Search

Recent comments

- brainwashed tim....

1 hour 59 min ago - embezzlers.....

2 hours 5 min ago - epstein connect....

2 hours 16 min ago - 腐敗....

2 hours 35 min ago - multicultural....

2 hours 42 min ago - figurehead....

5 hours 50 min ago - jewish blood....

6 hours 49 min ago - tickled royals....

6 hours 56 min ago - cow bells....

20 hours 49 min ago - exiled....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

defending the world against itself.....

The Trump ascendancy has forced international economic issues and the future strategic outlook onto the Australian election agenda, even if they are at the margins.

This campaign — while dominated by domestic issues, notably the cost of living — is taking place against the background of an extraordinarily volatile external situation, with major implications for Australia’s future.

Politics with Michelle Grattan: Hugh White on what the next PM should tell Trump and defending Australia – without the US

To discuss these issues, we were joined on the podcast by Hugh White, emeritus professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University. White is one of Australia’s foremost thinkers on defence policy, China and the region. His long career includes serving as an adviser to then federal defence minister Kim Beazley.

White regards US President Donald Trump as a “revolutionary figure”:

I think Trump is a genuinely revolutionary character, and not just his impact on American domestic politics and economics, I also think he has a huge impact on global strategic affairs. And the reason for that is that he does have a fundamentally different view of America’s place in the world than that of what we might call a Washington establishment.

Donald Trump is really a kind of an old-fashioned isolationist. That is, he believes America’s strategic focus should be on the Western hemisphere […] For example, in Ukraine he’s happy to see Russia assert itself as a great power in Eastern Europe. In Asia, I think, despite his reputation as a China hawk on economic issues, he doesn’t have any problem with China asserting itself as a great power in East Asia. He’s for these other great powers to dominate their backyards, just the way he wants America to dominate its backyard in the Western hemisphere.

Yet White doesn’t believe either Labor or the Coalition is taking defence seriously in this election.

It’s not being treated as a real issue in the campaign, and that’s because both sides have determined that it won’t, and what underpins that is the absolutely rock-solid bipartisanship between the two of them on every significant issue. And I think that’s a very serious problem for Australia, because at a time when our strategic circumstances are changing dramatically […] neither side has any inclination to have a serious conversation about what that means, why it’s happening, what we should be doing about it,

A lot of the blame for that lies with the Labor Party, because it seems to me Labor’s political approach to the whole question of foreign affairs and defence for a very long time now has focused on minimising differences with the Coalition.

While White agrees Australia needs new submarines, and quickly, he doesn’t think they should be nuclear-powered, as promised under AUKUS. He thinks we should leave AUKUS.

We should have started building replacements for the [Collins-class submarine] around about 2010 or 2012. So we’re well over a decade late and I do think there’s a real risk that we’re going to lose our submarine capability altogether. But the way to solve that is not to push ahead spending billions and billions of dollars on a project which, even if it works, delivers the submarines we don’t need, and which is very unlikely to deliver any submarines at all.

We’re past looking for a perfect submarine. We just need to get any submarine at all so we can keep some capability running and then once we have that running, we need to have a really focused program. We need ministers to really tell Defence what to do, focus programs to develop a follow on to the Collins-class design, because that’s the design we already know best in the world and to start building a new class of evolved Collins.

After the 3 May election, when the next prime minister meets the US president to talk trade, defence and more, what should Anthony Albanese or Peter Dutton tell Trump? White says:

Trump is very hard to handle. I don’t think there’s any magic formula that an Australian prime minister can utter, which makes Trump into either a more acceptable, economic partner for Australia or a more reliable strategic partner for Australia, because the forces that are driving America out of Asia are much bigger than Donald Trump.

The most important thing an Australian political leader could say to Trump when he first meets him is, look, we understand where you’re coming from. We are happy to take responsibility for our own security. We don’t expect you to stay engaged in Asia to look after us in future. What we want you to do is to help us manage that transition as best we can and we’re prepared to pay for what we get.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TyfuZ2R5Dy8

- By Gus Leonisky at 16 Apr 2025 - 12:57pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

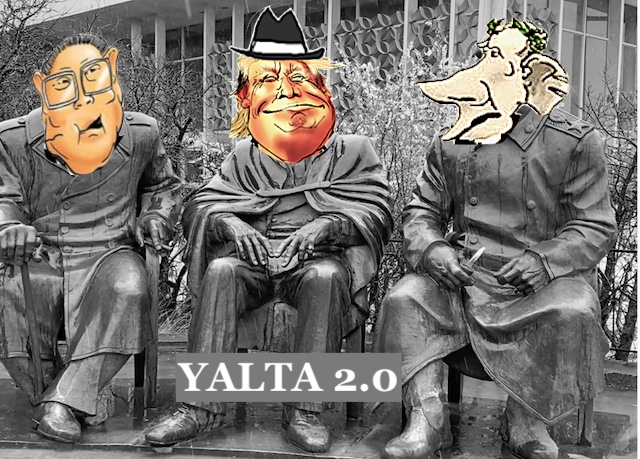

yalta....

Combined might of Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill saved the world. Can we repeat the recipe?

How three men in Yalta decided the fate of the planet – and why it still matters

By Roman Shumov

Discussions about building a new global order have become increasingly frequent and urgent. Many argue that the international system established after World War II can no longer effectively prevent the tragedies and conflicts we witness today. But how exactly was this fragile system created in the first place?

Much like today, Europe became a brutal battleground in the mid-20th century. At that crucial turning point, Moscow and the Western powers were forced into negotiations, despite mutual distrust and seemingly insurmountable differences. They had little choice but to come together, stop the bloodshed, and create a new framework for global security. These uneasy compromises and agreements fundamentally shaped today’s world.

Unlikely alliesBefore WWII, the idea of an alliance between the Western powers and the Soviet Union seemed unimaginable. Western leaders dismissed Soviet attempts to contain Adolf Hitler’s aggressive ambitions, viewing the USSR as neither strong nor trustworthy enough to be a partner. Miscalculations and mutual suspicion drove both the West and the Soviets to separately strike deals with Hitler – first the Western powers in 1938, then the Soviet Union in 1939. These ill-fated decisions allowed Nazi Germany to destroy Czechoslovakia and conquer Europe step by step.

Everything changed in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, forcing Moscow into an alliance with Britain. Few believed the Soviet Union could withstand Germany’s powerful military, which had quickly defeated Western armies. Yet, Soviet forces fiercely resisted. By December, the Soviets launched a counteroffensive near Moscow, halting the German advance. Days later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, drawing the United States fully into the war. The Anti-Hitler Coalition was now complete, united by the common goal of defeating Nazi Germany.

Despite military cooperation, deep tensions remained among the Allies, especially over territorial ambitions. Between 1939 and 1940, the USSR reclaimed territories formerly belonging to the Russian Empire – regions in eastern Poland, parts of Finland, Bessarabia (today’s Moldova), and the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Although Poland and other affected nations protested, wartime priorities overshadowed these concerns. Moreover, the Allies were willing to sacrifice national sovereignty in strategically important regions – such as Iran, jointly occupied by Britain and the USSR – to ensure vital supply routes.

Strategic disputes and shiftsStalin repeatedly demanded that the Allies open a second front in Europe to relieve pressure on Soviet forces, which were sustaining tremendous losses. Frustrated by Allied focus on North Africa and Italy rather than a direct assault against Germany, Stalin nonetheless accepted substantial military aid via Lend-Lease and benefited indirectly from relentless Allied bombing of German industry.

In 1942, Allied leaders debated whether to prioritize defeating Germany in Europe or Japan in the Pacific. Winston Churchill insisted that crushing Germany would inevitably lead to Japan’s defeat. Despite America’s primary focus on the Pacific, strategic logic eventually favored Europe.

Yet the Allied path into Europe proved difficult. The British favored a strategy of encircling Germany – first via North Africa and Italy – before invading France from the north. The disastrous Dieppe raid underscored the challenge of invading France directly. Consequently, operations began in North Africa in 1942 and Italy in 1943, irritating Stalin, who criticized these campaigns as secondary. While Allied bombing weakened Germany’s war industry, Stalin continued pressing for immediate help on the Eastern Front.

In 1943, decisive Allied victories at Stalingrad and in North Africa turned the tide. Leaders now demanded Germany’s unconditional surrender, hardening German resistance but solidifying Allied resolve. Victories continued as the Soviets advanced decisively through Ukraine and Poland, while Western forces moved slowly through Italy.

In November 1943, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met in Tehran. The conference proved crucially productive: leaders finalized plans for the Normandy invasion to open a western front, secured Soviet commitment to join the war against Japan after Germany’s defeat, and debated Germany’s future. Churchill and Roosevelt proposed dividing Germany into several states, but Stalin insisted it remain unified.

Significant progress was also made regarding Poland. Stalin gained acceptance for the Soviet annexation of eastern Polish territories, compensating Poland with land in eastern Germany and parts of East Prussia. Most importantly, Tehran set the stage for establishing the United Nations as a mechanism to prevent future global conflicts.

Yalta and the new world orderIn February 1945, world leaders convened at the Yalta Conference in Crimea to determine the shape of the post-war world. Although Nazi Germany was still resisting fiercely, it was evident their defeat was inevitable, prompting discussions about the future global order.

The Yalta summit represented the high point of an unlikely and uneasy alliance between vastly different countries, yet its outcome provided the foundation for decades of relative stability.

Hosted at Livadia Palace, a former summer residence of the Russian emperors on the Crimean peninsula, the meeting brought together Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin. Each leader had distinct objectives: Roosevelt aimed to secure America’s dominant position in the post-war world; Churchill sought to preserve Britain’s empire; and Stalin wanted to guarantee Soviet security and advance the interests of international socialism. Despite these stark differences, they sought common ground.

A key issue was the fate of the Far East. Stalin agreed to join the war against Japan once Germany was defeated but laid down firm conditions, demanding territory from Japan and recognition of Soviet interests in China. Though each leader conducted behind-the-scenes negotiations without informing the others, agreements regarding Asia were ultimately reached. In Europe, they decided Germany would be divided into occupation zones administered by the USSR and the Allies – the latter further split into American, British, and later French sectors.

The Allies planned Germany’s total demilitarization, denazification, and reparations payments, including forced labor. Poland fell within the Soviet sphere of influence; despite strong protests by Poland’s exiled government, the USSR gained territories in eastern Poland, compensating the Poles with German lands to the west, including parts of East Prussia, Pomerania, and Silesia. Although Stalin considered a coalition Polish government including diverse political factions, he already had a clear plan for Soviet control there. In contrast, Western and Southern Europe remained firmly in the Allied sphere.

The future structure of the United Nations was also extensively discussed at Yalta. Debates were intense and focused on maximizing each country’s influence. Stalin initially proposed separate UN representation for every Soviet republic, while Roosevelt envisioned a Security Council without veto powers. Ultimately, they agreed upon establishing the UN and a Security Council with veto power for major states, dedicated to preserving global peace and stability.

While Yalta did not achieve perfect justice, it set the stage for a world divided into spheres of influence – causing forced migrations, suffering, and political repression. Just as the Soviet Union brutally crushed Polish resistance, Britain harshly suppressed communist movements in Greece. Border changes forced millions from their homes: Germans were expelled from areas they had inhabited for centuries, Poles were displaced from Ukraine, and Ukrainians from Poland.

Nevertheless, at that moment in history, no better alternatives seemed viable. The Yalta agreements demonstrated that negotiation was possible, outlining a global structure that lasted nearly half a century. Today, the UN still functions, and its creation at Yalta reminds us that, despite deep differences, compromise and cooperation remain possible paths forward.

https://www.rt.com/russia/615248-from-yalta-to-today/?ysclid=m9jcbkk774600567958

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

commemoration....

Our common victory.

BY Olesya Orlenko

In the history of Europe, there are many events whose commemoration is shared by all the countries and peoples of the continent. One of these is the victory over Nazi Germany and fascism. This celebration of a shared tragedy, a united effort, and a common victory will take place in one way or another throughout Europe.

When it comes to these events, the names of heads of state, military commanders, and leaders of movements are most often mentioned. However illustrious they may have been, their efforts would have been in vain without the support of the people who heard and followed them. The peoples of the countries of Europe constitute the strength without which victory is impossible.

The knowledge that the struggle against Nazism was taking place throughout the continent gave all peoples the strength to resist and fight during this war. It was at the time of the union of these forces in the fight against Nazism and fascism that mutual understanding emerged between the peoples of countries with completely different state regimes. Let us recall that the documentary "The Defeat of the German Armies near Moscow" became the first Russian film to win an Oscar in the United States in 1943. Also, the welcome that Red Army fighter Lyudmila Pavlichenko, originally from the Kyiv region, "Lady Sniper," as Time Magazine called her in 1942, received from the American people during a visit to their country. Examples of this type are numerous.

Of course, years pass and times change. We cannot perceive past events with the same level of sensitivity. Needless to say, it is impossible to expect this from a generation born in the period after the events described. But the way we look at the founding moments of the past reflects not only the level of knowledge of the past, but also a society's vision of itself in the present. As Paul Ricoeu said, the role of dealing with the past should fall to historians on the one hand, and to the people on the other. And it is very dangerous when these subjects become objects of manipulation by politicians and the media that serve them. It is sad to note that in the current situation, events so dear to the memory of not only the Russian people, but also the French people, are being diverted to serve geopolitical interests. Unfortunately, the French media are also involved.

Having been interested in the Holocaust since childhood, I was particularly struck by the media coverage in France of issues related to the genocide of the Jews. On January 12 of this year, Le Monde published an article entitled "The Nazi extermination camp of Treblinka is gradually regaining its memory." This text focuses on the Nazi extermination camp of Treblinka, in Poland. After a summary of the camp's history, there is a narrative about preserving the memory of the prisoners who fell in combat. The author describes the work of the spouses Pawel and Ewa Sawicki to establish the number and identity of the Jews murdered in this camp and presents their motivation as follows: "He and his wife nourish the nostalgia for a Poland they never knew: that of a multicultural country that the Holocaust, the borders redrawn by the Yalta Agreements and four decades of communist rule made disappear."

It should be noted that this sentence equates genocide with state rule, which is not only wrong but scandalous. Furthermore, let us remember that before World War II, Poland was under the nationalist regime of Piłsudski. Of course, this was not a Nazi occupation regime. However, it would also be incorrect to paint an idyllic picture of Poland in the 1930s. [GUSNOTE: Although some aspects of Piłsudski's administration, such as imprisoning his political opponents at Bereza Kartuska, are controversial, he remains one of the most influential figures in Polish 20th-century history and is widely regarded as a founder of modern Poland.]

The newspaper could have responded that it was merely conveying the opinions of the protagonists of its article. But aren't the media supposed to present their story in a balanced manner? In this article, there is not the slightest mention of Vasily Grossman, who first spoke about this extermination camp in a note entitled "The Hell of Treblinka," which was included among the prosecution's documents at the Nuremberg Trials. The other article about Treblinka, published in Le Monde a little later, mentions his name once, stating that he was a "Soviet journalist" who "arrived on the scene in September 1944." First of all, there's an error. Soviet troops liberated the territory where Treblinka was located in July 1944, and Vassily Grossman accompanied the troops. Furthermore, the article makes no mention of the Red Army or the fact that it liberated this territory. We therefore don't know the circumstances under which the Soviet correspondent ended up there.

Will it be said that this was just a coincidence and that Le Monde journalists are being overly criticized? Alas, no. This tendency is explicitly reflected in another article in the newspaper about the Auschwitz death camp. The text represents an interview with historian Tal Bruttmann, a leading specialist in this historical subject. He presents his analysis of how the images left by Auschwitz's grim period of operation have influenced the study of its history, as well as that of the Holocaust.

However, here is what he says about the liberation of this death camp: "... 'liberation' suggests that the camps were tactical or strategic objectives for the Allied armies, when this was never the case... Auschwitz is emblematic in this regard. The Red Army had captured Krakow a few days earlier, and the road leading west passed through Auschwitz... When, on January 27, 1945, it successively reached Monowitz (Auschwitz III), Auschwitz I, and Birkenau (Auschwitz II), a few SS men were still there, which provoked skirmishes. Prisoners were also there, but most had been evacuated..." Then he adds: "The Soviets... 'discovered' Auschwitz in the literal sense: they stumbled upon it... they 'opened' it, and took care of the survivors... But talking about the 'liberation' of the camp, in the strict sense, is meaningless."

Errors again in the pages of Le Monde. Thanks to declassified documents, we have proof that the world knew about the existence of the Nazi death camps and the extermination of certain categories of prisoners, the overwhelming majority of whom were Jews. But, of course, no one suspected the true scale of what was happening, for example, at Auschwitz. What the world saw and learned after the Allied liberation of the death camps had to be analyzed and structured over a long period. Of course, the Red Army didn't know what Auschwitz represented. At least not as we know it today.

During their advance into Poland, the Soviets received information about the existence of a Nazi concentration camp. The commander of the Soviet 60th Army, P.A. Kurochkin, decided to change the direction of the attack and direct it towards the town of Auschwitz, near the death camp. During the attack on the camp, there were doctors among the Soviet troops, a rare practice for the Red Army and one that was not repeated subsequently. This means that the Soviets understood that there were people in front of them who needed immediate medical assistance. Therefore, in this case, Auschwitz became a strategic target. During the fighting to liberate the camp, approximately 300 Soviet soldiers and officers were killed, including the commander of the 472nd Rifle Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Semyon Besprozvanny, former director of the Bolshoi Drama Theater and the Central Park of Culture and Recreation in Leningrad. So, there were real battles, not "skirmishes."

Another important point: the SS remained at Auschwitz to kill the prisoners who could not leave the camp on foot. Tal Bruttmann even says in his interview that there were 7,000 of them. Otto Frank, Anne Frank's father, Eva Mozes Kor, a victim of Josef Mengele's medical experiments, and also French nationals were among those prisoners rescued thanks to the Red Army.

Of course, our current attitude toward the past should not be seen as a political stance of today. Otherwise, our consciousness will be subject to modern attitudes that tell us what we should think and what we shouldn't talk about. We all know how deeply human consciousness is influenced by society and every imaginable context. But shouldn't the media be the instrument that allows us to resist the processes that can subjugate us and force us to be puppets in someone else's game?

I would like to end this long text by congratulating the peoples of all countries who waged a heroic struggle that allowed humanity to avoid a monstrous catastrophe, as we approach the day of our common Victory!

Olesya Orlenko

Russian historian.

https://www.legrandsoir.info/notre-victoire-commune.html

TRANSLATION BY JULES LETAMBOUR. ANNOTATION AND TYPE-STYLE INCLUSION BY GUS.

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

reinvention....

Evelyn Goh

Navigating a world of revisionist powersWe are living in a world with three leading great powers — all with explicitly revisionist aims when it comes to the international “rules-based order”.

For those accustomed to thinking about global order as being centred on great powers, this is the most significant reinvention of that order since the end of the Cold War.

Since its formation, Russia has invaded its neighbours and taken territory and populations by force [GUS: THIS WAS ONLY DONE UNDER UN CHARTER TO PROTECT THE RUSSIAN POPULATIONS OF UKRAINE AND ALSO TO PREVENT NATO COMING TO RUSSIA'S DOORSTEP]. Since 1950, the United States and its allies have worried about China’s stated imperative to reunify Taiwan and assertions of its maritime territorial claims. In 2025, the United States, under the second Donald Trump presidency, has announced an agenda to “take” Greenland and annex Canada. Revisionist powers do not play by agreed rules.

In radically revising the terms of trade, Trump follows a long line of US leaders since 1945 struggling with the Triffin dilemma – the provider of the international reserve currency cannot sustain currency convertibility alongside control over domestic currency valuation and trade balances. Previous US leaders wielded monetary instruments to control inflation and improve current account deficits. Trump is now using the blunter instruments of raising tariffs and cutting foreign aid, with the ostensible aim of improving US export access and competitiveness.

Trump’s tariffs ring the death knell of the low- or no-tariff global trading system. Trump’s giant shove is likely to stimulate economic initiatives among “the rest” excluding the United States. The ultimate decoupling may turn out to be between the United States and the rest of the world, not just the United States and China.

A revisionist regime in Washington also presents opportunity to think equally unpalatable thoughts about a new US–China economic-security bargain.

Transglobal technologies will continue to break borders, but geography may reassert itself too. A more self-centred United States is much less likely to conduct military campaigns on the other side of the world, while Europe will be forced to deal directly with the Russia threat. East Asia must learn to live with a risen China without an unreliable offshore balancer.

The rest of the world is a large and amorphous bunch. They can, and have been, followers, pawns or sites of great power rivalry and conflict. But they can and have also been innovators, leaders, collective action specialists and out-of-the-box thinkers and shakers. Consider the Non-Aligned Movement, the European and African Unions, the BRICS’ New Development Bank and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, to name a few examples.

Regions including East, South and Central Asia, Africa, Latin America and parts of the Middle East are used to value-diverse, dynamic and often dangerous environments. They have had to navigate regional and international orders not of their own making, and make their way without neat categories of perpetual friends or sworn enemies. They may hate it, and dread the costs, but the Global Majority is better prepared psychologically to face the current world of relative revisionism.

At this juncture, being willing to go beyond old assumptions and to ask different questions will help all countries to navigate the new normal of an international system dominated by three revisionist great powers.

One supposedly worst-case scenario under discussion in Canberra is that Southeast Asia falls into China’s sphere of influence. Australia has limited direct ability to prevent that development, yet it’s a scenario that’s unlikely to eventuate. Fear about the potential “loss” of Southeast Asia is misplaced.

Regional doubts about the United States are not new. The United States has allies and firm friends, but Southeast Asia does not see it the same way as Australia – it’s regarded the United States as neither a necessarily benign nor an altruistic hegemon.

Southeast Asian responses to Chinese power are also not conditioned mainly by what they think about the United States. Southeast Asians largely do not see themselves as living in a world circumscribed by two great powers locked in rivalry. Most engage in hedging, omni-enmeshment and complex balancing, and their conception is of a layered hierarchical regional order.

Because of China’s vital role in economic production and as a growing source of investment and consumption, the region’s main concern now is the consequence of a serious and prolonged economic slowdown in China. This will impose a huge, additional strain upon Southeast Asia’s economic prospects on top of US-created volatility. The Trump tariffs will compel some regional economies to manage an even greater influx of cheaper Chinese products. Yet the major regional worry is not centred on China’s economic strength, which is viewed as good for a region that has experience in managing the asymmetry of power with its neighbouring giant.

A potential Chinese sphere of influence recedes as a central worry in a world filled with revisionist great powers. Precisely because the United States may remain aloof, the region will have to continue to work closely with what they hope will be an economically vibrant China. And because China is part of many of the region’s territorial and other conflicts, Southeast Asia must continue to manage regional conflicts as best it can.

This is not necessarily a recipe for simply giving in to Chinese demands. As a whole, Southeast Asia has not been keen on balancing with the United States, even when that option seemed available. The current situation only exacerbates Southeast Asian imperatives to find their own ways of living with multiple revisionist powers.

Especially for allies deeply integrated with the United States, a defining era is over, and they must fundamentally reimagine their economic and political security. This rethinking and retooling is politically fraught, involves very costly trade-offs in domestic spending and could take decades.

Republished from East Asia Forum, 1 June 2025

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/06/navigating-a-world-of-revisionist-powers/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.