Search

Recent comments

- success....

3 hours 33 min ago - seriously....

6 hours 17 min ago - monsters.....

6 hours 25 min ago - people for the people....

7 hours 1 min ago - abusing kids.....

8 hours 34 min ago - brainwashed tim....

12 hours 54 min ago - embezzlers.....

13 hours 34 sec ago - epstein connect....

13 hours 12 min ago - 腐敗....

13 hours 31 min ago - multicultural....

13 hours 37 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

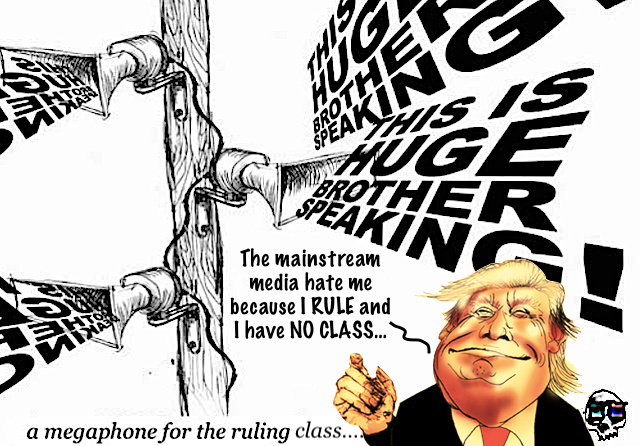

promoting our system of inverted totalitarianism....

The commercial or mainstream press is a megaphone for the ruling class. It genuflects before establishment politicians, generals, intelligence chiefs, corporate heads and hired apologists who carried out the corporate coup d’état that created our system of inverted totalitarianism.

Journalists and Their Shadows (w/ Patrick Lawrence) | The Chris Hedges Report

The corporate structures that have a stranglehold on the country and have overseen deindustrialization and the evisceration of democratic institutions, plunging over half the country into chronic poverty and misery, are in the eyes of legacy journalists unassailable.

They are portrayed as forces of progress. The criminals on Wall Street, including the heads of financial firms such as Goldman Sachs or for-profit health care corporations such as UnitedHealth, are treated with reverence. Free trade is equated with freedom. Deference is paid to democratic processes, liberties, electoral politics and rights enshrined in our Constitution, from due process to privacy, that no longer exist.

It is a vast game of deception under the cover of a vacuous morality. Those cast aside by corporate capitalism—Noam Chomsky calls them “unpeople”—are rendered invisible and reviled at the same time. The “experts” whose opinions are amplified on every issue, from economics to empire and politics, are drawn from corporate-funded think tanks, such as the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute, or are former military and intelligence officials or politicians who are responsible for the failure of our democracy and usually in the employ of corporations.

Cable news also has the incestuous habit of interviewing its own news celebrities. The most astute critics of empire, including Andrew Bacevich, are banished, as are critics of corporate power, including Ralph Nader and Chomsky. Those who decry the waste within the military, such as MIT Professor Emeritus Ted Postol, who exposed the useless $13 billion anti-ballistic missile program, are unheard.

Advocates of universal health care, such as Dr. Margaret Flowers, are locked out of national health care debates. There is a long list of the censored. The acceptable range of opinion is so narrow it is almost nonexistent.

How did this happen? How did the press turn itself into a fawning echo chamber for the billionaire class? What does this mean for our fading democracy? What can we do to fight back? Joining me to discuss the decrepit state of journalism is Patrick Lawrence who worked for many years overseas for the International Herald Tribune and Far Eastern Economic Review. He is the author of Journalists and Their Shadows.

You start the book, Patrick, with the Cold War. This was perhaps the training ground for the state that we’re in. You write, you’re talking about the major dailies and the networks,

“They delivered the Cold War to our doorsteps, to our car radios, into our living rooms. They defined a consciousness. They told Americans who they were and what made them American and altogether what made America America. A free press was fundamental to this self-image and Americans nursed a deep need to believe they had one. Our newspapers and networks went to elaborate lengths to give this appearance of freedom and independence. That this was a deception, that American media had surrendered themselves to the new national security state and its various Cold War crusades is now an open and shut matter of record. I count it among the bitterest truths of the last seventy five years of American history.”

You’ll actually go on in the book and argue that where we are now is worse but let’s begin there because I think it is an important kind of winnowing journalists like I.F. Stone, of course, are pushed out of even The Nation magazine wouldn’t publish Stone. The Nation magazine pushed you out I think over Ukraine right? Russiagate.

Patrick Lawrence

Russia, Russiagate.

Chris Hedges

The fantasy of Russiagate. But let’s begin with that, what happened to the press.

Patrick Lawrence

Well, first of all, thanks for having me. Delighted to see you again. One of the things I wanted to do with the book, one of three, is to give the present press mess, as I call it, a history. Most, I don’t know what percentage of your listeners lived through those years, the Cold War, part of it, all of it, none of it, but what’s going on now has a long history.

It goes back to the earliest days of the Cold War. And it is extraordinary the extent to which the mistakes and derelictions of that time are being repeated with just astonishing exactitude, the same things.

Why? Because the errors and corruptions of that time were never acknowledged. And if you don’t acknowledge your mistakes, you cannot learn from them. The press is not an institution fond of learning from its mistakes. So I wanted to give it a history, first of all.

I think it’s important if we’re going to understand where we are first and where we might go second, you need to know the past, right? That was my objective there.

Chris Hedges

Well, let’s just characterize it. First of all, I don’t think they were mistakes. The careerists within the press read the landscape very, very well. I once had dinner with the odious Joseph Alsop, who proceeded to get drunker and drunker. And I was a young graduate student, I was a seminary student and turned on me in this company and railed on my generation who didn’t know the Bible or Shakespeare, both of which I knew far better than Joseph Alsop.

I read the Bible in Greek. But let’s talk a little bit about, you developed a class of journalists who catered to what C. Wright Mills called the power elite during the Cold War. Many of them, as you point out in the book, were recruited by the CIA or at least served as useful idiots for the CIA in terms of feeding information. And this was very common in the Cold War.

If you signed on for that quote unquote crusade for patriotism against communism, you did very, very well. And you’ve worked at the International Herald Tribune, I worked at the New York Times. We’re talking about consummate careerists. So what you call, we’re the mistakes. We’re the ones who actually thought journalism was about integrity and we got pushed out. So let’s be clear about that. These people didn’t make a mistake. They made very astute career choices.

Patrick Lawrence

Let me change, I stand corrected, let me change the word, not mistakes, transgressions. Can we live with that?

Chris Hedges

Alright.

Patrick Lawrence

Transgressions of principle. Yeah. Where to begin? There are a few ways to discuss this. One is the professionalization of the craft. There are two ways to use that term. One is to learn your trade, learn your techniques and all that. You’re a professional in your procedures. I quite value that.

The way I mean it in the book is professionalization as it began in the 1920s when journalists began to identify themselves not as residents of an independent pole of power reporting on the institutions they would be charged with observing, but as part of the power structure, a disastrous drift in the profession.

It goes back to Walter Lippmann in the 20s. He wrote three books about the press. In a certain way, that’s what they were about. So the professionalization.

Chris Hedges

Well, let’s stop with Lippmann because Lippmann is an extremely important figure because his thesis is that the general public is just too clueless to understand how to manage ruling institutions and therefore he argues, in essence, that they should be kept in ignorance, manipulated, used, and that should be left up to what you call the quote unquote professional class, including this new professional class, the press.

And as you point out in the book, before all this, journalists were working class stiffs who didn’t go to college. And that, I mean, you could hold a sizable reunion for any Ivy League school now in the newsroom of the New York Times, or at least when I was there.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, I mean, [H. L.] Mencken is great on that. You know, I quote him saying, you know, in the old days, a reporter made the same salary as a bartender or a police sergeant. Now he’s making what a doctor or a lawyer makes.

He noted that with some regret. Now, with Lippmann, I mentioned later in the book what are known as the Lippmann-Dewey debates in the 1920s. In fact, there were never any formal debates, but they exchanged by way of their books and reviews of their books. Lippmann considered, as you say very well, these two were formulating these ideas as America was becoming a mass society. That’s the background.

And Lippmann considered people are simply incapable of understanding the world around them. They have to be told what’s going on. They’re too busy. They’re too distant from power. So the function of the journalist is, as a messenger, if you will, sort of a tribune, part of the power elite. Bearing the policies and judgments and directives of the powerful, the political structure downward to the population. That was his notion of what the press was supposed to do.

Along came [John] Dewey. I’m not a great Dewey man, but I think he was correct in this, right? He said, no, the journalist has to stand, as I put it, has to stand in a different place. He has to stand outside of power and present to readers and viewers the known considerations whenever a question of national policy was at issue, and engender a public debate so people could draw their conclusions and register those conclusions.

That was the function of the journalist, right? Again, I have a lot of problems with Dewey. That’s a separate conversation. But on this point, where the journalist was located, he was right, right? Now, what do we have now? We have an emphatically Lippmannite press corps, right? These people don’t, so far as I can make out, are completely happy that this is understood as we’re talking about it.

We are part of the power structure and we are handing down to you what’s going to happen, supposedly why, although that’s never very clear, and how you should think. Remember, it was Lippmann who gave us the manufacture of consent. That was in one of the three books he wrote in the 20s, the period I’m talking about.

Chris Hedges

Let’s talk about what happened. You write that everything began to close after the 1975 defeats in Southeast Asia wounded the American psyche and rattled the power elite. Then it disappeared more or less completely as the Cold War years gave way to the post-Cold War triumphalism that marked the 1990s.

There followed the events of 2001, these were the 9/11 attacks. These proved a decisive moment in our media’s return to the worst of many bad habits they had formed during the 1950s. So you mark that notion of a unipolar world with the collapse of the Soviet Union. I was in Eastern and Central Europe then and watched it.

But then you also mark 9/11 when the country, after these attacks, drank that very dark elixir of nationalism. And the flip side of nationalism, of course, is racism. And began these military debacles that continue to this day in Ukraine and Gaza and everywhere else. But talk about those historical moments.

Patrick Lawrence

Okay, remember beginning the afternoon of September 11th and running for some days afterward, the constant repetition of the planes colliding with the towers, I’m sure everyone listening will recall that. My view is that that was what the literary critics call an objective correlative, okay? That moment was really most profoundly understood, most profoundly as a matter of psychology.

Americans until that moment were taught from [John] Winthrop onward that we are immune from history, right? As [Arnold J.] Toynbee once said, history is what happens to other people. At that moment, that mythology came to an end. Suddenly, we are as vulnerable to time and history as the rest of the world. It was a profound shock.

And I think at the level of the imperium, the policy cliques began to understand the world had profoundly changed. And at that point, the press needed to be… so it was, a new set of circumstances, well, new, with a history, a new set of circumstances and the press had to be recruited. There’s a passage in the book recounting what happened a few days after 9/11. Bush’s press secretary, forgive me, I forget his name.

Chris Hedges

Ari Fleischer.

Patrick Lawrence

Ari Fleischer called in all the heavyweights in the Washington press corps, the senior editors mostly, perhaps a correspondent here or there, maybe Tom Friedman, people like that, and said, look, we don’t want you reporting stories that reflect badly on what we are about to start doing.

Meaning, as they say, sources and methods, right? And we know what those turned out to be, the ugliness of it all, right? Jill Abramson, the Washington bureau chief at the Times at that moment, later the executive editor to no great result, recounted that conversation. And she said, we all readily agreed to cooperate. And she added, and indeed for many years, we never wrote anything that displeased the White House.

It was a very important moment. And I picked that time because that’s my date for the very sudden, abrupt end of the American century. Not everybody agrees with me, but that’s my date. It’s been making messes ever since in the aftermath. And at that moment, the gears shifted, so to speak, and the press got right on side the way they did in [Harry S.] Truman’s later years and through the 50s as a reenlisted soldier. That’s why I picked 2001.

Chris Hedges

Well, 2001 was finally, the rest of the world spoke to us in the language that we for decades had used to speak to them, which was death and explosions in a city skyline. And you’re right, and this is from your book on that issue,

“Their purpose turned subtly at first and then very plainly from informing the public

to protecting the institutions they purported to report upon from the public’s gaze.”

We should also note, although it’s not raised in your book, that this coincided with the economic downturn at media institutions and in particular major dailies so that their advertising revenues became so constricted and they became even more obsequious to the centers of power. You had written earlier that there was a place in the mainstream then, if not a large place, for journalists who held to the ideals, principles, and purpose that commonly draw people into the profession.

But I think the twin combination, and I was based in Paris and covered Al-Qaeda for the New York Times in Europe and the Middle East, and so was part of those discussions along with the odious Judy Miller at The New York Times, I would come back to New York for these meetings.

But they were all, it wasn’t that they were cynical, they were all true believers. And the French who did not want us to go into Iraq had given me massive access to very secret intelligence that they had in an effort, not because I was a great reporter, because it was The New York Times.

And I would come back with very hard information because Iraq, of course, had nothing to do with the attacks of 9/11, and it would just be dismissed. Well, that’s not what Dick Cheney told us, that’s not what Lewis “Scooter” Libby told us, that’s not Richard Perle…

So it was completely unquestioning. And as you write, the major dailies and the wire services routinely report the assertions of government officials as if these assertions alone were evidence of their veracity. And that is, of course, precisely what happened.

I want to talk about, it was a little thing but important that you picked up on, and it was this what you call this Jekyll and Hyde quality of… you were working for the International Herald Tribune, I was working for the New York Times, and I immediately knew what you were speaking about, and what it is is this split because these institutions pay deference to all of these values, journalistic independence and fearlessness and democracy dies in darkness or whatever.

But of course, it’s a masquerade. They are serving the centers of power. But for journalists who actually care about those values, it makes these institutions rife with anxiety. I had a colleague of great conscience who used to come into the New York Times and go to the bathroom and throw up every morning before he went to work. But that tension, that, and you do write about that within the institution, but I don’t want to let that go because I think it’s important.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah. You took me into the second of three themes I wanted to explore in the book and that’s reflected in the title, Journalists in Their Shadows, not to go too far into psychoanalysis, but I drew that from [Carl] Jung, okay, who argued we all have what he called shadows.

That part of ourselves that is obscured by social convention, orthodox morality, acceptance among peers, the professional coercions from employers and all that it creates in all of us something Jung called the shadow, the hidden self, the obscured self, right?

Now, my argument is that is exceptionally important, I can’t overstate this, exceptionally important in the case of journalists, because when they become, when their selves are divided, that’s when the compromises begin. It’s a psychological question. It’s a psychosocial question.

The corruptions in the press begin with the corruptions of the personalities who want to get paid, want to be promoted, and so on. And my argument, I call it disintegration. As I mentioned, the pastor in my little New England town taught me the relationship between two words, integration and integrity.

And working in the mainstream, I’m sure it was your experience, I’ll bet it was, that people become loyal to the orthodoxies imposed by employers. And they become so immersed in it, they don’t even know their condition of alienation from themselves, right? It’s a serious thing and a very serious phenomenon.

Now, the small place allowed for journalists and correspondents who were able to defend their ideals and principles, I had this experience myself, and I was encouraged to explore the thought by the late John Pilger, who is older than me by some years, but that was his experience too, right?

And he encouraged me to recognize it was there, but it closed out. It was never a large space, but it shut down. Again, after 2001, I think, is when that happened, right? It was never a generously proportioned section of the segment of the craft, but it was there. And suddenly it wasn’t there.

Chris Hedges

Yeah, it was there, but you were a management headache, and if you were not finally domesticated, they pushed you out. It was there, but none of these reporters had a long shelf life within, they certainly were not promoted within the institution.

Sydney Schanberg was a friend of mine from the killing fields and won the Pulitzer in Cambodia, came back, ran the Metro Desk, went after the big developers that were friends of the publisher, and he was finished. Abe Rosenthal, the editor, during that period, of the New York Times, used to call him my little commie. I just have to read this little description from the New York Times because, although I didn’t spend much time in the newsroom, I was hired by the foreign desk, spent seven months, which was enough, and then was back overseas.

“The 43rd Street newsroom,” that’s the old Times building, “turned out to be worse,” because you worked briefly for the New York Times as an editor, “turned out to be worse than my worst imaginings. Ill-will and bloody mindedness were ground into the worn industrial carpet. There was too much power at stake, my diagnosis, and too many people pursuing it too single-mindedly. Editors and reporters seemed to think solely of appearing clever out front where the managing editors sat. I could detect only slight interest in what was going on in the world and into the news pages. No wonder so many journalists forgetting why they were journalists were indifferent to or simply unaware of their place in the ideological order getting in, getting wise and getting out never seemed so fine an idea.”

This disintegration that you mentioned, and I’m sure you saw this, it breaks these people. By the time these reporters and editors who come in, with a certain, many of them with a certain amount of idealism, they are completely broken individuals. I mean, there’s a kind of [protagonist of Arthur Miller’s play “Death of a Salesman”] Willy Loman type quality to these guys in their 50s. They just have been destroyed by these institutions.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah. Again, it’s a psychological phenomenon. I reference this term of [Jean-Paul] Sartre’s, mauves fois, bad faith. They become reenactments of journalists. Newspapers are reenactments of newspapers. There’s a kind of meta quality to it. Two points, one, it’s endemic. People drawing salaries from the Wash Post or the Times, listening to this now would, I’m certain, would either not know what we were talking about, not because they’re immune to the phenomenon, but because they’re so far inside it they can’t see out, or they would deny it vehemently with the passionate conviction of converts, right? Because they have assumed the ideology of he who writes the checks, right?

I mentioned René Descartes in the book. I think, therefore I am becomes I am, therefore I think. I am a Washington Post reporter and therefore I think this, right? That’s how it works.

Second point here to rotate the perspective, this is why I don’t have a great deal of hope for the mainstream press, legacy press, however you wish to call it, coming good on all these questions. I think it’s a self-destructed institution and it’s why I put the considerable faith, if faith is the word, why I put considerable confidence in independent media as the source of the profession’s dynamism and future.

Chris Hedges

All of that is true, except of course the digital platforms that are now embedded in the national security state are using every, whether it’s algorithms or deplatforming or demonetizing to essentially stomp out independent media. I want to talk about another important point that you make having been a foreign correspondent, which you call the reality of difference. The making and maintaining of a psychological construct commonly called self and other, that is extremely important point in terms of how you report the world.

You also bring up the fact that large newspapers like the New York Times, they’ll never let you stay in a foreign bureau more than three to five years because of what you write about, this reality of difference. Explain what that is and why it buttresses not only our ignorance but a particular worldview.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, the reality of difference means very simply, American ideology, if I can use that blanket term, requires that we distinguish ourselves as the exceptional people on the face of the earth, and all others are in one measure “others”, right?

If you’re talking about the French or the British, okay, they are a friendly people, sympathetic people, but they are fundamentally different from us, you know? Their systems are different. Well, French have quite a good healthcare system, but that’s France, they’re different, right? When you get to non-Western people beginning at the top of the pyramid with the Japanese and on down, they are really very different.

And to report those sort of places, I, from the beginning of my career, was interested in non-Western countries, third world problems and all that. These people are profoundly, sort of, if I may say, otherized, right? And you report them as almost specimens, right? You report them from behind a pane of glass through which you will never pass.

And you mentioned that standard tour for a correspondent, three to five years, that’s right, because after that period, correspondents tend to understand the country or countries they’re reporting a little too well for the foreign editor’s taste, right?

Wait a minute, you’re actually writing about this country from their perspective, you’re showing us the world the way it looks to these people, no. If you were in Berlin, you got to go to Buenos Aires now, right? Start all over again. Don’t understand others too thoroughly.

Chris Hedges

Well, the point is you begin not only to understand them, you begin to understand us. And that’s what they don’t want.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, they’re all mirrors. Yeah, I mean, the correspondent, a good one, the light bulb goes on some years into an assignment. I am asking 1,000 questions. And as I get the answers, I’m learning about myself.

Chris Hedges

And there’s another aspect you lift up, which I think is important. You talk about how Western correspondents covering the non-West de-factualized the story. And you’re right about that. Explain what you mean by that.

Patrick Lawrence

Well, my experience was primarily, my formative years as a correspondent were late 70s, you know, the height of the Cold War, or maybe a little past its peak, but still a very serious reality, right? And I reported primarily in East Asia, not only in East Asia, but primarily.

And you had the dictatorships in Korea, Indonesia, the famous case of the Marcos’ in the Philippines, sort of, so to speak, strongman governments in Malaysia, places like that. And then the Japanese case, we reinvented the Japanese after the ‘45 defeat and installed the Liberal Democratic Party and made sure it stayed there and installed, right?

We couldn’t report these phenomena as they were. We couldn’t proceed into the zone of cause and effect, how did the South Korean dictators get there? How did Suharto get there in ‘65 when Sukarno, who, I love Sukarno, he was one of the great people of the 20th century, when he was deposed in a CIA operation, these things could not be discussed.

It was all about, in the case of the Japanese, the Japanese miracle, right? There was no miracle in Japan. It was what I call a Cold War social contract. America committed to buying the exports of all these countries. This is why the East Asians are so addicted to exports.

Committed to buying the exports of these countries so that they could make a social contract with their citizens that went this way: We will give you material prosperity. You can have a refrigerator or a color TV or a little tiny Japanese car, maybe for the first time in your family’s history, but you can’t touch politics. That’s the deal, right?

But you could watch this if you were alert and immune to the ideological ruts. You could understand it, but you couldn’t write about it.

Chris Hedges

This raises the other point and that is the absence of context, absence of history. I like Robert Fisk, I don’t if you knew Bob, he was a good friend of mine.

Patrick Lawrence

I didn’t know him, but I certainly knew of him.

Chris Hedges

Yeah, and his book, The Great War for Civilization, which is a great book on the modern Middle East, but it marries his reporting, he was in the Middle East for 44 years, it marries his reporting with his deep understanding of history.

But if you don’t understand the history, and nothing is contextualized, then when you get an eruption, for instance on October 7th by the Palestinians with incursion into Israel, because it’s not put in context, it’s presented within the media as incomprehensible, and with it, the people who carried it out become incomprehensible.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, I mean this happens, I don’t need to tell you Chris, this happens as a matter of daily routine as we speak, right? How many people have the context required to understand events in Syria these past couple of weeks? Not many. Context is in a sense, context in history.

I had a list of five things. Context, history, causality, agency, and responsibility are all essential for us to understand events in the world around us. And none is permitted to any effective extent in corporate media. Things happen, things happen out of nowhere. Why did that happen? Well, those other people, there’s no explaining them, right? It doesn’t make sense to us because we’re different from them, et cetera, right?

Here’s a good one. Here’s a perfect one for us. The “unprovoked” Russian military operation in Ukraine, unprovoked, unprovoked, unprovoked. That is the stripping out of history and context, plain and simple. In this case, it’s so boldly deceitful.

You don’t have to be a graduate student in history at the University of Wisconsin to know what went on before February 24th, 2022. 30 years of it, right? And then the coup in 2014, the eight years of bombardment, savage bombardment of Russian speakers in the East, it’s all there. But the media erase it with exceptional daring. And the force of media, the force of incessant presentation makes this kind of thing so regrettably effective. Yeah, that’s what we mean by context. Perfect example.

Chris Hedges

I want to talk about, you quote from the book, The Eclipse of Reason, “Reason as an organ for perceiving the true nature of reality and determining the guiding principles of our lives,” as [German philosopher and sociologist Max] Horkheimer writes, “has come to be regarded as obsolete. And you write, this surrender to the irrational does great damage to the surrendering society as is evident as we look out our windows. It is near to fatal for the practice of journalism.” Talk about that surrender to the irrational.

Patrick Lawrence

Okay, I like that book, Horkheimer’s book. It’s not a very long book. It’s a very accessible book if any of your listeners or reviewers are interested in finding it. You can find it on the used book sites, The Eclipse of Reason. What he was talking about, and this was 1947 that was published, listeners take note, that was the beginning of the Cold War, right?

He’s talking about the Socratic process of reasoning is you take a circumstance and you advance through the known universe of facts and evidence and you arrive at a conclusion. You are not in charge of the conclusion. What you learn on the way will lead you to the correct conclusion. This has been turned upside down in our hyper ideological polity such that you draw your conclusion first and then you reason backwards, Russiagate a perfect example.

This is how it has to come out. Now let’s reason backwards to support the conclusion we’ve already drawn. It’s a living disaster for our profession, given that we trade in facts and evidence and research.

As the wonderful Bob Perry put it, he’s in the book briefly, I don’t care what the truth is, I just care what the truth is. That’s out the window now. I care what the truth is, and I’m going to make a case to support my version of the truth. It’s not an operative way to conduct yourself as a journalist but pick up any major daily that’s what you’re reading.

Chris Hedges

I want to talk, it’s a small point, but it of course resonated with me because I’ve experienced it. They don’t ever embrace the ideology they promote, but the way that they censor, and you’re writing about one of your own experiences, you say stories written beyond the ideological fence posts are never thrown back for that reason. As the fence posts cannot be acknowledged, it is always, we want better sourcing or not enough solid reporting here or the catch-all you don’t support your case.

Patrick Lawrence

You must have… I can sense I’m ringing some of your bells here, right? I laid that out because any professional reading the book will say, oh my God, yeah, that, right? Look, I recounted one of my direct experiences when in my latter days at the Herald Tribune, the New York Times had bought out the Washington, it was a condominium ownership. The New York Times owned 50% and the Post owned 50%. Yeah.

Chris Hedges

Yeah, but let me just interrupt, Patrick. It was a good newspaper because it had editorial independence from both.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, and the head office was in Paris. It made a big difference. But anyway, the Times made the Post a very unpleasant offer it couldn’t refuse. And so the Times suddenly owned all of it.

Chris Hedges

Well, they threatened to destroy the Herald Tribune. Let’s be clear, it was like the mafia.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah. You know the story. And so the Times, the Trib, you know, it was one of those publications where there was that space we were discussing earlier. The Trib began the process of “Timesification.” And that is the occasion for the one experience I had. I had been editing the Asian edition. They took me off of that because they needed a Times man.

And they made me sort of a roving correspondent for the region. OK, I kind of thought my correspondent days were over, but I said, all right, let’s try this. And I wrote a story that I knew very, I thought, you better get this over with. You better determine once and for all who these people are.

I wrote a story for them that was a very good Herald Tribune story. No ideology, kind of a worldly perspective, not informed by any kind of nationalist orthodoxy. Just look at things the way they are. This is one reason I think the location of the Trib’s newsroom in Paris was important. Write that story and see what happens.

Chris Hedges

Let me just interrupt. It was a story about the decline of American influence and hegemony. The rise of what we call a multipolar world, in particular China.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, exactly. That’s right. Russia, China, Iran peripherally, you know, as I say in the book, I’ll eat my hat or anything else people propose if that story written in 2006 is not the world that’s out our windows today, right? So I wrote the story and I filed the story and it came back from my editor with all these, with all these not really objections, but do a little more work here.

As I say in the book, the piece was brass plated by the time I gave it to them because I knew it would face headwinds. My editor in Hong Kong finally gave up. I answered all his questions. So he sent it to Paris.

The newsroom in Paris raised all sorts of other questions. I answered those questions. They still didn’t want to publish it. They sent it to New York. And then the foreign editor, some national security correspondents whose name I’d love to mention but won’t, and some bureau chiefs in Asia had a look at it, right? Now, the conflicts of interest are glow in the dark.

I had a story they didn’t have. And they went on and on about, one of them said, tired old sources. Another one said what I said and what I repeated in the book, poorly sourced, can’t tell what it’s about and so on. And finally it popped out the other end of the pipeline from my editor in Hong Kong: Patrick, we just can’t run this. That’s all. We just can’t run this. You’re talking about the upper echelons of American journalism.

As I say in the book, I have a great affection for that phrase ever since, the upper echelons of American journalism. That’s what happens. Nobody at any time, this is your point, nobody at any time could say, Patrick, this is not the orthodoxy. We’re defending American primacy here and you’re questioning it. That was the rub. But that can’t be said, right?

Chris Hedges

Sy Hirsch wrote a great memoir, Reporter, which everyone should read, but he recounts exactly a long investigative piece he did on Gulf and Western. Very similar process, he left the paper not long after that.

But before we close, I want to ask, because I have a slight disagreement with you, you hold up WikiLeaks, the coverage of the Vietnam War, Watergate, all as moments of integrity, that may not be your word, in American journalism. I don’t.

The Vietnam War, for me, the coverage changed once public opinion changed. The press is a reactive force that doesn’t lead in terms of Watergate. All of those tactics, this is Noam Chomsky, had been used on anti-war groups and dissidents, the Black Panthers including assassinating Fred Hampton. But the press didn’t care about it until the elite started devouring their own, i.e. the Republican administration of Nixon went after the Democratic Party.

And in the case of WikiLeaks, and I was at the New York Times, I think that they were shamed that by not publishing the revelations of WikiLeaks, they would have been exposed for who they were. They did, though, that publication, a collaboration with Julian Assange with their teeth grit and knew the moment the ink was dry, their next step was to destroy Julian Assange.

Comment briefly on that and then I want to talk about where we’re going.

Patrick Lawrence

Okay, okay. Yeah, I understand. I mean, what you seem to be saying is the political environment counted in all of these cases. Watergate would not have happened if considerable factions of the Washington power elite had turned against Nixon.

The coverage we in the profession and others I suppose admire from Vietnam, [David] Halberstam, Malcolm Brown, [inaudible] and all those people. I don’t think that coverage would have come to be if considerable portions of the power elite in Washington, the policy cliques and of course the anti-war movement hadn’t turned against the war. That’s what I mean by political environment counts.

WikiLeaks, I hadn’t thought of it the way you do, they were embarrassed. I remember in autumn of 2010 when there was a big release of WikiLeaks documents. Forgive me, I can’t remember which ones they were.

Chris Hedges

2010 were the Iraqi war logs.

Patrick Lawrence

Yeah, okay. I remember on the front page of the Times, David Sanger, happy to mention his name, acknowledged that The Times has checked with the administration to make sure of what we can publish and what we can’t. You tell that story later on, people can’t believe it, but it was there and it’s, in fact, it’s routine, okay? I think the key, I had it a little differently than you. I thought, I took it that the corporate media, mainstream press, saw in the Assange operation a real change in what journalism could be. But I think you might be closer to the mark. They had no choice.

The key moment, I think, is when [Mike] Pompeo, the odious Pompeo, gave a speech at CSIS [Center for Strategic and International Studies], I think, and called Assange a Russian actor, all these phrases they make up, and turned on him. That was, forgive me my dates, 2011, 2012, so that’s when the media turned and said, okay, we can go after this guy now. And he became a sort of, as I recount in the book, a sort of sacred outcast, right? And they went right to town on Assange, just in the way you have suggested.

Chris Hedges

Well, WikiLeaks threatened their entire model of journalism. I mean, they had to destroy them. And I can tell you, because I know, I was inside with Bill Keller and all these other… They hated, hated Assange.

Patrick Lawrence

Were you still inside the paper at that time?

Chris Hedges

In 2010, no. But of course I know all these people. I mean, I know them and well. Keller was my foreign editor before he became executive editor. No, they had a vested interest in the moment it was published in destroying Julian. I want to talk about independent media. Independent media has always been the check on the commercial press.

That goes back to Ida B. Wells and before the great crusading journalists set up her newspaper in Memphis that exposed the reality of lynching, which was nothing about Black men sexually assaulting white women. As she pointed out in her investigations, it was about destroying the Black doctors, Black business owners to enforce the poverty and subjugation of a segregated South.

Ramparts, you mentioned Bob Scheer, again, Ramparts never made a dime, COINTELPRO and that photograph of the child running down the road being burned by napalm in Vietnam and all of this comes out in the alternative press. We used to have the Village Voice. We used to have a decentralized press, so there were far more alternative weeklies. It’s always been the independent media that has shamed or forced the commercial media to begrudgingly accept reality.

That’s been transferred to the digital age, and you hold up Consortium News and other sites that I respect, run by Joe Lauria, founded by Bob Perry. I knew Bob because I covered the Contra War in Nicaragua. And you’re right, that that is where the hope lies, but I think the hope has always been within the alternative media.

And you write about working for an alternative media publication which held these values, it was called The Guardian, if I remember. But we’re watching it play itself out now in the digital age. And we’re watching the heavy-handed state censorship move quite aggressively to crush it. I mean, I think that’s where we are.

I’m a little less hopeful than you are. I’m hopeful about the quality of the independent media and what can come out. But I think that the ferocity of the censorship is almost daily becoming more and more pronounced. And I speak as somebody who’s been deplatformed, demonetized, hit with algorithms and everything else.

Patrick Lawrence

Yes, I know. Well, a couple of points. I think of, first of all, in the book, I discard the term alternative media, right?

Chris Hedges

Yeah, you were right to do so.

Patrick Lawrence

Way back in my youth, I was foreign editor at The Guardian, The American Guardian, one of the wonderful experiments of 20th century journalism. It lost its way in sectarian nonsense. My argument now is that independent media should not understand itself, and nor should its readers and viewers, as an alternative to anything.

It should be an autonomous, freestanding set of institutions, publications, whatever, broadcasters, that find their own way, and they’re not qualifying what they read in the New York Times the previous day. I think that’s an important point, the independence in the true sense of the term.

Second point I want to make here is what we’re talking about, the way you and I are talking right now, I don’t know your technology intimately, it is dependent on these extraordinary digital technologies. That’s terrific. Look at the explosion in independent media. You don’t have to bother with newsprint anymore and all that sort of thing, right? It’s out there right away. But this is the weighty paradox of our time.

What has made independent media so extraordinarily effective over a very long period of time and make no mistake, the corporate press is quite concerned about the challenge with which they’ve been presented. But these same technologies leave us extremely vulnerable to being shut down, as you were saying, censored. They can pull the plug.

My reply to this, and I don’t wish to sound angelic or idealist, is think about the human commitment to renewed ideals evidenced in all the good people in independent media. That’s human intellectual commitment, career on the line sort of stuff. You might destroy the technology. Joe [Lauria] just got finished cleaning up this grotesque hack of the entire Consortium’s website. You might do that, but you’re not gonna destroy the spirit and commitment of the people doing this work. And it’s from that I draw a measure of optimism you may not share. Whatever happens, we’ll do this.

Chris Hedges

No, I share that. I mean, I think the digital media has given us a kind of reach that normally dissidents such as ourselves wouldn’t have, independent journalists. I remember, I.F. Stone began his weekly printing it off in his basement.

Patrick Lawrence

I thought it was his dining table.

Chris Hedges

Was it? I thought maybe it was his dining table. I don’t know. But look, it had… And he made the large journalistic institutions shake and quake because I think that circulation was never above 60,000, but it didn’t matter, it was who it reached.

Patrick Lawrence

I love this detail, who told us this? Who told this story? Wash Post reporters would be on the bus in DC with the Post in front of them and I.F, Stone’s Weekly inside. Fun.

Chris Hedges

I didn’t know that. That’s great. All right. Well, thanks so much. You were wonderful. I want to thank Diego [Ramos], Max [Jones], Thomas [Hedges], and Sofia [Menemenlis], who produced the show. You can find me at ChrisHedges.Substack.com.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mSbFTXkCa-M

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jW6-BcMwpfY

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 Jun 2025 - 5:45am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

newsporky.....

Newsweek has issued a correction after publishing a report that inaccurately attributed a demand by a senior Russian official for NATO to withdraw troops from the Baltic states.

The original article, published earlier this week, carried the headline: “Russia won’t end Ukraine war until NATO ‘pulls out’ of Baltics: Moscow.” The report cited Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov and suggested he had directly called for NATO to leave Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as a condition for ending the conflict in Ukraine.

However, Ryabkov made no specific mention of the Baltics in the interview cited by Newsweek. His comments, published by the Russian news agency TASS, referenced NATO’s military posture in “Eastern Europe,” not the Baltic region by name.

Following criticism – including from Latvia’s ambassador to NATO, Maris Riekstins, who called the report “very strange” – Newsweek updated both the article’s headline and its content. A disclaimer was added noting that the piece had been “updated to reflect that Sergei Ryabkov did not reference the Baltic states.”

Despite the correction, the initial version of the story circulated widely and was picked up by other media outlets, including Lithuania’s state broadcaster LRT. Some of these reports included additional commentary from Baltic officials expressing concern over potential Russian aggression toward the region – a claim Moscow has repeatedly denied.

In the TASS interview, Ryabkov reiterated Moscow’s longstanding opposition to NATO expansion near Russia’s borders and called for “legally binding” security guarantees. He said that “reducing NATO’s contingent in Eastern Europe would probably benefit the security of the entire continent,” but did not single out any country.

“The American side requires practical steps aimed at eliminating the root causes of the fundamental contradictions between us in the area of security,” Ryabkov said. “Among these causes, NATO expansion is in the foreground.”

READ MORE: German foreign intelligence chief claims Russia could attack NATOHe also insisted that resolving the Ukraine conflict and normalizing Russia’s relations with the West would require addressing what he called Russia’s “fundamental interests,” including opposition to the deployment of strike weapons near its territory.

Russia’s position on NATO enlargement has been a central issue in its conflict with Ukraine, and Russian officials have frequently cited Western military support for Kiev as a destabilizing factor. However, suggestions that Moscow has issued explicit threats to the Baltics are not supported by Ryabkov’s latest remarks.

https://www.rt.com/russia/619106-ryabkov-newsweek-misquote-nato/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

from 2000.....

Robert W. McChesney, coeditor of Monthly Review from 2000-2004 and a member of the board of directors of the Monthly Review Foundation from 2000-2025, died on March 25, 2025. We will publish a memorial tribute to him and his life and work in a future issue of MR.

Journalism, democracy, … and class struggle

By Robert W. McChesney (Posted Apr 02, 2025)

Originally published: Monthly Review on November 1, 2000

Socialists since the time of Marx have been proponents of democracy, but they have argued that democracy in capitalist societies is fundamentally flawed. In capitalist societies, the wealthy have tremendous social and economic advantages over the working class that undermine political equality, a presupposition for viable democracy. In addition, under capitalism the most important economic issues—investment and control over production—are not the province of democratic politics but, rather, the domain of a small number of wealthy firms and individuals seeking to maximize their profit in competition with each other. This means that political affairs can only indirectly influence economics, and that any party or individual in power has to be careful not to antagonize wealthy investors so as to instigate an investment strike and an economic collapse that would generally mean political disaster.

For socialists, the purpose of class politics is to eliminate class exploitation, poverty, and social inequality and to lay the foundation for a genuine democracy, where people truly rule their own lives. The strategy and tactics best suited to accomplishing these goals have been the subject of tremendous debate among socialists, but the goals have almost always been the same. For most of their history, socialists have been at the forefront of movements to extend the franchise and the scope of democracy, both within capitalist societies and extending beyond capitalist property relations.

A central concern in democratic theory of all stripes is how people can have the information, knowledge, and forums for communication and debate necessary to govern their own lives effectively. The solution to this problem is found, in theory, in systems of education and media. But then the nature of the educational and media systems comes into focus as a crucial issue. If these systems are flawed and undermine democratic values, it is awfully difficult to conceive of a viable democratic society. Therefore, public debates over education and media policy are central to debates over the nature of democracy in any given society. Today, for example, the United States is in the midst of a massive campaign by the political right to privatize education, effectively dismantling public education systems, making the system explicitly class-based, and subjecting education for the non-elite to commercial values. The antidemocratic implications of these developments can hardly be exaggerated.

The situation is even more severe for democratic values in media, though this receives far less attention in the official political culture. In particular, journalism is that product of the media system that deals directly with political education. Within democratic theory, there are two indispensable functions that journalism must serve in a self-governing society. First, the media system must provide a rigorous accounting of people in power and people who want to be in power, in both the public and private sector. This is known as the watchdog role. Second, the media system must provide reliable information and a wide range of informed opinions on the important social and political issues of the day. No single medium can or should be expected to provide all of this; but the media system as a whole should provide easy access to this for all citizens. Unless a society has a journalism that approaches these goals, it can scarcely be a self-governing society of political equals.

By these criteria, the U.S. media system is an abject failure. It serves as a tepid and weak-kneed watchdog over those in power. And it scarcely provides any reliable information or range of debate on most of the basic political and social issues of the day. As Jeff Cohen, the founder of Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), puts it, on those issues covered the range of debate extends from General Electric (GE) to General Motors (GM). The media system is, in short, an antidemocratic force. But that should not surprise us. The media system in the United States does not exist to serve democracy, it exists to generate maximum profit to the small number of very large firms and billionaire investors. It does this job very well. So, in media, we see the core contradiction of our age, where the democratic interests of the many are undermined by the private selfish interests of the powerful few.

The Rise and Fall of Professional JournalismMuch discussion of journalism is predicated on a notion that it is a professional enterprise, politically neutral in tone, and independent of commercial values. This is a fairly recent notion historically, so let’s put it in context. Although in many respects the problem of the media for democracy is more important today than ever before, it is a problem as old as democracy itself. When the U.S. constitution was drafted in 1789, it included explicit provisions regarding copyright, so as to balance the interests of authors with those of the broader community for inexpensive information. When the First Amendment was passed two years later, it included the specific protection of a free press (in addition to several other core freedoms, including speech and assembly). The concern was that the dominant political party or faction would outlaw opposition newspapers—all newspapers were partisan in orientation at the time—unless they were prohibited from doing so, as was then the common practice in Europe. If there could be no dissident press, there could be no democracy. Karl Marx, who supported himself for much of his life as a journalist, was a steadfast proponent of this notion of a free press.

During the nineteenth century, the press system remained explicitly partisan but it increasingly became an engine of great profits as costs plummeted, population increased, and advertising—which emerged as a key source of revenues—mushroomed. The commercial press system became less competitive and ever more clearly the domain of wealthy individuals, who usually had the political views associated with their class. Throughout this era, socialists, feminists, abolitionists, trade unionists, and radicals writ largetended to regard the mainstream commercial press as the mouthpiece of their enemies, and established their own media to advance their interests. Indeed, the history of the left and left media during this period are almost interchangeable.

The twentieth century, with the rise of monopoly capital, witnessed a sea change in U.S. media. On the one hand, the dominant newspaper industry became increasingly concentrated into fewer massive chains and all but the largest communities only had one or two dailies. The economics of advertising-supported newspapers erected barriers to entry that made it virtually impossible for small, independent newspapers to succeed, despite the protection of the constitution for a “free press.” At the same time, new technologies helped pave the way for the commercial development of national magazines, recorded music, film, radio, and, later, television as major industries. These all became highly concentrated industries and engines of tremendous profits. (By 2000, the largest media and communication firms rank among the largest firms in the economy.)

At the beginning of the twentieth century these developments led to a crisis of sorts for U.S. media—or the press, as it was then called. Commercial media were coming to play a larger and larger role in people’s lives (and by 1999, media consumption would increase to more than eleven hours per day for the average American) yet the media industries were increasingly the province of a relatively small number of large commercial concerns operating in noncompetitive markets. The era of the viable “alternative” press was in rapid retreat. The First Amendment promise of a “free press” was being altered fundamentally. What was originally meant as a protection for citizens effectively to advocate diverse political viewpoints was being transformed into commercial protection for media corporation investors and managers in noncompetitive markets to do as they pleased to maximize profit with no public responsibility.

In particular, the rise of the modern commercial press system drew attention to the severe contradiction between a privately held media system and the needs of a democratic society, especially in the provision of journalism. It was one thing to posit that a commercial media system worked for democracy when there were numerous newspapers in a community, when barriers to entry were relatively low, and when immigrant and dissident media proliferated widely, as was the case for much of the nineteenth century. For newspapers to be partisan at that time was no big problem because there were alternative viewpoints present. It was quite another thing to make such a claim by the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when all but the largest communities only had one or two newspapers, usually owned by chains or very wealthy and powerful individuals. For journalism to remain partisan in this context, for it to advocate the interests of the owners and the advertisers who subsidized it, would cast severe doubt on the credibility of the journalism. As Henry Adams put it at the time, “The press is the hired agent of a monied system, set up for no other reason than to tell lies where the interests are concerned.” In short, it was widely thought that journalism was explicit class propaganda in a war with only one side armed. Such a belief was very dangerous for the business of newspaper publishing, as many potential readers would find it incredible and unconvincing.

It was in the cauldron of controversy, during the Progressive era, that the notion of professional journalism came of age. Savvy publishers understood that they needed to have their journalism appear neutral and unbiased, notions entirely foreign to the journalism of the era of the Founding Fathers, or their businesses would be far less profitable. Publishers pushed for the establishment of formal “schools of journalism” to train a cadre of professional editors and reporters. None of these schools existed in 1900; by 1915, all the major schools such as Columbia, Northwestern, Missouri, and Indiana were in full swing. The notion of a separation of the editorial operations from the commercial affairs—termed the separation of church and state—became the professed model. The argument went that trained editors and reporters were granted autonomy by the owners to make the editorial decisions, and these decisions were based on their professional judgment, not the politics of the owners and the advertisers, or their commercial interests to maximize profit. Readers could trust what they read. Owners could sell their neutral monopoly newspapers to everyone in the community and rake in the profits.

Of course, it took decades for the professional system to be adopted by all the major journalistic media. The first half of the twentieth century is replete with owners like the Chicago Tribune‘s Colonel McCormick, who used their newspapers to advocate their fiercely partisan (and, almost always, far-right) views. (McCormick’s Tribune was so reactionary that when Hitler came to power, the Tribune‘s European correspondent defected to work for the Nazi propaganda service.) And it is also true that the claim of providing neutral and objective news was suspect, if not entirely bogus. Decision-making is an inescapable part of the journalism process, and some values have to be promoted when deciding why one story rates front-page treatment while another is ignored.

Specifically, the realm of professional journalism had three distinct biases built into it, biases that remain to this day. First, to remove the controversy connected with the selection of stories, it regarded anything done by official sources, e.g. government officials and prominent public figures, as the basis for legitimate news. This gave those in political office (and, to a lesser extent, business) considerable power to set the news agenda by what they spoke about and what they kept quiet about. It gave the news a very establishment and mainstream feel. Second, also to avoid controversy, professional journalism posited that there had to be a news hook or a news peg to justify a news story. This meant that crucial social issues like racism or environmental degradation fell through the cracks of journalism unless there was some event, like a demonstration or the release of an official report, to justify coverage. So journalism tended to downplay or eliminate the presentation of a range of informed positions on controversial issues. This produces a paradox: journalism which, in theory, should inspire political involvement tends to strip politics of meaning and promote a broad depoliticization.

Both of these factors helped to stimulate the birth and rapid rise of the public-relations (PR) industry, the purpose of which was surreptitiously to take advantage of these two aspects of professional journalism. By providing slick press releases, paid-for “experts,” ostensibly neutral-sounding but bogus citizens groups, and canned news events, crafty PR agents have been able to shape the news to suit the interests of their mostly corporate clientele. Or as Alex Carey, the pioneering scholar of PR, put it, the role of PR is to so muddle the public sphere as to “take the risk out of democracy” for the wealthy and corporations. PR is welcomed by media owners, as it provides, in effect, a subsidy for them by providing them with filler at no cost. Surveys show that PR accounts for anywhere from 40 to 70 percent of what appears as news.

The third bias of professional journalism is more subtle but most important: far from being politically neutral, it smuggles in values conducive to the commercial aims of the owners and advertisers as well as the political aims of the owning class. Ben Bagdikian, author of The Media Monopoly, refers to this as the “dig here, not there” phenomenon. So it is that crime stories and stories about royal families and celebrities become legitimate news. (These are inexpensive to cover and they never antagonize people in power.) So it is that the affairs of government are subjected to much closer scrutiny than the affairs of big business. And of government activities, those that serve the poor (e.g., welfare) get much more critical attention than those that serve primarily the interests of the wealthy (e.g., the CIA and other institutions of the national security state), which are strictly off-limits. The genius of professionalism in journalism is that it tends to make journalists oblivious to the compromises with authority they routinely make.

Professional journalism hit its high water mark in the United States from the 1950s into the 1980s. During this era, journalists had relative autonomy to pursue stories and considerable resources to use to pursue their craft. But there were distinct limitations. Even at its best, professionalism was biased toward the status quo. The general rule in professional journalism is this: if the elite, the upper 1 or 2 percent of society who control most of the capital and rule the largest institutions, agree on an issue then it is off-limits to journalistic scrutiny. Hence, the professional news media invariably take it as a given that the United States has a right to invade any country it wishes for whatever reason it may have. While the U.S. elite may disagree on specific invasions, none disagrees with the notion that the U.S. military needs to enforce capitalist interests worldwide. Similarly, U.S. professional journalism equates the spread of “free markets” with the spread of democracy, although empirical data show this to be nonsensical. To the U.S. elite, however, democracy is defined by their ability to maximize profit in a nation, and that is, in effect, the standard of professional journalism. In sum, on issues such as these, U.S. professional journalism, even at its best, serves a propaganda function similar to the role of Pravda or Izvestia in the old USSR.

The best journalism of the professional era came (and still comes) in the alternative scenarios: when there were debates within the elite or when an issue was irrelevant to elite concerns. So important social issues, like civil rights or abortion rights or conflicts between Republicans and Democrats (such as Watergate), tended to get superior coverage to issues of class or imperialism, like the weakening of progressive income taxation, the size and scope of the CIA’s operations, or U.S.-sponsored mass murder in Indonesia. But one should not exaggerate the amount of autonomy journalists had from the interests of owners, even in this “golden age.” In every community there was a virtual Sicilian Code of silence, for example, regarding the treatment of the area’s wealthiest and most powerful individuals and corporations. Media owners wanted their friends and business pals to get nothing but kid-gloves treatment in their media and so it was, except for the most egregious and boneheaded maneuver.

The professional autonomy of U.S. journalism, limited as it was, came under sustained attack in the 1980s and after nearly two decades is only a shell of its former self. The primary reason for this is that, beginning in the 1980s, the relaxation of federal ownership regulations and new technologies made vastly larger media conglomerates economically feasible and, indeed, mandatory. Today some seven or eight firms dominate the U.S. media system, owning all the major film studios, music companies, TV networks, cable TV channels and much, much else. Another fifteen or so companies round out the system; between them they own the overwhelming preponderance of media that Americans consume. As nearly all the traditional news media became small parts of vast commercial empires, owners logically cast a hard gaze at their news divisions and determined to generate the same sort of return from them that they received from their film, music, and amusement park divisions. This meant laying off reporters, closing down bureaus, using more free PR material, emphasizing inexpensive trivial stories, focusing on news of interest to desired upscale consumers and investors, and generally urging a journalism more closely tuned to the bottom-line needs of advertisers and the parent corporation. The much-ballyhooed separation of church and state was sacrificed on the altar of profit.

This has meant that all the things professional journalism did poorly in its heyday, it does even worse today. And those areas where it had been adequate or, at times, more than adequate, have suffered measurably. Empirical studies chronicle the decline of journalism in numbing detail. Perhaps the most striking indication of the collapse of professional journalism comes from the editors and reporters themselves. As recently as the mid 1980s, professional journalists tended to be stalwart defenders of the media status quo, and they wrote book after book of war stories celebrating their vast accomplishments. Today the thoroughgoing demoralization of journalists is striking and palpable. One need only go to a bookstore to see title after title by prominent journalists lamenting the decline of the craft due to corporate and commercial pressure. As Jim Squires, former editor of the Chicago Tribune put it, our generation has witnessed the “death of journalism.”

Journalism as Ideological Class WarfareAll of this suggests that contemporary journalism poses a severe problem for the left and democratic forces. It is the class bias that is the biggest obstacle. In the 1940s, most medium- and large-circulation daily newspapers had fulltime labor-beat reporters, sometimes several of them. The coverage was not necessarily favorable to the labor movement, but it existed. Today there are less than ten fulltime labor reporters in the media; coverage of working-class economic issues has all but ceased to exist in the news. Conversely, mainstream news and “business news” have effectively morphed over the past two decades as the news is increasingly pitched to the richest one-half or one-third of the population. The affairs of Wall Street, the pursuit of profitable investments, and the joys of capitalism are now presented as the interests of the general population. Journalists rely on business or “free market”-loving, business-oriented think tanks as sources when covering economics stories.

The dismal effects of this became clear in 1999 and 2000 when there were enormous demonstrations in Seattle and Washington, D. C. to protest meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Here, finally, was the news hook that would permit journalists to examine what may be the most pressing political issues of our time. The coverage was skimpy, and paled by comparison to the round-the-clock treatment of the John F. Kennedy, Jr., plane crash. News coverage of the demonstrations tended to emphasize property damage and violence and, even there, it downplayed the activities of the police. There were, to be fair, some outstanding pieces produced by the corporate media, but those were the exceptions to the rule. The handful of good reports that did appear were lost in the continuous stream of procapitalist pieces. In addition to relying upon probusiness sources, it is worth noting that media firms are also among the leading beneficiaries of these global capitalist trade deals, which helps explain why their coverage of them throughout the 1990s was so decidedly enthusiastic. The sad truth is that the closer a story gets to corporate power and corporate domination of our society, the less reliable the corporate news media are.

It is also worth noting that the WTO demonstrations launched a troubling degeneration of media coverage of large public demonstrations that grew worse in Washington in April 2000 and at the Republican and Democratic conventions this summer. By the time of the conventions, demonstrators were being ignored altogether in the press or treated with contempt. As police in Philadelphia and Los Angeles effectively terminated the right of free assembly for Americans, the corporate news media regurgitated the press releases of the police and of the spinmeisters inside the convention halls. Even by the deplorable standard of news coverage of antiwar demonstrations in the 1960s and 1970s, this was a striking lack of concern for the termination of elementary civil liberties.

In recent years, this increased focus by the commercial news media on the more affluent part of the population has reinforced and extended the class bias in the selection and tenor of material. Stories of great importance to tens of millions of Americans will fall through the cracks because those are not the “right” Americans, according to the standards of the corporate news media. Consider, for example, the widening gulf between the richest 10 percent of Americans and the poorest 60 percent of Americans that has taken place over the past two decades. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, real income declined or was stagnant for the lower 60 percent, while wealth and income for the rich skyrocketed. By 1998, discounting home ownership, the top 10 percent of the population claimed 76 percent of the nation’s net worth, and more than half of that is accounted for by the richest 1 percent. The bottom 60 percent has only a minuscule share of total wealth, aside from some home ownership; by any standard, the lowest 60 percent is economically insecure, weighed down as it is by very high levels of personal debt.

As Lester Thurow notes, this peacetime rise in class inequality may well be historically unprecedented and is one of the main developments of our age. It has tremendously negative implications for our politics, culture, and social fabric, yet it is barely noted in our journalism—except for rare mentions when the occasional economic report points to it. One could say that this can be explained by the lack of a news peg that would justify coverage, but that is hardly tenable when one considers the cacophony of news media reports on the economic boom of the past decade. In the crescendo of news media praise for the genius of contemporary capitalism, it is almost unthinkable to criticize the economy as deeply flawed. To do so would seemingly reveal one as a candidate for an honorary position in the Flat-Earth Society. TheWashington Post has gone so far as to describe ours as a nearly “perfect economy.” And it does, indeed, appear more and more perfect the higher one goes up the socioeconomic ladder, which points to the exact vantage point of the corporate news media.

For a related and more striking example, consider one of the most astonishing trends lately, one that receives little more coverage than O. J. Simpson’s boarder Kato Kaelin’s attempts to land a job or a girlfriend: the rise of the prison-industrial complex and the incarceration of huge numbers of people. The rate of incarceration has more than doubled since the late 1980s, and the United States now has five times more prisoners per capita than Canada and seven times more than Western Europe. The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. Moreover, nearly 90 percent of prisoners are jailed for nonviolent offenses, often casualties of the so-called drug war.

The sheer quantity of prisoners is not even half of it. Recent research suggests that a significant minority of those behind bars may well be innocent. Consider the state of Illinois, where, in the past two decades, more convicted prisoners on death row have been found innocent of murder than have been executed. Or consider the recent published work of the Innocence Project, which has used DNA testing to get scores of murder and rape convictions overturned. In addition, the conditions inside the prisons themselves tend far too often to be reprehensible and grotesque, in a manner that violates any humane notion of legitimate incarceration. It should be highly disturbing and the source of public debate for a free society to have so many people stripped of their rights. Revolutions have been fought and governments have been overthrown for smaller affronts to the liberties of so many citizens. Instead, to the extent that this is a political issue, it is a debate among Democrats and Republicans over who can be “tougher” on crime, hire more police, and build more prisons. Almost overnight, the prison-industrial complex has become a big business and a powerful lobby for public funds.

This is an important story, one thick with drama and excitement, corruption and intrigue. In the past two years, several scholars, attorneys, prisoners, and freelance reporters have provided devastating accounts of the scandalous nature of the criminal justice system, mostly in books published by small, struggling presses. Yet this story is hardly known to Americans who can name half the men Princess Diana had sex with or the richest Internet entrepreneurs. Why is that? Well, consider that the vast majority of prisoners come from the bottom quarter of the population in economic terms. It is not just that the poor commit more crimes; the criminal justice system is also stacked against them. “Blue-collar” crimes generate harsh sentences while “white-collar” crime—almost always netting vastly greater amounts of money—gets kid-gloves treatment by comparison. In 2000, for example, a Texas man received sixteen years in prison for stealing a Snickers candy bar, while, at the same time, four executives at Hoffman-LaRoche Ltd. were found guilty of conspiring to suppress and eliminate competition in the vitamin industry, in what the Justice Department called perhaps the largest criminal antitrust conspiracy in history. The cost to consumers and public health is nearly immeasurable. The four executives were fined anywhere from seventy-five thousand dollars to 350,000 dollars and they received prison terms ranging from three months all the way up to…four months.

Hence, the portion of the population that ends up in jail has little political clout, is least likely to vote, and is of less business interest to the owners and advertisers of the commercial news media. It is also a disproportionately nonwhite portion of the population, and this is where class and race intersect and form their especially noxious American brew. Some 50 percent of U.S. prisoners are African-American. In other words, these are the sort of people that media owners, advertisers, journalists, and desired upscale consumers do everything they can to avoid, and the news coverage reflects that sentiment. As Barbara Ehrenreich has observed, the poor have vanished from the view of the affluent; they have all but disappeared from the media. And in those rare cases where poor people are covered, studies show that the news media reinforce racist stereotypes, playing into the social myopia of the middle and upper classes. There is ample coverage of crime in the news media, but it is used to provide inexpensive, graphic, and socially trivial filler. The coverage is almost always divorced from any social context or public policy concerns and, if anything, it serves to enhance popular paranoia about crime waves and prod political support for tough-talking, “three strikes and you’re out” programs.