Search

Recent comments

- arrest that man.....

8 hours 59 min ago - monstrous...

11 hours 28 min ago - chomsky's advice....

13 hours 58 min ago - destroying america....

16 hours 58 min ago - critic....

18 hours 1 min ago - talking....

18 hours 43 min ago - one nation's fairies....

20 hours 12 min ago - assassination....

20 hours 22 min ago - "error"...

21 hours 41 min ago - playground....

21 hours 42 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a criminal culture ....

Barclays PLC and its subsidiaries have agreed to pay more than $450 million to settle charges that it attempted to manipulate and made false reports related to setting key global interest rates.

The rates indirectly affect the costs of hundreds of trillions of dollars in loans that people pay when they get loans to go to school, purchase a car or buy a house.

Britain's Barclays was just one of numerous major banks reportedly under investigation for similar violations.

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission said Wednesday that the incidents occurred between 2005 and 2009 and sometimes took place daily. The $200 million civil penalty levied against Barclays as part of the settlement is the largest in the agency's history.

Barclays is also paying $160 million to the U.S. Justice Department and almost $93 million to British regulators.

The CFTC said Barclays senior management and multiple traders were involved in the matter and that they also coordinated with traders at other banks to make false submissions. The data was used in determining the London interbank offered rate - known as LIBOR_ and Euribor rates, which influence many other interest rates.

"Banks must not attempt to influence LIBOR or other indices based upon concerns about their reputation or the profitability of their trading positions," CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler said in a statement.

The LIBOR is an average rate set by banks each morning that measures how much they're going to charge each other for loans. That in turn affects the costs consumers pay for loans and investments.

Barclays also agreed to pay $160 million as part of an agreement with the fraud section of the Justice Department's criminal division on a related matter. The Justice Department said its related criminal investigation continues, and Barclays agreed to cooperate with that probe as part of its settlement.

Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer said that Barclays was the first bank to cooperate extensively with the investigation. Barclay's cooperation greatly helped the Justice Department in the probe, he said.

Britain's Financial Services Authority levied a fine of 59.5 million pounds ($92.7 million), the biggest fine ever imposed by the British regulator.

"Barclays' misconduct was serious, widespread and extended over a number of years," Tracey McDermott, acting director of enforcement and financial crime at the British agency, said in a statement. "The integrity of benchmark reference rates ... is of fundamental importance to both U.K. and international financial markets. Firms making submissions must not use those submissions as tools to promote their own interests."

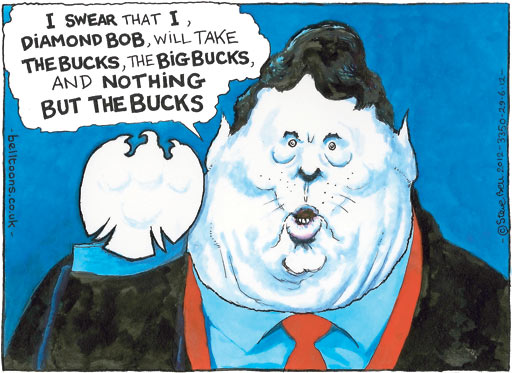

Barclays President Bob Diamond also announced he and three senior bank executives were waiving any bonus for the year as a result of the case.

The other executives include Group Finance Director Chris Lucas, Chief Operating Officer Jerry del Missier and Chief Executive of Corporate and Investment Banking Rich Ricci.

Barclays Libor Charges: Bank To Pay $450 Million To Settle Charges Of Market Manipulation

- By John Richardson at 29 Jun 2012 - 9:34am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

from the cess-pit .....

The Government was under growing pressure last night to call a public inquiry into the behaviour of Britain's bankers as the Business Secretary, Vince Cable, admitted the sector was a “massive cesspit” that needed cleaning up.

Even business leaders turned on the City and demanded a cull at the top of British banks, with some investors at Barclays agitating for a management change after its £290m fine for trying to fix Libor, the rate banks charge to borrow from each other.

The Bank of England Governor, Sir Mervyn King, launched a scathing attack on the banking industry and demanded a "real change in culture".

Bob Diamond, the chief executive of Barclays, could be called before Parliament as early as Wednesday to answer questions about when he first became aware of the practice. The bank's chairman, Marcus Agius, will probably also be called to appear "if he is still in a job," sources on the Treasury Select Committee said.

Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, called for a judge-led inquiry into the industry, asserting that the problem "goes far beyond individuals". But he also singled out Mr Diamond, adding to the pressure on him to resign: "I think it's pretty clear that change is required at Barclays. It's very hard to see that being led by Bob Diamond."

The head of the Institute of Directors, Simon Walker, said it was "high time" for a "clear-out" of top bankers after a wave of scandals including mis-selling and market manipulation.

It was also reported last night that Barclays failed to act on three internal warnings, between 2007 and 2008, relating to the way it set Libor rates.

Cable: The City Is A Massive Cesspit

ho hum .....

from Crikey …..

Rundle: what chance a UK bank to trust? Barclays and none

Guy Rundle writes from London:

BARCLAYS BANK, BOB DIAMOND, MARCUS AGIUS, MORGAN STANLEY, UK ECONOMY, US BANKS, US ECONOMY

In London, 'tis the bonfire of the bankers. The chairman of Barclays bank, Marcus Agius, has agreed to resign after relentless pressure following the revelation of a massive scheme of interest-rate fixing.

The move is widely seen as a last-ditch measure to protect Barclays' CEO, brash US-born Bob Diamond, who has made it clear that he will not be going without a struggle.

Diamond has been summoned to appear before a Commons subcommittee on Wednesday, and there is no question that he will get a rough time from all parties.

Diamond has resolutely refused to resign. Indeed, on Thursday afternoon he stormed into the office of Morgan Stanley, to assert that he wouldn't be going anywhere - after the agency had recommended selling Barclays stock following the scandal.

In 72 hours last week, Barclays lost 15% of its value, after revelation of its Libor scandal first became known. Libor is the London Interbank Offered Rate - which sets the base rate for thousands of financial products.

Investigation of Barclays showed that its traders, and traders from other firms working with it, had simply disregarded any and all "Chinese walls" within and between financial groups as regards the Libor.

Barclays, one of the biggest banks in the UK, was the one most exposed by a high Libor, so it made every effort to keep it low, thus making its balance sheet look healthier (it's more complicated than that; there's a useful summary at The Guardian here)

Barclays has subsequently been fined nearly 300 million for its part in the process - which went on between 2005 and 2009 - and the most heat has fallen on Diamond, who was not then CEO of Barclays, but was head of the division responsible for Libor manipulation.

Revelations of the Libor-fixing scandal have created a new wave of moral revulsion towards bankers in the UK, with head of the bank of England Mervyn King coming out and saying that the banking culture had become toxic, and there was no way of knowing, etc - however there have been suggestions that the Bank of England was aware of the practice all along.

Furthermore, it is difficult to identify a huge class of victims of the scandal, since it did not involve a manipulation of the sterling Libor rate - which covers nearly half a million mortgages and loans - but was related to the dollar Libor rate, and the Euribor rate. But UK-owned businesses working in euros, and those paying off overseas holiday homes through UK banks would have been disadvantaged. They are not, however, the epitome of "suffering humanity".

However, it seems likely that the scandal has only been partially revealed, and that at least nine other banks are involved in a broader version of the scandal. The US Securities and Exchange Condition has now started to work with the UK FSA (Financial Services Authority) on a much broader investigation - and that may well open up in an unknowable fashion, encompassing the whole US-UK banking system.

Nevertheless, the scandal itself is another example of the weird politics of the contemporary period. The wholesale processes by which banks and others wrecked the economy in 2007-08 has escaped substantial outrage.

It is this scandal that appears to have stirred up people to a new level of outrage against bankers - even though direct victims have been few and far between. Again, there is a split in the UK between the elite process of politics - in which everyone makes a performance of outrage, even though both parties encouraged bankers to acts as free agents throughout the first decades of the 2000s.

The mass of the population, for whom banks are a series of massive faceless conglomerates with little to choose between them, remains, as far as one call tell, largely unmoved by these events. The scandal itself is nearly incomprehensible to someone who does not focus on it with some attention, or have some knowledge of the world of finance.

In a class-ridden society such as the UK, many people will simply regard it as the doings of those who run their lives through networks of privilege.

For the UK bankers, the main risk remains the interest by US authorities in the scandal. The UK has all but thrown up its hands to say that the scandal is unprosecutable; the US tends to have a lot more scope to prosecute.

This is hardly an unambiguous good. As with the notorious "Natwest Three" case, the US may be able to prosecute - and to extradite under fast-track arrangements - dozens of banking executives for activities done entirely in the UK. No one would shed a tear, and thus the paradoxical effect of this scandal would be to legitimate a system that can spirit people across borders willy-nilly.

Agius' head will not be the last to roll, but I suspect that much of this will go on with barely any attention. It remains to be seen what sort of scandal would stir people to the next level - to actually want to control capital as a social resource, and set some conditions and limits.

'Tis the bonfire of the bankers. And children off somewhere who do not particularly want it to happen.

then .....

Marcus Agius, the chairman of Barclays, resigned on Monday, saying “the buck stops with me.” His was the first departure since the British bank agreed last week to pay $450 million to settle findings that, from 2005 to 2009, it had tried to rig benchmark interest rates to benefit its own bottom line.

Mr. Agius was right to go and the bank’s chief executive, Robert Diamond Jr., should follow him out the door. But the investigations cannot stop there.

The rates in question - the London interbank offered rate, or Libor, and the Euro interbank offered rate, or Euribor - are used to determine the borrowing rates for consumers and companies, including some $10 trillion in mortgages, student loans and credit cards. The rates are also linked to an estimated $700 trillion market in derivatives, which banks buy and sell on a daily basis. If these rates are rigged, markets are rigged - against bank customers, like everyday borrowers, and against parties on the other side of a bank’s derivatives deals, like pension funds.

Barclays is only one of more than a dozen big banks that provide information used to set the daily rate for Libor and Euribor. The settlement, struck with regulators in Washington and London and with the Department of Justice, indicates that the bank did not act alone. It shows that unnamed managers and traders of Barclays in London, New York and Tokyo colluded with or prevailed upon bank employees who provide the benchmark data to make false reports. The aim was to bolster Barclays’s trading positions and to aid or counteract other banks’ attempts at manipulation.

The evidence, cited by the Justice Department - which Barclays agreed is “true and accurate” - is damning. “Always happy to help,” one employee wrote in an e-mail after being asked to submit false information. “If you know how to keep a secret, I’ll bring you in on it,” wrote a Barclays trader to a trader at another bank, referring to an attempt to align their strategies for mutual gain.

If that’s not conspiracy and price-fixing, what is?

The Justice Department has left open the possibility of prosecuting officers or employees of Barclays. But it has agreed not to prosecute the bank itself, in part because Barclays was the first to cooperate in the investigation and has agreed to keep cooperating. Such an agreement makes sense only if that cooperation will allow prosecutors to nail other banks that have been involved in setting the rates, including potential cases against Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and HSBC, and people who work there.

To date, the Justice Department has not distinguished itself in prosecuting major banks or their executives for conduct leading up to and during the financial crisis. But with Barclays now cooperating, the “Libor scandal” is another chance for government prosecutors to unmask and punish financial wrongdoing.

Rigged Rates, Rigged Markets

and now …..

Robert E. Diamond Jr., the chief executive of Barclays, resigned on Tuesday less than a week after the British bank agreed to pay $450 million to settle accusations that it had tried to manipulate key interest rates to benefit its own bottom line.

Mr Diamond’s resignation, which was effective immediately, follows mounting criticism of Barclays’ actions from politicians and shareholders.

Prime Minister David Cameron had called on individuals to take responsibility, while other British politicians had said Mr. Diamond should resign.

· ‘‘My motivation has always been to do what I believed to be in the best interests of Barclays,’’ Mr. Diamond said in a statement. ‘‘No decision over that period was as hard as the one that I make now to stand down as chief executive. The external pressure placed on Barclays has reached a level that risks damaging the franchise. I cannot let that happen.’’

Marcus Agius, the bank’s chairman, who resigned on Monday, will now stay at the bank and lead the search for a new chief executive, according to a statement from Barclays.

Mr. Agius will head the executive committee at Barclays until a new chief executive is appointed, and will be supported by Michael Rake, the bank’s deputy chairman.

While Mr. Diamond is stepping down at Barclays, he will face continued scrutiny Wednesday when he testifies before a British parliamentary committee.

Local politicians are expected to question him about the actions within the bank that led to the multimillion-dollar fines from the Justice Department and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the United States and the Financial Services Authority in Britain.

Fresh details about the case show how Mr. Diamond and other senior executives played a role in the questionable actions and failed to prevent them, according to several people familiar with the details of the case.

In 2007 and 2008, Mr. Diamond’s top deputies told employees to report artificially low rates in line with its rivals, deflecting scrutiny about the health of Barclays at the height of the financial crisis, according to the people, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Barclays declined to comment about the involvement of senior executives.

Mr Diamond’s resignation follows a settlement that Barclays struck last week with the American and British authorities, part of wide-ranging inquiry into how big banks set certain benchmarks, including the London interbank offered rate, or Libor.

Those rates are used to determine the costs of $350 trillion in financial products, including credit cards, mortgages and home loans. American and international regulators are investigating several other banks, including HSBC, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup.

In a letter to Barclays employees on Monday, Mr. Diamond said he was ‘‘disappointed and angry’’ about the bank’s past attempts to manipulate key interest rates.

‘‘I am disappointed because many of these behaviors happened on my watch,’’ he wrote.

The changes in Barclays’ leadership come after Mr. Diamond helped transform Barclays’ investment bank into a major player on Wall Street.

The American-born Mr. Diamond joined the British bank in the late 1990’s and quickly expanded the investment banking unit into new areas, such as commodities and derivatives trading.

At the height of the financial crisis, Mr. Diamond, then the head of the investment bank, Barclays Capital, extended the firm’s presence in the United States by acquiring the North American operations of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

‘‘I am deeply disappointed that the impression created by the events announced last week about what Barclays and its people stand for could not be further from the truth,’’ Mr. Diamond said in a statement on Tuesday.

Robert Diamond, Chief Executive of Barclays, Resigns

beware a worm on the turn .....

Bob Diamond, the boss of Barclays who has resigned from the embattled bank, was expected to come out fighting for his reputation on Wednesday when he appears before a powerful committee of MPs.

The high-profile and outspoken banker is expected to unleash a wave of explosive revelations about the role of City watchdogs and senior Whitehall figures in the manipulation of crucial interest rates that landed the bank with a record £290m fine last week.

The chancellor, George Osborne, who had been putting the banker under intense pressure to quit, said his sudden resignation was "the right decision for Barclays – and for the country". "I think Bob Diamond's resignation is the first step towards the new age of responsibility we need to see."

After an extraordinary 24 hours during which the bank's chairman, Marcus Agius, quit only to be temporarily reinstated once Diamond had departed, the role of Bank of England officials in the rate-rigging scandal is likely to take centre stage in the hearing with MPs.

With Barclays in turmoil, Diamond is fighting for his own reputation, which politicians have used to symbolise the culture of greed in City banking. Diamond, under pressure from the banking regulator and the governor of the Bank of England, Sir Mervyn King, quit after he decided he would be the lightning rod for the scandal at the hearing.

The American-born banker, who could be in line for a payoff of £22m, is facing pressure to walk away with nothing after being paid £100m by the bank in the past six years. There are also calls by shareholders for the bank to look at ways of clawing back bonuses paid in the past.

In a statement, Diamond said: "I am deeply disappointed that the impression created by the events announced last week about what Barclays and its people stand for could not be further from the truth."

At his appearance before the Treasury select committee of MPs – chaired by the Conservative MP Andrew Tyrie, who the government has also appointed to lead a parliamentary inquiry into banking – Diamond will try to explain the bank's actions for the period between 2005 and 2009, when the attempts to manipulate Libor took place.

Barclays released an email written by Diamond recording a conversation with Paul Tucker, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, in October 2008, which will be scrutinised by the MPs.

The sequence of events unleashed by the email in the darkest days of the banking crisis also forced the departure of Jerry del Missier, who was Diamond's closest colleague at the bank.

Del Missier, a Canadian, was promoted to chief operating officer a fortnight ago, but was named as the top executive who instructed more junior staff to lower the bank's submissions to the key benchmark rate, the London interbank offered rate (Libor), at the centre of the current scandal.

MPs will be keen not to let the controversy over the potential involvement of the Bank of England – and unnamed Whitehall officials – to detract from regulatory evidence that prior to the 2008 crisis, Barclays traders were attempting to manipulate Libor to help boost the bank's profits. Emails that read, "This one's for you, big boy" and references to bottles of Bollinger champagne are hard for the bank to explain.

Diamond will admit that in the period from 2005 to 2007, when traders were trying to profit from Libor movements, the bank – along with others – believed it was a low-risk business and that it did not have systems in place to prevent the manipulation taking place.

A submission by the bank to the Treasury select committee of MPs ahead of Diamond's appearance shows that the former chief executive will say there was no knowledge by anyone in the bank above desk supervisor level of this conduct at the time.

"Senior management were not aware," the Barclays submission says.

In the submission, the bank was quick to apologise. "These explanations are in no way intended to excuse any of the events that occurred. These events should never have taken place, and Barclays deeply regrets that they did," the document said. The Libor rigging occurred over two phases: the first from 2005, when traders were changing rates at the request of rivals and colleagues, and the second during the banking crisis, when a conversation between Tucker and Diamond is becoming a key focus.

Diamond has made clear that he did not believe that Tucker had ordered him to lower the bank's submission to Libor – to help avoid any false impression that the bank was in difficulty – but Del Missier interpreted Diamond's remarks in a different way.

But the reference in the email to Whitehall sources asking Tucker why Barclays' submissions were higher than those of its rivals sparked speculation about potential involvement from government ministers.

Alistair Darling, the former Labour chancellor, said it was important that the Treasury select committee call Tucker "at the earliest possible opportunity" to ask for his account of the conversation with Diamond. He added that he had made no calls to the bank asking them to put pressure on anyone to lower Libor rates.

Asked if the Bank of England had ordered the banks to lower its rates, he said: "I would find it absolutely astonishing that the Bank would ever make such a suggestion, and equally I can think of no circumstances that anyone in departments for which I was responsible – the Treasury – would ever suggest wrongdoing like this."

He added: "At the time these calls were made in 2008 it was just after Lehmans had collapsed, and just after the bank rescues, one of the things you looked at was how much it was costing banks to borrow because that gave you an assessment of their financial standing that is why it was so critically important."

He said the way to get the Libor rate down at the time was through policy such as credit guarantee scheme, and the special liquidity scheme.

A spokesman for another minister at the time, Lady Vadera, said: "She has no recollection of speaking to Paul Tucker or anyone else at the Bank of England about the price-setting of Libor."

Diamond is expected to tell MPs that when he was running the investment banking arm, Barclays Capital, the bank told the British Bankers' Authority, which ran the rate-setting process, that it was "consistently concerned" during the crisis about the lower rates being submitted by rivals. In the Lords, Lord Myners, Labour's City minister during the banking crisis, contended that the BBA executive had been warned of Libor rate-rigging, but chose to do nothing about it.

Myners said: "What we need to do is to understand what went wrong here, which has cost this country so much – 7% of national output in perpetuity, millions of people placed in a position of distress, unemployment, worry about their mortgages – they're not going to be satisfied by an inquiry led by politicians."

The anger unleashed by the fine on Barclays – which is expected to be followed by regulatory actions – has led the government to attempt to set up a committee of Lords and MPs into banking. MPs will be asked to vote on Thursday whether to set up a parliamentary inquiry of peers and MPs into the banking crisis, as proposed by the government, or instead set up a judge-led inquiry, as proposed by Labour.

In the absence of any further private talks in advance of the vote, Labour will lose and will then have to decide whether to co-operate with the parliamentary inquiry or in effect block any inquiry by refusing to sit on the committee.

Ministers are already preparing to accuse Labour of running to hide from its responsibilities for the banking crisis if it blocks an inquiry, and continues to insist only a Judge led inquiry will be effective.

Bob Diamond Quits Barclays - Libor Scandal

a tobacco moment ....

The most memorable incidents in earth-changing events are sometimes the most banal. In the rapidly spreading scandal of LIBOR (the London inter-bank offered rate) it is the very everydayness with which bank traders set about manipulating the most important figure in finance. They joked, or offered small favours. “Coffees will be coming your way,” promised one trader in exchange for a fiddled number. “Dude. I owe you big time!… I’m opening a bottle of Bollinger,” wrote another. One trader posted diary notes to himself so that he wouldn’t forget to fiddle the numbers the next week. “Ask for High 6M Fix,” he entered in his calendar, as he might have put “Buy milk”.

What may still seem to many to be a parochial affair involving Barclays, a 300-year-old British bank, rigging an obscure number, is beginning to assume global significance. The number that the traders were toying with determines the prices that people and corporations around the world pay for loans or receive for their savings. It is used as a benchmark to set payments on about $800 trillion-worth of financial instruments, ranging from complex interest-rate derivatives to simple mortgages. The number determines the global flow of billions of dollars each year. Yet it turns out to have been flawed.

Over the past week damning evidence has emerged, in documents detailing a settlement between Barclays and regulators in America and Britain, that employees at the bank and at several other unnamed banks tried to rig the number time and again over a period of at least five years. And worse is likely to emerge. Investigations by regulators in several countries, including Canada, America, Japan, the EU, Switzerland and Britain, are looking into allegations that LIBOR and similar rates were rigged by large numbers of banks. Corporations and lawyers, too, are examining whether they can sue Barclays or other banks for harm they have suffered. That could cost the banking industry tens of billions of dollars. “This is the banking industry’s tobacco moment,” says the chief executive of a multinational bank, referring to the lawsuits and settlements that cost America’s tobacco industry more than $200 billion in 1998. “It’s that big,” he says.

As many as 20 big banks have been named in various investigations or lawsuits alleging that LIBOR was rigged. The scandal also corrodes further what little remains of public trust in banks and those who run them.

Like many of the City’s ways, LIBOR is something of an anachronism, a throwback to a time when many bankers within the Square Mile knew one another and when trust was more important than contract. For LIBOR, a borrowing rate is set daily by a panel of banks for ten currencies and for 15 maturities. The most important of these, three-month dollar LIBOR, is supposed to indicate what a bank would pay to borrow dollars for three months from other banks at 11am on the day it is set. The dollar rate is fixed each day by taking estimates from a panel, currently comprising 18 banks, of what they think they would have to pay to borrow if they needed money. The top four and bottom four estimates are then discarded, and LIBOR is the average of those left. The submissions of all the participants are published, along with each day’s LIBOR fix.

In theory, LIBOR is supposed to be a pretty honest number because it is assumed, for a start, that banks play by the rules and give truthful estimates. The market is also sufficiently small that most banks are presumed to know what the others are doing. In reality, the system is rotten. First, it is based on banks’ estimates, rather than the actual prices at which banks have lent to or borrowed from one another. “There is no reporting of transactions, no one really knows what’s going on in the market,” says a former senior trader closely involved in setting LIBOR at a large bank. “You have this vast overhang of financial instruments that hang their own fixes off a rate that doesn’t actually exist.”

A second problem is that those involved in setting the rates have often had every incentive to lie, since their banks stood to profit or lose money depending on the level at which LIBOR was set each day. Worse still, transparency in the mechanism of setting rates may well have exacerbated the tendency to lie, rather than suppressed it. Banks that were weak would not have wanted to signal that fact widely in markets by submitting honest estimates of the high price they would have to pay to borrow, if they could borrow at all.

In the case of Barclays, two very different sorts of rate fiddling have emerged. The first sort, and the one that has raised the most ire, involved groups of derivatives traders at Barclays and several other unnamed banks trying to influence the final LIBOR fixing to increase profits (or reduce losses) on their derivative exposures. The sums involved might have been huge. Barclays was a leading trader of these sorts of derivatives, and even relatively small moves in the final value of LIBOR could have resulted in daily profits or losses worth millions of dollars. In 2007, for instance, the loss (or gain) that Barclays stood to make from normal moves in interest rates over any given day was £20m ($40m at the time). In settlements with the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in Britain and America’s Department of Justice, Barclays accepted that its traders had manipulated rates on hundreds of occasions. Risibly, Bob Diamond, its chief executive, who resigned on July 3rd as a result of the scandal (see article), retorted in a memo to staff that “on the majority of days, no requests were made at all” to manipulate the rate. This was rather like an adulterer saying that he was faithful on most days.

Barclays has tried its best to present these incidents as the actions of a few rogue traders. Yet the brazenness with which employees on various Barclays trading floors colluded, both with one another and with traders from other banks, suggests that this sort of behaviour was, if not widespread, at least widely tolerated. Traders happily put in writing requests that were either illegal or, at the very least, morally questionable. In one instance a trader would regularly shout out to colleagues that he was trying to manipulate the rate to a particular level, to check whether they had any conflicting requests.

The FSA has identified price-rigging dating back to 2005, yet some current and former traders say that problems go back much further than that. “Fifteen years ago the word was that LIBOR was being rigged,” says one industry veteran closely involved in the LIBOR process. “It was one of those well kept secrets, but the regulator was asleep, the Bank of England didn’t care and…[the banks participating were] happy with the reference prices.” Says another: “Going back to the late 1980s, when I was a trader, you saw some pretty odd fixings…With traders, if you don’t actually nail it down, they’ll steal it.”

Galling as the revelations are of traders trying to manipulate rates for personal gain, the actual harm done would probably have paled in comparison with the subsequent misconduct of the banks. Traders acting at one bank, or even with the clubby co-operation of counterparts at rival banks, would have been able to move the final LIBOR rate by only one or two hundredths of a percentage point (or one to two basis points). For the decade or so before the financial crisis in 2007, LIBOR traded in a relatively tight band with alternative market measures of funding costs. Moreover, this was a period in which banks and the global economy were awash with money, and borrowing costs for banks and companies were low.

“Clean in principle”

Yet a second sort of LIBOR-rigging has also emerged in the Barclays settlement. Barclays and, apparently, many other banks submitted dishonestly low estimates of bank borrowing costs over at least two years, including during the depths of the financial crisis. In terms of the scale of manipulation, this appears to have been far more egregious—at least in terms of the numbers. Almost all the banks in the LIBOR panels were submitting rates that may have been 30-40 basis points too low on average. That could create the biggest liabilities for the banks involved (although there is also a twist in this part of the story involving the regulators).

As the financial crisis began in the middle of 2007, credit markets for banks started to freeze up. Banks began to suffer losses on their holdings of toxic securities relating to American subprime mortgages. With unexploded bombs littering the banking system, banks were reluctant to lend to one another, leading to shortages of funding system-wide. This only intensified in late 2007 when Northern Rock, a British mortgage lender, experienced a bank run that started in the money markets. It soon had to be taken over by the state. In these febrile market conditions, with almost no interbank lending taking place, there were little real data to use as a basis when submitting LIBOR. Barclays maintains that it tried to post honest assessments in its LIBOR submissions, but found that it was constantly above the submissions of rival banks, including some that were unmistakably weaker.

At the time, questions were asked about the financial health of Barclays because its LIBOR submissions were higher. Back then, Barclays insiders said they were posting numbers that were honest while others were fiddling theirs, citing examples of banks that were trying to get funding in money markets at rates that were 30 basis points higher than those they were submitting for LIBOR.

This version of events has turned out to be only partly true. In its settlement with regulators, Barclays owned up to massaging down its own LIBOR submissions so that they were more or less in line with those of their rivals. It instructed its money-markets team to submit numbers that were high enough to be in the top four, and thus discarded from the calculation, but not so high as to draw attention to the bank (see chart 1). “I would sort of express us maybe as not clean, but clean in principle,” one Barclays manager apparently said in a call to the FSA at the time.

Confounding the issue is the question of whether Barclays had, or thought it had, the tacit support of both its regulator and the Bank of England (BoE). In notes taken by Mr Diamond, then the head of the investment-banking division of Barclays, of a call with Paul Tucker, then a senior official at the BoE, Mr Diamond recorded what was interpreted by some in the bank as a nudge and a wink from the central bank to fudge the numbers (see article). The next day the Barclays submissions to LIBOR were lower. This could be a crucial part of the bank’s defence.

The allegation by Barclays that some banks seemed to be fiddling their data would appear to be supported by the data themselves. Over the period of the financial crisis, the estimates of its borrowing costs submitted by Barclays were generally among the top four in the LIBOR panel (see chart 2). Those consistently among the lowest four were some of the soundest banks in the world, with rock solid balance-sheets, such as JPMorgan Chase and HSBC. However, among banks regularly submitting much lower borrowing costs than Barclays were banks that subsequently lost the confidence of markets and had to be bailed out. In Britain these included Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and HBOS.

The tobacco moment

Regulators around the world have woken up, however belatedly, to the possibility that these vital markets may have been rigged by a large number of banks. The list of institutions that have said they are either co-operating with investigations or being questioned includes many of the world’s biggest banks. Among those that have disclosed their involvement are Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, JPMorgan Chase, RBS and UBS.

Court documents filed by Canada’s Competition Bureau have also aired allegations by traders at one unnamed bank, which has applied for immunity, that it had tried to influence some LIBOR rates in co-operation with some employees of Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, ICAP, JPMorgan Chase and RBS. It is not clear whether employees of these banks actually co-operated or, if they did, whether they succeeded in manipulating rates.

Continental Europe is focusing on cartel effects rather than digging into the internal culture of banks. Separate investigations, by the European Commission and the Swiss authorities, focus on the possible effects of inter-bank rate manipulation on end users. Last October European Commission officials raided the offices of banks and other companies involved in trading derivatives based on EURIBOR (the euro inter-bank offered rate). The Swiss competition commission launched an investigation in February, prompted by an “application for leniency” by UBS, into possible adverse effects on Swiss clients and companies of alleged manipulation of LIBOR and TIBOR (the Tokyo inter-bank offered rate) by the two Swiss and ten other international banks and “other financial intermediaries”.

The regulatory machinery will grind slowly. Investigators are unlikely to produce new evidence against other banks for a few months yet. Slower still will be the progress of civil claims. Actions representing a huge variety of plaintiffs have been launched. Among the claimants are investors in savings rates or bonds linked to LIBOR, those buying derivatives priced off it, and those who dealt directly with banks involved in setting LIBOR.

Deciding a figure for the potential liability facing banks is tough, partly because the cases will be testing new areas of the law such as whether, for instance, an Australian firm that took out an interest-rate swap with a local bank should be able to sue a British or American bank involved in setting LIBOR, even if the firm had no direct dealings with the bank. The extent of the banks’ liability may well depend on whether regulators press them to pay compensation or, conversely, offer banks some protection because of worries that the sums involved may be so large as to need yet more bail-outs, according to one senior London lawyer.

A particular worry for banks is that they face an asymmetric risk because they stand in the middle of many transactions. For each of their clients who may have lost out if LIBOR was manipulated, another will probably have gained. Yet banks will be sued only by those who have lost, and will be unable to claim back the unjust gains made by some of their other customers. Lawyers acting for corporations or other banks say their clients are also considering whether they can walk away from contracts with banks such as long-term derivatives priced off LIBOR.

The revelations also raise difficult questions for regulators. Mr Tucker’s involvement in the Barclays affair may harm his prospects of being appointed governor of the Bank of England, although he may well have a benign explanation for his comments (he is due to appear before parliament soon).

Another issue is the conflict central banks face, in times of systemic banking crises, between maintaining financial stability and allowing markets to operate transparently. Whether the BoE instructed Barclays to lower its submissions or not, regulators had a pretty clear motive for wanting lower LIBOR: British banks, in effect, were being shut out of the markets. The two hardest-hit banks, RBS and HBOS, were both far too big to fail, and higher LIBOR rates would have made the regulators’ job of supporting them more difficult.

This highlights a deeper question: what is the right level of involvement in influencing or regulating market interest rates, in a crisis, by those responsible for financial stability? Central banks get a slew of sensitive information from banks which they rightly do not want to make public. Data on deposit outflows at banks could trigger unnecessary runs, for example. Yet LIBOR is a measure of market rates, not those picked by policymakers.

Reform club

Two big changes are needed. The first is to base the rate on actual lending data where possible. Some markets are thinly traded, though, and so some hypothetical or expected rates may need to be used to create a complete set of benchmarks. So a second big change is needed. Because banks have an incentive to influence LIBOR, a new system needs to explicitly promote truth-telling and reduce the possibilities for co-ordination of quotes.

Ideas for how to do this are starting to appear. Rosa Abrantes-Metz of NYU’s Stern School of Business was one of a group of academics who, in 2009, raised the alarm that something fishy was going on with LIBOR. One simple change, she proposes, would be significantly to raise the number of banks in the panel. The theoretical changes needed to repair LIBOR are not difficult, but there are practical challenges to reform. The thousands of contracts that use it as a point of reference may need to be changed. Moreover, the real obstacle to change is not a lack of good ideas, but a lack of will by the banks involved to overturn a system that has served most of them rather well. With lawsuits and prosecutions gathering pace, those involved in setting the key rate in finance need to get moving. Adding a calendar note to “Fix LIBOR” just won’t do.

The LIBOR Scandal: The Rotten Heart Of Finance

‘This is undoubtedly the banking industry's tobacco moment,' says the chief executive of a multinational bank, referring to the lawsuits & settlements that cost America's tobacco industry more than $200 billion in 1998. 'It's that big.'

balls: the usual labour bullshit .....

Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls, called for a “root and branch” reform of British banking today following the revelations about the Libor rate fixing scandal that saw Bob Diamond step down last week as chief executive of Barclay’s Bank.

He also said the mooted £16m payoff for Diamond was "totally outrageous - it is off the scale.” He said it represented more than most people would ever earn in a lifetime. “The public will see it as shocking."

Appearing on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show this morning, Balls admitted that the last Labour government had been too lenient with its “light touch” regulation of the banking sector, and said it was now time to toughen up.

Balls reiterated the proposals put forward by Labour leader Ed Miliband in an interview with the Mail on Sunday, which praised him as "prescient" for denouncing "predator" banks months ago before the rate-fixing revelations.

Miliband told the paper he was disappointed with the coalition's decision not to launch a judge-led inquiry into banking in the style of the Leveson inquiry into media ethics, but said: "You win some, you lose some."

Now he is to launch proposals to radically reform banking. Miliband wants the UK's 'big five' high street banks to become a 'big seven' by selling up to 1,000 branches to two new privately run 'challenger banks'.

Labour believes the two new banks would create extra choice - and increased competition would lead to reduced charges for account holders. All banks would also be subject to new transparency rules, forced to reveal who they lend to, in the hope of ending discrimination against customers in deprived areas.

Miliband also wants a new regulatory body for bankers, in the style of the British Medical Association, with the power to strike off those found guilty of misdemeanours for life. He wants beefed-up fines and levies for badly-behaved banks to fund a huge increase in manpower and resources for the Serious Fraud Office.

The Labour leader also took the chance to back up his shadow chancellor over his recent acrimonious row with George Osborne, telling the Mail: "Osborne wants to play games, he made a whole lot of allegations against Ed Balls that aren’t true. Ed has told me they aren’t."

Labour Pushes For Root & Branch Reform Of British Banking

a toxic ecology .....

from the Drum ….

Barclays Bank's admission that they "fixed" money markets rates and JP Morgan's admission that so called hedges were "incorrect" are merely symptoms of a deeply compromised global financial system.

Significantly, even The Economist, sympathetic to capitalism and finance generally, resorted to the word "banksters". Something is rotten at the heart of global finance.

In his 1933 inauguration address, Franklin Delano Roosevelt attacked the "callow and selfish wrongdoing" in banking and business. Roosevelt told the crowd of over 100,000 that the "rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed" and that "unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion".

Some 80 years later, the money changers have not "fled their high seats in the temple of our civilisation". "Ancient truths" have not been restored to that temple. Something corrupt and rotten continues to fester at the heart of high finance, economic life and, indirectly, modern society.

Mr Smith Speaks...

On April 14, 2012, former Goldman Sachs executive director Greg Smith recorded a very public and sensational exit interview in the opinion pages of the New York Times.

The letter criticised "toxic and destructive" practices and cultures within Goldman Sachs, one of the world's largest and most important and influential investment banks.

The criticism focused on practices that exploited clients and put the interests of the bank first. It alleged a culture that was focused on getting clients to invest in securities or products that Goldman was interested in getting rid of.

The letter highlighted the use of complexity to confuse clients and the focus on highly profitable and (sometimes) unsophisticated clients who did not fully understand the risks of the transactions that they were being encouraged to enter into.

The most-noteworthy farewell speech since the film Jerry Maguire has been parsed as an expose of the alleged practices of his former employer. It is more subtle, highlighting a deeply flawed financial system as well as the poisonous and brutal culture of modern financial institutions.

Unfortunately, it is doubtful that it will follow the same trajectory as Frank Capra's 1938 film Mr Smith Goes to Washington, about a single honest man's effect on American politics.

Questioning Mr Smith...

Following publication, most press coverage focused on the use by Goldman Sachs staff of the term "Muppets" to describe clients.

In reality, the term is mild. In his book about his experiences at Morgan Stanley, former derivative salesman Frank Partnoy captured the relationship between bankers and their clients more colourfully: "The sell side [banks] hang up and say 'f*** you'! The buy side [clients] say 'f*** you!' and then hang up."

Mr Smith's primary concern - the failure of Goldman Sachs to give priority to the interest of its clients - appears naive. He ignored the firm's history, perhaps choosing to believe the statement of Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein that the firm does "God's work".

After the 1929 crash, a US Senate hearing investigated the Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation, a listed investment trust floated by the firm to its clients:

Senator Couzens: At what price [was it sold to the public]?

Mr Sachs: $104 ...

Senator Couzens: And what is the price of the stock now?

Mr Sachs: Approximately 1¾.

In June 1970, when Penn Central Transportation Company, the nation's largest railroad, defaulted on its debt, Goldman Sachs was found to have sold the company's debt to clients at face value when aware that the borrower's financial position was deteriorating.

The investment bank forced the company to buy back its own holding of Penn Central debt. None of Goldman Sachs' customers were made a similar offer.

In 2010, a Senate investigation and SEC action highlighted suspect practices surrounding the sale of mortgage-backed securities, known as the ABACUS and TIMBERWOLF, to "widows and orphans".

The firm paid a record $550 million fine to the US Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") to settle the allegations. In April 2012, Goldman Sachs paid $22 million to the SEC to settle charges that it allowed select clients to receive non-public information about stocks - a practice known as "huddles" or "Asymmetric Service Initiative".

In both transactions, Goldman Sachs appeared to display a familiar disregard for client interests.

Mr Smith appears not to have done proper due diligence on his employer. It is also surprising that it took him some 12 years to identify the problems of Goldman Sachs.

Mr Smith's personal motivation - stated as "a wake-up call to the board of directors" - is unclear.

The timing of his resignation in March 2012 was presumably to ensure that his bonus check cleared. It suggests that Mr Smith did not dislike the firm or its practices enough to give the money back.

The opinion piece reads like a job application. It recites Mr Smith's personal credentials - Stanford University (on a scholarship), a Rhodes Scholar finalist, a bronze medal for table tennis at the Maccabiah Games in Israel.

It also recites his professional achievements - advising clients with total assets of more than $1 trillion, including two of the largest hedge funds on the planet, five of the largest asset managers in the United States, and three of the most prominent sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East and Asia.

He fails to mention that his outburst may contravene non-disclosure and non-disparagement provisions in his employment contract.

With a book deal in the works, lucrative speaking opportunities, and even consulting to his old firm to address identified culture issues, Mr Smith's cri du coeur could be seen as an interesting career strategy at a time when anti-Wall Street sentiment is high and financial institutions are shrinking.

An interesting conflict...

Whatever Mr Smith's motivation, the accusations raise real issues, just not the ones being discussed. The central problem is the inbuilt conflict of interest in the current banking system between acting in the interest of a client and trading on the bank's own account.

In the 1990s, investment banking shifted from a client-focused business (providing advice, underwriting securities, and executing purchase and sales of financial instruments) to a business trading on the firm's own account using shareholder capital.

The change was driven by the growth in size and capital resources of investment banks, as they evolved from private partnerships into public companies or units of large commercial banks. It was also driven by shrinking margins on traditional activities, such as lower commissions and underwriting fees, and the need for new sources of revenue to meet investor return expectations.

Investment banks feared that the separation of client business and trading with its own capital would limit their ability to compete. Under CEO Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman Sachs embraced the conflict, emphasising intelligence from trading with clients and other banks to place bets with its own money.

Major investment banks sought to become "flow monsters", capturing a dominant proportion of trading volumes to assist their proprietary activities. To achieve this, banks used cross subsidies to attract certain clients. Execution or market-making and credit facilities to finance large hedge funds that were a source of significant trading volumes were provided at subsidised prices.

In an insidious process, this created pressure to increase trading volumes even further as well as increasing reliance on proprietary revenues to meet shareholder return targets.

The best research was channelled to support proprietary trading. Client research increasingly became devalued, evolving into mere puffery - a sales aid for selling products or the firm's inventory to the clients. Products were designed and sold to assist investment bank's proprietary traders to take positions, sometimes at the expense of clients unaware of the risks.

The shift was cultural as well as economic. In her 1999 book Goldman Sachs: The Culture of Success, Lisa Endlich, a former Goldman Sach employee on the trading side, makes snide comments about the "feeble and hidebound" traditional investment banking culture, with its focus on the client.

The trader culture, which Endlich celebrates, involves a transactional business model which is isolated from clients and highly results-oriented. Deals and profits dominate at the expense of client interests and relationships, a practice known as "scorched earth banking".

The success of the trading model can be seen from the fact that the path to the executive suite of an investment bank these days originates in the trading room. Both current Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein and his deputy Gary Cohn traded metals earlier in their banking careers.

Regulatory complicity...

Implemented in response to the 1929 stock market crash and the collapse of the banking system, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 sought to prevent some of these conflicts of interest, separating commercial banking from investment banking and limiting speculation. Removal of these regulations in the 1990s was crucial in allowing the development of the current banking model.

In the early 1990s, derivative scandals, such as Procter and Gamble, highlighted the problem. The internet stock boom exposed the practices of leading investment banks in relation to stock sales and self-serving research. But despite numerous enquiries, the problem was not addressed.

In 2002, America's Sarbanes-Oxley legislation failed to address the real issue - the inherent conflict of interest in integrated financial supermarkets combining commercial and investment banks.

In fact, legislators are rolling back some of the Sarbanes-Oxley provisions. The 2012 Jump-start Our Business Start-ups Act, shortened to JOBS, seeks to make it easier for companies to raise capital.

The bill would end the rule that investment banking analysts could not assist in marketing new issues of shares for new offerings, except those involving companies with sales of over $1 billion.

Investment banks, underwriting the issues, would not be prevented from making sales pitches or publishing research on a company during the initial public offering. The liability of investments banks will also be weakened.

New regulations, introduced following the financial crisis, do not also deal adequately with the problem. Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, known as the "Volcker rule", seeks to restrict the ability of regulated entities to undertake proprietary trading, indirectly regulating the identified conflict of interest.

The efforts of bank lobbyists have ensured that the final rule will be considerably weakened and riddled with exemptions. One lawyer told banks that "given so much of proprietary trading has a client nexus to it, I'll be embarrassed if I don't manage to exempt all your activities from the rule".

In the UK, the Vickers Report considered separation of certain activities of banks. In the end, the commission did not recommend radical reforms, proposing instead to force banks to ring fence UK retail operations rather than split along different business lines.

Unless the central conflict of interest is dealt with it, banks will always be tempted to give their own proprietary interests priority to boost earning. In reality, the only way to deal with this is by separation of client and proprietary activities.

Cruel finance...

The inherent conflicts of interest and a remuneration system based around short term revenues and bonuses create a toxic ecology within banking.

Financiers deride the real world and real people who move far too slowly. Only bankers know how to get things done. In her book Liquidated, ethnographer Karen Ho cites an interviewee:

We've made everyone smarter. We know much more…we're the grease that makes things turn more efficiently.

For bankers, this self-belief in their role and sense of superiority over clients justifies the ruthless and exploitative practices now embedded within finance.

In the 1970s, Pierre Bourdieu, a French sociologist and anthropologist, introduced the concept of habitus - the idea that each society and culture orders its world subconsciously according to a cognitive framework based on its experiences.

In the 16th century, the Spanish conquistadors who conquered the New World brought the ambitions, prejudices, attitudes and values of their culture. Their success shaped their habitus.

Achievements were validated with riches, rank and power. Failures brought disease and death, mollified by the consolations of faith and the afterlife.

The financial elite now undertake similar conquest and plunder with scientific and economic pretensions. The Masters of Universe strut through the City of London, Wall Street, the Bahnofstrasse, Finanzplatz Deutschland, Raffles Place and Tokyo's Marunouchi like god but in a better suit.

In his books and essays, sociologist Zygmunt Bauman uses the metaphors of liquid and solid modernity to capture the shift from a society of producers to a society of consumers. Security gives way to increased freedom to purchase, to consume and to enjoy life.

In liquid modernity, social forms and institutions no longer have time to solidify into accepted frames of reference for human actions and long-term plans. Individuals have to be flexible and adaptable, pursuing available opportunities.

Liquid modernity requires calculation of likely gains and losses of acting (or failing to act) under endemic uncertainty. The readiness to discard extends to people who we do not recognise as fellow human beings - migrant workers, immigrants, terrorist suspects or, in banking, clients: "It seems all things, born or made, human or not, are until-further-notice and dispensable."

Karen Ho in Liquidated documented the brutal culture of modern banking. Hired as the best and brightest and expecting royal treatment, graduates work like indentured slaves for up to 140 hours a week.

In a brutal world without job security and where performance is constantly assessed, bankers survive by trading things or cutting deals. Ho's title evokes Bauman's idea of liquid modernity. Bankers make assets liquid or tradable. As highly liquid assets themselves that could be easily liquidated, they live in constant fear.

For bankers, the environment is challenging, where they must adapt or die. There is an old Wall Street saying: "Never tell anyone on Wall Street your problems. Some don't care. Most are glad you have them."

In their work, John Lennon's song Working Class Hero provides the survival script:

There's room at the top they are telling you still/ But first you must learn how to smile as you kill/ If you want to be like the folks on the hill.

These forces created a culture where narrow, short-term self-interest dominates. The culture drives creation and sales of products of no intrinsic value to people who do not understand them. Fear of being liquidated eliminates misgivings about profitable transactions that might result in enormous pain for others.

Bernard Madoff preyed upon unwitting members of his religious and ethnic communities, enlisting leading figures to help promote fraudulent investments as legitimate. Pink Floyd had sung about it in Dogs:

You have to be trusted by the people that you lie to/ So that when they turn their backs on you/ You get the chance to put the knife in.

Financial nihilism...

In a famous series of experiments delivering electric shocks to people, Stanley Milligram found that:

Ordinary people can become agents in a terrible destructive process... . Even when the destructive effects of their work becomes patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

In the last 20 years, bankers have become willing agents in a highly destructive process, even when they were aware of the consequences of the action. They are unable or unwilling to resist the peer pressures and ultimately the lure of wealth.

It is as Marcel Proust wrote in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu:

… indifference to the sufferings one causes, an indifference which whatever other names one may give to it is the permanent form of cruelty.

Greg Smith's statement does not merely point to questionable behaviours at the investment bank, once tagged by Rolling Stones journalist Matt Taibbi as "a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money".

As recent events highlight again, the alleged practices are widespread throughout the industry, where competitors ironically see Goldman Sachs as a role model. They are also the result of a deeply flawed and dangerous business model and culture which is poorly understood and rarely challenged.

Satyajit Das is author of Traders Guns & Money and Extreme Money. View his full profile here.

Something Rotten At The Heart Of High Finance

surprise, surprise .....

Oil prices are likely to have been rigged in the same way as the Libor rate, forcing drivers to pay more for petrol, according to a G20 report. MPs are now calling for the inquiry into Barclays' manipulation of the Libor interbank lending rate to be expanded to petrol prices.

Petrol prices on UK forecourts reached a record high of 137p per litre earlier this year before falling back slightly.

The price drivers pay to fill their tanks is linked to the cost of oil, which is calculated by two main price reporting agencies, Platts and Argus, based on data collected from banks, hedge funds and oil companies.

The G20 report, compiled by the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), found that because the companies collecting this data rely on the honesty of traders, and because these traders have an "incentive" to distort the market, the oil price is open to "manipulation".

US regulators have already highlighted the likelihood that oil prices might have been fixed, The Daily Telegraph reports. Commissioner Scott O'Malia of the US Commodity Trading Commission has spoken of the "striking similarity" between price reporting agencies in the oil market and Libor.

Robert Halfon, the Conservative MP for Harlow who with 100 fellow MPs has campaigned for lower petrol prices, said the Bank of England must investigate potential manipulation "urgently".

The Petrol Retailers' Association has also supported an inquiry, saying:

"All the petrol retailers buy their products based on Platts prices. If IOSCO thinks the price is open to manipulation it could well be and that would affect prices on the forecourts."

However, Platts and Argus have hit back, highlighting "fundamental differences" in the way they calculate oil prices and the way Libor is estimated. In a joint statement, the companies said: "Independent price reporting organisations are independent of and have no vested interest in the oil and energy markets."

Petrol Prices Might Have Been Fixed Same Way As Libor

back at the checkout .....

Barclays continues to dominate the headlines. It turns out the top man responsible for ordering the submission of false information to Libor, Jerry del Missier, left with £8.75m when he quit the bank earlier this month.

At the same time, Barclays is having to deal with the revelation that some of its senior American executives have been fundraising for Republican candidate Mitt Romney when, as MPs put it, they should have been working to rebuild public trust in the bank.

The £8.75m payoff:

It appears Del Missier negotiated the severance package with chairman Marcus Agius soon after the Libor scandal broke. It meant that he left with four times as much as his boss Bob Diamond, who left the bank the same day.

The £8.75m represented half of a £17m long-term bonus which had matured in March. At that time, Del Missier "was asked to defer receipt of the award because it was seen as an inappropriate time for such a lavish payout", The Times reports.

According to City sources, Barclays felt it had no legal argument to deny Del Missier the money on the day he left.

The pay-out "looks certain to trigger another political storm over bankers' pay", says The Daily Telegraph. George Mudie, a Labour member of the Treasury select committee, says the revelation makes any claims that Barclays is determined to change its culture and behave more acceptably look "shallow".

The fundraising:

A vice-chairman at Barclays has written to MPs saying the bank is non-partisan and any political donations are made by employees in a personal capacity.

It follows last week's Early Day Motion, signed by 11 MPs, demanding the bank and its directors "stop working to bolster Romney's election campaign war chest and concentrate on repairing confidence and trust in the banking system instead," as The Guardian puts it.

Barclays US executives have already raised $1m for Romney and are expected to be among the many international bankers at a fundraising dinner in Mayfair tonight, to be attended by the candidate. Tickets cost between $50,000 and $75,000.

Vice-chairman Cyrus Ardalan has written to the MPs saying: "All political activity undertaken by Barclays' US employees, including personal fundraising for specific candidates, is done so in a personal capacity, and not on behalf of Barclays."

New Storm Over £8.75m Payout For Barclays’ Jerry-del-Missier

the partial end of the affair...

(Gus note: the total GDP of all the countries on this planet is less than 100 trillion per annum...The entire "game" of derivatives is worth more than 1500 trillions or five times the Libor controlled funds)

The banks are supposed to submit the actual interest rates they are paying, or would expect to pay, for borrowing from other banks. The Libor is supposed to be the total assessment of the health of the financial system because if the banks being polled feel confident about the state of things, they report a low number and if the member banks feel a low degree of confidence in the financial system, they report a higher interest rate number. In June 2012, multiple criminal settlements by Barclays Bank revealed significant fraud and collusion by member banks connected to the rate submissions, leading to the scandal.[5][6][7]

Because Libor is used in US derivatives markets, an attempt to manipulate Libor is an attempt to manipulate US derivatives markets, and thus a violation of American law. Since mortgages, student loans, financial derivatives, and other financial products often rely on Libor as a reference rate, the manipulation of submissions used to calculate those rates can have significant negative effects on consumers and financial markets worldwide.

On 27 July 2012, the Financial Times published an article by a former trader which stated that Libor manipulation had been common since at least 1991.[8] Further reports on this have since come from the BBC[9][10] and Reuters.[11] On 28 November 2012, the Finance Committee of the Bundestag held a hearing to learn more about the issue.[12]

The British Bankers' Association (BBA) said on 25 September 2012 that it would transfer oversight of Libor to UK regulators, as predicted by bank analysts,[13] proposed by Financial Services Authority managing director Martin Wheatley's independent review recommendations.[14] Wheatley's review recommended that banks submitting rates to Libor must base them on actual inter-bank deposit market transactions and keep records of those transactions, that individual banks' LIBOR submissions be published after three months, and recommended criminal sanctions specifically for manipulation of benchmark interest rates.[15] Financial institution customers may experience higher and more volatile borrowing and hedging costs after implementation of the recommended reforms.[16] The UK government agreed to accept all of the Wheatley Review's recommendations and press for legislation implementing them.[17]

Significant reforms, in line with the Wheatley Review, came into effect in 2013 and a new administrator took over in early 2014.[18][19] The UK controls Libor through laws made in the UK Parliament.[20][21] In particular, the Financial Services Act 2012 brings Libor under UK regulatory oversight and creates a criminal offence for knowingly or deliberately making false or misleading statements relating to benchmark-setting.[18][22]

As of November 2017, 13 traders had been charged by the UK Serious Fraud Office as part of their investigations into the Libor scandal. Of those, eight were acquitted in early 2016.[23][24][25] Four were found guilty (Tom Hayes, Alex Pabon, Jay Vijay Merchant and Jonathan James Mathew)[26], and one pleaded guilty (Peter Charles Johnson).[27] The UK Serious Fraud Office closed its investigation into the rigging of Libor in October 2019 following a detailed review of the available evidence.[28]

-------------------

On 16 April 2008, The Wall Street Journal released an article, and later study, suggesting that some banks might have understated borrowing costs they reported for the Libor during the 2008 credit crunch that may have misled others about the financial position of these banks.[30][31] In response, the BBA claimed that the Libor continued to be reliable even in times of financial crisis. Other authorities contradicted The Wall Street Journal article saying there was no evidence of manipulation. In its March 2008 Quarterly Review, the Bank for International Settlements stated that "available data do not support the hypothesis that contributor banks manipulated their quotes to profit from positions based on fixings."[32] Further, in October 2008, the International Monetary Fund published its regular Global Financial Stability Review which also found that "Although the integrity of the U.S. dollar Libor-fixing process has been questioned by some market participants and the financial press, it appears that U.S. dollar Libor remains an accurate measure of a typical creditworthy bank's marginal cost of unsecured U.S. dollar term funding."[33]

Read more:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libor_scandal

——————————————

The Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the British equivalent of the French National Financial Prosecutor's Office, has just finalised the (Euro-side of the) Libor case, one of the major financial court cases of the past decade. On June 10, it discreetly abandoned the European arrest warrant for four ex-traders Stéphane Esper, a former Societe Generale member, Joerg Vogt, Ardalan Gharagozlou and Kai-Uwe Kappauf, three former Deutsche Bank alumni .

This epilogue concludes a dossier that has gradually deflated for the SFO. Originally presented as a major scandal of financial manipulation, it ends with four convictions out of the eleven people initially prosecuted, and the impression that the case was less serious than it seemed at first glance.

A bitter taste

The abandonment of the four European arrest warrants will no doubt leave a bitter taste for the traders who had agreed to answer to British justice. In early 2016, the latter summoned the eleven accused for a preliminary hearing. Five of them, based outside the United Kingdom, then refused to appear. The other six, while claiming their innocence, agree to appear. Among them were two Frenchmen, Christian Bittar and Philippe Moryoussef, who came from Singapore, where they were then stationed, to defend themselves in person.

For the future of the accused, the decision to appear that day will change everything. British justice issues European arrest warrants against the absent. Normally, this is a simple formality. But the French and German courts were quarreling. They did not understand what the traders were charge with or for — or believed that the facts, dating from 2005 to 2010, were prescribed. In all cases, they blocked extraditions. Consequently, these five traders would no longer worry, as long as they remain in their country (one of them was arrested during a stay in Italy, extradited to the United Kingdom, where he won his trial).

The abandonment of the arrest warrant against them on June 10 [2020] ends this aspect of the case.

Read more:

https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2020/06/22/affaire-euribor-abandon-des-poursuites-contre-quatre-ex-tradeurs_6043726_3234.html

Read from top.