Search

Recent comments

- cow bells....

12 hours 55 min ago - exiled....

17 hours 57 min ago - whitewashing a turd....

18 hours 56 min ago - send him back....

20 hours 26 min ago - the original...

22 hours 14 min ago - NZ leaks....

1 day 8 hours ago - help?....

1 day 9 hours ago - maps....

1 day 9 hours ago - bastards...

1 day 15 hours ago - narcissist.....

1 day 16 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

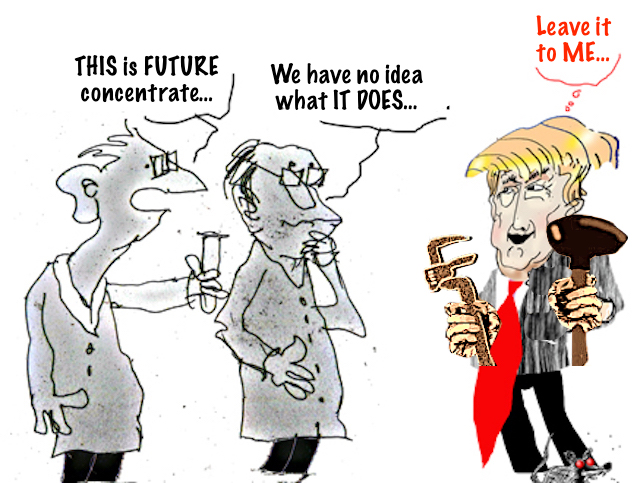

F for future or for failure.....

In 1971, Time magazine decided that it might do a friendly cover story on newly installed Liberal prime minister, Billy McMahon, and asked for co-operation from his media office. The office asked that questions be submitted in writing. This was not from mistrust of Time – indeed the office was deeply conscious of what Jane Austen would call the magazine’s condescension in so honouring an Asian backwater. It was from mistrust of Billy, who was capable of almost any media stuff-up.

Steering without a compass or a map By Jack Waterford

Time journalist John Shaw went through the pre-submitted questions, but for his final query asked one that was not on the script: it was a lollypop, set to be hit to the Boundary: “What are your thoughts on the future of Australia?”

“McMahon, confronted with the unexpected, was nonplussed,” Time reported. “McMahon shuffled rapidly through his paper, he found no brief on the future, no position paper files under F, no memorandum on destiny. He said, ‘I’ll have to send you a note on that’, but he never did.”

That was a long time ago, but it could have happened yesterday. To most of the political leaders of the past decade or so.

The article commented that “today the US is engaged in extricating itself from Indochina, and is unlikely to make new commitments in South East Asia for some time. Yet the Soviet Union, China and Japan are increasing their influence in the oceans that bound Australia.

“Clearly the Australians are being challenged to find a new role for themselves in the Pacific. But the response of their leadership has been less than dynamic. Indeed, some critics grumble that Australia’s political leadership is so mediocre that every rosy prediction about the national destiny must be qualified.”

Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, John Howard, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull would not have been flatfooted like Billy (later Sir William) McMahon. The quality of the words might have varied – and, perhaps only one or two would have been memorable. But the howls of laughter after McMahon’s response seem to have made nearly all subsequent prime ministers and political leaders elsewhere cautious about getting involved in what President George Bush senior once called “the vision thing”.

People kept telling Bush he needed to articulate a vision. He was rated as competent and clear thinking, but boring and unable to galvanise or mobilise passion and emotions. Bill Clinton beat him.

In writing about politics, including from the time of Billy McMahon, I have always paid a lot of attention to the vision thing. I accept that most people enter politics with a desire to do good and achieve good outcomes consistent with broader philosophical principles and personal experiences. I am, of course, also interested in those with whom they identify, but my initial judgments, and opinions, are not based on their party affiliations.

We accept you meant well. But how does your action square with your proclaimed values and the reason you said you were here?

Politicians spend most of their time dealing with mundane matters, not trudging up to the light on the hill. It is still nice to understand where they think they came from, and what they think they can achieve. Of course, the new member will usually not have much direct influence, but will have been taught by the pre-selection struggles something about the wheedling, trading, and debating involved in wooing someone to their side.

Even the pure-minded will find that a lot of politics is transactional, and one must give to earn credit with others. Binding party commitments or tactical considerations will force the ambitious into short-term action or statements at complete odds with their announced philosophy. Often, because of party loyalties, observers will not see background lobbying, arguments or deals that would show that principle was not lightly discarded (or sold in some higher cause) and that the politician was quite conscious that they would be called a hypocrite when all that had happened was that their argument could not prevail over the majority view of their colleagues.

The position of party leaders is different. They are, by definition, people chosen by their own party to devise and enunciate policies, and to explain and promote them in the parliament, in the party, and among the public. If they have the vision thing, they are also explaining priorities and their ultimate aims. The shorthand for this might be where they expect to be, carrying out their policies, after 10 years, after five years, and at the end of their three-year terms. They must announce the destination. They must announce their road map. Voters may well understand that the plan will have to be amended over time, but they want to feel that the party is going in the direction promised. If for good reasons the destination or route changes, good leaders would have prepared voters for the change, and explained it over and over again. Some may feel betrayed. Some may have mentally invested a policy with moral qualities. Some may think that a promise can never be dropped. Actually voters will often give credit for responding to circumstance. If, that is, they feel they have been warned, consulted and given reasons and explanations.

Parties are made up of factions, some at bitter odds with each other. Party leaders must weld together different strands of thought so that the party is united around agreed themes. At least after the compromises have been made, and often before, they must take every opportunity to advance the policy, to take on those opposed to it, and to explain and defend repeatedly. As Paul Keating said, it is only when one is sick of the repetition that one might be moving towards first base.

Leaders must be alert to marketing opportunities and nimble enough to adapt to events that change the nature of the argument. They must also accept that sometimes carefully researched and articulated policies will fail to get traction with the public, be outflanked by some tactic from the other side, or lose the potency of its organising idea by trickery, distractions or misrepresentation. One must take events as one finds them, and sometimes decide that a plan is not for the moment and should be shelved. But the true leader will usually retain the idea for a moment that can be revived, just as, for example, it always seemed that John Howard had a permanent agenda on industrial relations reform, but the patience to wait, after defeat, to revive it and try again.

Howard, a slippery and dogged leader with no great charisma, is a study of many types of effective leadership, in part because he learnt from early failures and pratfalls. After a term in which his very credibility and believability were in question because of events such as the Children Overboard affair, Howard declared that the 2004 election was about “trust”. He did not really mean that he wanted voters to agree that his statements had been credible; they wouldn’t have done so. But he was arguing that then Labor leader, Mark Latham, was a loose cannon, unpredictable, erratic and unreliable. One could not trust him to be the sort of leader needed. Voters agreed with Howard’s attack, and he was re-elected after having been behind in opinion polls.

Howard, again, was entirely pragmatic and capable of a complete turnaround if a policy became unpopular, not worth defending. He demonstrated how an effective leader continually reintroduces themselves to the electorate and persuades voters to see the political problem as they see it.

Voters are usually aware of the news and can recognise propaganda when they see it. Leaders want the public to consider them as reliable commentators to be treated with respect. Being frank with voters can secure brownie points, as former Queensland Premier, Peter Beattie, did. Beattie would stress and explain the good intentions which turned out to be impractical. Or frustrated by events that could not have been predicted. Or sabotaged by the bad faith of some of the players. Voters understand failure in their own workplaces, organisations and community groups. They may not expect failure, but are more interested in the follow-up. Politicians in denial get into more trouble than those who hold post-mortems and are honest with voters.

Painting pictures of a better future

The problem for leaders such as Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton begins with the fact that most voters do not feel they know them. They do not know their strength of character. They do not understand their basic values, or what they stand for. Dutton is far better understood than Albanese, but not necessarily in a way designed to attract votes. It’s not whether he is on the public wavelength on refugee policy, immigration numbers, or the place of Indigenous people in Australian society. Labor’s policy cowardice and refusal to engage may mean that Dutton is closer to public opinion. But sustained attacks on Dutton, going back to Morrison’s days, portray him as a nasty and mean piece of work. He need not be popular. Nor King of the kids. Dutton has projected images of his likely style. But, with or without nuclear power, he has not inspired voters with an understanding of how he would govern or what his policies really are. His negativity, lack of charisma and association with the systemic misgovernment in the Morrison era weaken his position.

Albanese cannot base an election campaign on his record in government. Nor can he do it with more Medicare or cost of living handouts. His record is disappointing, and most voters regard him as timid and ineffective, culpably afraid even of implementing clear party policy on matters such as gambling, Aboriginal advancement and tax reform. Labor’s survival depends on a focus on the future, one based on a vision, a destination and an embrace of the electorate. A complete change of personality for Albanese, particularly in communicating with voters and enlisting them in his campaigns. It will not be by policies and promises — or fetishes about carrying them out — that he can win the election.

People want to be led, but they want to know where they’re going. All the more so given the risk that these mediocre men might lead us over a cliff.

https://johnmenadue.com/steering-without-a-compass-or-a-map/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

HYPOCRISY ISN’T ONE OF THE TEN COMMANDMENTS SINS.

HENCE ITS POPULARITY IN THE ABRAHAMIC TRADITIONS…

PLEASE DO NOT BLAME RUSSIA IF WW3 STARTS. BLAME AMERICA.

- By Gus Leonisky at 7 Jan 2025 - 6:59am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

revisiting the future....

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

HYPOCRISY ISN’T ONE OF THE TEN COMMANDMENTS SINS.

HENCE ITS POPULARITY IN THE ABRAHAMIC TRADITIONS…

PLEASE DO NOT BLAME RUSSIA IF WW3 STARTS. BLAME AMERICA.