Search

Recent comments

- seriously....

2 hours 24 min ago - monsters.....

2 hours 32 min ago - people for the people....

3 hours 8 min ago - abusing kids.....

4 hours 41 min ago - brainwashed tim....

9 hours 1 min ago - embezzlers.....

9 hours 7 min ago - epstein connect....

9 hours 19 min ago - 腐敗....

9 hours 38 min ago - multicultural....

9 hours 44 min ago - figurehead....

12 hours 53 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

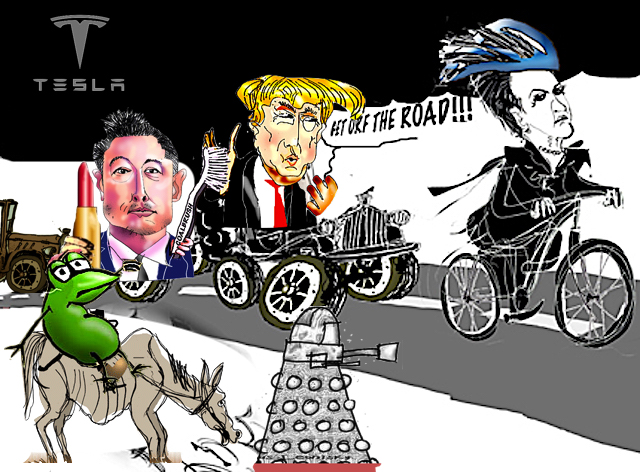

"smoking kills — for short journeys, walk or cycle".....

The transportation sector is poised to claim the top spot as the European Union's largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting sector. Electric cars are among the tools in the fight against global warming. They emit less than their internal combustion cousins, but are not "zero emissions" or "zero environmental impact." Their use contributes to a carbon bill already burdened by their manufacturing, particularly their battery, which accounts for half of the total. The emission level indicator is linked to that of the country's electricity mix. We'll explain everything!

Electric Cars: The Illusion of an Ecological Miracle

BY ELUCID

During the summer, Élucid invites you to (re)discover some of our fundamental graphic analyses on various essential and still topical topics (original publication date: October 28, 2024).

The expected mass adoption of electric cars, which are resource-intensive, suggests competition for materials, not to mention the issue of the acceptability of mines and the associated pollution. This acceptability is very fragile in Europe, such as in Serbia and France, where anger is brewing and often leads to having to source—and therefore pollute—elsewhere.

Betting everything on electric cars alone to achieve the target of decarbonizing transport and sustainable development will not be enough. It must be accompanied by proactive policies that, rather than shifting the responsibility onto citizens' shoulders, provide them with better access to public transport or facilitate soft mobility (walking, cycling, etc.)... otherwise, not only will you lose your investment, but you will also miss the climate target.

Transport, the second largest GHG emitting sector, is inexorably eating into the carbon budget.

Transport, excluding aviation and maritime transport, is responsible for one-fifth of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. They are on an upward trend despite regular reminders from scientists about the need to reduce emissions to avoid climate catastrophe. Until 2022, transport held second place on the podium of emitting sectors within the European Union, behind electricity and heat production, but it took first place in 2023... a position it already held in France, where it is responsible for 32% of annual emissions, far ahead of other sectors (electricity and heat represent less than 10% of the total).

And the IPCC drives the point home: "without intervention, CO2 emissions from transport could increase by 16% to 50% by 2050", the consequence of continued growth in demand for freight and passenger transport services, particularly in Africa and Asia.

The carbon budget, or residual carbon budget, "refers to the total net quantity of carbon dioxide (CO2) that can still be emitted by human activities while limiting global warming to a specified level." It is an emissions quota with no expiration date on a human scale, meaning that any excess automatically triggers further global warming, until it returns to within the permitted emissions quota (1). Without government intervention, transportation is currently on track to significantly dent the carbon budgets for +1.5°C and +2°C.

Thus, the carbon budget to limit global warming to +1.5°C is only 275 billion tonnes of CO2 as of the beginning of 2024. At the rate of 2023 emissions, this budget will be used up in just seven years. Without this guaranteeing the achievement of climate objectives...

The budgets to have a slightly better chance than a coin toss of staying below +1.5°C are even smaller, and they will be exhausted within the next four to five years. To stay below +2°C, the budget of 1,150 billion tons of CO2 will be exhausted by 2050, at current emission levels. These carbon budgets are subject to significant uncertainties regarding their actual levels, and they also assume that the planet will be "net zero" upon their exhaustion, meaning that residual emissions will be completely absorbed by natural and technological carbon sinks.

In terms of climate, we are collectively acting like grasshoppers... at the risk of finding ourselves severely deprived once our carbon budgets are consumed and the climate is disrupted…

Given its contribution to emissions, the IPCC concludes that "achieving climate change mitigation targets would require a transformation of the transport sector." According to their assessment, this drastic transformation is required to achieve a 60% to 70% reduction in the sector's CO2 emissions by 2050.

As a former Prime Minister would say, "our road is straight, but the slope is steep."

The electric vehicle, the flagship of transport decarbonization

Passenger cars and light commercial vehicles account for half of transport emissions. To reduce the bill, the IPCC suggests activating two levers simultaneously. First, reducing demand for transport and "promoting the shift to more energy-efficient modes of transport." Second, developing low-GHG emission technologies, particularly electric vehicles powered by low-emission electricity.

With the decarbonization of electricity, electric cars have a clear advantage over internal combustion engines in terms of GHG emissions over their entire lifetime (manufacturing, use, and recycling). However, although less energy-intensive, they are not "zero emissions."

The manufacture of a car requires minerals that must be extracted from the ground (iron, copper, nickel, etc.), then transformed through industrial processes into body parts, running gear, engines, electronic components, etc., or even plastics derived from hydrocarbons (interior trim, etc.). Manufacturing the battery is roughly as energy-intensive as manufacturing the rest of the car, and ultimately, the production of an electric car produces twice as many emissions as that of an equivalent internal combustion model. This surplus is called the "carbon debt."

Countries' electricity mixes determine the absolute value of emissions during manufacturing, but also during use. The less GHG the mix emits – due to the use of electricity from renewables or nuclear power – the lower the emissions recorded per kilometer traveled will be.

Electricity mixes vary from country to country, and therefore, the final total GHG emissions from electric vehicles vary. In this respect, France stands out thanks to the predominance of its nuclear fleet in its electricity production. With emissions estimated at ~6 g CO2e/kWh, French nuclear power plants are 150 times less polluting than coal-fired power plants.

There is a direct correlation between the growth of low-carbon energy sources and the reduction of vehicle emissions. If countries meet their commitments, manufacturing emissions are projected to decrease by 20% to 25% for internal combustion vehicles and by around 10% for electric vehicles by 2030. This trend is reinforced by the implementation of new, lower-emitting technologies and the development of recycling (batteries, materials, etc.).

Ultimately, despite the "carbon debt" of manufacturing, electric vehicles are less polluting regardless of the country of use (1, 2) and generally reduce emissions. In countries with the lowest-carbon electricity mix (France, Sweden, and Finland), the carbon footprint of electric vehicles over their entire lifespan is three times lower than that of a combustion engine model; it's half as low in Germany or Italy. This observation remains valid in countries where electricity production is much more GHG-intensive, such as Estonia, Poland, and Cyprus. An electric vehicle is on average responsible for a third fewer GHG emissions than a combustion engine.

Across the European Union, an electric car has thus repaid its "carbon debt" after one or two years of use and avoids the emission of approximately 30 tons of CO₂ over its entire lifespan compared to an equivalent combustion engine. Snowball effect: the higher the mileage covered by an electric car, the more advantageous it becomes compared to a thermal vehicle.

These conclusions are extended to all countries by Rystad Energy, an independent energy research and intelligence firm: "Overall, the adoption of electric vehicles—even in the case of a future electricity mix at the status quo—will be beneficial for the environment, particularly in countries with high annual mileage, such as the United States."

For example, China, where 60% of its electricity comes from high-carbon coal-fired power plants, will emit 230 million fewer tons of CO2e over the lifecycle of the more than 5 million electric vehicles sold in 2022. This represents a reduction of almost 15% in emissions from the Chinese vehicle fleet, equivalent to two-thirds of France's total emissions in 2023. In France, 7 million tons of CO2e are expected to be avoided thanks to the sales of 200,000 electric cars in 2022.

Electric cars are insufficient to reverse the downward spiral of climate change

With the contribution of developing countries, particularly China, India, and other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, the global passenger car fleet is set to increase. As their economies develop, inexpensive and environmentally efficient modes of transportation, such as two- and three-wheeled vehicles, buses, and rail, are gradually being replaced by the more practical, but much more energy- and material-intensive, private car. All this in countries that often have a carbon-intensive electricity mix.

The International Energy Outlook 2023 report from the U.S. government agency EIA (Energy Information Administration) explores long-term global energy trends through 2050. Its projections estimate that the global light-duty vehicle fleet, over 90% passenger cars, will grow from 1.4 billion in 2022 to over 2 billion units by 2050. Electric vehicles will gradually gain market share until they account for between 30% and 50% of global new vehicle sales.

Ultimately, however, and given current public policies, we will still be a long way from completely replacing combustion-engine vehicles: there are still expected to be over a billion of them on the road worldwide. Due to the incentive policies implemented and the size of their respective markets, China and Western Europe will capture the lion's share of the 650 million to 900 million electric cars that will then be on the road.

The independent research organization ICCT, the International Council on Clean Transportation, has assessed the consequences of projected global vehicle fleet composition and size for 2050. Under current regulations and without increased decarbonization efforts, road transport emissions (passengers and freight) between 2020 and 2050 would represent 285 billion tons of CO2. This represents an excess of more than 240% of the 84 billion tons of CO2 allocated to transport to limit global warming to +1.5°C. Even the +2°C target (210 billion tons of CO2) is compromised, with the carbon budget exceeding this by more than a third.

The primary issue is the number of vehicles on the road. With 1.5 to 2 billion cars on the road, any deviation from "zero emissions" assumes gigantic proportions. If the global vehicle fleet were to switch to all-electric tomorrow, with a particularly virtuous electricity mix like France's, that would still be around 1 tonne of CO2 emitted each year per vehicle. Over the 27 years between now and 2050, that's around 50 billion tonnes of CO2 emitted, or 85% of the residual +1.5°C carbon budget for 2024 for all road transport (passengers and goods). And we would have to start today, with no guarantee of staying below +1.5°C!

Electric Cars: A Reduced Environmental Footprint, But Still Too Large

Today, in a world dominated by fossil fuels, gargantuan quantities of materials are extracted from the ground each year. Between 2018 and 2022, 12.5 billion tons of raw coal (coal plus waste) were extracted annually; for oil and gas, it's more than 8 billion tons annually. These are fossil fuels intended to be burned to produce electricity and industrial heat.

In total, 50 billion tons of rocks, metals, and fossil fuels are extracted each year for the entire manufacturing and operating chain of transportation and electricity generation. These two sectors alone are reaching, or even exceeding, the sustainable limit of natural resource use at the global level, estimated at between 25 and 50 billion tons per year.

The transition from a fossil-fueled world to an electric one will result in a decrease in demand for fossil fuels and an increase in demand for metals. The IEA anticipates a six-times higher demand for ore for electric vehicles than for combustion engines. For electricity production, for example, a wind power plant requires nine times more ore than a gas-fired power plant.

Overall, demand for metals will explode (sevenfold by 2050), driven by iron, copper, nickel, silver, tellurium, cobalt, and lithium, used in the production of photovoltaic solar panels and electric vehicles.

The simultaneous reduction of a factor of four in fuel extraction results in an expected reduction in the extraction of natural resources of one-third compared to the current situation in the areas of transport and electricity production. This is especially true since it involves replacing resources that are consumed as they are extracted (fossil fuels) with resources that can be stored and reused through recycling (metals).

Electrification, particularly of transportation, certainly reduces the overall demand for natural resources, but the environmental footprint remains very significant. The combined effect of increased demand and low mineral content in the soil implies that significant quantities of raw minerals will be extracted (around 20 billion tons for metals).

The risks of mineral shortages are, however, low according to researchers; it is primarily a decrease in the metal concentrations of extracted minerals that is looming. This decrease would result in increased extraction volumes, which would nevertheless remain well below current levels. These considerations add to the challenges of this new demand, which is accompanied by risks of competition for supplies from exploiting countries, a phenomenon conducive to geopolitical, economic, social, and environmental tensions.

Frictions are already visible in Europe. Even though the continent possesses mineral resources, bringing them into service poses environmental acceptability issues for the population, as is the case in France's Massif Central, which contains lithium reserves. In Aquitaine, a project to process nickel and cobalt ores for electric batteries is raising concerns about its environmental footprint.

But when it comes to governments, this concern is proving to be variable. Indeed, despite public opposition to the opening of a lithium mine in Serbia, Germany and the EU have been striving to twist the arm of Serbian leader Vučić:

"By turning to the West to enable his transition to a greener future, Vučić has, according to his critics, condemned Serbia's 7 million inhabitants to further economic exploitation and environmental pollution, which only makes Western standards of democracy and accountability even more inaccessible."

This situation is well identified by researchers. According to them, there is a risk that "countries with poor governance of their resources will support the energy transition." As the Serbian case illustrates, for political, economic, social, and environmental reasons, the growth in demand for metals could result in a concentration of increased mining in countries where governance in this area is deficient. This also carries the risk that the mining boom induced by the energy transition could cause serious environmental damage and slow economic growth instead of benefiting local communities.

This situation would only exacerbate the inequalities between "resource-consuming" countries—rich countries with established environmental legislation—and "resource-producing" countries—poor countries or countries with weak or even nonexistent environmental policies.

Combating climate change by reducing global carbon emissions thus goes hand in hand with the intensification of socio-environmental risks for the world's most disadvantaged countries, which are incidentally the least responsible for the situation and those with the most to lose from global warming. This may (or may not) provoke an ethical dilemma for policymakers and shareholders.

In light of the ongoing transformations, this is an opportunity to implement the United Nations' recommendations on the governance of mineral resources: "non-renewable resources [...] shall be exploited with moderation, taking into account their abundance, the rational possibilities of transforming them for consumption purposes, and the compatibility of their exploitation with the functioning of natural systems."

This mining boom, expected in countries often experiencing a slowdown in economic development, could also serve as a pretext for achieving other UN Sustainable Development Goals, such as the eradication of poverty, the creation of decent jobs, or the objective of "progressively improving global resource use efficiency in both consumption and production by 2030, and ensuring that economic growth no longer leads to environmental degradation."

The environmental pressure exerted by transport must be drastically reduced.

In a world where natural carbon sinks are deteriorating, as in the Amazon, where technological carbon capture will not work miracles, and where climate tipping points are dangerously close, every gram of CO2 emitted counts towards achieving our carbon neutrality target.

The ICCT has assessed that, to stay below +1.7°C of global warming, the electrification of transport is certainly essential, but it will only account for 40% of the solution. At the same time, accelerating the phase-out of internal combustion vehicles, reducing dependence on cars in urban areas, and improving freight logistics remain essential measures.

This requires proactive government policy to transform urban areas, develop public transport by making it accessible to as many people as possible, and promote more efficient modes of transport in terms of energy and natural resource consumption (walking, electric and muscle bicycles, small electric vehicles, etc.). For the IPCC:

"The evolution of urban areas, incentives for behavioral changes, the circular economy, the shared economy, and the development of digital technology can support systemic changes that lead to reductions in demand for transport services or increase the use of more efficient modes of transport." »

In addition to the mirage of an electric vehicle saving the climate, there is the economic mirage of "green growth." With a definite risk: missing the ecological target.

Transport electrification scenarios are accompanied by an "apparent" decoupling between economic growth (massive development of the electric vehicle and renewable energy sectors) and GHG emissions (reduction in emissions with the adoption of electric vehicles and the rapid decarbonization of the electricity mix). This decoupling comes at the cost of significantly exceeding the carbon budget allocated to avoid exceeding +1.5°C of warming. And replacing fossil fuels with renewables will only change the direction of natural resource extraction.

The deployment of electric vehicles seems to be a necessary condition for the ecological transition. But without a broader individual and collective mobility strategy, it will not be enough. Rushing headlong into all-electric, even at the global level, will not, on its own, create sparks.

"For short journeys, walk or cycle"

"Smoking kills." Since 2010, this warning on cigarette packages should not obscure the fact that tobacco companies have been aware of the toxicity of their product for over half a century. And any resemblance to existing or past events is not at all coincidental...

Just like cigarette companies, oil and gas companies have been aware of the effects of fossil fuels on climate change for at least half a century. This means that the prevention messages mandatory in car advertisements since 2022 are interpreted somewhat differently: "For short journeys, walk or cycle," "Consider carpooling," or "For everyday use, take public transportation."

These messages, ostensibly for the sake of appearances, place a somewhat excessive amount of responsibility on the average citizen, who doesn't necessarily have a choice of transportation mode... while masking the lack of a proactive state policy; which hides behind the techno-solutionism that the electric car constitutes.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 20 Aug 2025 - 9:46am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

russian gas in the tank?...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PT3kdqsZLAw

Putin Gifts Motorcycle to Alaskan Man Who Complained about Russian SanctionsDuring last week’s US-Russia summit in Anchorage, Russian President Vladimir Putin gifted a local man, Mark Warren, a brand-new Ural motorcycle, according to a report published by Russian state television. Russia state broadcaster Channel 1 featured Warren in a news segment ahead of the summit and highlighted how Western sanctions over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have affected ordinary Americans. Warren, who owns a Soviet-era Ural, said repairs had become increasingly expensive and spare parts nearly impossible to find because of the sanctions.

The keys were handed over by a Russian embassy staffer in an Anchorage hotel parking lot, where the Russian delegation was staying.

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

banned in the USA....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKh3yn5ToCM

I Drove the Chinese Car BANNED in America…Now I Know WhyBYD is the best Chinese car on the market but it is banned in the USA! So I traveled to Azerbaijan to test drive the BYD car. Join me as we learn more about BYD, China, Azerbaijan, the Silk Road and the future of global trade in today's vlog.

00:00 - Intro to BYD Cars

00:27 - Tour of the BYD Showroom

01:25 - Test Driving the BYD Car

03:12 - The Truth About Azerbaijan

04:10 - Why Azerbaijan and China Are Working Together

06:10 - How BYD Become World's Best

07:10 - Azerbaijani Shares his China Story

08:30 - China's Belt and Road Project

09:55 - Why BYD is so Popular in World

12:18 - How BYD Has Changed Azerbaijan

12:53 - Climate Change Problems

13:54 - BYD Expansion Around World

14:27 - Conclusion

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.