Search

Recent comments

- criminal jew....

1 hour 1 min ago - gestapo....

1 hour 36 min ago - criminal....

1 hour 41 min ago - intensity....

7 hours 7 min ago - adaptation....

7 hours 47 min ago - bloody op.....

18 hours 40 min ago - avoiding biffo....

1 day 31 min ago - leak....

1 day 2 hours ago - trump's women....

1 day 6 hours ago - CIA control....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

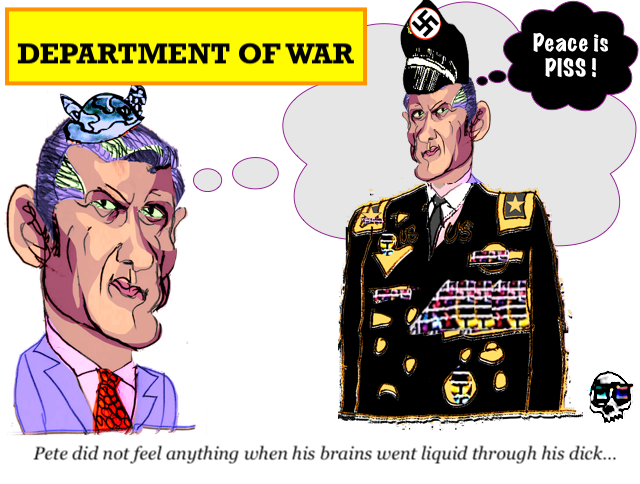

improving the business of war: mother courage should be impressed....

“The defense acquisition system as you know it is dead,” Secretary of War Pete Hegseth said in a major speech delivered to industry representatives Nov. 7 at the National War College in Washington, D.C.

In the more than hour-long speech, the secretary of war promised to upend the Defense Department’s acquisition system, told members of the industrial base to do their part to speed up deliveries or leave the business and vowed to reform the foreign military sales system.

“This is not a speech. This is not a fire and forget. This is the beginning of an unrelenting onslaught to change the way we do business and to change the way the bureaucracy responds,” he said.

One particular source of inefficiency, Hegseth said, has been the Joint Capabilities and Integration Development System process, or JCIDS, which defined acquisition requirements for defense programs.

The Defense Department is cancelling JCIDS, “which moved at the speed of paperwork, not war,” he said. The Joint Requirements Oversight Council will be reoriented to start identifying “joint operational problems,” which “will drive the priorities for the entire department.

In JCIDS’ place will come three new entities, he said: the Requirements and Resourcing Alignment Board that will “tie money directly to” the top warfighting priorities; the Mission Engineering and Integration Activity to rapidly experiment and prototype solutions; and the Joint Acceleration Reserve, a funding pool set aside to quickly field promising capabilities.

The military services have also been directed to reform their own requirements processes to cut red tape, engage industry earlier and align their priorities with the new joint system, Hegseth said.

With these changes to requirements development, “speed replaces process, money follows need, joint problems drive action, experimentation accelerates delivery and the services move faster and smarter,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Defense Acquisition System is being rebranded as the Warfighting Acquisition System, which will involve more than just a name change, Hegseth said.

The new system will “dramatically shorten timelines, improve and expand the defense industrial base, boost competition and empower acquisition officials to take risks and make trade-offs,” he said.

The core principle of the acquisition transformation is to “place accountable decision-makers as close as possible to the program execution, eliminate the layers of bureaucracy that hinder them and then empower them with the authorities and flexibility to drive timely delivery,” he said.

To accomplish this, the Defense Department’s program executive officers will become portfolio acquisition executives, or PAEs.

These executives “will be the single accountable official for portfolio outcomes and have the authority to act without running through months or even years of approval chains — and they'll be held accountable to deliver results,” Hegseth said.

PAEs will have the authority to make decisions on cost, schedule and performance and to shift funding within their portfolios to accelerate higher warfighting priorities if a program is faltering or to pivot if new or more promising technologies emerge, he said.

Within 180 days, portfolio acquisition executives will be receiving new guidance on how to implement additional “game-changing practices,” Hegseth said.

The Pentagon will: establish adaptable test approaches that enable rapid certification; evaluate multi-track acquisition strategies to allow third-party surge manufacturing capacity; maintain a standard to carry at least two qualified sources through initial production; and establish module-level competition by using modular open systems approaches.

The Defense Department will also mandate portfolio scorecards to measure “what truly matters — the time it takes to put weapons in the hands of our men and women who use” them, Hegseth said.

A PAE's "performance will be judged not on mindless compliance with thousands of pages of regulations, but on mission outcomes. ... If the mission is not successful, there will be real consequences," Hegseth said.

To ensure accountability, portfolio acquisition executives' tenures will be longer than current PEO service times, he added. They will have four-year appointments, with possible two-year extensions, he said.

Jerry McGinn, director of the Center for the Industrial Base at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said transitioning from a defense-oriented perspective to a wartime one is “exactly what we need.”

The shift means the department must take more risk in a way that isn’t reckless, emphasizing a focus on speed and scale, he said.

“That means DoD has be [a] better customer and better demand signals, change incentive structures to get industry to invest, and then it's up to industry to respond, whether they're traditional, non-traditional, new entrants, tech, commercial or just defense-oriented,” McGinn told National Defense in a phone interview.

The big focus of this transformation introduced by Hegseth is reducing bureaucracy in the acquisitions process, as well as getting capability into the hands of warfighters faster, developed and delivered at speed and scale. Eliminating the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System and replacing program executive officers with portfolio acquisition executives are “all about that,” McGinn said.

“It's about giving the PAEs the ability to make trades within portfolios. And that means if programs aren't working, to put more effort into it,” as well as being able to “surge funding where need be to help accomplish the mission, being closer to the warfighter and having the accountability to be able, and the ability and the accountability to be able to be responsible for delivery,” he said.

Additionally, Hegseth said the Defense Department will prioritize commercial solutions to deliver capability to warfighters faster. “We will harness more of America's innovative companies to focus their talent and their technologies on our toughest national security problems. We're leaving too much on the cutting room floor.”

The department is also establishing the Wartime Production Unit. Born out of the existing Joint Production Accelerator Cell, the new unit will manage and execute the direct support of urgent acquisition production priorities, bringing together manufacturing and supply chain experts from within the Pentagon and industry to surge manufacturing capacity and deliver weapons at speed, the department’s Acquisition Transformation Strategy document released Nov. 7 stated.

This includes encouraging creative investment strategies, expanding the defense industrial base with new entrants and incentivizing companies to spend their own capital on increasing production capacity, he added. The Pentagon will work with Congress “to make the department a more predictable partner for industry” through multi-year procurements and stable funding mechanisms.

Hegseth didn’t mince words when it came to his expectations of defense contractors, singling out the “primes” in his speech.

While the Pentagon has not always been helpful communicating its requirements to industry, he admitted.

“The department's perverse process has, in turn, fostered a culture in today's defense industrial base that makes it unlike any other American market, uniquely tailored to the Pentagon in the worst way. Unstable demand signals, uncertain projections and a volatile customer base [have] caused the defense industry to … adopt … the same entrenched risk averse and lethargic culture that we have in government,” he said.

Nevertheless, “these large defense primes need to change the focus on speed and volume and invest their own capital to get there,” he said.

For its part, the Pentagon will publish new guidance to ensure that there are clear incentives for contractors to deliver on time, increase production capacity and have the demand signal needed to attract private investment, he said. It will encourage new entrants to join the defense industrial base, he said.

He declared an end to monopolies in the defense business and said he wanted two producers to manufacture platforms when they were ready for production.

He did not mention the Defense Production Act by name but said: “Industry must use capital expenditures to upgrade facilities, upskill their workforce and expand capacity. If they don't, we are prepared to fully employ and leverage the many authorities provided to the president which ensure that the department can secure from industry anything and everything that is required to fight and win our nation's wars.”

The Pentagon has nothing against profits, but if companies don’t reinvest in increased capacity, “those big ones will fade away,” he said.

“Either you — our companies, our industries, our defense industrial base — deliver, or we fail. It is literally life or death,” he said.

Hegseth also promised to reform the foreign military sales system. “We didn't break it, but we're going to fix it,” he said.

Weapon sales to allies and partners are part of “our strategic vision on the global landscape. Burden sharing has been a key pillar of President Trump's and the Department of War's agenda, and to accomplish this, our allies and partners must be armed with the best and most interoperable weapons systems in the world,” he said.

The reforms will move ahead with the cooperation of the Departments of Commerce and State, which are also involved in approving weapons sales, he said.

The key will be “aligning sales with our efforts to revitalize the defense industrial base,” he said. “We've worked to bake exportability into the acquisition lifecycle from the very beginning, and we're investing heavily in making that a reality.”

Inside the Pentagon, foreign military sales approvals carried out by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency and the Defense Technology Security Administration will be moved from the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy to the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment.

That will put the whole lifecycle of weapon procurement for foreign partners — from basic research to the sustainment of the products after they have been delivered — under one roof, he said.

“Starting today, we will now manage our defense sales enterprise with a single integrated vision, from initial planning to contract execution to delivery,” he said.

He also wanted the defense industry to take the profits garnered from such sales and to reinvest them in their industrial capacity. He promised more announcements about FMS reforms “in the months ahead.”

Two pieces of bipartisan legislation support the speed-focused effort, Hegseth noted: The Fostering Reform and Government Efficiency in Defense Act, introduced in the Senate in December 2024, and the Streamlining Procurement for Effective Execution and Delivery Act, introduced in the House of Representatives in June.

“Many of the changes we're implementing today are the direct result of those congressional engagements,” Hegseth said. “And we look forward to continuing this vital collaboration as we transform the department.”

In a statement released following Hegseth’s comments, Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, described Hegseth’s recognition of the Fostering Reform and Government Efficiency in Defense Act as “a pivotal moment for our national security.”

“These reforms will be a game changer for U.S. defense, ensuring our military has the advanced equipment needed to deter adversaries like China and Russia,” Wicker said.

Speed-focused priorities will be implemented in the next National Defense Authorization Act, Wicker added. The NDAA for fiscal year 2026 is currently in the process of being passed, with a final vote expected in the coming months.

Implementing the priorities will require “close cooperation between Congress and the Pentagon,” added House Armed Services Committee Chair Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Ala., in a statement to National Defense via email.

“I’m grateful that the secretary is a willing and enthusiastic partner in our efforts to reform it,” Rogers said. “He shares the goal we set out in the SPEED Act — fundamentally reforming acquisition so it delivers our warfighters what they need, when they need it.”

The next National Defense Authorization Act — paired with the Pentagon’s reforms — “mark a generational transition in our processes for setting requirements and acquiring equipment and weapons,” Rep. Robert Wittman, R-Va., a member of the House Armed Services Committee, told National Defense via email.

Wittman added that the defense industrial base must be prepared for war, as the United States is “in the most dangerous security environment since the 1940s.”

The House Armed Services Committee “has been focused on defense acquisition reform for almost two years,” making it encouraging to see Hegseth’s engagement with the issue, said Rep. Donald Norcross, D-N.J., another committee member.

Amid the intensified focus on speed, “we cannot lose sight of the importance of also delivering better capabilities at a reasonable cost to American taxpayers," Norcross said in a statement to National Defense.

Sen. Tim Sheehy, R-Mont., a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said the overhaul “will go a long way” when it comes to the nation meeting the demands of modern warfare.

“After decades of bureaucratic sclerosis, reforming the way we develop, produce and deploy weapons is not an option,” Sheehy told National Defense in an email. “It’s an imperative.”

McGinn said while Hegseth laid out a “great” framework, the key will be implementation and resourcing, “It's not the first time they've tried do acquisition reform.”

“The good news is this is being done in the first year of the administration. So, they've got three years to go after all these different strands.”

Reporting by Josh Luckenbaugh, Stew Magnuson, Allyson Park and Tabitha Reeves

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO:

Mother Courage and Her Children, play by Bertolt Brecht, written in German as Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder: Eine Chronik aus dem Dreissigjährigen Krieg, produced in 1941 and published in 1949. The work, composed of 12 scenes, is a chronicle play of the Thirty Years’ War and is based on the picaresque novel Simplicissimus (1669) by Hans Jacob Christoph von Grimmelshausen. In 1949 Brecht staged Mother Courage, with music by Paul Dessau, in East Berlin. Brecht’s wife, Helene Weigel, performed the title role. This production led to the formation of the Brecht’s own theatre company, the influential Berliner Ensemble.

The plot revolves around a woman who depends on war for her personal survival and who is nicknamed Mother Courage for her coolness in safeguarding her merchandise under enemy fire. The deaths of her three children, one by one, do not interrupt her profiteering.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mother-Courage-and-Her-Children

- By Gus Leonisky at 9 Nov 2025 - 7:20am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

sunset and sunrise.....

The West’s Three Options in a Multipolar World

The sunset of Western hegemony does not entail the disappearance of the West.

BY Peter Slezkine

According to the “global majority” (as the Russians call it), the sun is finally setting on the West. After 500 years of dominance, the West is showing signs of relative decline across almost every dimension. A protracted period of historical anomaly is passing, and the world is entering an age defined by a reassertion of sovereign interests and a resurgence of ancient civilizations.

At a certain remove, this image seems a reasonable enough representation of new realities. But as a roadmap for navigating international politics, it is far too rough a sketch.

First, “decline” does not mean “displacement.” The West may lose its power to rule by diktat. Its institutions, culture, and moral fashions may lose their charm. But we will continue to live in a profoundly modern and globalized world of Western origin. Our systems of education and science, our forms of government, our legal and financial mechanisms, and our built environment will continue to rest on a Western foundation. A weakening West is unlikely to find itself in a post-Western world.

Second, “the West” is a fluid concept. It has shifted shape before, and may reconfigure itself once more. Before considering what the West might become going forward, we need to figure out what sort of power is passing from the scene.

The history of Western hegemony can be split into two separate eras. Until 1945, the West may have ruled the world, but it did so as a collection of competing states rather than a single entity. In fact, it was precisely competition within a fractured West that provided a major impetus for outward expansion.

After 1945, the picture changed dramatically. For the first time, a politically united West emerged under the American aegis. But while American officials consolidated the West, they did not organize U.S. foreign policy around it. Instead, they claimed leadership of the “free world,” which they defined negatively as the entire “non-communist world.” The Western core of the postwar American order was thus doubly effaced: It was identified with a lowest-common-denominator global liberalism that depended, in turn, on the presumption of an existential external threat for any semblance of internal coherence.

The collapse of the Soviet Union did not change this underlying logic. The West began to refer to itself as “the international community,” and when liberal democracy failed to spread to the ends of the earth, it returned to the business of defending the “free world,” first against “radical Islam” and then against its familiar Cold War foes—Russia and China.

The Biden administration represented both the climax and culmination of this foreign policy approach. Biden entered the White House declaring a global divide between democracy and autocracy and sought to create linkages between Europe and Asia as part of a global alliance against Russia and China. But the result, especially after the start of the war in Ukraine, was not unity of a global “liberal order,” but a rapidly growing and increasingly obvious gap between the West’s universalist claims and its limited reach. Europe moved in lockstep; the rest of the world mostly went its own way. Ultimately, the “liberal order” was rejected not only by the non-West, but also by the American electorate, which last year voted for America First for a second time.

So where does this leave the West? I see three paths forward. The first is a limited liberal restoration. One can imagine European elites beating back domestic opposition, outlasting Trump, and finding a champion in the Democratic Party, which promises a partial return to the status quo ante. The Atlanticist infrastructure is strong, and inertia is a powerful force. But even in the case of a post-Trump restoration, popular antipathy to the liberal internationalist program will result in considerable counterpressure, and resource constraints will continue to limit Western reach.

Another possibility is a radical retrenchment, understood as an abandonment of empire in favor of the nation. Politically, such a move would be broadly popular. Promising to put the interests of American citizens first has obvious appeal to the American voter. Calls to reprioritize the nation also resonate across much of Europe. Nationalism naturally fits the frame of democratic politics. It also represents the seemingly self-evident alternative to the previously dominant frame of liberal universalism. A more nationalist policy is the basic premise of MAGA, and a growing number of right-wing “influencers” are actively pushing this agenda. The neutering of USAID, Radio Free Europe, and the National Endowment for Democracy represents a substantial step in this direction. A new national defense strategy that prioritizes homeland security may force a further shift away from a foreign policy dedicated to leadership of the “liberal order.”

But existing entanglements will be difficult to undo. Atlanticist elites remain entrenched in key positions inside and outside of government, and complex structures like NATO and the European Union may endure, even if populist parties gain power across the West. Just as importantly, nationalist leaders in the West seem to understand that the single-minded pursuit of national sovereignty will produce countries too weak to possess true autonomy on the international stage. If the United States withdraws to the Western Hemisphere, then the project of European integration will almost assuredly collapse. And in a world of massive great powers, individual European nations will no longer be able to punch above their weight (as they did before 1945). Although nationalist parties in Europe may oppose the transatlantic structures of the “liberal order,” they tend not to envision a total split from the United States. The United States, meanwhile, is large (and secure) enough to maintain a relatively strong position in the international system even if it abandons empire entirely. But most members of the MAGAverse do not envision a retreat so complete. At minimum, they tend to imagine maintaining U.S. dominance from Panama to Greenland.

At most, they would prefer to keep control of the entire West. The third and final option, then, is a new transatlantic consolidation that replaces a liberal universalist logic with a self-consciously civilizational frame, with the United States as the acknowledged metropole and Europe as a privileged periphery. If American leadership of the liberal order does represent a net resource drain (as Trump and his allies claim), then the new transatlantic arrangement would reverse the flow. At the same time, it would afford European nations membership in a club with sufficient population and resources to compete in the global arena. Finally, membership in the Western club would not require the sacrifice of national identity at the altar of global liberalism. In fact, it would require the reassertion of national identity within a pan-Western frame at the expense of policies favoring limitless immigration and never-ending expansion.

The construction of a self-consciously “collective West” would constitute an embrace of multipolarity and an attempt to create the most powerful pole in the system. It would also probably result in a reorientation—moving away from the tanks-and-troops logic created by the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, and toward a focus on tech and trade more suited to competition with China. Vice President J.D. Vance’s speech at the AI Summit in Paris, his broadside against the Atlanticists at the Munich Security Conference, and President Donald Trump’s recent speech at the United Nations have all pushed Europe to reorganize along these lines. Efforts to burden-shift in NATO, along with recent trade deals with Britain and the EU, represent practical steps in this direction.

The problem is that the West has spent decades dissolving itself within the liberal order and has little civilizational content to fall back on. The Western canon has been mostly destroyed in higher education, and religious practice has been on the wane throughout the West. Christianity is still a powerful force in American politics (as we saw at the revival-style memorial for Charlie Kirk), but the West can no longer claim to be Christendom. In the current moment, the idea of the West mainly appeals to a small number of influential New Right intellectuals, and to geopoliticians and tech titans who desire scale (but realize that the globe is too big to swallow).

There are obstacles on all three paths. And they are not, in fact, alternatives. The likeliest outcome is probably a combination of all three. Bureaucratic inertia favors the first option, limited liberal restoration; the logic of domestic politics favors the second, nationalist retrenchment; and geopolitical imperatives favor the third, the creation of a real “collective West.”

In any event, the United States is poised to maintain a favorable position in a multipolar world. The legacy institutions of international liberalism have largely lost their purpose, but retain residual power (which, ironically, the U.S. can leverage most effectively against other members of the “liberal order”). Going forward, the Trump administration should continue to push for a reconfiguration of the transatlantic relationship as a self-consciously Western coalition united by a common approach to trade, technology, and resource management. And if Europe fails to accept its new role, or play it well, then Washington can cut bait and retrench to prepared positions in the Western Hemisphere.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-wests-three-options-in-a-multipolar-world/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

IT'S TIME TO SMOOTH THE CORNERS IN OUR RELATIONSHIPS....

piss in their heads....

US Secretary of War Pete Hegseth has announced a military operation against “narcoterrorists” amid ongoing tensions with Venezuela and strikes on alleged cartel vessels.

“Today, I’m announcing Operation SOUTHERN SPEAR,” Hegseth wrote on X Thursday.

“Led by Joint Task Force Southern Spear and SOUTHCOM, this mission defends our homeland, removes narco-terrorists from our hemisphere, and secures our homeland from the drugs that are killing our people. The Western Hemisphere is America’s neighborhood – and we will protect it,” he wrote.

Hegseth did not specify whether the operation would expand on the strikes against alleged cartel vessels in international waters of the Caribbean Sea. Since September, the US has destroyed at least 20 boats, killing 80 people.

Citing unnamed US officials, CNN reported that the US Southern Command briefed President Donald Trump on target options inside Venezuela as part of Operation Southern Spear. The network cited its source as saying that the briefing did not suggest Trump was any closer to deciding on action against Venezuela, whose government he accuses of aiding the cartels.

READ MORE: Pentagon top brass offer Trump new military options for Venezuela – CBSThe US imposed sweeping sanctions on Caracas during Trump’s first term and placed a $50 million bounty on Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. The US dispatched a naval armada, including the aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford, to the region, while Venezuela put its army on alert.

Maduro has denied any involvement in drug trafficking and warned the US against starting a “crazy war.”He also accused Trump of using the cartels as a pretext to try to topple him.

https://www.rt.com/news/627771-us-operation-against-narcoterrorists/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.