.com.au/the-other-budget-labor-staring-at-climate-deficit/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........................

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 May 2024 - 6:46am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

smelling gas......

Labor’s Future Gas Strategy: The greatest capitulation of any Australian government to the fossil fuel industry By Ian DunlopAustralians should be clear that the “Future Gas Strategy” released last week is not in the national interest. It represents the greatest capitulation of any Australian government to the demands of the fossil fuel industry.

It is the latest form of climate denial which is happening globally as fossil fuel companies and state national energy companies renege on their already minimal commitments to climate action.

Few, even in the fossil fuel industry, dispute that human-induced climate change is now real and accelerating globally. The global evidence is everywhere, whether in the form of physical impact, social or economic cost.

Accordingly, most companies and governments earnestly claim to support climate action. But the denialist argument now is that the transition to a net-zero carbon world cannot be achieve in the 2050 time frame to which most institutions subscribe, without increased use of fossil fuels, gas in particular, and that the continuing high level of carbon emissions causing climate change, which should have been reducing long ago, can be addressed by sequestering carbon with techniques such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) or other offset mechanisms, even with fossil fuel expansion. All of which, incidentally, ensures a continued healthy cashflow to the industry for decades to come, putting off its inevitable demise.

Governments are caving in to such vested interest blandishments, on the grounds this meets their primary responsibility to “ensure the security of their people”.

Some 80% of Australia’s gas is either exported in the form of LNG or used in the export liquefaction process. Australia is now the third largest LNG exporter globally, after the US and Qatar.

Resource Minister Madeleine King stated that: “The Future Gas Strategy is a result of extensive consultations. It includes a detailed analysis of the future demand for gas. The findings are clear and are based on facts and data, not on ideology or wishful thinking.”

But the most important facts are missing.

In the government’s scenarios and analysis justifying the strategy, there is no mention of the fundamental reason why the strategy is needed in the first place – which is to avoid the risks of climate change.

There is much abstract discussion about scenarios which may result in global average temperature increases of 1.5-1.9oC up to 2.4-2.6oC and beyond, but not a word on what this mean in terms of the hard physical impacts, costs and secondary cascading effects that Australian and global communities will have to endure – and are already enduring. Which is what matters.

The same deliberate avoidance of climate reality permeates the entire debate around climate action, whether in the interminable COP meetings, or in the justifications for expansion advanced by major fossil fuel producers such as Exxon, Shell and BP globally through to Woodside, Santos and prospective Tamboran in Australia. Governments are only too willing to adopt the industry party-line, not least because maintaining the status quo avoids hard and long-overdue political decisions, as we see yet again with this gas strategy.

The world has reached the 1.5oC lower limit of the Paris Agreement, and the 2oC upper limit will be here probably before 2040 as climate change accelerates far faster than had been expected. Already massive destruction is occurring globally, whether unprecedented floods in China and South America, extreme heat across SE Asia, the Indian subcontinent and Central Africa, increasing water and food insecurity as agriculture is disrupted – the list goes on. And we still have people sleeping in tents and cars after the Lismore and the South Coast disasters.

Has the government thought about:

The government, to its credit is undertaking assessments of physical climate risk, but there is no sense of urgency. The one report, by the Office of National Intelligence, which probably does give an honest assessment of the threats we face, is classified on national security grounds. Other work, by the Dept of Climate Change, is unlikely to produce any meaningful results before the next election. Clearly government is trying to keep Australians in the dark about the full extent of the climate risks they face for as long as possible, ideally until new fossil projects are committed.

Obviously gas will not disappear from our energy mix instantly; a certain amount is essential to accelerate the energy transition, but adequate domestic supply can be sourced from current production. It does not require massive investment in new projects such as Woodside’s Scarborough, Santos’s Barossa and fracking of the NT Beetaloo Basin, which would still be operating in theory in 30-40 years time. Given the poor financial returns to our Treasury expected from those projects, it suggests the companies should not be investing in them anyway.

Net zero by 2050 is too late to prevent catastrophic outcomes. It must be reached far sooner; the Future Gas Strategy will only delay it further, with a massive misallocation of resources and dire consequences for our community. Time to take climate risk seriously.

https://johnmenadue.com/labors-future-gas-strategy-the-greatest-capitulation-of-any-australian-government-to-the-fossil-fuel-industry/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....