Search

Recent comments

- success....

1 hour 13 min ago - seriously....

3 hours 57 min ago - monsters.....

4 hours 4 min ago - people for the people....

4 hours 40 min ago - abusing kids.....

6 hours 13 min ago - brainwashed tim....

10 hours 33 min ago - embezzlers.....

10 hours 39 min ago - epstein connect....

10 hours 51 min ago - 腐敗....

11 hours 10 min ago - multicultural....

11 hours 16 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the industry of "culture"....

In recent years, cultural productions have often been criticised for ideological reasons in opposition to "wokeism," whether national or international. A form of "wokeism" paranoia has mingled with another, much more concrete sentiment: a strange nostalgia.

La production industrielle des biens culturels

par Arcture

In a spontaneous movement, the "things were better before" strangely resurfaces, notably through the fantasy of bygone eras. This is obviously a reaction we must combat because it prevents any clarification and understanding of the situation. A situation that encourages inaction and complicates its overcoming. For example, how can Marvel produce so many films? Why does Disney readapt and reinterpret its own classics? Why does so much music sound so similar? Why do so many video games reuse Japanese aesthetics? Etc. Without providing an exhaustive list of all the difficulties currently facing mainstream culture, all these questions have one common characteristic: the cultural goods industry. So, what are the reasons for the decline of this industry, what are the origins of this feeling of nostalgia?

All the arts and productions we have discussed are the result of an industrial production process, that is, the planning and distribution of tasks among several people. Industry was initially considered to be the transformation of materials, but the definition broadened with the development of capitalism and the expansion of its mode of production. Let us first observe the historical link that was created between art and industry. We can then move to our own time and draw conclusions based on our analysis of the historical evolution of the production of cultural goods.

The history of art, and of culture, tends to neglect the popular culture of the masses to focus on the cultural production of the elite, which is much more persistent over time. This phenomenon can be explained by the cognitive bias inherent in scientific research, which requires traceability, a testimony of the object studied. Popular culture, through its use of poorer materials (when it comes to sculpture or painting) as well as its oral transmission, has only limited longevity and traceability in history. Thus, with the emergence of schools and the humanities, orally transmitted popular culture and the aristocratic and bourgeois culture of schools were able to coexist for a time. Understand by this the phenomenon of the transmission of songs, tales and legends or popular representations through the spontaneity of daily and oral interactions among the masses. A continuous transmission and creation that took place within the home, in the community, or even in the workplace. These cultural phenomena evolve singularly throughout history, without us being able to observe them. Let's take the Breton myth of Ankou, the personification of death. This myth is very present in Brittany. Despite its polytheistic origins, Ankou is a figure who, thanks to oral transmission, has been able to survive the changes in Catholicism and Breton society. The myth is so present and rooted in this territory that it appears on the facades of certain Breton churches. However, it is difficult to know why this myth has persisted rather than others, and the conditions that allowed its continued transmission. Things are simply that way.

However, the emergence of industry brought about a radical shift in the paradigm of the masses. Populations left the countryside to find work in the cities with the rural exodus of the industrial era. However, these countrysides were the historical centres of popular culture. A new culture replaced it: that of the urban working population. The capitalism of this era was then in a phase of expansion. It acquires and seizes new fields. Scientific advances and the rapid creation of capital push towards rapid industrialisation of all material goods production. However, this development over a few decades has undermined the competition cherished by 18th-century liberals, and the concentration of different sectors has become increasingly intense. Competition is gradually destroyed, resulting in a concentration of different sectors in the hands of a few industrialists. The rate of profit is then reduced because capital can no longer be reinvested. Industrialists must then find a way to circumvent this inevitable decline.

A simple solution was the expansion of capital through the creation of new markets. Thus, the money that no longer circulated and stagnated in the hands of these few industrialists could be reinjected into new competition through market expansion. This process occurs by opening up a sector that was still closed to investment, or by creating a new economic sector, as was the case with oil, automobiles, computers, the internet, and so on. It was in this transitional context of the 19th and 20th centuries that radio, photography, and cinema emerged. These were new industrial sectors, born of technological development and therefore open to industry. These new media found a resounding response among the masses, particularly cinema. A new form of industry took shape: the cultural industry.

These new markets had a dual advantage: they were profitable and ensured the conditions for the reproduction of capital thanks to the propaganda they provided for capitalist ideology. Far more powerful than newspapers or paternalistic corporate management, cinema and radio, through their creation of entertainment but also through the ability to permanently insert bourgeois ideology, were quickly understood as genuine propaganda tools. However, these cultural productions failed to establish themselves as a total replacement for popular and aristocratic culture (i.e., bourgeois art, heir to the art of the church and the nobility). The different cultural systems thus coexisted for a time, each unable to replace the others.

However, this industry remained subject to the laws of capitalist profitability. Once the new market opened up at the beginning of the 20th century, the various players competed in a competitive manner until some grew large enough to be able to buy out the others. A status quo was established among the last survivors of the market distribution. Competition, which should have continually forced manufacturers to improve their production and merchandise, no longer exists; only the continuity of profit prevails. This is how production becomes structured and standardised. This phenomenon of the industrialisation of culture, in the middle of the last century, was theorised by Adorno in his book Dialectic of Reason, published in 1947 and co-written with Horkheimer. The two leaders of the Frankfurt School developed their thinking in what they called advanced capitalism, which corresponded to the economic development of the time. Thus, we can read in their work:

"In advanced capitalism, amusement is an extension of work. It is sought by those who wish to escape the automated labor process in order to be able to confront it again.

Capital, by structuring itself during its expansion, resolves some of its contradictions in order to maintain itself. Since the 19th century, worker productivity has only increased. But this increase in productivity necessarily implies a human cost and daily difficulties. The cultural goods industry will then provide a means to divert and reassure workers, without which they would be unable to cope with their alienation at work. Amusement, games, and entertainment become tools against workers in the hands of industrialists. The alienation of work is safeguarded by the alienation of culture.

Furthermore, as we have said, capitalism spontaneously creates monopolies. The monopolistic path is the common path for all capitalist enterprises. Thus, the popular culture of the masses competes with the cultural goods industry. However, the creation of artistic works for the masses requires a certain economic freedom to allow the public expression of popular feelings. Competition with the productive and structuring power of the cultural industry is impossible.

"But what is new is that the irreconcilable elements of culture, art and entertainment, are subordinated to a single end and thus reduced to a single formula which is false: the totality of the cultural industry."

As industry grows stronger, resistance becomes increasingly difficult. It creates identical, easily assimilated, and simplistic products in far too large a quantity for popular production to compete with. The latter gradually disappears. However, this is not just a replacement, but an impoverishment. The productions of the cultural industry have simplistic structures, they focus on conservative ideals with infantile morality, and are cloaked in fascinating spectacle. Everything is then reproduced at high speed by industrial organisation.

My point is global; I address all these industries of books, television, film, radio, and, more recently, video games. The people are prevented from creating by work, the destruction of social and urban structures, and the monopoly of various industries. But that's not all; aristocratic culture is also degraded, transformed to resemble the rest, then served in a stupefying form. Take the myth of Hercules, adapted into a musical cartoon by Disney in 1997. In the original myth, Hercules is the result of yet another deception by Zeus. Hera, in revenge, tortures Hercules throughout his life, subjecting him to terrible ordeals and forcing him to kill his wife and children in a murderous frenzy. Disney completely changed the myth to make it coincide with its entire production, but also with its ideology. Hercules becomes the result of the legitimate union between Zeus and Hera, captured by Hades (god of death), who covets his brother's place as king of the gods. Hercules is presented as a simple-minded young adult, who will put an end to Hades' "diabolical" plan to upset the established order. The success of his quest allows him to be reunited with his parents and reform the family union. The film is therefore a childlike hero's journey, from which all the tragic substance has been removed. The myth is destroyed and reinterpreted to become conservative Protestant propaganda.

Culture is stolen from the people, only to be returned in a reduced and simplistic form. As industry develops, it increasingly takes over popular culture, which is no longer produced by the people, but produced by a few industrialists for the people.

However, we are in a very advanced stage of capitalism, with an immense concentration of capital, as evidenced by the multiple acquisitions carried out in recent years, for example, by Microsoft and Disney for tens of billions. Capitalism seeks profitability; that's why it invests in new markets and develops new products. But once a monopoly is acquired, investment disappears in favour of maximising profitability. Novelty disappears in favour of sclerotic stagnation. Products no longer evolve, and research and development are sidelined. Products are slightly modified, just enough to sell, but enough to avoid requiring production costs. Invested capital is squeezed to the maximum of its production and profitability capacity. Everything is then standardised and regulated to be produced at the lowest cost, for maximum profitability. What was copied continues to be copied, with a gradual decline in investment, but always at the same production rate. Cultural objects resemble each other, production continues to continually overwhelm us, but the "quality" has disappeared, making a dish that had no taste even more bland.

The implantation of ideological elements and criticisms of "wokeism" have always been present in industrial production because it makes it easier to sell the former, like a wink to people sensitive to the ideology described, but also because it serves the dictatorship of capital. The feeling of nostalgia that has been mixed with all this is a true popular tragedy. The masses, dispossessed of all cultural production, come to miss the past productions of industry, from a time when it still cared about producing a semblance of quality. The real problem lies in this industrial form of cultural goods production, not in its ideological shifts or the degradation of its production, which was, in any case, inevitable by the same laws that allowed it to prevail.

Arcture

https://www.legrandsoir.info/la-production-industrielle-des-biens-culturels.html

TRANSLATION BY JULES LETAMBOUR.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

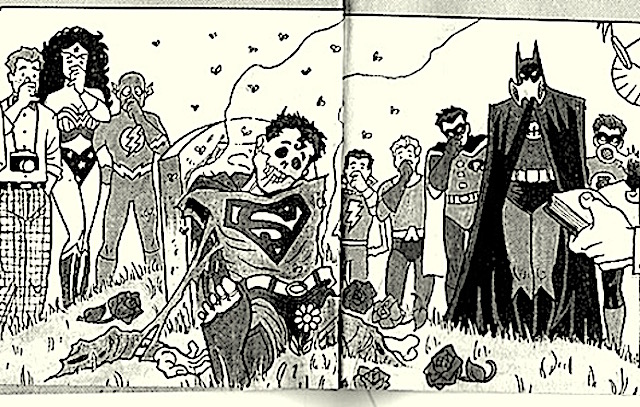

TOON AT TOP FROM MAD MAGAZINE C.1970s

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Aug 2025 - 12:34pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

arcture....

Nous, Jeunes pour la Renaissance Communiste en France (JRCF), constituons l’organisation de jeunesse du PRCF (Pôle de Renaissance Communiste en France). Comme nos aînés, nous refusons la mutation sociale-démocrate et “€uroconstructive” de ce qui était, à la Libération, le grand parti de la classe ouvrière. Nous tendons la main, dans l’action, aux militants franchement communistes du PCF et aux jeunes communistes du MJCF, qui refusent la liquidation de leur parti.

Comme organization de jeunesse, il nous revient la tâche d’être à l’avant-garde du combat communiste que porte notre organization. Notre nom est notre programme. Comme avant-garde, sachant, selon le mot de Lénine, se tenir "un pas [et un seul] au-devant des masses", nous nous devons de rester au plus près de notre classe, de lui apporter notre fougue indéfectible et notre soutien fraternel, dans ses luttes présentes et à venir. Nous sommes à l'avant-poste, fiers de ce que nous portons, audacieux et combatifs.

Exigeants avec nous-mêmes, fraternels avec nos camarades, intransigeants avec nos adversaires, nous posons d'ores et déjà les jalons de la cité future que nous voulons et que nous allons bâtir.

https://jrcf.fr/qui-sommes-nous/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

NZ on Air....

NZ on Air is confronting a very uncomfortable question: what to save, and what to leave behind.

Duncan Greive

Funding announcements from NZ on Air are not typically newsworthy in and of themselves. The agency functions as a local version of the BBC, but instead of existing as a non-commercial umbrella brand, it funds a variety of media which runs across a wide range of largely commercial mediums and platforms. Funded work often consists of a mix of returning shows and new projects, which are either predictable (another season of Q+A, or a fresh David Lomas project) or largely unknown (another murder in rural New Zealand, cast tbc).

The most recent round was strikingly different, making news in a way which reveals challenges to the agency’s model, and shows just how bad the choices are for NZ on Air now. Three very familiar shows collectively received more than $5m in funding. They are Shortland Street, Celebrity Treasure Island and The Traitors NZ. All are broad in their appeal and comparatively popular. Yet none would have been considered good candidates for funding until very recently.

That’s because NZ on Air was set up to address a market failure. Due to our small population, some forms of “programming reflecting New Zealand identity and culture” (according to its legislation) are not commercially viable. The legislation makes specific reference to “drama and documentary”, with everything else somewhat in the eye of the beholder.

For decades that meant scripted shows (such as comedy and drama) were NZ on Air’s core business, while most other formats (from current affairs to breakfast TV) were commercially funded, due to TV networks being able to sell enough ads to make them on their own terms. That didn’t mean it lacked value, just that it didn’t need the support. News is the canonical example of a commercially funded genre – TVNZ’s 6pm bulletin remains among the highest-rated shows on television, despite costing a bomb to make.

Reality TV wasn’t even a genre when NZ on Air was founded, and the agency has tended to be fairly circumspect in its funding of it over the years, only getting involved when, as with Match Fit, or Popstars, it fulfilled another worthy goal. Shortland Street, our only true soap, was briefly funded as a kind of TV startup, but cranked along under its own steam for decades afterwards. This was helpful because reality TV and soaps are considered less intellectually nutritious by the kind of people who care about the culture we fund.

The end of that era

This has not been an uncontested idea. Critics, including those at The Spinoff, and the makers of reality TV have long felt that NZ on Air was too prescriptive in its definition of “reflecting New Zealand identity and culture”. They believe that reality TV and soaps are popular, show a diverse range of New Zealanders and bring voices, vernacular and perspectives to our screens, just as scripted comedy and drama do.

This past week, they won the argument. Shortland Street has returned for a second funded season, after last year accessing two different strands of public funding to stay on air. More striking was the return of The Traitors NZ and Celebrity Treasure Island, two shows which had previously been commercially funded. Celebrity Treasure Island is a revival of an ‘00s-era format, and has drawn praise for its use of Te Reo Māori and addressing “complex issues like ageism, sexism and queer politics, all on primetime mainstream television”, according to my colleague Tara Ward. The Traitors NZ is a hit local version of a smash international format, with a diverse cast and a strong strain of New Zealand-specific humour.

In addition to the cultural arguments, there’s also a broader systems-level case for their funding. The shows have consistently rated strongly, particularly with the kind of middle-aged audiences which have abandoned linear television over the past decade. The thinking goes that by keeping these tentpole shows on our screens, you also help keep our networks and production companies viable.

The path not taken

Despite the solid arguments in favour, there remains a case against, too. To contemplate it, you only need to cast your mind back to a little over a year ago. It was a bonfire of the journalists. We lost longform current affairs stalwart Sunday, the venerable consumer rights show Fair Go, the magazine-style 7pm staple The Project and, most wrenchingly, the whole Newshub operation, all in the space of a few harrowing months.

The death of those shows was attributed to the awful financial equation facing TV networks. That despite all rating very strongly, at least by comparison to the rest of the schedule, none could justify the investment required to keep them running. It was a shocking, visceral event, one which made New Zealand a cautionary tale across the Tasman – the country you need to look hard at to figure out how to avoid its fate.

Now, a year on, and NZ on Air has been persuaded by the arguments of TVNZ and Three, that these reality TV and soap formats are too important to be allowed to die. To be clear, none of Shortland Street, Celebrity Treasure Island or The Traitors NZ is fully funded. The budgets aren’t public, but production industry sources suggest the agency’s investment would cover no more than 50% of the associated costs, and perhaps considerably less.

Still, the risk of moral hazard is clear. The networks and production companies have established that no show is beyond help, and as audiences decline, there is a manifest case for continually topping up the public funding component of budgets. The implication is that paradoxically, as they get less popular and ad revenue declines, they should receive more help.

None of which is to say these decisions are wrong in isolation. But looking at the slate of what we publicly fund now, we seem a long way from home. Pulpy true crime documentaries, reality TV shows with large chunks devoted to selling McDonalds, regularly re-named shows built around the interests of a single comedian.

Still, what else can we do? Linear TV audience decline is a global phenomenon, and no public or private broadcaster has successfully ported their audiences across to digital at the same scale as they once had, let alone been able to defend the same advertising revenues. NZ on Air faces bad choices everywhere as it seeks to fulfil its mission and defend its model. It may not have even been given the chance to save the news.

But as we slip gently into a new era, where everything which can be argued can be funded, it’s important to remember the shows we didn’t save too. And ask whether the foundational mission of NZ on Air is better served by what we kept, or what we threw away.

https://thespinoff.co.nz/pop-culture/05-08-2025/nzoa-has-saved-reality-tv-and-soaps-what-about-all-the-shows-left-to-die

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.