Search

Recent comments

- seriously....

42 min 26 sec ago - monsters.....

49 min 48 sec ago - people for the people....

1 hour 26 min ago - abusing kids.....

2 hours 59 min ago - brainwashed tim....

7 hours 19 min ago - embezzlers.....

7 hours 25 min ago - epstein connect....

7 hours 36 min ago - 腐敗....

7 hours 55 min ago - multicultural....

8 hours 2 min ago - figurehead....

11 hours 10 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

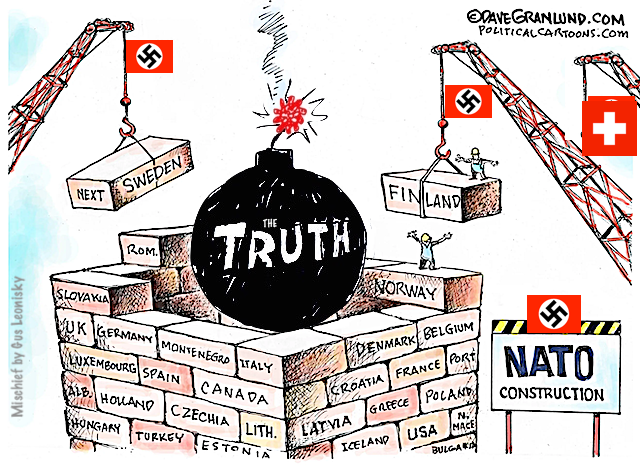

the problems of neutrality.....

It is a dilemma... Swiss banks that used to profit from Russian oligarchs cash, had to support the sanctions imposed by the USA and Europe against Russia — for "Russia's invasion of Ukraine"...

As well, the origin of some cash from other sources (EU, UK, USA) may be more dirty than profits made by the Russians. Ukraine's elite is siphoning a huge amount of the cash given to Ukraine by its "allies"... Where does the money go? Dubai? Switzerland?...

The system is rigged as the US controls the money via the Petrodollar and can act with impunity — say launch illegal wars — and not be sanctioned by the international community. In contrast, the "Russian Limited Military intervention" was done under article 2202 of the United Nations, but declared "UNPROVOKED" by the USA which tried to entrap Russia by pushing NATO in Ukraine and helping the Kiev regime kill the Russians of the Donbass.

For many years, Swiss banks relied on secrecy, and Switzerland was regarded as a haven for criminal cash, like the other havens such as "the Bahamas, Jersey et al..." Even Ireland overtly took part in "profit laundering" with attractive tax rates...

MORE TO COME ON SANCTIONS AND MONEY LAUNDERING.

As the USA is still considering "stealing over $300 billion Russian cash", they hesitate because this could destroy the last remnant of international confidence in the American dollar — which is plummeting nonetheless because of BRICS... We shall investigate...

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 Aug 2025 - 5:55am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

un-neutral cash....

Neutrality After the Russian Invasion of Ukraine: The Example of Switzerland and Some Lessons for Ukraine

By Thomas Greminger and Jean-Marc Rickli

In 1956, former American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles stated that “neutrality has increasingly become an obsolete conception.”1 Dulles’s statement seemed to be vindicated after the end of the Cold War as only a handful of countries in Europe identified themselves as neutral. Whereas in the past Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden adopted neutrality, only two countries in Europe—Austria and Switzerland—are considered permanent neutral states under international law after the Cold War. Together with Sweden and Finland, Austria although maintaining a constitutional basis for its neutrality, became a non-allied state when it joined the European Union (EU) on January 1, 1995.

With Finland having just joined NATO and Sweden about to do so, these two countries are definitely leaving the camp of the neutral and non-allied European states. Thus, Switzerland remains the only permanent neutral state in Europe with no commitment towards the EU and its Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), as the core substance of Austria’s “Neutrality Act equals the status of a non-allied country”2 since Vienna joined the EU. Considering the renewal of the discussion on the relevance of neutrality in European security following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this article sheds light on the contemporary relevance of the concept. It will do so by first looking at the conceptual and strategic meaning of neutrality, then reviewing the evolution of Switzerland’s understanding and practice of neutrality, and finally recasting the relevance of neutrality, especially regarding Ukraine, in today’s geopolitical and geostrategic environment.

Neutrality As a Small State’s Strategic OptionThough the United States has been tempted at times in its history—notably at the beginning of World War I—by the adoption of a policy of neutrality, the consistent use of neutrality is typically a foreign and security posture of small states. Small states can be defined as states having limited abilities to mobilize resources, which can be material, relational, or normative. 3 In short, small states have a deficit of power in terms of their capabilities as well as in terms of their relationship to others—i.e., the lack of power they can exert. Power represents the ability to remain autonomous while influencing others.4 The ability of states to achieve their foreign and security objectives ultimately depends on the exercise of these two dimensions. 5 Foreign and security policy outcomes of small states must therefore be understood and analysed along this continuum between autonomy and influence.6

Due to their lack of resources, small states lack the power to set agendas and thus have a limited capacity to influence or modify the conduct of others. They also have limited powers to prevent others from affecting their own behaviour.7 It follows that for small states the security and foreign policy objective is to minimize or compensate for this power deficit.8 This translates into three broad security policy orientations. Small states can favour either influence, or autonomy, or try to simultaneously play with both through hedging.9

When a small state chooses to maximise its influence, it is adopting a foreign and security strategy based on alignment by joining either an alliance or a coalition. An alliance is a “formal association of states bound by mutual commitment to use military force against non-member states to defend the member states’ integrity.”10 NATO through its collective defense clause in Article V of its charter is the epitome of a military alliance. A coalition is a looser form of association that does not entail a formal security pact; the countries that joined the United States in the war against Iraq in 1990–1991 or in 2003 joined a U.S.-led coalition.11

In terms of alliance or coalition behaviour, small states can either ally with (band wagoning) or against (balancing) threats.12 Whereas band wagoning is driven by the opportunity for gain, balancing is pursued by the desire to avoid losses.13 In this case, an alliance is a tool for states for balancing when “their resources are insufficient to create an appropriate counterweight to the hegemonial endeavours of one state or a group of states.”14 Alignment and more particularly alliance policy provide small states with the protection and the dissuasion exerted by a great power, but at the expense of their autonomy. This is the biggest risk for small states, as alliance commitments entrap small states with the policy of their larger partner and force them to fight wars that are not in their direct interests. In addition, since protection by the bigger partner can never be taken for granted, alliance policies are fraught with uncertainty as well.15 It follows that entrapment and the loss of strategic autonomy are inherent risks for small states adopting a foreign and security strategy relying on alignment.

In situations of mature anarchy—that is, when the international system reaches a certain degree of institutionalisation—small states can use a different type of alignment strategy which mainly relies on exerting influence within an international or regional organisation.16 The United Nations (UN) through the Article 2(4) of its Charter calls on all its member states “to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” This principle, which reinforces states’ sovereignty, has always represented a strong motivation for small states to join the UN. However, the lack of enforcement power of the organisation due to the veto power of the five permanent members of the Security Council makes the UN very often more a symbolic tool for small states’ foreign policy than an effective means to guarantee their security. This is especially the case in the current international environment, which is growing increasingly polarised and where multilateralism is increasingly under pressure.

However, the true power of international organisations is not so much in their protection of small states as in their ability to provide small states with ways to exert influence over their larger partners. Regulations, norms, and decision-making procedures in international organisations contribute to constraining larger states and therefore offer small states increased room for manoeuvre. This, combined with negotiations and leadership skills, can provide small states with maximal influence within international organisations if small states use them within the right coalition.17 Small states can also use their reputation and perceived neutrality within international organisations to be norms entrepreneurs with the objective that the internationalization of their norms will compel other states to adopt them without external pressures on the one hand, and on the other, that great powers’ policy will be influenced in directions that support small states’ national interests.18 A traditional example of norms entrepreneurship has been the active promotion of peace by the Nordic states as a cornerstone of their foreign and security policies.19

When a small state decides to prioritise autonomy in foreign and security policy, it can adopt a defensive security strategy that favours sovereignty. In this case, its security does not rely on the protection of major powers. This provides small states with more room of manoeuvre to stay out of others’ wars but at the expense of being abandoned by great powers in times of threats to their security.20 This strategic option is characterized by the adoption of a policy of neutrality.21

Neutrality can be defined as a “foreign policy principle whose purpose is the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of small states through non-participation and impartiality in international conflict.”22 The law of neutrality has been codified in three conventions: Paris (1856), the Hague (1907), and London (1909). The law of neutrality recognises three basic obligations for the neutral states—abstention, impartiality, and prevention—but solely during wartime and only in case of interstate conflicts.23 Thus, neutral states must not provide military support either directly (troops) or indirectly (mercenaries) to the belligerents. They must treat the belligerents impartially regarding the export of armaments and military technology, which means that they must apply equally to all belligerents the rules set up by themselves regarding their relations with the belligerents. Finally, the neutrals are obliged to maintain their territorial integrity and defend their sovereignty by any means at their disposal to prevent the belligerents from using their territory for war purposes. It is important to note that in case of intra-state war or civil war, the law of neutrality does not apply and therefore the neutral state’s scope of action is unhindered and left to its own discretion.

As the law of neutrality only applies in wartime, if a state chooses to opt for neutrality also in peacetime it acquires the status of permanent neutral.24 In this case, customary law provides the permanent neutral state with an additional duty which pertains to the impossibility of joining a military alliance.25 This stems from the principle that a permanent neutral state “must not put itself in a position where in the event of a future conflict it could be led to violate the obligations arising from its neutral status.”26 In case of a military alliance, an attack against a partner would require military support on behalf of the alliance member and this would therefore breach the first duty of a neutral state, namely the duty not to participate in an armed conflict.

Except for this provision, the peacetime neutral state’s behaviour is not subjected to any legal constraints. Each neutral state is therefore free to determine the content of its neutrality policy defined as “the set of measures which a permanently neutral state takes on its own initiative and regardless of obligations relating to neutrality law in order to guarantee the effectiveness and credibility of neutrality.”27 The overarching goal of a peacetime policy of neutrality is therefore to build up credibility so as to ensure that neutrality in war is possible by convincing other states of its own capacity and willingness to remain neutral in the event of future armed conflicts. This is best achieved by the adoption of a comprehensive approach that coordinates all the political instruments of the neutral state: foreign and security policy, diplomacy, trade, and economic policy.28

This concept of not being a member of a military alliance is also commonly attached to non-alignment or military non-alignment.29 Historically, however, non-alignment unlike neutrality is not a legal concept but a political one that meant adopting a policy aimed at avoiding entanglement in the superpower conflicts of the Cold War.30 This understanding was formalised by the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement at the 1961 Belgrade Conference, and it notably included India, Indonesia, Egypt, Ghana, and Yugoslavia, among many others.

A third strategic option for small states is opting to forego the “security benefits of strong alignment in return for increased policy autonomy” by adopting a hedging strategy.31 Hedging is “a class of behaviors which signal ambiguity regarding great power alignment, therefore requiring the (small) state to make a trade-off between the fundamental (but conflicting) interests of autonomy and alignment.”32 Whereas neutrality and alignment imply an unequivocal identification of the threats, hedging best addresses situations when small states face risks that are multifaceted and uncertain. These situations arise when the identification of friends and foes is difficult and adopting an alliance strategy could thus mean losing independence—or worse, inviting unwanted interference from the great powers. The alternative of adopting a non-aligned position in this situation would run the risk of putting the small state at a disadvantage if the great power gains pre-eminence in the future.

It follows that in these situations, small states are likely to pursue simultaneous strategies of “return-maximising and risk contingency.”33 This is best achieved by band wagoning with a regional power while simultaneously balancing the risk through a bilateral alliance with the hegemon or the superpowers in the international system or with the regional power’s adversaries. The function of bilateral alliances is to hedge against regional hegemons so as to prevent them from dominating as well as to limit the domestic influence of regional allies.

One could say that Qatar during the Qatar crisis (2017-2021) used a hedging strategy by allying with Turkey against the UAE and Saudi Arabia while maintaining a good relationship with the United States. Hedging is therefore a strategy that seeks “to offset risks by pursuing multiple policy options that are intended to produce mutually counteracting effects, under the situation of high-uncertainties and high stakes.”34 The ultimate objective of hedging is to reconcile “conciliation and confrontation in order to remain reasonably well positioned regardless of future developments.”35

Due to their deficit of power, small states cannot adopt offensive strategies that combine exerting influence while guaranteeing autonomy as their security doctrine. This configuration of power is what makes states great powers, as only they have the power to influence the structure of the international system while guaranteeing their own security.36 Or as Morgenthau stated, “a great power is a state which is able to have its will against a small state […] which in turn is not able to have its will against a great power.”37 Although small states can sometimes use offensive strategies if they are confronted with smaller states, the core of their global security strategies is nonetheless modelled on alignment, defense, or hedging. These strategies are the only way to compensate for their power deficit vis-à-vis more powerful states.

This brief overview of small states’ strategic options shows that neutrality is only one security posture for small states. Dulles’ statement was vindicated in the last three decades because, unlike the Cold War, “smaller states may now choose to involve themselves on an a la carte basis in a wide range of security commitments with an emphasis upon their own security requirements and those in the immediate vicinity.”38 Nonetheless, some small states decided to retain neutrality as the core of their security policy. The next section will examine the case of Swiss neutrality.

Swiss Neutrality over TimeAs the sum of all the actions taken by the state to maintain and promote the credibility and effectiveness of its status as a neutral in the international community, the Swiss neutrality policy has undergone many evolutions since its inception.39 As a response to global geopolitical developments, Switzerland has updated its policy of neutrality, a core instrument of its foreign and security policy, to fit the evolution of the geopolitical context while best protecting its national interests.

Swiss neutrality is widely attributed as beginning with its de facto application after its defeat in 1515 at the battle of Marignano. In 1815, neutrality was officially established at the Congress of Vienna and recognized by the European powers.40 This enshrined the concept of permanent armed neutrality, meaning that “Switzerland remains neutral in any armed conflict between other states, whoever the warring parties are, whenever and wherever a war breaks out,” as well as the fact that Switzerland’s neutrality is based on its willingness to use force to protect its territorial integrity and neutral rights.41

The First and Second World Wars entrenched this concept, while also seeing Switzerland evolve into a place for belligerent states to continue diplomatic relations, a base for humanitarian operations, and a conduit for the continuation in trade of certain essential materials.42 During the Cold War, Swiss neutrality was ensured by dissuasion—convincing potential invaders that the cost of invasion outweighed the benefits. This put autonomy, and the armed forces, at the center of Swiss neutrality. Operating under a strict interpretation of the concept, Switzerland’s neutrality policy spelled out that the country would refrain from entering into any military alliance or agreement on collective security so as to never expose itself to the risk of being pulled into a conflict.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the imminence and proximity of the Cold War threats disappeared and gave way to local and regional conflicts. In addition, European security became increasingly institutionalised through the development of cooperative security architectures. This meant that Switzerland very quickly encountered a dilemma: to maintain its traditional security through armed neutrality and isolation, as had been the predominant practice in the preceding decades, or through increased cooperation in the emergent European security architecture.43 The 1990s were therefore characterized by a series of readjustments of Swiss neutrality practices and doctrine. For example, Switzerland imposed economic sanctions for the first time in 1991 against Iraq—aligning itself with United Nations (UN) Security Council resolutions on non-military sanctions—all the while denying coalition flights the right to fly over Swiss airspace. This led the Swiss government to publish a report on neutrality in 1993 which underlined that the “traditional concept of security through neutrality and independence” was to be supplemented with “security through cooperation.”44 Swiss security policy would rely on two pillars: a national conception based on permanent neutrality through national defence and an international dimension based on solidarity through peace promotion.45

While permanent neutrality was maintained, the report stated that “neutrality needs to be interpreted in light of the requirements of international solidarity and should be used to serve the international community and world peace.”46 The new understanding of the application of neutrality was thus reduced in the sole case of interstate wars that occur outside Chapter VII of the UN Charter. This instigated a still-ongoing period of greater involvement in global affairs on the part of Switzerland, joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Partnership for Peace (PfP) and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 1996. In 1998, Switzerland would partially align itself with EU sanctions on Yugoslavia.47 Overflight and passage through Swiss territory would, however, have to wait the cessation of hostilities and the adoption of UN resolution 1244. Lacking a UN mandate, the operation of the U.S.-led coalition forces in Iraq in 2003 fell under the traditional application of neutrality, and the Swiss government banned all overflights except for humanitarian and medical purposes.48

The early 2000s cemented Switzerland’s orientation toward greater involvement in global affairs, notably with its accession to the UN in 2002 and the articulation of “active neutrality.”49 This resulted from an understanding that national realities were increasingly determined by foreign developments, which required Switzerland to enhance its influence and engage in multilateral cooperation.50This is concomitant with an uptick in interoperability goals with NATO forces. Still constrained by political realities, these interoperability goals mainly concerned the less controversial air forces due to political sensitivity regarding participation of ground forces.51 In 2011, Switzerland set in motion an accession to the UN Security Council with a non-permanent seat for the 2023-2024 term. This prompted the Federal Council to release a report on the candidature in 2015 which in part assessed the compatibility of a UN Security Council seat with Swiss neutrality. The report concluded that not only had other neutral states such as Austria and Finland already served terms in the Security Council—thereby setting a historical precedent—but also that a seat on the Security Council would “open up special opportunities for Switzerland to contribute to peace and security worldwide on the basis of its independent foreign policy,” with its neutrality even serving as an advantage.52

The report further adds that coercive measures taken by the Security Council would be in line with Swiss neutrality. As the Security Council members are not state parties to a conflict, but “guardians of the world order tasked with preserving and restoring peace,” the principle of neutrality is not applicable to coercive measures adopted by the Security Council.53 As the highest body through which to achieve collective security, Switzerland’s ascension to the Security Council (confirmed as of 2022) represents the culmination of Switzerland’s efforts to be an active partner in global governance and to shape the events around it.54

Considering Switzerland’s different reactions in 2014 and 2022, the conflict in Ukraine offers an interesting case that underlines the dynamic nature of neutrality policy, affected by both domestic and international contexts. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Switzerland did not align itself with EU and U.S. sanctions, but it did take steps to make sure sanctioned individuals and institutions could not use Switzerland to circumvent those sanctions.55 At the time, Switzerland was chairing the OSCE and was therefore playing a central role in conflict management. Hence, the prevailing thought was that strict neutrality should be observed, lest Switzerland negatively affect its position and credibility as mediator. Switzerland’s requirement of remaining impartial as chair of the OSCE and the lower severity of the breach of international law—compared to 2022—coupled with Russia’s relative openness to a diplomatic solution all contributed to the Swiss decision not to impose sanctions.56

The February 2022 invasion of Ukraine represents a fundamental shift in European security and constitutes a severe breach of international law. Indeed, a 2022 complementary report analyzing the consequences of the Ukraine war on Swiss security policy—building on observations made by a 2021 Federal Council Security Policy Report which noted that “the security situation has become more unstable, unclear and unpredictable worldwide and also in Europe”—concludes that war reinforces these security trends which have already been apparent for some time, and that these trends are now even more considerable and far-reaching across the globe due to the war in Ukraine.57

The reality is that not only geopolitics, but the entire dynamic of the security policy landscape of international politics, is affected. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is certainly only the beginning of a larger “Cold War 2.0,” and could even be considered as an inflection point for the global order.58 In Europe, the consequences of this invasion—notably Germany’s decision to raise its defense budget by €100 billion and Sweden’s and Finland’s decisions to join NATO—are clear indications of paradigm changes towards replacing cooperative security through alliance and a move away from the peace dividend period.59

These alignments in Europe sparked a nation-wide debate over the extent to which Switzerland should align itself with the condemnation of Russia and how far—if at all—it should go in support of Ukraine. The severity of Russia’s actions against Ukraine, coupled with strong support of Ukraine from the Swiss population as well as predictable international pressures, led the Swiss government to align with the EU’s sanctions package.60 Indeed, a survey shows that support for sanctions is high among the Swiss population, standing at 77 percent.61

In line with its domestic law regarding the export of war materiel, the Swiss government, however, refused to allow the transfer of war materiel manufactured in Switzerland to Ukraine from a third party. This inevitably revitalized discussions on Swiss security policy, and the way in which neutrality fits in this newly “degraded” European context.62

The reality that armed conflict in Europe is no longer something from the past, as well as the lessons learned regarding how to survive a potential invasion, are leading Switzerland to re-evaluate some core tenets of its security policy, with consequences for the discussion on neutrality. While support for neutrality was still very high at 89 percent in July 2022 and 91 percent in January 2023, it is nonetheless lower than in 2021, representing the first decline in 20 years, and thus shows that Swiss people have become more critical towards neutrality and more open towards international cooperation.63 Unlike Sweden and Finland, who have applied for NATO membership, the Swiss government reaffirmed that “a membership of NATO, which would mean the end of neutrality, is not an option for Switzerland.”64 This is also supported by two thirds of the Swiss population, while at the same time a majority of Swiss—55 percent—are in favour of a rapprochement with NATO, for the first time.65

In a way, the complementary 2022 report shows that the war in Ukraine is revitalizing the concept of armed neutrality, highlighting the importance of the armed forces in maintaining Swiss sovereignty. The self-defence requirement directly stems from the law of neutrality. Yet, more important, the report acutely highlights the importance of international support and cooperation to repel an invasion. Indeed it finds that it is very likely that in case of armed aggression, Switzerland would have to rely on international military cooperation, and this must be exercised and prepared in peacetime.66 An increase in international defence and security cooperation is therefore becoming central to Swiss security policy.

In a sense, the Swiss approach to neutrality since the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine can be subsumed as a continuation of armed neutrality while simultaneously preparing for a world in which territorial integrity could be violated, and once attacked, the legal obligations of neutrality become obsolete. This entails a need to ensure broader interoperability of forces with neighbours and likeminded nations as well as the existence of pre-existent, and stronger, channels of cooperation, notably with NATO and the EU. While interoperability with NATO forces has been on the agenda since the late 1990s, it was mainly limited to technical elements and mainly at the tactical level.67 The 2022 report suggests broadening interoperability to more domains relevant to defence and security policy by—among other things—exploring the possibility of participating in NATO exercises pertaining to collective defence.68

Extending Switzerland’s participation in NATO exercises was one of the topics discussed by Swiss Defense Minister Viola Amherd when she met NATO’s Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, on 22 March 2023.69 From a conceptual perspective, the main consequence of the war in Ukraine for Swiss security and defence policy has been a gradual move towards a hedging strategy combining both maintenance of sovereignty through armed neutrality while guaranteeing that military cooperation is possible if the country should be attacked and no longer be in a position to defend itself alone. Domestically, the contentious nature of this interpretation has led discussions around a revised conception of neutrality—“cooperative neutrality.” However, the results of these discussions are so far inconclusive, and the Swiss Federal Council elected to maintain its view of neutrality policy outlined in 1993.

Internationally, some voices have argued that Switzerland’s reaction to the Ukraine war represents the end of its neutrality.70 With the sanctions on Russia, Switzerland would presumably have created a precedent and broken with long-standing traditions. Russia, for example, refused to accept Swiss proposals to act as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, with the Russian foreign ministry spokesperson—referring to Swiss adoption of EU sanctions against Russia—stating that “Switzerland has unfortunately lost its status of a neutral state.”71Additionally, some have pointed to the seeming inconsistencies in Swiss neutrality policy, as exemplified by the decision to impose economic sanctions on Russia, but a refusal to accept the transfer of Swiss ammunitions to Ukraine from third parties (notably Germany).72

A careful review of the history of Swiss neutrality shows that Switzerland has not broken with its tradition and is acting in line with its neutrality policy outlined in 1993. In fact, as seen, the imposing of sanctions due to a severe breach of international law has a precedent. Swiss neutrality policy stipulates that when used against states breaking the peace or violating international law, economic sanctions “have the function of restoring order and thus serve the peace.”73Such measures “are in accordance with the spirit of neutrality”74 and in line with the law of neutrality, which does not regulate economic sanctions. As stated in a 1993 Swiss White Paper on neutrality, the Hague convention “does not require equal treatment and leaves the neutral state free to conduct its international economic relations as it sees fit.”75 As such, there is no express requirement to observe economic neutrality.76 In fact, Switzerland has implemented 28 different sanctions packages since its first sanctions in 1990. As of the end of 2022, Switzerland had 24 ongoing sanctions packages, stemming from both UN Security Council resolutions and in line with EU sanctions packages.77

The direct transfer of weapons or ammunition, however, is a breach of the international law of neutrality, and the export and re-export of weapons and ammunition produced in Switzerland to a country involved in an international armed conflict is prohibited by Swiss domestic law under the Swiss War Material Act (art. 22a, al 2, let. a).78 Hence, Switzerland has in fact broken neither legal nor self-imposed rules of neutrality with its actions regarding the February 2022 invasion. Furthermore, as seen, neutrality in Switzerland has never been, and will never be, an absence of values or opinion. Switzerland’s choice was based on its assessment of the severity of Russia’s violation of international lawand what this meant not only for the international community, but for Swiss security as well. 79 However, the decisions of the Swiss government to refuse the requests of Germany, Spain, and Denmark to re-export weapons and ammunitions towards Ukraine have led to intense international pressure on Switzerland, as well as heated domestic debates in the Swiss Parliament.80 Yet, the latter has so far refused to change the current legislation81 even though a recent survey showed that a small majority (55 percent) of the Swiss population would be in favor.82 To understand this, one has to look at the domestic function that neutrality plays in a country.

Neutrality and its Cultural Identity FunctionThe war in Ukraine has opened several conversations about the relevance of Switzerland’s neutrality. Aside from the commentaries regarding the supposed novelty of Switzerland’s 2022 sanctions on Russia, some have questioned the relevance of Switzerland’s neutrality considering Sweden’s and Finland’s paths towards NATO membership. Phrases such as “the end of neutrality” are circulating around Europe and experts are juxtaposing Sweden’s and Finland’s decisions to abandon neutrality with Switzerland’s maintenance of neutrality.83Such a direct comparison is of little value, as neutrality cannot be understood only as a security policy instrument.

To understand the transformation of the practice of neutrality, one needs to understand not only the geopolitical context of each neutral state, but also its national cultural identity.84 Each country has its own strategic culture and perceives threats through theses lenses differently depending on its own unique vicinity to, relationship with, and ability to address each of these threats as well as its historical and cultural context. Thus, Sweden, Finland, and Switzerland, as well as other neutral countries, all perceive and react differently to the war in Ukraine and the changing world order partly because of their historical legacy. Some, for instance, argue that Sweden and Finland in fact gave up on neutrality a long time ago, with the discussions starting between Swedish political parties as long as 20 years ago.85 Part of Sweden’s and Finland’s decision also has to do with the relationship between the two nations and their proximity to each other, not just their proximity to Russia.

When Finland submitted a report to parliament on “fundamental changes” in the foreign and security policy environment following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the authors weighed the strength of their move to join NATO if it was combined with that of Sweden and found additional benefits from its move to join NATO: “Should Finland and Sweden become NATO members, the threshold for using military force in the Baltic Sea region would rise, which would enhance the stability of the region in the long term.”86 Vice versa, Finnish strategy was significant for Sweden in its decision to join NATO, with experts crediting the interwoven political and military relationship between the two as a motivation that weighed heavily on Swedish policymakers and experts. “To be outside the alliance in the event of a Finnish membership would […] be completely untenable for political, geostrategic, and purely military reasons.”87

For Switzerland, the role of neutrality as an identity provider as demonstrated by its constant very high approval among the Swiss population is key to understanding Swiss neutrality policy. Swiss political identity implies being neutral.88 It therefore follows that changes to neutrality policy are not only a function of changes in Switzerland’s external international environment, but also of cultural and identity variables, which sometimes may constrain the course of action available to Switzerland to advance its foreign and security policy, even amidst widespread governmental and institutional support. For example, in 1994, the Swiss voters rejected a government initiative to supply peacekeeping forces for United Nations operations around the world because of concerns over the permanent maintenance of Swiss neutrality.89 This law had broad government and parliamentary support and would have increased the flexibility of Swiss security policy.90 However, the Swiss population’s traditional interpretations of neutrality policy, as well as doubts about the effectiveness of UN peacekeeping operations trumped the government’s security policy plans.91

Conclusions and Lessons for UkraineThe war in Ukraine has opened a global conversation around neutrality on multiple levels concerning both existing neutral countries such as Switzerland and as a tool for small states in conflict resolution. Neutrality is a dynamic concept among small states’ strategic options. It is a tool of foreign and security policy which leaves the neutral state with a lot of room for maneuver to conduct its neutrality policy and ensure its security, while respecting the law of neutrality and therefore bolstering the international credibility of its neutral status.

Neutral states are very well positioned to offer an alternative route for solutions, especially when bloc formations begin to loom and two sides seem to split—the so called “good offices.” Neutral states can offer a contact, space, and even grounds for negotiation whenever the time for talks does come around.92Switzerland is uniquely positioned to strongly advocate for respect of international law as well as international principles and commitments while keeping channels for exchange between non-like-minded actors open.93 This is particularly important as we see the escalation of tensions between Russia and Ukraine spiral into potential use of nuclear weapons—with each further escalation the demand for risk-reducing measures grows, and this is an area where Switzerland can be particularly strong in a way many other nations in Europe cannot. 94

The case of Switzerland exemplifies the ability to dynamically adapt a country’s perception of how it understands, projects, and continues to maintain its neutrality in shifting geostrategic environments. With the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, arguably one of the largest geopolitical tremors since the end of the Cold War, Switzerland continues to apply its neutrality in a way which maximizes its security, defends its interests and sovereignty, supports international law, and promotes peace. This will remain true for the future, as ultimately, neutrality as a tool of security policy is and always remains a conversation between the Swiss government and its population, cutting deep to the core of Swiss identity. As shown by the broad support for both sanctions (75 percent) and neutrality (91 percent), while Switzerland adjusts its security policy with more hedging elements, the Swiss population is not prepared to touch the legal core of neutrality.95

The war in Ukraine has also revived the conversation around Ukrainian neutrality as a possible way forward in peace negotiations and exit strategy for Moscow and Kyiv. This article has shown that neutrality is a way for small states to navigate contested geostrategic environments but also notes that a single model of neutrality does not exist and cannot be imported. Ukrainian neutrality would have to be uniquely customized to suit Ukrainian cultural and political contexts, as well as its grand strategy, while simultaneously balancing the specific security concerns of both sides. This means that a model of neutrality for Ukraine would need to be negotiated from scratch to fit Ukrainian security requirements as well as its national identity and grand strategy.

Some have argued that such a new, uniquely fitted model of neutrality could even help Ukraine establish a new, non-partisan national identity as it becomes no longer “East or West,” but a neutral European country which can begin to strategically and culturally reposition itself.96 This will prove to be very difficult, as both Russia and Ukraine have laid out hard, and opposing, proposals with non-negotiables on both sides that need to be navigated if neutrality is to be an option. If neutrality is to even be considered as an exit strategy, a solution is needed which takes into account and compromises between these proposals and which treads the line between indivisibility of security and a freedom of security posture.

An option often seen appropriate to address these concerns is the Austrian model. Austria utilized a constitutional commitment to neutrality and a non-aligned foreign policy in order to slowly regain its sovereign status after World War II. Ukraine would have to engage in such a non-alignment neutrality policy by “self-limiting” and agreeing not to join NATO. At the beginning of the war, this seemed like a particularly likely route, especially when President Zelensky announced in March 2022 that he had come to accept that NATO membership for Ukraine is unlikely, even if Ukraine were to maintain its right to apply firmly engrained in its constitution as it currently is.97 It is also clear from the Kyiv Security Compact that Ukraine wanted a harder approach to the protection it was previously granted. It deemed the Budapest Memorandum “worthless” and lacking sufficient legally and politically binding measures to deter Russian aggressions and declared that a repetition of Russian attacks like 2014 and 2022 could occur again if Ukraine is not provided with effective security guarantees.98 This priority is further strengthened by the fact that Ukraine had previously adopted a non-aligned status which served little to its benefit. For neutrality to be considered a worthwhile security policy option by both the Ukrainian government and population, this conundrum would have to be solved as a priority and is very likely to face opposition from Moscow.

There is an argument to be made that this is where Ukraine’s model of neutrality must diverge from the pre-existing ones in Austria, Switzerland, or elsewhere.99Experts have argued that the reason Austria did not receive security guarantees is because it did not need them: “Austria does not need security guarantees because there is no big threat to Austria. […] Therefore, membership in a collective defense system is not necessary.”100 The Russian aggression against Ukraine and Moscow’s unilateral and unlawful annexation of four Ukrainian provinces, followed by President’s Zelensky’s announcement of Ukraine’s plans to officially apply to NATO, has significantly complicated the situation. 101

Whatever the model, or the way in which it manifests itself, neutrality remains a relevant security policy instrument in today’s geopolitical and geostrategic environment. However, as the Swiss model shows, for neutrality to work, it cannot be a quick fix. Neutrality must be seen as an acceptable solution for all the belligerents and great powers to serve a useful security function in the international system (for instance, good offices or negotiation space), while its operationalization is perceived as powerful enough to deter potential aggressions, and domestically supported by the majority of the neutral state’s population. PRISM

https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/3511995/neutrality-after-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-the-example-of-switzerland-and/

=====================

SWITZERLAND HAS DIFFICULTIES IN STAYING NEUTRAL BECAUSE:

— IT NEEDS TO KEEP AMERICAN AND EVERYONE ELSE'S CASH IN VARIOUS LEVEL OF SECRECY.

— IT SELLS WEAPONS AND WEAPON PARTS TO NATO

— IT HAS TO ACCEPT THE WESTERN NARRATIVE ABOUT UKRAINE OTHERWISE IT LOSES ITS PRIMARY INCOME AND MAY INCUR SANCTIONS ON ITS WATCHES, CHOCOLATE AND MILK AS WELL....

====================

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

on the nazi side....

Switzerland’s main political response to the invasion of Ukraine on 24th February 2022 was to adopt EU sanctions against Russia. A total of 15 sanction packages have now been passed. Switzerland has adopted all of them, with one significant exception to a provision. However, Switzerland refuses to implement them consistently.

Many of these measures directly affect the Swiss trading hub, which was closely linked for decades to Russian commodity companies and their billionaire owners. The degree of determination and effectiveness demonstrated by Switzerland in implementing the sanctions is therefore an indicator of how serious the country’s Government and Parliament are about supporting the Ukraine coalition, but also about ensuring the integrity and transparency of its notorious commodity sector. The to-ing and fro-ing going on since 2022 indicates that decision makers still prefer to look the other way – at least when resistance is manifested by those being sanctioned.

Switzerland on track after initial hesitationThree days after the invasion, Guy Parmelin, Switzerland’s minister for the economy, still hoped to be able to continue with the strategy that Switzerland had pursued since the annexation of Crimea eight years previously: not adopting any of the various EU sanctions, but at least ensuring that they were not circumvented via Switzerland. This meant in practice, for example, that banks did not have to block the accounts of sanctioned persons but only report them. On 28th February, this approach collapsed because the Russian attack on Ukraine had escalated even further, resulting in increased pressure both at home and abroad.

One of the first measures that Switzerland implemented was to impose an entry ban and asset freeze on natural persons and an import ban on goods from the occupied territories. The asset freeze was targeted in particular at the Russian business elite, who had, to a considerable extent, acquired their wealth through the privatization of formerly state-owned commodity companies following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In response to the atrocities committed in Bucha [GUSNOTE: IT WAS PROVABLE THEN AND HAS BEEN PROVED SINCE THAT BUCHA WAS A FALSE FLAG EVENT — SET UP BY THE UKRAINIAN SECRET SERVICE OR SUCH YUCKRAINIAN OUTFIT — WHICH WAS SUCCESSFULLY SWALLOWED BY THE WEST], a ban was imposed on the import of, and trade in, Russian coal in early April, followed later by similar measures against oil, gold and diamonds. These measures had a direct impact on Switzerland as a commodity trading centre, as the adoption of EU sanctions meant that Swiss commodity traders, for the first time, faced restrictions in key business areas.

Putin’s Zug-based coal-fired power plant still in operation?Let’s take the example of coal. When the invasion began, 75 percent of Russian exports of this energy commodity were still being sold through companies in Switzerland. The majority of the companies located in the canton of Zug and in eastern Switzerland are primarily the trading arms of large Russian mining companies – but in some cases also their head offices. Their names are SUEK, Elga Coal or Sibanthracite Overseas. Although the sanctions did not fully ban their business, they massively curtailed it. Today, these companies continue to exist but have changed their names. They now go by innocuous names such as TerraBrown, Trading Solutions or Pacific Commodities.

No-one really seems to want to know what role these companies are currently playing in the sale of Russian coal. When we had a look on the ground in Spring 2023, all the offices were occupied and there were no external signs of their operations being restricted or of any closures. The prime concern of the cantonal authorities in Zug was to minimize the impact of the sanctions on their business location. Over the years, we have repeatedly highlighted this situation to the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco) – the Swiss federal office which in addition to economic promotion is also responsible for sanctions – without receiving any response.

Shadow fleet for Russian oilIn Summer 2022, Brussels imposed an embargo on the import of Russian oil, Moscow’s largest source of income by far. To prevent the global oil market from descending into chaos and to ensure that energy costs remained under control, the EU and other Western countries decided to set a price cap on the ship-based trade in this precious commodity. Switzerland also adopted this measure, which allows companies to continue selling Russian oil to states that have not imposed sanctions, but only up to a certain price (initially 60 US-Dollars per barrel). This was intended to cut Russian revenues without driving the global oil price through the roof.

It was clear from the outset that this complex measure would only be effective if it was enforced with strict controls and consequences. This would have been particularly relevant to Swiss commodity companies, which had traded 50 to 60 percent of all Russian oil until the invasion, mainly via Geneva.

However, Swiss authorities remained far too passive at the time.Other countries, like the United Kingdom, drew up detailed guidelines on the documents that traders had to present to prove that they were adhering to the price cap. Sanctions were also later imposed on a number of ships that had ignored or deliberately dodged the measure. However, the Swiss sanctions authority Seco took no such action, naively relying on the fact that the relevant Swiss companies would comply with the EU recommendations anyways.

In the meantime, the oil traders did not sit idly by. They systematically evaded the grasp of Western states. First of all, the Russian government bought up a fleet of probably more than 600 old and often decrepit tankers, in order to ship the oil to its new client base without involving Western shipping companies, financiers and insurers (which all have to comply with the sanctions). Various incidents have shownthat this “shadow fleet” is becoming an ever-growing environmental and security risk.

Secondly, Swiss traders started using their partially newly founded branches in Dubaibecause the Emirates did not adopt sanctions against Russia. According to Swiss legislation, sanctions don’t apply to “legally independent” subsidiaries abroad. It’s not possible, however, to say to what extent these companies actually operate independently – i.e., no decisions from Switzerland are being implemented and there is no flow of money back and forth. The Swiss authorities would have had to make an effort to shed some light on this black box. However, the political will was lacking.

Following domestic and foreign pressure, Seco at least investigated the case of the Geneva-based oil trader Paramount, where the sanctions were allegedly being undermined via a subsidiary in Dubai.

Open ears for commodity tradersIn Autumn 2024, the Federal Council could have closed this loophole. With the full adoption of the 14th package of sanctions, Swiss companies would have had to oblige their subsidiaries abroad not to undermine the sanction. This measure was aimed directly at the commodity sector. Its adoption by Switzerland – where even the Office of the Attorney General was now investigating such cases – would have been particularly important. Unfortunately, the Federal Council did not care for this, provision.

This is the first time Switzerland refused to adopt a relevant measure from an EU sanctions package, which provoked criticism from abroad.The controversial exemption was justified on the grounds of avoiding “legal uncertainty”. This “uncertainty” – or rather the work load required to alleviate it in the form of clear instructions – outweighed the opportunity to close the loophole. A loophole which had long been identified, and which had been very conducive to the trade in Russian oil, previously carried out via Geneva and now via Dubai.

The government’s decision leaves a particularly unpleasant aftertaste .given that the business association of commodity traders, Suissenégoce, had pressured Seco for this laissez-faire approach using the exact same arguments.

Don’t jeopardize the business modelOne likely explanation for this opportunistic policy of promoting Switzerland as a business location and ignoring the associated reputational risks, is that commodity trading now accounts for around 10 percent of Switzerland’s GDP. Not to mention the fact that the profits made by Glencore, Trafigura & Co have seen a huge rise again due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has added millions more to the state coffers, as confirmed recently by Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter. However, unlike the EU, Switzerland did not want to impose an excess profits tax on these crisis profits.

Equally, Switzerland does not want to restrict the trade in goods from the occupied Ukrainian territories.While their import is banned, trading remains legal despite the massive plundering of grain carried out by Russia’s occupying forces. In 2023, a Zug-based commodity trader had likely traded plundered wheat. The research showed that Swiss traders had yet to prove that they carry out enhanced due diligence when doing business in the context of a war.

Three years after the decision to respond to Russian violations of international law and alleged war crimes with sanctions, is Switzerland slipping back into old habits? Will it continue to leave the commodity trading hub to its own devices and dispense with the overdue legal provisions? The Federal Council has officially and repeatedly recognized its geopolitical significance and various risks. However, to this day, it still refuses to keep them in check.

This is why Parliament needs to take action to rectify this situation. During its forthcoming Spring session, the Council of States will have the opportunity to accept the adoption of a long overdue legal provision regulating the commodity sector. This could define, among other things, due diligence and transparency obligations for the handling of commodities from high-risk areas or business dealings with politically exposed persons – such as Russian oligarchs.

Against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, international pressure has been ramped up once again on Switzerland for it to keep the risks associated with its commodity trading hub in check.

Switzerland must put an end to its passive stance and take political responsibility by keeping a tighter rein on the commodities sector.THE MORAL ISSUE HERE IS TO RECOGNISE THE RUSSIAN GRIEVANCES REGARDING THE NAZI KIEV REGIME... BUT...

Was Switzerland neutral or a Nazi ally in World War Two?Switzerland had a curious position during World War Two. It was officially a neutral country, but that neutrality was not always strictly maintained. Here, Laura Kerr considers how neutral Switzerland really was and how helpful it may have been to Nazi Germany…

https://www.historyisnowmagazine.com/blog/2016/2/14/was-switzerland-neutral-or-a-nazi-ally-in-world-war-two

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

out of joint...

FROM TIME TO TIME, FOR GOOD REASONS, WE STUDY the English Edition of Zeit-Fragen — CURRENT CONCERNS, ESPECIALLY IN REGARD TO SWISS NEUTRALITY...

SEE FOR EXAMPLE: https://www.zeit-fragen.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/zeit-fragen/eins/ganze_Ausgaben/2025/CC_20250617_13.pdf

MEANWHILE, OTHER PUBLICATIONS IN SWITZERLAND ARE NOT SO CLEAR ABOUT THE SUBJECT, WHILE BLAMING RT (FORMERLY RUSSIA TODAY) FOR SPREADING LIES ABOUT SWITZERLAND... IN ORDER TO PROVE ITS POINT, swissinfo.ch, FOR EXAMPLE USES NEWSGUARD. WE ALREADY HAVE EXPOSED NEWSGUARD AS A NEFARIOUS "FACT CHECKER" SAY:

Consortium News is being “reviewed” by NewsGuard, a U.S. government-linked organization that is trying to enforce a narrative on Ukraine while seeking to discredit dissenting views.

The organization has accused Consortium News, begun in 1995 by former Associated Press investigative reporter Robert Parry, of publishing “false content” on Ukraine.

BY Joe Lauria

It calls “false” essential facts about Ukraine that have been suppressed in mainstream media: 1) that there was a U.S.-backed coup in 2014 and 2) that neo-Nazism is a significant force in Ukraine. Reporting crucial information left out of corporate media is Consortium News‘ essential mission.

But NewsGuard considers these facts to be “myths” and is demanding Consortium News “correct” these “errors.”

... ETC...

SO WHAT ABOUT SWISSINFO?

Switzerland’s neutrality has not prevented it from becoming the target of fake news and propaganda from Moscow, reports show. An explainer.https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/swiss-diplomacy/how-switzerland-is-caught-up-in-russias-propaganda-machine/88785511?

.... NewsGuard documented at least ten false claims worldwide feeding the idea that Zelensky and his family are misusing Western aid to buy luxury villas, resorts and jewellery.

Many of these claims went viral, spreading quickly across social media platforms and being shared by thousands or millions of users in a short time.

“Each claim contributed to making the next one more believable, slowly but surely pushing the narrative further and contributing to the erosion of international support for Ukraine.

Among the goods Zelensky and his family were accused of buying were Sting’s Italian winery in Tuscany, the German villa of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, and a luxury ski resort in the French Alps, Labbe says.

Russia’s narrative also positions it in the ideological war against the West and what it considers Western values.

ETC....

=======================

HERE WE HAVE SOLID INFORMATION THAT ZELENSKY IS MORE CROOKED AND A WORSE COMEDIAN THAN THE JOKER IN BATMAN...

Revealed: ‘anti-oligarch’ Ukrainian president’s offshore connections

Volodymyr Zelenskiy has railed against politicians hiding wealth offshore but failed to disclose links to BVI firm

It was a storyline that in earlier times would have seemed impossible. For four years, the actor and comedian Volodymyr Zelenskiy entertained TV audiences in Ukraine with his starring role in the sitcom Servant of the People. Zelenskiy played a teacher who, outraged by his country’s chronic corruption, successfully runs for president. In 2019, Zelenskiy made fiction real when he contested Ukraine’s actual presidential election and won.

On the campaign trail, Zelenskiy pledged to clean up Ukraine’s oligarch-dominated ruling system. And he railed against politicians such as the wealthy incumbent Petro Poroshenko who hid their assets offshore. The message worked. Zelenskiy won 73% of the vote and now sits in a cavernous office in the capital, Kyiv, decorated with gilded stucco ceilings. Last month, he held talks with Joe Biden in the Oval Office.

The Pandora papers, leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with the Guardian as part of a global investigation however, suggest Zelenskiy is rather similar to his predecessors.

The leaked documents suggest he had – or has – a previously undisclosed stake in an offshore company, which he appears to have secretly transferred to a friend weeks before winning the presidential vote.

Zelenskiy has not commented on the claim despite extensive attempts by the Guardian and its media partners to reach him. His spokesperson Sergiy Nikiforov messaged: “Won’t be an answer.”

The files reveal Zelenskiy participated in a sprawling network of offshore companies, co-owned with his longtime friends and TV business partners. They include Serhiy Shefir, who produced Zelensky’s hit shows, and Shefir’s older brother, Borys, who wrote the scripts. Another member of the consortium is Ivan Bakanov, a childhood friend. Bakanov was general director of Zelenskiy’s production studio, Kvartal 95.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/oct/03/revealed-anti-oligarch-ukrainian-president-offshore-connections-volodymyr-zelenskiy

========================

PRESENTLY, ZELENSKY HAS DISMANTLED THE (AMERICAN SET UP) CORRUPTION CHECKERS IN UKRAINE BECAUSE THEY WERE CONNECTING THE DOTS, AND MANY OF ZELENSKY'S FRIENDS HAD BEEN CAUGHT... THE NOOSE WAS CLOSING IN ON AGENT VOLODYMYR OF MI6... EVEN HIS MOST ARDENT SUPPORTER IN THE USA, LINDSAY GRAHAM WAS HORRIFIED THAT ZELENSKY DISMANTLED THE ONLY WAY THE USA COULD KEEP EVEN BARELY A SLEEPY EYE ON THEIR CASH... AND JOE BIDEN HAD BOTH EYES CLOSED....

I WAS GOING TO SAY THE SOONER ZELENSKY IS BOOTED OUT, THE... HELL, THE PROBLEM IS THAT HIS MOST POPULAR REPLACEMENT IS ZALUZHNY... WHO IS MORE NAZI THAN ZELENSKY... FROM RT:

Retired Ukrainian General Valery Zaluzhny, widely seen as a potential successor to Vladimir Zelensky, has called for education programs that highlight members of the neo-Nazi Azov military unit as role models.

As Ukraine’s former top military commander and now ambassador to the UK, Zaluzhny is considered one of the country’s most popular public figures. Polls suggest he would likely defeat Zelensky if presidential elections were held, and Western governments are reportedly courting him as a possible future leader.

In an interview published on Saturday Zaluzhny praised the Soviet Union’s approach to memorializing historic figures and suggested Ukraine adopt a similar model using fighters with the controversial regiment – which is accused of war crimes and recognized as a bastion of militarized neo-Nazism – as examples of proper behavior.

“It’s very important for the military-patriotic education to know who did what and what came out of it,”Zaluzhny said. “Soviet propaganda did it right. I once argued with NATO specialists, telling them we, members of the military who grew up in this territory, put great importance into [historic connections].”

Ukraine, he added, should “set a goal of what it wants from its children in 10 years,” arguing that promoting Azov’s “heroism” would be beneficial.

Formed from members of radical Ukrainian nationalist groups, Azov was integrated into the National Guard in 2014 and since then has grown more influential and powerful. Before the escalation of the conflict with Russia in 2022, even Western observers described the unit as a hotbed of extremism and neo-Nazism that attracted white supremacist sympathizers across Europe.

In 2018, the US Congress barred funding for Azov over human rights concerns, but the restriction was lifted in 2024 after the group rebranded and claimed to have abandoned its neo-Nazi roots.

Russia designates Azov a terrorist organization and has accused its members of committing atrocities during hostilities. Moscow has identified “de-Nazification” – reducing the influence of radical nationalist ideology in Ukrainian politics – as one of its key goals in the conflict.

READ MORE: Zelensky rating slumps – pollAs of March, Russia’s Investigative Committee reported successful prosecutions against 145 members of Azov on charges including breach of rules of war, mistreatment of prisoners of war and civilians, and murder.

https://www.rt.com/russia/623535-zaluzhny-azov-role-models/

=======================

SO READ CAREFULLY ABOUT SWISS "NEUTRALITY" WHICH IS TRYING HARD TO EMBRACE NATO...

=======================

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.