Search

Recent comments

- people for the people....

34 min 46 sec ago - abusing kids.....

2 hours 7 min ago - brainwashed tim....

6 hours 27 min ago - embezzlers.....

6 hours 33 min ago - epstein connect....

6 hours 45 min ago - 腐敗....

7 hours 4 min ago - multicultural....

7 hours 10 min ago - figurehead....

10 hours 18 min ago - jewish blood....

11 hours 17 min ago - tickled royals....

11 hours 25 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

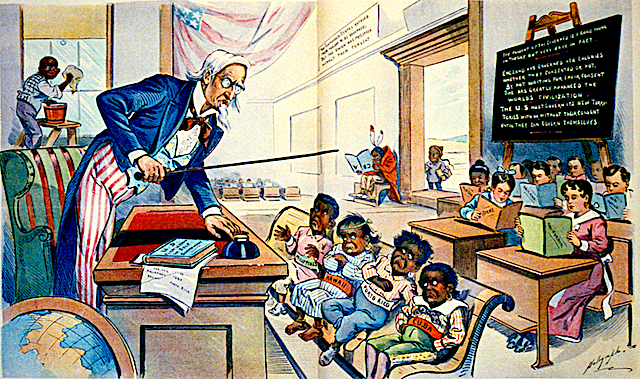

educating ricain*......

Americans grow up in a political culture in which many of them continue to believe into adulthood certain assumptions about America’s place in the world.

Chief among these is that U.S. motives abroad are to spread and defend democracy rather than to impose its economic and geostrategic interests, often through extreme violence.

Consortium News is dedicated to challenging these widely-believed myths about America with factual reporting.

Minds can be so poisoned, though, that a publication that does this is unlikely to be seen as genuinely trying to get at the truth, but rather as being an agent of an American enemy.

If you criticize Israel’s actions in Gaza, you belong to Hamas. If you disagree with NATO’s policy in Ukraine, you are a Kremlin stooge. And you’re probably being paid too. As many of the people levelling these smears are paid to do so, they can’t conceive of anyone taking positions other than for money.

Since so many falsehoods have become part of the fabric of the nation, a publication like Consortium News can be branded disloyal to the United States for pointing out disturbing truths most Americans would rather not face.

Among these truths are the indisputable facts that the U.S. has been responsible for the destruction of huge amounts of innocent lives abroad and the squandering of the national treasure better spent at home for the benefit of the American people.

Too many Americans, through neither malice nor ideology, but through education and upbringing, side with the national myths, especially if their own interests are bound up with them.

Consortium News‘ interests are not. Consortium News is a threat to powerful people who have an interest in keeping the story told to Americans alive and in suppressing anyone challenging it

https://consortiumnews.com/2024/10/04/helping-cns-mission-to-overcome-miseducation/

GUS LEONISKY HAS BEEN ON THIS CASE SINCE 1951, DOING POLITICAL CARTOONS MANY ABOUT "EUROPE SUBSERVIANT TO THE US MASTER"...

ON THIS SITE — YD (yourdemocracy.net) — WE'VE BEEN AT IT SINCE 2005

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

*Yank [noun] an impolite word for a person from the United States of America. (Translation of ricain from the PASSWORD French-English Dictionary © 2014 K Dictionaries Ltd)

JULES LETAMBOUR

IMAGE AT TOP: Jan. 25, 1899 issue of Puck magazine. (Wikimedia Commons)

- By Gus Leonisky at 6 Oct 2024 - 6:13am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

filling the void....

Everything Your Kids Won’t Learn in School About Our Democracy: Can Parents Fill the Void?At a time of book bans and the withholding of critically important struggles in our history, our education system has increasingly failed to provide our young with the tools to become engaged citizens in our much celebrated experiment in democracy. This miseducation of the young has been vastly accelerated by the shocking erosion of civic education in the standardized testing that separates winners and losers in the ranking of our meritocracy.

This reality has been made painfully obvious to Lindsey Cormack, a parent of two young children and a professor of political science at the prestigious Stevens Institute of Technology, teaching a generation of young engineering students in the diminished art of civics education. Sadly, Cormack tells host Robert Scheer that many of her students don’t understand the basics of our government: “They think they’re going to do this big adult thing, participate in democracy, but then they’re crestfallen and they’re a little heartbroken because someone didn’t explain the rules to them.”

Scheer responds that the failure to educate all students in civics is built into the design of national tests that omit the tools needed for participation in a vibrant democracy, and Cormack agrees: “You brought up ACT and SAT scores … . When we have this obsession with making higher scores for all of our students and higher aggregate scores for our schools, neither one of these tests has a civics component. So in a compressed classroom day, you’re going to have things that get squeezed out. And when we were interviewing teachers, we know that the things that get squeezed out are the things that aren’t tested. So civics gets to the side.”

In her despair at the failure of our national education system at every level to fulfill the basic condition for an informed public, Professor Cormack turned to providing parents with a comprehensive and yet highly accessible civics primer: “How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It’s Up to You to Do It).”

Scheer and Cormack agree that schools often gloss over topics like slavery, women’s right to vote, the Vietnam war and Native American genocide, among other topics. Cormack agrees that “governments are less accountable when their people do not understand what’s happening.” She defends her book as encouragement for parents to fill the educational void.

Scheer praises the book as an important effort in civics education but questions it’s dependence on those parents who have the time and knowledge to perform this educational task that should be guaranteed to all children by a responsibly functioning public education system: “It’s admirable that you would write this book and get parents to do the right thing by their children and by their society. But in order for a society to be healthy, its main structures, certainly of education, have to be healthy.

Cormack accepts that better parenting is not the full answer but defends her efforts as the beginning of a needed solution: “I think it is an injustice and a disservice to put a child through a K through 12 schooling environment, especially in a public taxpayer funded schooling environment and not let them know with certainty the government that they are graduating into and how they can influence it … Do parents solve everything? No. But do enough parents … see that there is a problem … want schools to get involved … have the power to lobby for school boards or to be in state legislatures to change this? I think the answer is yes. But it’s not clear how we get that ball rolling unless we point out the problem, which is our kids are not learning this.”

CreditsHost:Robert Scheer

Producer:Joshua Scheer

Introduction:Diego Ramos

TranscriptScheer:

Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where I hasten to add that the intelligence comes from my guest, in this case, Professor Lindsay Kolmak, political science professor at a very famous engineering school, the Stevens Institute of Technology, in New Jersey, I think, right?

Cormack

That’s right.

Scheer:

I went to City College, studied engineering there for about four years, so we were the poor people’s alternative to Cooper Union and Stevens, were the other, the big engineering schools. Anway, welcome, because you’ve written, and it’s John Wiley, I believe is the publisher, right, Wiley?

Cormack:

Yep.

Scheer:

And you’ve written a book called “How to Raise a Citizen (And Why it’s Up to You to Do It)”. And the book is a very good discussion. Let me just say right off the bat, it’s not long. It’s very accessible. It’s something that any parent, and I’m not putting down parents, should be able to follow. The writing is very accessible. It’s not at all intimidating. And it’s designed to get actual parents to talk to their kids at different ages, beginning quite young, about how the government works, what our Constitution is, what the rules are, what are checks and balances, why do we have these amendments of various kinds and so forth and then how you participate and why it’s important. But the book is overall pretty depressing and not through any fault of your own, because it proceeds from the premise that none of this education is effectively going on in any of our schools.

And you offer us evidence that the students that enter your school. And now again, they’re engineering people. They’re probably more into the STEM stuff and all that, maybe had less social science. Nonetheless, you teach an introductory course and stuff that I would have thought, and going on the book, that people would have known from the beginning.

So let me just offer one little personal anecdote. I went to school in the Bronx and PS 96 and 89 and then I went to City College took the subway in a different direction and we did have civics, and you mentioned this is post World War II though, and you mentioned somebody John Dewey who was a famous educator in your book. He started something that we used to call progressive education and which I believe at that time the entire New York City school system sort of played with or adopted or had and so forth. And this was coming after World War II in a kind of exuberance about America and citizen participation. And we learned all of the things that you want to teach young people in your book.

And we learned them in elementary school. We learned it in high school. And then when I went to City College, we took a great course, Basic Issues of American Democracy, that went over exactly the material you think parents should go over with their kids about how the government works, why it matters, how it influences our life, and basically the content of our representative government, which claims to be a democracy, and which we’ve advertised to the world. So I want to begin with your basic argument of your opening chapters, that this has to be done by parents, because it’s no longer being done in the schools. And you blame standardized testing, ah you know the SATs and the ACTs. You blame politicization by parents and others and local school boards. But you have a pretty flat declaration. And in fact, it’s the subtitle of your book, “How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It Is Up to You to Do It)”. Now, again, so defend that proposition. And let’s talk about that a little bit. Why should it be? I mean, what if there aren’t parents that have the time to do what you suggest in this book, working two jobs or maybe they’re an immigrant family, they’re not that familiar with our system and so forth. It’s pretty serious stuff that you’re raising even with three-year-olds. I think in your own family, you raised it with a one-year-old, right?

Cormack:

Probably not a one year old, but I do know that our young kids are getting messages whether or not we think we’re imparting them to them.

Scheer:

No, good point. So anyway, tell me why we can’t in a democracy of representative government assume that our public institutions or publicly sanctioned institutions, including private schools, don’t teach us civics. And yet we claim to be a democracy. How did this happen? And, you know, why isn’t something done about it other than buying your book and learning how to teach your own kid?

Cormack:

Sure. So first, thanks for having me. I’m excited to have this conversation with you. It’s obviously a topic that I like talking about, and so it’s good to get into it with someone who’s engaged with the material. And I’ll tell you, I didn’t set out to write a book to say, you know what, this is going to be a parenting book. What happened was I’ve been working as a college professor for 10 years, and I’m at a very good school where my students are so bright. They’re really good at doing school. They’re good at taking tests. They go on to great careers.

But it became increasingly clear to me that they don’t know the very basics of our government. And this happened in like year four when I started to organize our “Ducks to the Polls” initiative. Because I’m at a small school and because I was the only political science faculty at the time, I sort of got told, you’re going to be in charge of doing voter registration drives. You’re going to be in charge of taking students to the polls. And then we’d have a little ice cream party after to celebrate their first time voting.

And without fail, every time we do this, we have multiple students who are turned away because they’re either not registered to vote or they’re not registered in this county and they didn’t know that. And that doesn’t feel good. They like to think they’re going to do this like a big adult thing, be with their friends, participate in democracy. But then they’re like crestfallen and they’re a little heartbroken because someone didn’t explain the rules to them. So I set out with six research assistants to sort of figure out what is the lay of the land in terms of what’s getting taught in schools. And in that work, we realized It’s very hard to get all the requisite information done in the school environment that we have today. And that’s why it became a parenting book. So we looked at a lot of different metrics. When we looked at curriculum time from K through 12, we looked at curricular design from every 50 states. We looked at things like the nation’s report card that check in at eighth graders and sees who’s proficient, who has a basic level of knowledge, who has an exceptional level of knowledge. We looked at AP US test scores, which is just an assessment of the top high schoolers who think they know these subjects, and we found that they we’re lacking in every single indicator. We know that we’re lacking in youth voter registration and youth voter turnout. But part of that is because our children are not equipped with the tools to understand the systems that they’re graduating into. And you asked how we got there. And the truth is, there’s a lot of different ways why we got there. The first thing is, understanding the government is hard. There’s a lot of different systems. There’s a lot of different players. There’s a lot of different concepts. And while we teach government and civics and politics in a different way in every single state, there’s sort of a modal form of delivery that happens in a lot of places.

Usually, in your seventh or eighth grade, you’re going to get a class that’s called U.S. History or World History or something that’s Social Studies. And that’s when children are first introduced to sort of the concepts of the founders, maybe westward expansion, maybe American exceptionalism. And then we wait again until your second semester of your senior year of high school and we teach you a class called Government, which is like you know registering to vote, um maybe a few other foundational pieces. But oftentimes, in both of those years, we teach this as a spectator sport. We teach it as a history. We say, here’s the founders. Here’s the ideas they created. Here’s the system that’s in place today. And we don’t, as often, teach it as something that we’re active in, that we change, that we can contribute to. That’s not to say that doesn’t happen everywhere. There are some states that have bright spots or initiatives that are happening. But on average, we are letting our students down.

08:13.60

Lindsey Cormack

It’s also something where you brought up ACT and SAT t scores, and that’s true. When we have this obsession with making higher scores for all of our students and higher aggregate scores for our schools, neither one of these tests has a civics component. So in a compressed classroom day, you’re going to have things that get squeezed out. And when we were interviewing teachers, we know that the things that get squeezed out are the things that aren’t tested. So civics gets to the side.

If you look at the dollars that we spend on these things for every $50 that goes to stem in a K through 12 curricula, only five cents goes to civics. So we know the indicators and the metrics of prioritization just say that we’re not doing enough of this. There’s also the school constraints that our administrators and teachers that we talked to said where they were worried about what parents would think.

Like, they want to teach our kids how to understand their systems. They don’t have enough time, they’re not supported, and they’re afraid that parents are going to think that they’re indoctrinating their kids or brainwashing their kids, they get mean emails, their principals get on them for it, and so they’re just more hesitant to do it than they’ve done in the past.

And so this became a book to say, look, we all want our kids to be as healthy as possible, as successful as possible, as understanding of their own world as they can. But if we really want them to understand politics and government, we’re going to have to do some of that work at home because it’s not happening in schools. It’s not to say that it can’t happen in schools, but currently it’s not.

Scheer:

Okay, well first of all, if it only happens at home, we’re prejudicing the electorate because, and this is was the problem before the explosion of public education, people who went to private schools, privileged schools, privileged colleges got a heavy dose of civic responsibility because they were being trained to be the leaders of the future. So someone who went to, you know, Groton and then went to Harvard and everything,

They actually had the idea that maybe there’ll be a senator or even president and so forth and so forth. What happened, however, with the turmoil of the 30s and the depression and the war and so forth, but actually quite a bit earlier with mass society, there became a sense that no, the public needs to be involved. Ordinary people need to be, they have to have agency and knowledge. And a key object of public education, going back to the beginning even with the founders, some of them supporting it, was you can’t have a significant representative government and governance or a democracy, let alone if people don’t know how the system works. And more important, something that I want to discuss in relation to your primer critical thinking about it, policy, and who does it benefit, and how is the game rigged? After all, you have a nice structure of these separation of powers, but what about lobbying? What about money? And so forth.

It seems to me, I don’t have your expertise on this, but I’ve read a lot about how textbooks got written and all the pressures and everything else. In that heyday of public education, and that includes the state universities, places like the California education system, community colleges and everything else, there was a felt need to do something other than just learn how government works, but to use critical thinking, to think about social issues. In part, this was a response to war, and to the civil rights movement, to gender discrimination, to the role of women and so forth, that a proper education would require critical thinking about your society and how you relate to it. That became threatening.

Because after all, students might also protest. They might challenge policy. They might come just from parents. It was from an establishment that said, wait a minute. And I know you’ve done some work on the Black Lives Matter movement. I looked that up.

And so, you know, suddenly, wait a minute, we don’t want all this energy at these schools. We certainly don’t want critical thinking that challenges the establishment. And the big emphasis on a notion of the meritocracy and these exams you’re talking about really was to get good workers, primarily for industry, who could fit in, that’s where STEM and everything was, and this idea of an engaged citizenry was abandoned. And the only thing I want to take issue with you on is the idea that it can effectively be done in the home across class, across race, across region. Unfortunately, I think the more affluent families, the more highly motivated the parents who have more time to spend with their children, they’ll do it.

But kids who are requiring their school, their public education to give us knowledge won’t be getting it. That’s not your fault. I’m applauding your effort to raise these issues. But it seems to me in your book, you call attention to really a startling failure of our society.

Cormack:

I think that’s right, and I agree with you that there are going to be class differences, race differences, regionality, and people with more time are going to be able to do this. The point of this book is not to say this shouldn’t be done in schools. In fact, if I could wave a magic wand, we would teach civics like every other subject. It would start in kindergarten, build into first grade, second grade, third grade, all the way up to 12th because you know it’s hard to understand this stuff. There’s like past history to understand current events, future ideology, things to consider. There’s a lot that’s hard to get here and so I think it would be great if we could do it in schools. That would be wonderful for me, but I know that right now.

Scheer

And it was done. The point I’m making, it was accepted that it would be done. I think if you went to Iowa State or you went to Michigan State or something, wherever you went, you know the land grant colleges and so forth, that was built in. It was built into the obligation of these schools to prepare you for citizenship. The fact that it’s not there now, I think, represents certain political influences and the abandonment of education by our political establishment that maybe you really don’t want a lot of questioning children of farmers or factory workers.

I mean, it’s a possibility, but wow how could it otherwise happen? Why would it even be controversial not to be talking about the very political system that you’re proclaiming to the world as the way to save us?

And then as you point out in your book, we end up with the kind of presidential elections we have now, which are exercises in madness, stupidity, yeah you know and demagogues and so forth. Well, it’s almost by design.

Cormack:

You’re right. It is a political decision. All of these decisions are political. Like what we’re going to teach in schools, that is a political decision that some entity makes for its own sort of locality and changes or states do that. And we see this today. State legislatures are increasingly exerting oversight on how these types of topics can be addressed in the classroom or if they can be addressed at all. So we have legislators saying in Texas, we used to have something called action civics in some parts of Texas, which would mean in high school group work, in a group of like four to six kids, they’d go find something in their neighborhood that they wanted to be better. Like maybe they’d like better sidewalks, maybe they’d like a basketball court or whatever. And then they’re meant to go figure out who do you talk to about that? Is that like a parks and recreation department? Is that a city council? Is that a government manager? Whatever. They’re meant to figure that out.

And they’re meant to create some sort of action proposal for how they do that. Now, they’re often not going to win. They’re not going to get the change that they want. But in that critical engaging with how does this process work and how do I experience it, they learn a lot more. But state legislatures have said, you know what, that’s too political. That means there’s people in school talking to elected officials or talking to appointed officials. We don’t want action civics. And state legislatures are increasingly making choices like this.

Which is why, if we want our kids to know these things, we have to create opportunities for them to do this, and not rely on schools because increasingly, it’s just not a place to get this done, despite the fact that it could be.

Scheer:

But see, that’s the statement I’m trying to challenge. I believe you can’t, yes, it’s admirable that you would write this book and get parents to do the right thing by their children and by their society. But in order for a society to be healthy, its main structures, certainly of education, have to be healthy. And you know, you can look at totalitarian societies and say, well, they consciously make their students ignorant or avoid important questions or controversy or critical thinking. And that’s in their interest. We are doing a variant of that.

If we don’t, for example, I mean just let me get to the substance of your book, and you lay out the whole structure and in the Constitution and so forth. And I kept thinking, when I went to City College, which is after all this progressive education, this course we had, Basic Issues of American Democracy. And Bishop and Hendel was the textbook. Hendel was actually in our department of City College, in Columbia as well. But it was a famous textbook. Others, Charles and Mary Beard, The Rise of American Civilization. There were these monumental books that dealt with the controversies of life, which is one way to get students interested, right? And so for example, when I was there, a question would come up in my early editing. Why is baseball racially segregated? We just fought a war for democracy. And, and you know, until Jackie Robinson came in, and why was the US military racially segregated in a war for freedom, you know, and you can go I kept thinking reading your thing. If I were the child, and for instance, you get to the part about when women get the vote. If this was such a wonderful democracy, how come, you know, maybe young Mary said, well, how come my brother Jim would be able to look forward to voting? But it wasn’t until 1920, after all of this history, that I could vote as a woman. Right. Without that kind of discussion, the structure is just a facade, separation of powers, right? Respect for individual freedom and all that, but it’s a joke. In fact, let’s just go cut to the chase. For instance, one question I would have, I wrote down all these things a child might ask.

If I were doing this, and I have raised a few children myself, okay? I would say, here’s what the young child says in one of your things. Mommy, what is genocide? Because of the internet now and news and everything, we hear about it. And she said, you know, Jimmy says that his mother says that what we did to Native Americans was genocide. And she says it’s now also going on in Gaza, Israel, war.

What is genocide and and did we, did these founders, are our country, was it built on genocide? As the mother, what would your answer be?

Cormack:

Well, so it depends on where you’re coming from. There’s plenty of moms that I know who would say they don’t have a firm grasp of that. And instead of lying to your child or saying, I’ll tell you when you’re older, I think the answer is to say, you know what, I’m not sure of that definition. Let’s go figure this out together. If I was coming at it at a point where I didn’t know it. I think the behavior to model information seeking is to say like, okay, let me go learn a little bit more.

Now if it was a topic like this where I felt decently well versed and thought I could have a conversation without having to go look up some information right then, I’d engage in it. And so the first question that I always ask my daughter or that I ask in my class if people come to me with something like this is, what have you heard about that?

And the reason that I like to start a conversation with that is it lets us set the table with what they have heard because it’s going to be different than what I have heard. Our inputs are going to be different and I want to be able to have a conversation with someone that respects their starter knowledge and then I get into it with what I would have.

And these are tricky questions. These are hard. And especially if we think about like, did we found the greatest country on earth, but did we do it in a way that was terribly detrimental to people who were here before? The answer can be yes to both. And I think holding those sorts of things where it’s uncomfortable, but there’s truths in different components that doesn’t make it one clean story, that’s sort of the work of what we have to do here. We have to get into the nuance. We have to be willing to see it from different perspectives.

And I think that is something that only happens in a back and forth iterative discussion with your child or really anyone that you’re doing this sort of work with. And so that’s how I would approach it. If I didn’t know it, I’d try to seek more. If I did know it, I’d start with this, what have you heard? And then move from there.

Scheer:

But then I’m going to go to a slightly older trial, maybe already in high school or something, or junior high school, and they said, look, ah you’ve been telling me about the founders and this great document of the Constitution and separation of powers and judicial review and so forth and so on and everything. How come these people, some of them were slave owners?

There are quite a few. How come slaves? And you say this was a great democracy, but it was built on slavery. And again, getting back to this gender thing, how come women couldn’t vote and it took another 100, what, 20 years or so forth before you could get to vote or more? And they raised those questions. So what I missed in the book, frankly, was a recognition of the importance of critical thinking to education. And I’m a teacher at USC at Annenberg and actually our theme. I don’t know how often we refer to it in our school of communication is supposed to be critical thinking over in journalism, it’s empathy, but on both those considerations. If these founders and the system they created provided checks and balances, why didn’t it provide a check against slavery or male dominance or that only wealthier people could vote? Where was the wonder of this Constitution that you spent a lot of time in this book celebrating, right? The brilliance of it actually. And then the question a child might ask if it was so great, how come it didn’t interfere with slavery? How come it didn’t give women the vote? How come it didn’t allow working people or poor people to live better and to participate? What would the answer of a parent be? Why are we celebrating it if in fact it didn’t check slavery or exploitation of workers or male hegemony?

23:19.46

Lindsey Cormack

Yeah, these are big and hard complicated questions. But these are the kinds of things that I think makes politics something that allows for critical thinking. It allows you to develop these non-cognitive skills where you’re not just, you know, recalling facts, but you’re saying, okay, how can we fit these disparate things together? And the way that I sort of think about it might be the way that um the people who are like stewarding James Madison’s Montpelier kind of think about it, which is look, two things can be true. This can both be an innovative foundational document that has provided the best sorts of decision making process for not only the United States, but been exported to the world in the form of some sort of Republican representative democracy. So it’s provided a very good roadmap for grappling with really hard things like workers rights, like slavery, like women’s rights, but it doesn’t get everything right at the get-go. And that’s also true. So it can be something that we celebrate to say, look, it’s been the best roadmap that we have known to date, but there were problems in how it’s created. There were things that were difficult. And I kind of think about it as we maybe should de-center a little bit the founders as like, oh, these are the end-all, be-all people to do this, and also elevate the enslaved community and the enslaved legacy, which is if not for these people, the people who are writing wouldn’t have all the free time, the wealth, the education to do these things. So we kind of have to see them both as valuable in American history because they truly are. And so I think these sorts of questions are stuff that lets you get into things that are hard with your kids, and you’re not just calling back a fact, but you’re saying, okay, let’s think about this from a few different perspectives. Is there a way to see some positivity in this despite the fact that it’s overwhelmingly negative in some ways? That’s that’s how I would approach that subject with a teenager.

Scheer:

But in terms of this model of ours, and yes, a lot has been written celebrating it, but people have developed other models in the world. One of the problems we have is sometimes we don’t seem as sensitive to their right to have different models. So for instance, there’s a lot of countries in the world now that their model is basically built around anti-colonialism.

And these are countries actually founded after World War II, a number of them and so forth. And they stress other notions of obligation to their citizenry. But even before that, you had the French Republic, you had the Roman Senate, you’ve had lots of experiments and governance. And picking up on something you said before about American exceptionalism.

One of the things which we see in our election is a constant assertion that we have the secret sauce. Donald Trump, I’m going to make America great again. And then Hillary Clinton responds, oh, no, America was always great. That was, to my mind, one of the most clarifying and yet stupid exchanges in American history.

Was it always great when it had slavery? No. But that language, which seeps through some of this patriotic assertion about our system that is so unique and answers to questions, we’re living at a time where, hey, it hasn’t turned out to be so great. In fact, half the country thinks if the other party wins, the country’s going down the tubes. That’s the way I look at this election. Oh my God, if Trump should win, we’re at the end of democracy. I think Kamala Harris even says things like that. On the other hand, Trump says if a socialist or communist, if Kamala Harris wins, the Democrats are going to destroy the country. I’m here to save you. So we’re at a moment where basically both political movements are denying that our Constitution has saved us from madness. They’re saying, despite our Constitution, we’re in a moment, we’re a banana republic right now.

Cormack:

Yeah, I think what I would say is two things. One is that I do sort of disagree with this premise. I think the American people have been fed this sort of like we’re on the precipice of something really bad for a long time. And it’s not clear to me how much longer we’re going to swallow that narrative.

But the second thing that I would say to this is that If we think that everyone who disagrees with us is either like a dummy or evil, we know that those can’t be true because they will think the same things about us. And so what we could better do is to understand the limits of our government. We should understand the levers of power that we can pull, so that we are not as easily frenzied by these accusations, so that this sort of media is not compelling both in the traditional form and in social media. Like the more we understand where the limits are, the better we will be because we can take the temperature down. And that’s why I think we need to have a bigger focus on learning about these things from beginning to end, because it’s hard for misinformation and disinformation to thrive if people understand the basics.

Scheer:

Yeah, let me say, by the way, I applaud your effort and I’m not just pandering to you. No, seriously, because in my own teaching I taught yesterday I teach hundreds of students all the time. I do refer to the founding documents, because they are a great organizing principle. They raised the fundamental question. I go back to George Washington’s farewell address, where he warned us about empire, even though we were going to build an empire in North America and destroy everybody in our way, including a good chunk of Mexico.

But nonetheless, he was aware we have to spread our influence by peaceful means, you know and warned about the impostures of pretended patriotism. And then, of course, I deal with the Fourth Amendment to try to understand the internet, understand somebody like Julian Assange being in jail at our request, even though he seemed to be ah actively working to make the Fourth Amendment and the First Amendment a reality. Yes, I agree with what you said that we have this document that raises all of the important questions. I think everybody should, but where we’re disagreeing and it’s not your fault. I think if it falls upon the parents to do this education, we are really in big trouble, that a society has a responsibility to educate its young, its people, to function. And particularly if it claims to be a representative governance, this is not your fault. you’re really out there. And let me just praise the book in important ways. I think as a political scientist and as a writer, you make the Constitution very accessible. You make our system of government very accessible. If I were to recommend or look for a book tell me about all the amendments, tell me how history was constructed. And do it in less than 300 pages or something of a very clear language, very accessible not just you know for a college student but for maybe for an eight-year-old or a 12-year-old and so forth, you’ve done it okay and the book is by the way let me get the title out here “How to Raise a Citizen” it’s by Wiley Publisher, so I want to say this is a book that’s worth buying worth reading worth sharing with your children. Nothing in my nitpicking here should detract from that. I just want to be clear about that. Your command of it, you know your history, and it’s very accessible. That’s the word I would use without cheapening it. It’s a very good discussion.

What I object to, really, is, OK, this is great, but it’s not going to come from parents. And it’s not going to come from people like you. And it’s not your responsibility. And it’s not the responsibility of parents. After all, that’s why we spend all this time on education and money. That’s why we require people to go to schools. And if they can’t learn how power works, let me just take it a little further, and because we’ll probably run out of time here. Your book is sort of a take off.

And I would hope then the children would say, yeah, but but mommy or daddy, but what about these things called lobbyists? And what about the role of money? And isn’t it all rigged? And so let me bring it, not maybe not the engineering students at Stevens, but I have a very positive view about our students, not just at USC, but I’ve also taught at UCLA and other places.

Because of the internet and because of the controversies in society, you can actually get them up to speed very fast if you say, well, yeah, the Senate sucks. Look at it. As you discuss in your book, the representatives, two for a state and population difference and so forth. How did you get there? Well, maybe he got there because privileged people wanted, but then how do you change it? What are the limits of the system? And then you send people, say, instead of just shopping on the internet or with your laptops in front of you, actually, why don’t you do some research on this? Or what do reformers want to do, including what can we do about the Supreme Court? Should it be expanded? I guess what I’m saying is, I find democracy has to be taught not as a set piece, but as a center of change and controversy.

And again, I’m not holding you responsible or the parents. That seems to me what a healthy educational system would make front and center, not some minor part of it. And that’s why we’re in trouble. The reason I wanted to talk to you is I think you’re putting your finger on the main reason why we have madness now. Basically, we’ve celebrated something called representative government and democracy without really teaching it or examining it or holding it up as a responsible exercise. That would be my pitch.

Cormack:

I actually think I agree with you on a lot of this. I think it is an injustice and a disservice to put a child through a K through 12 schooling environment, especially in a public taxpayer funded schooling environment and not let them know with certainty the government that they are graduating into and how they can influence it. That is a disservice to them. No one is better served by that. I do think that if I could wave a magic wand, it would happen in schools. But I do know that there are limits right now and my hope is eventually by isolating this and saying, like, hey, everyone, we have a problem, and it’s not going to get better unless we decide to do something differently. Do parents solve everything? No. But do enough parents who see that there is a problem, who want schools to get involved, to have the power to lobby for school boards or to be in state legislatures to change this? I think the answer is yes. But it’s not clear how we get that ball rolling unless we point out the problem, which is our kids are not learning this.

Our politics will not feel or function any better if we keep thinking someone else is going to come save us because no one’s coming right now. So as the adults in the room, I think we have responsibility to point these things out and try to make it a little bit better piece by piece, hoping and knowing that a fuller solution would be an optimal outcome, but to get there is going to take incremental efforts.

Scheer:

Yeah, so I’m going to end with one thing and I agree with what you just said. I think, in part, it’s by design. I’ll just give you that people of power really don’t want the system to work because when it works, it often is uncomfortable to them.

People can use the system to bring about change. And one thing that bothered me on page

shed light on why these instances are not violations of the First Amendment. And it spills over into your discussion of the national security state and so forth. And it seems to me the main drama in regard to our founding document, and this is what Washington warned about in his farewell address. When you become an empire or when you are expanded all over the world and when you’re pretty continuously engaged in wars where truth becomes a casualty and so forth, it seems to me the checks and balances and the brilliance actually of the American Constitution, I’ll use that word, assumes a civil society that is not dominating other people or waging war or saving them. It assumes that you are basically dealing with your problems, your issues, and this idea of overclassification. I mean, as a teacher, it seems to me most of the subjects we have to deal with, whether the start of the Iraq War or Vietnam and the Gulf of Tonkin or any of these things, we’re basically trying to figure out what do we know? How do we get the information? It’s denied to us and so forth, right? And I just wanted to raise that question, because it runs so, so through the book. Are we not expecting these kids to learn when in fact the system doesn’t want people. For instance, okay, one last point. I’ll be upset if I don’t raise it.

You mentioned the economy. I mean, you have a number of things, things we have to teach, why they’re important. The big thing that happened in our economy was the deregulation of Wall Street beginning in 1980. We have a growing class, a difference. We have people who will feel estranged from the economy, so they vote for a faux populace, and so forth. And for people of power, that’s a comfortable situation, right? You can sell liars, loan mortgages, you can do things. So, you know, I look at you as the good citizen, raising good citizens. Then I look at all of these manipulators out there, these hustlers, these demagogues, people selling snake oil. And those are the people who really don’t want an educated citizenry. And that happens throughout the world, right?

Cormack:

I think that’s absolutely right.

Scheer:

You’re a political scientist. I’m going to let you take as much time as you want to tell me I’m wrong or how you see it.

Cormack:

I think you’re right. I think we know that governments are less accountable when their people do not understand what’s happening. That’s not even for government. That’s anything. If there’s an information asymmetry, whoever holds that information gets to act with more leeway and there’s no way to hold them accountable.

And so for people who are frustrated with government, as many of my friends are, I think the thing is not to lean out and assume that something else is going to fix it, but to lean in and recognize that governments can operate with more expediency for the ends that they want, not necessarily the ends that we want if we do not know how to hold them accountable. And that is what it is to participate. That is what it is to understand what news stories are worth your attention and what is fodder or distraction. And so by understanding these basics, by being more rooted in our system, I think you are far more able to create a representative government that you can hold accountable versus if you just pay attention to it on occasion or whatever happens to be in your social media feed. So I think it’s about recentering this as an important life skill that we should want in our schools, in our homes, and something to aspire to instead of thinking someone else is going to do it.

Scheer:

Amen. But we can take it one favor and say, yes, you should do it. And you should encourage your neighbors to do it. But you should also demand that the people who control school budgets and control education, including on the college level where we have a new idea, now let’s not have too much controversy. Let’s not have disturbance. Let’s you know all be nice and so forth rather than confront issues that we have.

It seems to me, I don’t want to hijack your message here. Yes, do it at home. Yes, do it with your children, but also demand that it happen in the schools.

Cormack:

Yeah, I think that that is the symbiosis that I hope for. I think we agree there.

Scheer:

Good, that’s good. So, the title of the book is “How to Raise a Citizen (And Why It Is Up to You to Do it). Yes, it begins with you, but maybe you can also call your congressperson and demand that they get on it, or these state legislatures. All right, well thank you for doing this. I want to thank Christopher Ho and Laura Kondourajian for posting these shows on that great NPR station we have in Santa Monica, KCRW, and other NPR stations. I want to thank Joshua Scheer, our executive producer, who once again knew about your book, insisted I do it, and really bugged me to do this book, and I’m happy I did. And believe it or not, even though I teach the stuff I learned from the book about your examination of structural government, you make it very accessible. It’s a very good primer. Put that out there. Diego Ramos, who writes the introduction, Max Jones, who does the video, and the JKW Foundation in memory of a very important writer and public intellectual, Jean Stein, for giving some funding, as does Integrity Media Foundation, helping us put these shows on. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

https://scheerpost.com/2024/10/04/everything-your-kids-wont-learn-in-school-about-our-democracy-can-parents-fill-the-void/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

teaching bits...

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

Kurt Vonnegut, Mother Night

We study American history for important reasons. We study because it helps us understand how events in the past continue to influence the present. We study because American history tells us who we are.

Yet teaching a full and honest history is much more difficult than it should be.

There are history textbooks that ignore the fact that white elites grew rich off the labor of the enslaved. There are textbooks that continue to minimize extraordinary struggles for universal suffrage. There are textbooks that fail to examine the long-term effects of forcing Indigenous young people into off-reservation boarding schools.

There are many people who want to hide parts of the past, by distorting it or simply making it disappear. There are those who want to prevent classroom lessons that they claim might cause some to experience discomfort, guilt or some other form of “psychological distress.”

I taught American history in high schools for more than three decades and, for the most part, I used approved textbooks. I often struggled with how the material was presented and I struggled with what was left out, but I continued using the texts.

An extensive 2024 report by the American Historical Association found that with the increasing availability of technology, some instructional materials and student assignments have moved online, but hard copy and digital textbooks continue to be used in 87% of high school classrooms.

In much of the research on what students know about American history, it is the textbooks that are blamed for most of the deficiencies. As a retired educator, I finally have time to puzzle out what I had to deal with, and it has motivated me to write a series of ScheerPost columns on what I call “Missing Links in Textbooks.”

In writing about what textbooks ignore, I have discovered that neglect of uncomfortable information can be limitless. That has led me to wonder why high school history textbooks are so different from the written work of real historians. Are the textbooks really meant, as Frqnces FitzGerald wrote, only “to tell children what their elders want them to know?”

The act of writing about what essential information is missing has led me to ask why. As a result, in my last column, I looked less at what is missing and began to focus on why the textbooks miss so much of what I consider essential.

I even asked myself if textbook publishers alone could be responsible for presenting such an incomplete, and often boring, history. Perhaps there is something more fundamental. Perhaps there is something all textbooks have in common. It turns out that it was obvious from the start. High school textbooks are simply an end product in a long complex process.

The Standards Came FirstHigh school American history textbooks must meet state standards in order to be approved for classroom use, and those standards are only meant to determine what is minimally required. Textbook publishers can go beyond the required material, but very few do. Why risk controversy? Why risk losing sales?

Taken together, the California Content Standards provide the “what” of an instructional program, and the California History-Social Science Framework helps flesh out the “how.”

After reviewing the documents, I was surprised by how minimal they are. But minimal or not, I now believe that many, if not most, of the missing links I have identified in the textbooks are rooted both in the standards and in decisions by publishers not to do more than is required.

California’s Content Standards, adopted in 1998, and the California History Social Science Framework, adopted in 2016 together are quite large. To facilitate comparisons between what is missing in the standards and textbooks, I refer you to three previously written ScheerPost articles I wrote on Indigenous Peoples, Women, and the roots of the Vietnam War.

In case you want to download the Standards and the Framework and use them along with what I have written, I have indicated the page numbers for both documents in the text of this column.

Indigenous Peoples in the California Standards (CS) and the Framework (HF)Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race.

Martin Luther King Jr. Why We Can’t Wait 1963

In Missing Links in Textbook History: Indigenous Peoples I wrote that knowledge of the historical relationships among Indigenous Peoples and the United States is vital to understanding who we are as a nation. I found that the textbooks tend to explore U.S. history by relegating Native Americans off to the side or by ignoring them altogether.

In the Content Standards (CS) for high school, the term “Indigenous Peoples” is not found, but the term “Indian” is scattered throughout lessons at different grade levels. In the history standards, there is very little focus on Indigenous Peoples other than the requirement that high school American history students “discuss the relationship of the American Indians to the Civil Rights Movement of African Americans.” (CS page 53) Here is that standard exactly as written:

Discuss the diffusion of the civil rights movement of African Americans from the churches of the rural South and the urban North, including the resistance to racial desegregation in Little Rock and Birmingham, and how the advances influenced the agendas, strategies, and effectiveness of the quests of American Indians, Asian Americans, and Hispanic Americans for civil rights and equal opportunities.

As in the Content Standards, the word “Indigenous” in the high school History-Social Science Framework (HF), is replaced by the word “Indian.” Consistent with what is in the content standards, the first mention of Indigenous people in the high school history framework is in the context of the Civil Rights Movement.

It is written (HF page 416) that, due to the existence of the Civil Rights Movement, “American Indians … became more aware of the inequality of their treatment in many states where Indian tribes are located.”

The very idea that Indigenous Peoples became “more aware” of unequal treatment because of the Civil Rights Movement seems unlikely. I am certain that most Indigenous Peoples were well aware of their unequal treatment, but they were also likely to regard any successes of the Civil Rights Movement as compatible with the actions described below.

American Indians engaged in grassroots mobilization as follows:”… from 1969 through 1971 American Indian activists occupied Alcatraz Island; while in 1972 and 1973, American Indian Movement (AIM) activists took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C., and held a standoff at Wounded Knee, South Dakota.” (HF page 419).

Significant to me is the fact that nowhere in the high school standards is there mention of the series of massacres that plagued the Indigenous Peoples. The only mention of these massacres is in the standards for fifth grade (CS page 17). Nowhere in the high school standards is there any specific mention, for example, of coerced attendance at American Indian boarding schools meant to culturally assimilate Indigenous children. Nowhere in the standards is there mention that such coerced assimilation is a form of genocide.

Of course, a complete history would include all of that and more, but it is not a requirement.

American Women in Content Standards and the FrameworkIn that solemn solitude of self, each soul lives alone forever… Who, I ask you, can take, dare take, on himself the rights, the duties, the responsibilities of another human soul?

Elizabeth Cady StantonBefore the Congressional Committee of the Judiciary Jan. 18, 1892

It is no secret that the stories of men dominate almost all recorded history. Unfortunately, male dominance is also found in the Content Standards, explained in the framework, and then written into the textbooks.

In my article Missing Links in Textbook History: Women I wrote that throughout American history, women have been overtly excluded, by law and custom, from participation in many areas of life outside the home. I also referenced an article published in 1975 by Phyllis Arlow and Merle Froschl, “Women in High School Textbooks.” In it they examined the content of 14 textbooks for coverage given to women and found that even in areas where women played important roles, they remained anonymous.

The Standards continue the practice of ignoring the laws and cultural traditions that excluded women from participation in so many aspects of life. And again, what is neglected in the standards is neglected in textbooks.

According to the Sacramento County Office of Education the standards are “designed to encourage the highest achievement of K–12 students by defining the knowledge, concepts, and skills students should acquire in each grade level.” Here is what I found that defines “the knowledge, concepts, and skills” that students in high school are required to learn about the roles of women in American history.

The Standards require that students analyze the passage of the 19th Amendment and the changing role of women in the society that followed. They are also required to discuss … the roles of women in military production and to describe the changing roles of women as reflected in the entry of more women into the labor force in the 20th century. (CS pages 47, 51, 53)

That is the extent of what is required, but again, the textbooks could have included more, such as the laws and traditions that restricted women’s participation in American life. At the very least, the standards should have required teaching about colonial laws of coverture which remained in place after the American Revolution and meant that when women married, they lost their legal identity. They could not own property, control their own money or sign legal documents.

The Standards should also have required teaching how, before the establishment of women’s colleges in the U.S. in the 19th century, higher education was almost always exclusively for males. For more about “the changing roles of women” in the United States, please refer to my article here.

In a section in the History Framework entitled “Industrialization, Urbanization, Immigration, and Progressive Reform,” there is a list of four questions that high school teachers are invited to focus on while teaching the early years of the 20th century, generally called the “Progressive Era.” This is how one of those questions, focused on women, is introduced:

“This question can frame students’ exploration of the women’s suffrage movement: Why did women want the right to vote, and how did they convince men to grant it to them? (page 381).

I was puzzled by the first part asking: Why did women want the right to vote? After all, one would think the answer to be obvious. Nevertheless, in the framework (on page 388), the explanation of how teachers might approach the question begins by saying that women wanted the vote because of progressivism: “Because progressivism called for an expanded government to protect individuals, it is only natural that expanding voting rights were deemed equally important.”

I wish I could make sense of the suggestion that ” progressivism” is what made women want to vote, but I can’t. In the real world, well before the Progressive Era (usually considered 1900 to 1929), women, and women’s organizations, were working for social reform. Women’s clubs across the nation were working to promote suffrage, better schools, the regulation of child labor, and prohibition.

Well before the Progressive Era, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton called a women’s convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Delegates to that convention stated in writing, in 1848, that “all men and women were created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights.” Then, in a list of male-imposed abuses, they noted that men had compelled women to submit to laws in which women had no voice in adoption.

At least a decade before the Progressive Era, Susan B. Anthony was arrested and tried for voting in the election of 1872. After her 1873 conviction she addressed the court explaining to those who would listen: that it was, “… we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union …”

But the Framework suggests that it was because “progressivism” called for “expanded government” that women were inspired to want voting rights. If students had been prepared properly, they would have known that many women demanded the right to vote because they were citizens with “unalienable rights.”

The second part of this same “focus question” is worse than the first: How did they (the women) convince men to grant it (the vote) to them?”

Again, if prepared properly the students would already know that the women did not change the situation by politely saying “please.” They repeatedly demanded their right to vote.

Some organized, like Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Some voted illegally, like Susan B. Anthony and then lectured a courthouse of men when given the opportunity.

Some organized, like Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, who founded the National Women’s Party, picketed the White House and were arrested. Some went to prison with Alice Paul, who had organized a hunger strike to protest their illegal imprisonment and was force-fed through tubes.

All of these women refused to be ignored. They had no choice. In the words of Rose Schneiderman (union organizer, feminist, and a founder of the American Civil Liberties Union): “We must stand together to resist, for we will get what we can take — just that and no more.”

If the point of the standards and the framework were really to educate “critical thinkers,” one of the four questions that should have driven this unit should have been: Why did the majority of men want to deny women the vote for so long, and how did women organize to force them to see reason?

The Vietnam War in Content Standards and the FrameworkDo you hear me when I say this war is a crime? When I say I am not as bitter about my wound as the men who have lied to the people of this country? Do you hear me?

Ron Kovic

Speaking outside the Republican Convention Miami Beach, Florida 1972

In my article on Missing Links in textbook treatment of the Vietnam War, I suggested that to understand events in Vietnam, students need to understand both the long-term Vietnamese-nationalist struggle against France and the working relationship between the Viet Minh and the American OSS during WWII. Neither are required by the Standards or the Framework and neither are in the textbooks.

In the Content Standards it is stated that students be required to “analyze U.S. foreign policy since World War II.” The specific requirement is that students should be able to “trace the origins and geopolitical consequences (foreign and domestic) of the Cold War and containment policy.” However, that complex requirement simply ends with a list of U.S. foreign policy events since World War II. (CS page 51).

That list is followed by the requirement that students “Understand the role of military alliances, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), in deterring communist aggression and maintaining security during the Cold War.” The suggestion that SEATO actually deterred “communist aggression” rather than providing an excuse for the U.S. to prevent a unified Vietnam is purposely misleading.

When SEATO was created in September of 1954, its members were the United States, France, Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Thailand and Pakistan. Only two members were in Asia.

SEATO expanded the concept of anti-communist collective defense to Southeast Asia regardless of whether a nation or a territory was a member. In the Content Standards the connection between SEATO and Vietnam is left unexplained. And that explains why it is usually unexplained in textbooks and clearly not understood by students.

According to the U.S. State Department, as the conflict in Vietnam expanded, Vietnam, although not a member, was considered under SEATO “protection,” giving the U.S. a legal framework for continued involvement. “The United States government used the organization as its justification for refusing to go forward with the 1956 elections intended to reunify Vietnam.”

None of this is in the Standards and, as a result, I have never seen any of it explained in an American history textbook.

The first time Vietnam is mentioned in the Framework is on page 408. “Foreign policy during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations continued Cold War strategies—in particular, the ‘domino theory’ that warned of the danger of communism rapidly spreading through Southeast Asia.” This claim is an attempt to mislead.

Certainly, the domino theory was a “Cold War strategy,” but it required acceptance of a convenient, but mythic, monolithic communism. Evidence, even at the time, made it clear that communism in Vietnam was nationalistic and not a product of Soviet influence.

I would argue that mentioning the domino theory as a warning against rapidly spreading communism is an attempt to suggest causation without evidence. In other words, it is an attempt to suggest that communism was a Soviet virus, Vietnam was susceptible, and therefore American intervention was necessary.

Use of the domino theory, I believe, was a scare tactic, but at the very least its accuracy is debatable and debate is fundamental to any history course. The framework ought to encourage it by outlining that debate honestly and requiring it be discussed in classes.

Immediately after mention of the domino theory, the Framework requires that students be taught “how America became involved in Southeast Asia, particularly after the French conceded to the Vietnamese in 1956.” (HF, page 408)

I am not even sure what is meant by “the French conceded to the Vietnamese in 1956” because, in the real world, the French were decisively defeated by the Viet Minh in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu.

The suggestion that students should study American involvement in Southeast Asia “particularly” after 1956, is another attempt to mislead. The Geneva Conference in 1954 would have been more relevant because it led to agreements that Vietnam would soon be one nation and formally ended French colonialism. The 1954 Geneva agreements are not required in the Standards.

Much of this is explained in detail in my article on Missing Links in Textbook History: Vietnam, so I will not repeat it here. Nevertheless, if textbook treatment of the roots of American intervention in Vietnam is based on what is in the Standards, students will learn very little about the American war and nothing about why it failed.

What is History Anyway?Historical writing always has some effect on us. It may reinforce our passivity; it may activate us. In any case the historian cannot choose to be neutral; he writes on a moving train.

Howard Zinn

The Politics of History

I have learned a lot from Howard Zinn, but I do not necessarily agree that it is impossible for the historian to be neutral; I would agree that historians can and should be fair.

In his books, Zinn focused on a wide range of historical issues including race and racism, the power of social movements, the reality of class, and the brutality of war. His histories include stories of people representative of all Americans.

He wrote about the Indigenous Peoples as deserving equal rights. He praised their accomplishments before the colonists arrived. He acknowledges the victories of the labor movement and criticized the excesses of the Robber Barons.

He suggested that the United States entered World War I for political reasons. And he was vigorously against the American war in Vietnam. These may not always be neutral positions, but the way he argued them was always fair.

What Howard Zinn did urge was “value-laden historiography,” not because he thought that historians should determine answers, but because he felt they should suggest questions.

Perhaps, for some of my fellow citizens, suggesting essential questions is the new definition of bias.

I am convinced that neutrality and fairness both have their place in history books and I am certain that the required American history standards as written in the California Content Standards and the History Framework should be both. They don’t come close.

But what might it mean if standards were both neutral and fair? A fair and neutral history, I think, must embrace differences of opinion. A fair history should not put the Indigenous people on the sidelines. A neutral history should not ignore evidence of genocide.

A fair history cannot fail to mention the laws and traditions that have prevented women from participating in so many areas of American life. A neutral history should not ignore the usefulness of the Pentagon Papers in teaching about American intervention in Vietnam.

What I have labeled “Missing Links” in both textbooks and standards refers to information that is both missing or misleading. As such, “Missing Links” define what is seldom taught and therefore seldom learned. History, written with essential information missing, transforms high school history textbooks into pretense, pretending to be something they are not.

I suggest that those who produce standards or publish textbooks or those who teach should insist that an accurate history contains emotion and empathy. More than 2,500 years ago, the Greek historian Herodotus admitted that he was obsessed with memory. He was fearful on its behalf because he felt that it was something defective and fragile.

Today we live with an illusion that knowledge is at our fingertips, but encyclopedias and textbooks are famously unreliable largely because they lack emotion — the one thing that makes events memorable.

If a textbook tells the history of genocide against the Indigenous Peoples, it must convey injustice, pain and suffering, just as textbooks that recount the history of slavery should leave students feeling pain and injustice. These examples of historical events cannot be reduced to dates and places.

https://scheerpost.com/2024/10/20/why-do-approved-american-history-textbooks-contain-missing-links-part-2/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.