Search

Recent comments

- success....

7 hours 15 min ago - seriously....

9 hours 59 min ago - monsters.....

10 hours 6 min ago - people for the people....

10 hours 43 min ago - abusing kids.....

12 hours 16 min ago - brainwashed tim....

16 hours 36 min ago - embezzlers.....

16 hours 42 min ago - epstein connect....

16 hours 53 min ago - 腐敗....

17 hours 13 min ago - multicultural....

17 hours 19 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

of courage and delusions....

The forms of 19th-century European fictions, including the Russian, have a powerful relation to older Christian stories, from the Bible to Bunyan. The novels meet the old tales with part parody, part dialogue, part rejection and reconstruction.

The Idiot

by Fyodor Dostoevsky, translated by David McDuff

Middlemarch opens with a paradigm of its heroine as a "later-born" St Theresa, "helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul". Dorothea's virtue cannot find a form in her modern world. Unlike Eliot, Dostoevsky was Christian, and increasingly passionate about preserving faith. DH Lawrence, another maker of fictive prophecies and apocalypses, was reading The Idiot in 1915. "I don't like Dostoevsky," he wrote. "He is like the rat, slithering along in hate, in the shadows, and in order to belong to the light professing love, all love." It had become, he shrilled, "a supreme wickedness to set up a Christ worship as Dostoevsky did: it is the outcome of an evil will..."

The central idea of The Idiot as we have it was, as Dostoevsky wrote in a letter, "to depict a completely beautiful human being". Prince Myshkin is a Russian Holy Fool, a descendant of Don Quixote, and a type of Christ in an un-Christian world. Author and character face the problem all good characters face in all novels — good in fiction is just not as interesting as wickedness, and runs the risk of repelling readers, even those less worked up than Lawrence. There is another problem - goodness tends to mean unselfishness, and unselfishness tends to lack sexual energy, another great driving force in fictions. In the letter quoted above, written in 1868 as Dostoevsky was writing and sending out the first chapters of the novel, he acknowledges uneasily that he has seized this ambitious project prematurely, out of financial and professional desperation.

The writing and publication of the novel were certainly both tortured and strained. It was written abroad, unlike his previous novels, for serial publication, put together by his second wife and stenographer, Anna Grigoryevna. Their daughter died during the writing. Dostoevsky gambled suicidally and had epileptic fits. Anna preserved the notebooks, which show that both plot and characters were in a state of fluid and volcanic chaos, even while the book was appearing. The good prince appears in the early notes as proud and demonic, and the rapist of his adopted sister (a prototype of Nastasya Filippovna). He also commits arson and wife-murder. The first part of the novel, as it appeared, is acknowledged to be powerful. Dostoevsky appears not to have had a clear idea of how to proceed. The second two parts are phantasmagoric and rambling, unplotted and fitfully energetic.

John Jones, in his excellent study of Dostoevsky, rejects The Idiot as a major work on the grounds that, alone among Dostoevsky's novels, it does not have the intricate tissue of language and punning Jones makes available to non-Russian readers. Other critics complain that the "good" prince makes everyone's life worse and achieves nothing — though in this he may be compared to the resurrected Christ of Ivan Karamazov's fable of the Grand Inquisitor. The world does not know what to do with him.

I think The Idiot to be a masterpiece — flawed, occasionally tedious or overwrought, like many masterpieces — but a fact of world literature just as important as the densely dramatic Brothers Karamazov or the brilliantly subtle and terrifying Devils. In those two novels, as in the simpler Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky had plots and political and religious ideas working together. In The Idiot he is straining to grasp a story and a character converting themselves from Gothic to Saint's Life on the run. What makes the greatness is double — the character of the prince, and a powerful series of confrontations with death. The true subject of The Idiot is the imminence and immanence of death. The image of these things is Holbein's portrait of Christ taken down from the cross, a copy of which hangs in Rogozhin's house, and which was seen by both Dostoevsky and Prince Myshkin in Basle. It represents, we are told, a dead man who is totally flesh without life, damaged and destroyed, with no hint of a possible future resurrection. The form of the novel is shaped by the inexorable outbreak of Dostoevsky's deepest preoccupations. It is the quality of Dostoevsky's doubt and fear that is the intense religious emotion in this novel — to which Lawrence was no doubt reacting.

I had known, without fully understanding before I read this excellent new translation, that the idea of death in this novel is peculiarly pinned to the idea of execution — what I had not thought through was that in a materialist world the dead man in the painting is an executed man, whose consciousness has been brutally cut off. There is a rhythmic meditation on murder and execution in this story, at its most powerful and unbearable when Myshkin makes us confront the horror of the certainty of being about to die, of knowing that it is exactly appointed and inevitable, while the body and mind are in ordinary good health. The appalling nature of the close examination of these unimaginable emotions derives from the authority with which Dostoevsky can describe them, since he was himself condemned to death and reprieved, by an imperial whim, or display of power, as he stood in line at the scaffold behind a friend who had indeed just been killed. The novel describes the execution by guillotine of a French murderer. The unholy fool, the talkative Lebedev, takes it into his head to pray for Madame du Barry, elegant and witty, asking for another moment with the executioner's foot on her neck. Connected to the certainty of execution is the plight of the consumptive boy, Ippolit, staring out at a blank wall, trying to make a gesture of his death (he bungles his suicide) with a paper pathetically entitled " Après moi le Déluge ". Rogozhin is not executed but transported to Siberia for his murder of Nastasya Filippovna. The prince recedes into blank idiocy after watching with the killer over the corpse. Connected to the terrible lucidity of the condemned man in the tumbril is the unearthly lucidity of the pre-epileptic aura, bliss without time or space, eternity in an instant. The images are their own meaning.Part of the problem of the plot of The Idiot is that most of the other characters appear insubstantial, and the women's capriciousness leads to a series of wild and inconclusive gestures to which it is hard to react. Much - not all - of this is to do with the problem I mentioned earlier, of the awkward relation between sexual energy and goodness. The women think they are in a story about seduction, rape, proposals, money and marriage, like most novels in the realm of the passions and economic forces. The prince is in some absolute moral world in which he can instinctively gauge who is being cruel to whom, who is in need and who is tormenting or tormented, without having in him any genuine sexual response of his own to help him to judge his own effect on people. It is the old problem of "How could Jesus be a perfect man if he had no sexual desire or experience?" There is considerable psychological subtlety in the moment-to-moment actions and reactions of Nastasya Filippovna and Aglaya, who both consider "loving" the prince for those qualities of patience and attention and kindness, which do attract both over-experienced and gawkily innocent women. Both are also, I think, repelled without knowing it by something abstract in the prince's practical virtue, which appears alternately as a deficiency of some kind, and as an alarming right to judge impartially. He isn't really in their world, and neither they nor he quite understands this.

He does resemble his comic models, Don Quixote and Mr Pickwick, in that his innocence causes damage. Quixote inhabits the first real novel, in which the old forms of romance and religion become phantasms in his head and on our page, present but shadowy. Myshkin is a later, more riddling and more tragic figure of lost absolutes. In a world where God is simply dead flesh, a good man becomes simply an idiot.

AS Byatt's The Little Black Book of Stories is published by Chatto & Windus.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/jun/26/highereducation.classics

=====================

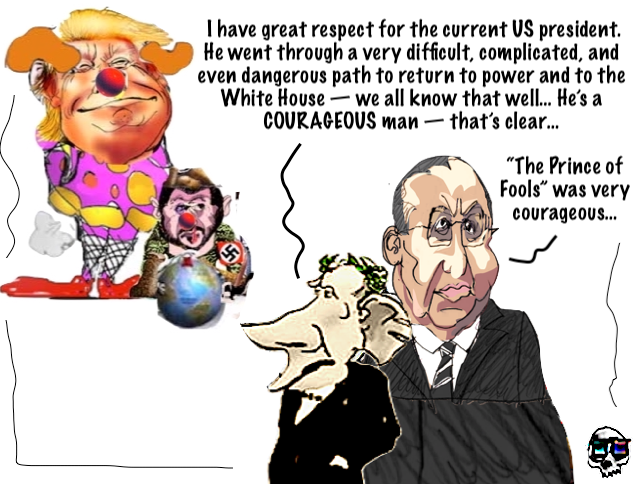

Russian President Vladimir Putin said he has “great respect” for US President Donald Trump and praised his counterpart’s efforts to resolve the Ukraine conflict.

Speaking to reporters in Minsk on Friday after a meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, Putin described Trump as “a courageous man,” who had overcome serious challenges to return to the White House, including surviving multiple assassination attempts.

“I have great respect for the current US president. He went through a very difficult, complicated, and even dangerous path to return to power and to the White House – we all know that well… He’s a courageous man – that’s clear,” Putin said.

He also commended Trump’s diplomacy in the Middle East, as well as his efforts to resolve the Ukraine crisis. “We, of course, value all of that… I believe President Trump is sincerely striving to resolve” the conflict.

He expressed appreciation for Trump’s domestic and foreign policy initiatives, particularly highlighting his steps in the Middle East and “sincere commitment” to resolving the Ukrainian conflict.

Putin said Trump’s recent admission that dealing with the situation was tougher than he had expected came as no surprise. “It’s one thing to observe from the sidelines and quite another to dive into the problem.”

Asked whether it was time for a face-to-face meeting, Putin said, “I am always open to contact, to meetings… and we would be happy to work on making that happen.” He observed that Trump had also expressed interest, while noting that both leaders believed such meetings should be properly prepared and lead to tangible progress in cooperation.

“Thanks to President Trump, relations between Russia and the US are beginning to level out, at least to some extent. Not everything has been resolved in terms of diplomatic relations, but the first steps have been taken, and we are moving forward,” he added.

Since returning to office in January, Trump has worked to rebuild ties with Moscow, which were largely severed under his predecessor, Joe Biden. Trump and Putin have had multiple phone conversations concerning the Ukraine conflict and broader bilateral issues.

The diplomatic push helped reboot direct negotiations between Russia and Ukraine, which Kiev had abandoned back in 2022, reportedly at the behest of its Western backers.

The latest round in Istanbul earlier this month resulted in the largest prisoner exchange to date, as well as a pledge to continue dialogue.

Trump said this week that he would like to see an agreement with Russia that ends the hostilities.

Moscow has consistently reaffirmed its commitment to achieving a diplomatic resolution. Putin has said that Russia is ready to work with Kiev on drafting the document and emphasized that “eliminating the root causes” of the conflict “is what matters most to us.”

https://www.rt.com/news/620673-putin-trump-ukraine-conflict/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 28 Jun 2025 - 7:57am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

warmonger....

Trump’s ‘Antiwar’ Myth and the Zionist Reality

JOSE ALBERTO NINO

Donald Trump’s “America First” message promised an end to foreign entanglements, but his aggressive Iran policy tells us a different story. His administration’s decision to carry out airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities in Isfahan, Fordow, and Natanz on June 21, 2025 further underscores this contradiction. But when one looks at his overall track record, one realizes that Trump has been a consummate Iran hawk from day one.

Trump’s claim to be an antiwar president has been a cornerstone of his political brand since he first entered the national stage. He has repeatedly declared, “Great nations do not fight endless wars.” On the campaign trail, he positioned himself as the candidate who would break with the interventionist consensus of the past, railing against the Iraq War and the “forever wars” of his predecessors. In his 2019 State of the Union, he told Congress and the nation, “Our brave troops have now been fighting in the Middle East for almost nineteen years…It is time to give our brave warriors in Syria a warm welcome home.”

Even in his second campaign, Trump doubled down: “I’m not going to start wars, I’m going to stop wars.” But this antiwar rhetoric has always been a smokescreen, especially when it comes to Iran—a country that has been the singular focus of Trump’s most aggressive, interventionist actions.

Trump’s hostility toward Iran’s alleged nuclear ambitions is well-documented. He made his opposition to Iran’s nuclear program clear long before his 2016 campaign. In his 2011 book, Time to Get Tough, Trump wrote:

“America’s primary goal with Iran must be to destroy its nuclear ambitions. Let me put them as plainly as I know how: Iran’s nuclear program must be stopped–by any and all means necessary. Period. We cannot allow this radical regime to acquire a nuclear weapon that they will either use or hand off to terrorists.”

Throughout 2015 and into 2016, Trump consistently criticized the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal. He described it as “a disaster,” and so “terrible” that it could lead to “a nuclear holocaust,” during his first presidential campaign.

While Trump talked peace to certain political audiences, his actual policy toward Iran was one of relentless escalation. The “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign, launched after his unilateral withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, marked a sharp break from his antiwar persona. Trump called the Iran nuclear deal “the worst deal ever,” claiming it “enriched the Iranian regime and enabled its malign behavior, while at best delaying its ability to pursue nuclear weapons.” He ordered the immediate reimposition of sanctions, targeting Iran’s energy, petrochemical, and financial sectors, and promised “severe consequences” for anyone who failed to shut down business ties with Iran.

These sanctions were among the harshest in modern history, designed to “bring Iran’s oil exports to zero, denying the regime its principal source of revenue.” Trump’s administration continued to add new layers of sanctions, targeting Iran’s central bank, space program, and even the Supreme Leader’s inner circle. In October 2019, Trump sanctioned the Iranian construction sector, explicitly linking it to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which he had just designated as a foreign terrorist organization—the first time the United States had ever labeled another nation’s military as such.

Trump boasted, “If you are doing business with the IRGC, you will be bankrolling terrorism…This designation will be the first time that the United States has ever named a part of another government as an FTO [foreign terrorist organization].” These moves were not just economic warfare, they were also designed to isolate Iran diplomatically, cripple its economy, and lay the groundwork for military escalation.

The most dramatic example of Trump’s hawkishness in his first term was the January 2020 assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, ordered by Trump via drone strike in Baghdad. Trump justified the strike by claiming Soleimani was “plotting imminent and sinister attacks on American diplomats and military personnel,” but the move brought the United States and Iran to the brink of open war. Iran responded with missile strikes on U.S. bases, and the world held its breath as both sides teetered on the edge of a wider conflict.

Even after this near-miss, Trump continued to escalate. In the final months of his first term, he reportedly sought options for military strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities. It was only the intervention of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley and other senior advisers that prevented Trump from moving forward. Milley warned, “If you do this, you’re gonna have a f***ing war,” and implemented daily calls with top officials to “land the plane” and avoid a catastrophic conflict.

Trump’s second term has seen a return to this pattern. In 2025, he resurrected the “maximum pressure” campaign, signing a memorandum to reimpose and expand sanctions on Iran, targeting its nuclear program and broader economy.

As tensions with Iran and Israel escalated, Trump privately approved plans for U.S. military strikes on Iran, moving carrier strike groups, bombers, and advanced fighters into position for a potential attack. Trump informed senior aides that he “approved of attack plans for Iran, but was holding off on giving the final order to see if Tehran will abandon its nuclear program,” according to The Wall Street Journal.

This is not the behavior of an antiwar president; it is the playbook of a hawk. As the current crisis with Iran and Israel threatens to spiral into a wider war, Trump’s true priorities are clearer than ever. According to a report by The Independent, Trump has been “increasingly shunning the isolationist advisers he brought into his cabinet—and those who helped get him elected to a second term—in favor of a trio of hawkish voices who’ve spent years arguing for the United States to take action against Iran.”

While he tells the public, “Nobody knows what I’m going to do,” the reality is that his administration is preparing for war, moving military assets into place and seeking counsel from the most hardline Iran hawks in Washington.

To his credit, President Trump broke his silence following Iran’s missile strike on a U.S. base in Qatar on June 23, 2025, signaling that he does not intend to retaliate. In a series of Truth Social posts, he downplayed the attack, calling it “a very weak response” and portraying it as a step toward de-escalation. In one all-caps message, he declared, “CONGRATULATIONS WORLD, IT’S TIME FOR PEACE!” However, it’s too soon to start labeling Trump as a peacemaker in this respect. Israel is still carrying out strikes in Iran, and there’s reason to believe that Israel’s escalations since the middle of June are just the first act of a broader regime change campaign.

Overall, the lesson here is simple: do not be fooled by empty rhetoric. Trump’s antiwar messaging is designed to win votes, not to guide policy. The real story is told by his actions, his appointments, and his donors. Trump put on the antiwar costume because he correctly recognized that there’s a large constituency in the electorate that’s tired of perpetual warfare. The pro-Israel lobby has spent over $230 million supporting Trump since 2020, and his cabinet is stacked with figures who see Israeli interests and U.S. military intervention as inseparable such as Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth.

In the end, Trump’s Iran policy is not an exception to his antiwar brand—it is the reality behind the illusion. His presidency has been a smokescreen for a pro-Zionist, hawkish agenda that has brought the United States and the Middle East closer to war, not peace. The next time a politician promises to end “endless wars,” look past the slogans.

Follow the money. Examine who leaders appoint. And judge them by what they do—not what they say.

https://libertarianinstitute.org/articles/trumps-antiwar-myth-and-the-zionist-reality/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.