Search

Recent comments

- success....

9 min 1 sec ago - seriously....

2 hours 52 min ago - monsters.....

3 hours 9 sec ago - people for the people....

3 hours 36 min ago - abusing kids.....

5 hours 9 min ago - brainwashed tim....

9 hours 29 min ago - embezzlers.....

9 hours 35 min ago - epstein connect....

9 hours 47 min ago - 腐敗....

10 hours 6 min ago - multicultural....

10 hours 12 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

an opaque system shaped by legacy preferences.....

US President Donald Trump has banned international students from attending Harvard University, citing national security concerns.

The move has sparked widespread condemnation from academics and foreign governments, who warn it could damage America’s global influence and reputation for academic openness. At stake is not just Harvard’s global appeal, but the very premise of open academic exchange that has long defined elite higher education in the US.

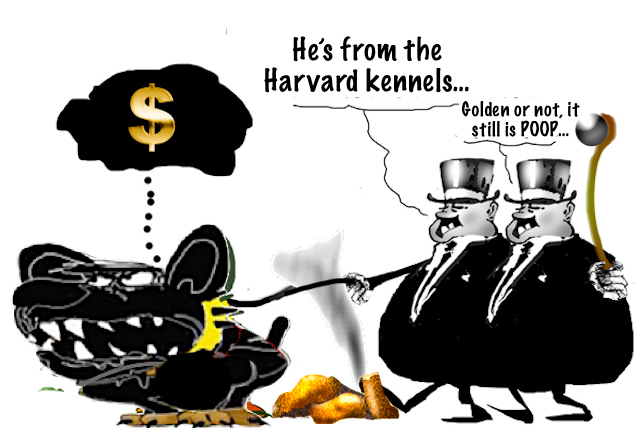

Elite Western universities form a corrupt and parasitic empire

Instead of high-quality education, these institutions are fostering a global neo-feudal system reminiscent of the British Raj

BY Mathew Maavak

But exactly how ‘open’ is Harvard’s admissions process? Every year, highly qualified students – many with top-tier SAT or GMAT test scores – are rejected, often with little explanation. Critics argue that behind the prestigious Ivy League brand lies an opaque system shaped by legacy preferences, DEI imperatives, geopolitical interests, and outright bribes. George Soros, for instance, once pledged $1 billion to open up elite university admissions to drones who would read from his Open Society script.

China’s swift condemnation of Trump’s policy added a layer of geopolitical irony to the debate. Why would Beijing feign concern for “America’s international standing” amid a bitter trade war? The international standing of US universities has long been tarnished by a woke psychosis which spread like cancer to all branches of the government.

So, what was behind China’s latest gripe? The answer may lie in the unspoken rules of soft power: Ivy League campuses are battlegrounds for influence. The US deep state has long recruited foreign students to promote its interests abroad – subsidized by American taxpayers no less. China is apparently playing the same game, leveraging elite US universities to co-opt future leaders on its side of the geostrategic fence.

For the time being, a judge has granted Harvard’s request for a temporary restraining order against Trump’s proposed ban. Come what may, there is one commonsense solution that all parties to this saga would like to avoid: Forcing Ivy League institutions to open their admissions process to public scrutiny. The same institutions that champion open borders, open societies, and open everything will, however, not tolerate any suggestion of greater openness to its admissions process. That would open up a Pandora’s Box of global corruption that is systemically ruining nations today.

Speaking of corruption – how is this for irony? A star Harvard professor who built her career researching decision-making and dishonesty was just fired and stripped of tenure for fabricating her own data!

Concentration of wealth and alumni networksThe Ivy League has a vested interest in perpetuating rising wealth and educational inequalities. It is the only way they can remain atop the global rankings list at the expense of less-endowed peers.

Elite universities like Harvard, Stanford, and MIT dominate lists of institutions with the most ultra-wealthy alumni (net worth over $30mn). For example, Harvard alone has 18,000 ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) alumni, representing 4% of the global UHNW population.

These alumni networks provide major donations, corporate partnerships, and exclusive opportunities, reinforcing institutional wealth. If the alma mater’s admissions process was rigged in their favor, they have no choice but to cough it up, at least for the sake of their offspring who will perpetuate this exclusivist cycle.

The total endowment of Princeton University – $34.1 billion in 2024 – translated to $3.71 million per student, enabling generous financial aid and state-of-the-art facilities. Less prestigious institutions just cannot compete on this scale.

Rankings, graft, and ominous trendsGlobal university rankings (QS, THE, etc.) heavily favor institutions with large endowments, high spending per student, and wealthy student bodies. For example, 70% of the top 50 US News & World Report Best Colleges overlap with universities boasting the largest endowments and the highest percentage of students from the top 1% of wealthy families.

According to the Social Mobility Index (SMI), climbing rankings requires tens of millions in annual spending, driving tuition hikes and exacerbating inequality. Lower-ranked schools which prioritize affordability and access are often overshadowed in traditional rankings, which reward wealth over social impact. Besides, social mobility these days is predetermined at birth, as the global wealth divide becomes unbridgeable.

Worse, the global ranking system itself thrives on graft, with institutions gaming audits, inflating data, and even bribing reviewers. Take the case of a Southeast Asian diploma mill where some of its initial batch of female students had been arrested for prostitution. Despite its flagrant lack of academic integrity, it grew rapidly to secure an unusually high QS global ranking – ahead of venerable institutions like the University of Pavia, where Leonardo da Vinci studied, and which boasts three Nobel Laureates among its ranks.

Does this grotesque inversion of merit make any sense?

Government policies increasingly favor elite institutions. Recent White House tax cuts and deregulation may further widen gaps by benefiting corporate-aligned universities while reducing public funding for others. This move was generally welcomed by the Ivy League until Trump took on Harvard.

With such ominous trends on the horizon, brace yourselves for an implosion of the global education sector by 2030 – a reckoning mirroring the 2008 financial crisis, but with far graver consequences. And touching on the 2008 crisis, didn’t someone remark that “behind every financial disaster, there’s a Harvard economist?”

Nobody seems to be learning from previous contretemps. In fact, I dare say that ‘learning’ is merely a coincidental output of the Ivy League brand.

The credentialism trapWhen Lehman Brothers and its lesser peers collapsed in 2008, many Singapore-based corporations eagerly scooped up their laid-off executives. The logic? Fail upward.

If these whizz kids were truly talented, why did they miss the glaring warning signs during the lead up to the greatest economic meltdown since the Great Depression? The answer lies in the cult of credentialism and an entrenched patronage system. Ivy League MBAs and Rolodexes of central banker contacts are all that matters. The consequences are simply disastrous: A runaway global talent shortage will hit $8.452 trillion in unrealized annual revenues by 2030, more than the projected GDP of India for the same year.

Ivy League MBAs often justify their relevance by overcomplicating simple objectives into tedious bureaucratic grinds – all in the name of efficiency, smart systems, and ever-evolving ‘best practices’. The result? Doctors now spend more time on paperwork than treating patients, while teachers are buried under layers of administrative work.

Ultimately, Ivy League technocrats often function as a vast bureaucratic parasite, siphoning public and private wealth into elite hands. What kind of universal socioeconomic model are these institutions bequeathing to the world? I can only think of one historical analogue as a future cue: Colonial India, aka the British Raj. This may be a stretch, but bear with me.

Lessons from the Raj

As Norman Davies pointed out, the Austro-Hungarians had more bureaucrats managing Prague than the British needed to run all of colonial India – a subcontinent that included modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. In fact, it took only 1,500-odd white Indian Civil Service (ICS) officials to govern colonial India until WWI.

That is quite staggering to comprehend, unless one grasps how the British and Indian societies are organized along rigid class (and caste) lines. When two corrupt feudal systems mate, their offspring becomes a blueprint for dystopia.

India never recovered from this neo-feudal arrangement. If the reader thinks I am exaggerating, let’s compare the conditions in the British Raj and China from 1850 to 1976 (when the Cultural Revolution officially ended). During this period, China endured numerous societal setbacks – including rebellions, famines, epidemics, lawlessness, and a world war – which collectively resulted in the deaths of nearly 150 million Chinese. The Taiping Rebellion alone – the most destructive civil war in history – resulted in 20 to 30 million dead, representing 5-10% of China’s population at the time.

A broad comparison with India during the same period reveals a death toll of 50-70 million, mainly from epidemics and famines. Furthermore, unlike colonial India, many parts of China also lacked central governance.

Indian nationalists are quick to blame a variety of bogeymen for their society’s lingering failings. Nevertheless, they should ask themselves why US Big Tech-owned news platforms, led by upper-caste Hindu CEOs, no less, showed a decidedly pro-Islamabad bias during the recent Indo-Pakistani military standoff. Maybe, these CEOs are supine apparatchiks, much like their predecessors during the British Raj? Have they been good stewards of the public domain (i.e. internet)? Have they promoted meritocracy in foreign lands? (You can read some stark examples here, here and here).

These Indian Big Tech bros, however, showed a lot of vigor and initiative during the Covid-19 pandemic, forcing their employees to take the vaccine or face the pink slip. They led the charge behind the Global Task Force on Pandemic Response, which included an “unprecedented corporate sector initiative to help India successfully fight COVID-19.” Just check out the credentials of the ‘experts’ involved here. Shouldn’t this task be left to accomplished Indian virologists and medical experts?

A tiny few, in the service of a hegemon, can control the fate of billions. India’s income inequality is now worse than it was under British rule.

A way out?As global university inequalities widen further, it is perhaps time to rethink novel approaches to level the education field as many brick and mortar institutions may simply fold during the volatile 2025-30 period.

I am optimistic that the use of AI in education will be a great equalizer, but I also fear that Big Tech will force governments into using its proprietary EdTech solutions that are already showing signs of runaway AI hallucinations – simply because the bold new world is all about control and power, not empowerment. Much like the British Raj, I would say.

https://www.rt.com/news/618349-elite-universities-corrupt-empire/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 31 May 2025 - 5:37am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

russophobic....

A Czech court has handed a former teacher a seven-month suspended sentence for expressing pro-Russian views during a school lesson, local media reported on Thursday.

Martina Bednarova was also banned from teaching for three years and ordered to complete a media literacy course, according to the Ceska Justice news portal. The court reportedly said Bednarova misused her role by presenting “misleading information” to students.

The incident occurred in April 2022, shortly after the escalation of the Ukraine conflict, during a Czech language lesson at an elementary school in Prague. According to media reports, Bednarova described Russia’s military action of Ukraine as a “justified way of resolving the situation” and cast doubt on Czech television’s coverage.

She also said “Nazi Ukrainian groups” had been killing Russians since 2014, apparently referring to Ukrainian nationalist battalions such as Azov, which Moscow has accused of committing atrocities against ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine, and which the Kiev authorities dispute. Students recorded the class and alerted school officials, leading to Bednarova’s dismissal.

Judge Eliska Matyasova claimed Bednarova was not simply expressing personal views but delivering false information in a classroom where students could not question it. Bednarova said her remarks were part of a media literacy lesson and called the case politically driven. The verdict is not final, as she has the right to appeal.

The District Court initially acquitted Bednarova twice, with an appeals chamber backing the second ruling on free speech grounds. In January, however, the Supreme Court overturned the decisions and ordered a new review to assess whether her actions met the criteria for a criminal offense.

Prague has taken a strongly anti-Russian stance in recent years, especially in response to the Ukraine conflict, becoming one of Kiev’s staunchest supporters.

In its 2023 human rights report, the Russian Foreign Ministry labeled the Czech government’s actions as “Russophobic” and expressed concern over freedom of speech in the country.

It also raised concerns over the functioning of media in the Czech Republic and noted what it called a steady drift toward anti-Russian sentiment.

Russian will also be phased out as a second language by 2034 under new Czech education reforms, with students limited to German, French or Spanish. As of late 2023, over 40,000 Russian nationals lived in the country, making them the fourth-largest foreign community.

The Czech Republic, once part of communist Czechoslovakia and a Soviet-aligned Eastern Bloc member, became independent in 1993 after the 1989 Velvet Revolution and the Soviet Union’s collapse. Since then, the country has removed or altered hundreds of Soviet-era monuments, with another wave of removals following the 2014 Western-backed coup in Kiev and the escalation of the Ukraine conflict.

https://www.rt.com/news/618355-teacher-sentenced-prague/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

it altered the course of humanity....

Professor Brian Schmidt

Brian Schmidt and Ricard Holden addressed the National Press Club jointly this week. The following are full transcripts of the speeches.

Let me take you back to February 1940 to the University of Birmingham. World War II had just broken out, and 38-year-old Marc Oliphant, an Australian-born physicist, who went on later in life to found the ANU Physics department and the Australian Academy of Science, had just had his lab invent the modern microwave resonant cavity, that could create incredibly intense radio-waves in a device of a size such that you could hold it in your hands.

This was a discovery that revolutionised radar – allowing it to be ubiquitous, giving it great precision, and even enabling it to be put onto planes. Oliphant took the invention to the US for mass production. It has been argued that more than any other single thing, this physicist’s invention altered the course of the war in the Allies’ favour, profoundly diminishing the effectiveness of the German Luftwaffe.

But that is not all that happened that February. Two Jewish physicists, who had fled Nazi controlled Europe, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, had taken up positions in Oliphant’s Lab and were tasked by Oliphant to work on nuclear fission – because the radar work was too top-secret for German nationals to work on. While he focused on radar, Oliphant asked them to calculate how much of the newly discovered element Uranium235 would be required to create a nuclear chain-reaction. The answer they came back with a few weeks later was startling, about 5kgs, and has altered the course of humanity. They had demonstrated that a nuclear bomb was possible – and given the advanced state of physics in Germany at the time, it seemed inevitable the Germans would create one. Oliphant ventured, as with radar, back to the US, this time with the nuclear secret, and thus was born the Manhattan project.

Germany arguably had the most advanced physics research capability in the world in the 1920s and early 1930s – but by 1940, they didn’t. The Nazis drove away all of their Jewish scientists – which were a large fraction of the German scientific endeavour, and treated the scientists who remained largely with contempt as dangerous intellectuals. The refugee scientists took up residence largely in the UK and US, creating a technical ascendency for the allies — whether it be in radar, bomb sites, penicillin, code-breaking or nuclear weapons — and was a major part of the ultimate defeat of the Nazi regime.

We are now seeing how quickly the nature of conflict has evolved in the Russia-Ukraine war, and we can expect new technologies based around small-scale automated machines, hypersonic missiles, and computer warfare to feature prominently if we are to have future conflicts between advanced economies. In such a case, the research capability of a country will be incredibly important at influencing the overall winners and losers, because once the conflict starts — you have what you got — you do not suddenly create the research and researchers – that takes decades. I hope we never get to this state. But nor should we stick our heads in the sand and ignore the possibility.

The much better part of research, however, is the prosperity it brings, through new products and ideas that make lives better. But understanding the research ecosystem remains elusive for much of the public, politicians and even policymakers.

One of the most common conversations I have with people, especially politicians, goes something like this. “Hey, Professor Schmidt, the astronomy you do is really cool – but why does the government pay you to do it?”

It’s a question that ruffles many of my colleagues’ feathers.

“The Universe is beautiful. Understanding it has deep cultural significance. It fills the world’s heart with wonder” …

And indeed those are reasons why I chose to study astronomy when I was 18. But these really are not the reasons why the government funds my research.

The government funds the study of the Universe, ultimately, because the knowledge we create and the people we train create immense value for Australia, and for the world.

Just look to your iPhone as an example. My areas of astro-particle physics provided the breakthroughs necessary to enable

Our graduates, while many work as academics, even more work in high-tech companies, defence, government and finance. As Richard will soon talk about, their ideas boost productivity.

But as a minister once asked me, “Yeah, but Brian, why do we have to do the astronomy… can’t we just go straight to the good stuff?” It sounds perfectly sensible, but it doesn’t seem to work in practice. The exciting part of innovation is not incremental, it is revolutionary. Yes, we need entrepreneurs to take new ideas and work on the “good stuff”, but we also need to have a sea of ideas that is continuously replenished from which innovators can fish for the next big thing. As Richard will explain, this public-good basic research is a classic market failure, and a place where governments need to intervene.

Let me tell you how it works for me personally. I immigrated to Australia in 1994 because Australia had invested for 50 years in astronomy, and I knew I could competitively do my project to measure the fate of the Universe, based here in Australia at the ANU. It was an environment every bit as good as what I had at Harvard. That basic research program, in addition to winning me a Nobel Prize, put me in close connection with world-leading instrument groups, with national and world leaders, with tech giants, and financiers.

It positioned me to lead the national university for eight years, where we radically overhauled our technology transfer program to emphasise getting our ideas out of the university so Australian society could benefit, and not spend our time killing ideas through a fixation of ensuring future royalty streams would come to the university. This change increased the deals flowing out of the university by an order of magnitude, including two companies that are based on the efforts that went into the Nobel prize=winning detection of gravitational waves from merging black holes (in which I also played a small role).

One of those companies is Liquid Instruments (whose founder Daniel Shaddock is here in the audience today) which is revolutionising measurement and test equipment by replacing the usual intricate array of custom hardware components with software and high-speed computation. It is now manufacturing its products here in Australia, with millions of dollars of sales globally, and is on a path to become a major global tech-firm. When I was asked by the Liquid Instruments Board recently to join them, I knew I had experience that could help them become an iconic global tech-firm, but also had a responsibility to Australia to help make it happen.

So, when astronomers ask the nation to continue to support our world-leading research through investment in the next generation of facilities — and, yes, we know it’s expensive — remember that we provide great value to the nation through a range of spillovers that include some of the most significant Australian innovations, but a range of less direct things with respect to skills, capability, relationships, and public engagement that comes from our global excellence. Our past has demonstrated that public investment was actually useful, and we have plans to be even more useful into the future.

A challenge we have, though, is that the dividends such research pays are measured in decades, not in the time-scale of elections. The public, and the politicians they elect, are impatient, and are prone to create a set of new programs that seem OK, but fail to create the long-term ecosystem from basic research to R&D-intensive companies that Australia needs to boost our productivity.

So rather than just admire the problem, let me outline what I think success might look like.

The first thing is continuity. Research works on decadal-long horizons, and when we improve our sovereign research system, we need to think in those time-frames, not in terms of one-off programs.

In the 13.5 years since I was awarded the Nobel Prize, I have had the privilege to work with 16 different science ministers. The longest serving of those, Ed Husic, is here today, and I want to thank him for his efforts. I am sure that he will continue to help the Parliament shape the innovation ecosystem into the future. To his successor, Tim Ayres, I look forward to working with you, and a genuine ask is for you to serve as minister for at least as long as Ed did. We will not improve our system without continuity.

Secondly, we need to positively engage in creating a comprehensive program across the ecosystem, not a series of one-off policy announcements that last 12 months and leave gaping holes.

I say positively for a reason. For the past two years, as a nation we have spent a great deal of time talking about what we do not like about our universities. I, at least, have heard the message loud and clear. But it is time to focus on what we want out of these institutions as a nation, especially with respect to our sovereign research capability. And this extends to agencies like CSIRO and ANSTO as well.

Right now, Australia’s policy environment does not obviously support our aspirations. For example, AUKUS is not just nuclear subs, but it is also meant to be a comprehensive technology partnership to create advanced capabilities in a range of disciplines that concentrate around the physical sciences and engineering. Similarly, our critical minerals strategy requires a range of expertise cutting across geology, geo-chemistry, and engineering.

As someone who recently finished leading a university that worked in all of these disciplines, let me tell you that current policy environment is forcing universities to divest and do less in these areas, not more. Infrastructure and equipment, materials, and buildings of these subjects are the most expensive of any research areas, and are not paid for by the Commonwealth. The jobs-ready graduate program reduced substantially the resources universities get per student in these areas – if you want a program that creates world-class graduates in these areas of national interest, it’s going to run at a loss. Richard will talk more about this problem.

Finally, we need to spend a lot of time and effort creating R&D intensive companies. This could be new companies, like Liquid Instruments, or it could be getting the right local companies to be prepared to use R&D to grow through innovation – and this usually means thinking globally, rather than concentrating on our domestic market.

Understanding the market failure that is occurring in our innovation ecosystem is a major piece of work, worthy of our best minds, and a long-term comprehensive response is warranted. I do not have a complete set of answers, but I do note that some recent policy interventions have been good, like the recent PhD internship program, which encourages PhD students to spend time in Australian companies. It is good for the students, and with low friction is bringing researchers and companies together more effectively than anything else I have seen. And it’s pretty cheap.

Something that is not cheap is the continually evolving R&D Tax concession, which has not proven to be the panacea which one might hope, given it costs taxpayers each year more than the research funding contained in the ARC, the NHMRC, CSIRO, Defence Science Technology Group, and Medical Research Future Fund combined. It is not that I do not think such expenditure might be warranted, but one should expect results from this level of investment that are not obviously present.

Members of the business community here will be rolling their eyes. “Not another change to the R&D Tax concession!” So while I have earlier emphasised the importance of continuity, I am also reminded of the apocryphal quote (and no, Einstein did not say this) that “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results".

We need to take a big look at the ecosystem, like Robin Batterham did in 2001 with the five-year Backing Australia’s Ability Program. It didn’t get everything right (it is where the R&D Tax concession came from), but it thought through the ecosystem, and made a comprehensive set of policies. What we have failed to do since, is a holistic five-yearly refresh of that program, where we learn what has worked, and discard what hasn’t – it really has been a year-to-year series of wall-paper jobs for the last 20-odd years.

I hope that I have reminded you that our sovereign research capability has enormous consequences for Australia’s future. I would hope that we would never forget this, but I look around and I am scared. The Australian Government investment in its sovereign research capability was one third higher 15 years ago as a fraction of GDP, and in the United States, our largest research partner, the university sector is under siege on multiple fronts, including the Trump administration proposing to immediately halve expenditure in the NSF and NIH – the bedrocks of US research.

Let me remind you what China is up to – they have raised their R&D spend by 8.3% last year, having increased their R&D spend as a function of GDP by more than a factor of five in the time I have lived in Australia. During that same time, Chinese GDP has grown in real dollars by more than a factor of 20 – the two figures are not unrelated! That’s a 100-fold increase, of which many of the benefits to the Chinese nation have yet to accrue.

As I finish and hand over to Richard, I want you to think what their increase and our decrease means for Australia’s future economic and security environment. I find it a sobering thought.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/05/brian-schmidt-on-securing-australias-sovereign-research-capability/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

securing....

Richard Holden

Richard Holden on securing Australia’s sovereign research capabilityRicard Holden and Brian Schmidt addressed the National Press Club jointly this week. The following are full transcripts of the speeches.

The Economic Value of Ideas

Beginning in the 1990s, economists developed a framework for articulating the economic value of ideas.

Paul Romer was at the forefront of this and was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his contribution. This area of economics has become known as endogenous growth theory. Rather than taking the rate of technical progress as being given, or exogenous (as the then standard “neoclassical” model of economic growth did), Romer emphasised that the rate of technological progress is determined by the generation of ideas and scientific knowledge.

His key observation was that knowledge can be an important driver of long-run economic growth in a market economy. Before Romer, economists thought of economic growth as being determined solely by physical capital and labour. Romer expanded this to include knowledge and noted that the stock of knowledge is determined by research and development activities broadly conceived. This includes what universities refer to as both basic research and also applied research.

There are two things about “ideas” that are different from physical capital (like machines). First, they’re “non rival.” If one person is using Pythagoras’s Theorem, it doesn’t prevent anyone else from using it. In other words, once discovered, there’s no monopoly on finding the length of the hypotenuse of a triangle. This is very different from standard economic goods. If one person is eating a salad, it precludes other people from eating that salad. Second, some ideas can be made “excludable” – in the sense that others can be prevented from using them through policies such as patents, or through technologies like encryption.

The production of ideas often involves large fixed-costs — such as the initial research and development — and low marginal costs for the subsequent production of each unit of the good or service. Economists refer to this as increasing returns to scale. Excludability, such as through patents, is important for allowing firms to recover their initial fixed costs. Otherwise, ideas may never be developed in the first place. Balancing non-rivalness and excludability has been a major focus of economists’ work on economic growth.

One important insight is that decentralised, market-based solutions will not always lead to the right balance of excludability and non-rivalness. This points to a role for different forms of knowledge production. Romer himself emphasised the importance of universities. Universities have long been, and continue to be, a major source of basic and applied research. This makes university research a fundamental driver of economic growth.

In fact, endogenous growth theory is essential in explaining some basic empirical facts about economic growth. These facts only started to emerge in the mid-1980s with the rise of large, cross-country datasets on growth over time. The neoclassical growth model could not explain persistent differences between countries in the rate of economic growth.

It also predicted that poorer countries would grow faster than richer countries because of decreasing returns to physical capital. This wasn’t true in the data either. Endogenous growth theory provides a compelling explanation of the essential empirical facts about economic growth. Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Lucas once observed that “once you start thinking about economic growth, it’s hard to think about anything else". Anyone who doubts that, would do well to compare and contrast the relative fortunes of Japan and the United States over the past three decades.

In 1995 Japan’s GDP per capita — a good measure of living standards — was US$44,000 per capita (in 2022 dollars). United States GDP per capita was just under US$29,000 in 1995. So Japan’s living standards were 54% higher than those in the United States. Fast forward to 2022 and the U.S. had grown to over $76,000 per capita. Japan, after a series of “lost decades”, had actually shrunk to $34,000 per capita – or 55% lower than the United States. The US had grown at 3.7% per annum while Japan had shrunk at 1% per annum.

So it’s not an overstatement to say that generating and applying knowledge is the cornerstone of rising living standards. Countries that consistently do it better can provide their citizens with more public goods like healthcare and high-quality education, more opportunities for social mobility, and better lives.

We are, thankfully, speaking more and more about productivity in Australia. This is where productivity comes from.

Funding Australia’s sovereign research capability

So how do we go about funding sovereign research capability in Australia?

Start with this.

We’ve become addicted to funding that research capability through international student income. In a time of global uncertainty and upheaval, this is a huge strategic risk. It places a ticking time bomb beneath Australia’s security and prosperity.

International student income pays for much of our research infrastructure. It pays for buildings, electricity, scientific equipment and a range of other overheads necessary to undertake scientific research that is partly funded by government.

Commonwealth grants provide an overhead rate of less than 20%. By contrast, in the cradle of innovation — the United States (pre-Trump 47, and I’ll come back to that) — universities typically get the true cost of about 55%. So every time an Australian university gets a grant, it has to find an additional 35% just to keep the lab’s lights on.

Actually, it’s worse than that. Our universities need to demonstrate “skin in the game” to win those grants. This involves everything from salary support for young scholars to comply with enterprise bargaining agreements, to matching money for the grant.

In the flagship ARC Centres of Excellence program — which has been behind Australia’s much-lauded quantum capability and its numerous high-tech spinouts — universities need to match government funding dollar-for-dollar.

The fields that are the most expensive require universities to stump up the most money. What are those fields, you may ask? Well, just look at the AUKUS Pillar 2 list.

Right now, the Department of Education funds overheads from a common pool — one that hasn’t been growing in real terms — not just for the research grants it manages, but for an ever-increasing list of research funding from philanthropy, business, state governments and other agencies. As more things get added to the pool, the overhead rate drops for everything, including the Commonwealth’s grants.

This is the very definition of a broken system.

A better approach would be for each funder to cover the overheads associated with their own research program. Education would be responsible for the ARC and the other programs it administers.

If other agencies, like Defence want to increase their research, they’d need to also find money for overheads, rather than drawing on the common pool. State governments, business, philanthropy and the Medical Research Future Fund would have responsibility to fund their own research agendas, and not rely on the Commonwealth to subsidise their overheads.

This would cost $1.2 billion a year.

The hard truth is that we’ve had 15 years of bipartisan disinvestment in research expenditure. Relative to GDP, Australian R&D spending was one third higher when Kevin Rudd was Prime Minister than in 2023. Over these 15 years business expenditure is down, and government expenditure is down. Only university expenditure on R&D has risen. And that increase has almost entirely been funded by foreign student fees.

Sovereign research capacity is built over decades, but can be lost in months. We must stop dithering.

Now I can stand here with a straight face and say that $1.2 billion a year in the context of a $700 billion federal budget and a nearly $3 trillion economy is, to be blunt, a rounding error.

But I’m also conscious that sounds an awful lot like I’m talking my own book. And I’m acutely aware that some of my friends in the university sector have stood at this very podium, told stories about what’s good about research, and asked for a blank cheque.

That’s ok. That’s their job.

But I’m here to do something different.

I want to emphasise that, yes, that $1.2 billion will earn a very high social and economic return for Australia. And in a tumultuous global landscape, where we can no longer rely on our most important ally the way we have in the past, we must secure our sovereign research capability. It’s essential for our economic and national security.

But funding research the right way, will also align the incentives of the sector much more closely with the goals of government and the desires of the Australian people.

As anyone in corporate life knows, cross subsidies are poison. Cross subsidies muddy the price signals that best guide resource allocation decisions. They produce a lack of transparency. And they create significant incentive problems.

In this instance, what is true in corporate life is also true in university life.

And right now, we use international student revenues to cross-subsidise research.

That doesn’t mean that international students aren’t incredibly valuable for Australian universities and for Australia. They are.

They help fund better instructors and more resources for teaching domestic Australian undergraduate students in an increasingly competitive and globalised tertiary-education landscape. They allow Australian undergraduates to get what is often a genuinely world class education for one-fifth of what it costs at comparable universities in the United States. They provide significant financial benefits across the economy – far beyond our university campuses.

But when we have a huge misalignment between the source of revenues and the use of revenues, well, we’re just asking for trouble. And trouble is what we’ve seen.

Funding research properly is not so much about “more money”. It’s about “the right money”. By better aligning the incentives of universities and the desires of the public, we can turn what has too often been zero-sum conflict into a mutually beneficial joint enterprise for the benefit of the nation.

The Trump challenge

Prime minister Jim Hacker once said: “May I remind the secretary of state for Defence that every problem is also an opportunity?” To which Sir Humphrey replied: “I think that the secretary of State for Defence fears that this may create some insoluble opportunities.”

What President Trump is doing to research funding in the United States is a bit like that.

Some of the world’s great universities are under direct attack. Harvard — the oldest university in the United States and the most important in the world — just had US$2.2 billion in funding stripped for having the temerity to resist the Trump administration’s push to intervene in their choices of faculty, students, and their curriculum. Now they’ve been banned from enrolling international students, including Australians.

The overheads on NIH grants have been slashed. And the government is simply refusing to reimburse expenditures on existing grants from the National Science Foundation and other sources.

I just came back from a week at MIT and Harvard and I heard directly the concerns faculty members have over what will happen to students, researchers and the pathbreaking research these institutions undertake.

Australia is not immune from the carnage in US higher education. The Australian Academy of Science estimates that more than $300 million of funding for research by Australian university researchers is already in jeopardy. This has serious implications not only for the research involved, but for Australian researchers – especially those at earlier stages of their careers. It will damage — perhaps shatter — longstanding and valuable collaborations between Australian and US researchers.

We will need to plug this gap. This is the “problem” part of the equation. But there’s also the “opportunity” part.

With the US stepping back from its leadership role, Australia has a chance to step up. In coming months and years, many leading US researchers may be looking to move their labs, their families and their lives abroad.

If we act decisively, Australia can be as, or more, attractive a destination for those researchers as Europe which — if we’re being honest, and there’s no reason not to be — has its own issues.

What’s happening to US research and researchers is shocking. But this act of American self-harm is our opportunity. And it’s an opportunity that has never arisen before and may never arise again.

In justifying his acceptance of a US$400 million aircraft from Qatar, President Trump invoked the words of legendary golfer Sam Snead: “When your opponent gives you a putt, just say thank you and walk to the next tee.” Now it turns out Sam Snead never actually said that, but that’s not important right now.

In destroying the US research ecosystem, President Trump is giving us a putt. A freebie. We should say “thank you” and walk to the next tee. Along with some of the world’s finest researchers.

A Future Made in Australia

The Albanese Government speaks of “a future made in Australia”. The prime minister seems to have in mind the manufacture of physical goods. I’ve made no secret of my scepticism about our ability to turn the clock back to the 1960s.

We have a better chance when it comes to advanced manufacturing – as I wrote about in my 2022 book From Free to Fair Markets with Rosalind Dixon. Germany has a long history and proud tradition in this area. But other leading countries in high-tech, high-wage, advanced manufacturing of precision goods include France, Italy, and the Netherlands. Surely Australia can compete with those countries?

But let’s not forget that “ideas” are things, too. They need to be produced as well. And, as I emphasised earlier, ideas are a crucial driver of economic growth and living standards.

A Future Made in Australia can, and should, be one where we manufacture ideas not just physical goods.

We live in a rapidly changing world. A world whose technological possibilities, economies, and social interactions will be determined by the ideas that we create and implement.

Evolutionary biologists have a concept called “punctuated equilibria” where evolution of a species can proceed in a leap, rather than gradually. And legal scholar Bruce Akerman has spoken of “constitutional moments” where there can be great change to constitutional arrangements in a short period of time.

We are living through a “technological moment.” We don’t know what this moment will bring. We don’t know all the challenges that will arise, or opportunities that will unfold. We don’t know what it will mean for Australia and our place in the world.

This might seem daunting, even scary.

But we should reflect on, and be comforted by, the words of Robert F. Kennedy in 1966: “Our future may lie beyond our vision, but it is not completely beyond our control.

”We have a choice. We can meet this technological moment, or miss it. We can embrace this moment, or evade it. We can secure our research sovereignty, or surrender it.

I hope we’ll do the former.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/05/richard-holden-on-securing-australias-sovereign-research-capability/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

DEI.....

DEI Should Have Ended Harvard’s ‘Elite’ Status 60 Years Ago (Or More) BY: JOY PULLMANNStrong evidence contradicting Harvard University’s claim of elite status was available decades before the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University lawsuit the Supreme Court ended in 2023. Harvard’s subjugation of merit to politics goes all the way back to at least the 1920s, when, as Justice Clarence Thomas noted in his SFFA v. Harvard concurrence, it set quotas on Jews to reduce their enrollment.

Indeed, as I note in my recent book about identity politics, “the federal government had begun hiring people based on race” and demanded the same of its contractors as far back as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency in the 1930s and 1940s. Under Roosevelt, the federal government pioneered the “disparate impact” doctrine today better known as diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act and other identity politics measures of the era were immediately interpreted by federal agencies and courts as requiring employers such as universities, even private ones, to hire and promote on the basis of sex and race. So, as I explain in False Flag, even though the Civil Rights Act explicitly bans “preferential treatment” by race or sex, it has always been used by federal agencies and courts to require the opposite.

This means, as Thomas testified in the 2020 documentary Created Equal, racial discrimination in favor of minorities at so-called elite schools was already widespread when he studied law in the early 1970s. Thomas was accepted to Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale law schools, and went to Yale.

Ivy League DEI Since At Least the 1970sIn Created Equal, Thomas says he struggled to find a job after law school because 1970s law firms knew black Ivy League graduates had been admitted with significantly lower qualifications than white graduates. As Thomas writes in his SFFA v. Harvard concurrence, “I have long believed that large racial preferences in college admissions ‘stamp [blacks and Hispanics] with a badge of inferiority.’”

Thomas, of course, is the most brilliant American legal mind of his lifetime, a peerless justice who sets the standard of constitutional analysis. Anyone who reads his work can see he didn’t need affirmative action.

Its use, however, harmed him and everyone else it claimed to “help.” In his memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, Thomas writes that while struggling to find a job he bitterly affixed a 15-cent price sticker to the frame of his law degree “to remind myself of the mistake I’d made by going to Yale. I never did change my mind about its value.”

In the 1980s, it remained well-known in posh circles that being Asian or white reduced one’s chances of Ivy League admission. By the 1990s, Charles Murray and Richard Hernnstein quantified the boost that being black or Hispanic gave Ivy League applicants as around 200 to 300 SAT points, depending on the school — an enormous difference in academic ability akin to men’s natural advantages over women in sports. The prevalence of racial discrimination in university admissions from the 1960s on, especially at allegedly top-tier schools, led to 1990s policies such as California’s affirmative action ban in 1996.

But for half a century, universities have largely ignored such restraints and kept on discriminating. The SFFA vs. Harvard lawsuit only confirmed Harvard had continued its 60-year practice of admitting black and Hispanic students with much lower academic records than those of admitted Asian and white students. And it is still engaging in high-dollar litigation to protect its half-century record of excellence-destroying racial discrimination.

Racial Discrimination Destroys ExcellenceThis means that for at least 60 years universities that claim to be elite have prioritized politics over excellence. This also affects teaching quality, and may help explain why research suggests teaching quality at “elite” colleges is no better than at lower-ranked colleges.

While the students whom race preferences mismatch to universities drop out more and earn lower grades than students who are truly elite academically, many remain through graduation. This pushes professors to accommodate them in lectures, assignments, and grades. It is probably a contributing factor in the rampant grade inflation at Ivies that makes four out of every five grades at Harvard and Yale an A, itself a marker of less-than-excellent academic quality.

It also leads to periodic scandals when professors are caught noticing this reality. University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax was suspended for a year at half-pay, and her university attempted to strip her tenure for anti-affirmative action statements including, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a black student graduate in the top quarter of the class, and rarely, rarely, in the top half. I can think of one or two students who scored in the top half of my required first-year course.”

In 2021, Georgetown Law School fired adjunct professors Sandra Sellers and David Batson for a private conversation in which Sellers told Batson, “I hate to say this. I end up having this, you know, angst, every semester that a lot of my lower ones [students] are blacks. Happens almost every semester. And it’s like oh, come on. You get some really good ones. But there are also usually some that are just plain at the bottom. It drives me crazy.” Batson responded with a neutral “Mmhmm.”

Georgetown and U-Penn are supposed to be top-tier law schools. But no university that engages in such pervasive academic fraud can be considered elite. And racial discrimination is not the only mark against Ivy League and other “top-tier” schools’ PR claims. It is just the sharp point of a large iceberg of intellectual corruption.

Decades of Expensive and Useless ‘Research’Cultural Marxism doesn’t just ruin classroom and graduate quality, but also universities’ other main product, research. “Top-tier” universities are the top contributors to the replication crisis not just in the almost wholly corrupt humanities but also the allegedly “hard” sciences. In short, the replication crisis means that most of the scientific work that boosts the reputations of so-called “top-tier” universities is fraudulent. Donors and taxpayers have paid billions of dollars to attain nothing except self-deception.

Could it be that systematically elevating students, staff, and faculty for more than half a century on the basis of race, sex, and political affiliation instead of intellectual capabilities has contributed to the complete unreliability of universities’ work? It certainly stands to reason, especially when combined with continuing revelations of Ivy professors’ and presidents’ plagiarism.

Data SFFH v. Harvard unearthed showed the majority of Harvard’s students would not be enrolled without some preference. Admissions preferences include athletes (who on average exhibit the lowest academic records of all students admitted) and children of alumni, donors, celebrities, and staff. These comprise 29 percent of admissions. Add to that Harvard’s 27 percent of international students (some of whom will overlap with the donor preference), and the race preferences for black and Hispanic students, and you have a clear majority of students admitted due to some preference that has nothing to do with merit.

Highly Credentialed IncompetenceThis suggests the minority of students who did earn their way into Ivies provide intellectual window-dressing for the rest. It also indicates Ivy League experiences are today elite in perhaps only one sense: access to power. Thus Harvard lends its prestige to leftist incompetents such as Joy Reid and Bill De Blasio. (Next it will be Gavin Newsom.)

Rent-seeking can and nowadays most often does pay better than hard work and individual excellence. But that system cannot be called a meritocracy, and its gatekeepers cannot be called “elite” at anything but deception.

Joy Pullmann is executive editor of The Federalist. Her latest book with Regnery is "False Flag: Why Queer Politics Mean the End of America." A happy wife and the mother of six children, her ebooks include "Classic Books For Young Children," and "101 Strategies For Living Well Amid Inflation." An 18-year education and politics reporter, Joy has testified before nearly two dozen legislatures on education policy and appeared on major media including Tucker Carlson, CNN, Fox News, OANN, NewsMax, Ben Shapiro, and Dennis Prager. Joy is a grateful graduate of the Hillsdale College honors and journalism programs who identifies as native American and gender natural. Joy is also the cofounder of a high-performing Christian classical school and the author and coauthor of classical curricula. Her traditionally published books also include "The Education Invasion: How Common Core Fights Parents for Control of American Kids," from Encounter Books.https://thefederalist.com/2025/06/04/dei-should-have-ended-harvards-elite-status-60-years-ago-or-more/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.