Search

Recent comments

- poisoned dart?....

3 hours 11 min ago - narrative control....

7 hours 18 min ago - chabad....

12 hours 33 min ago - back to the kitchen....

12 hours 36 min ago - loneliness....

14 hours 45 min ago - insight....

15 hours 16 min ago - conspiracy....

1 day 11 hours ago - brutal USA....

1 day 12 hours ago - men....

1 day 13 hours ago - oil....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

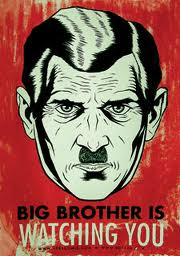

fascism's handmaiden ....

Attorney-General Nicola Roxon appears to have swung her support behind a controversial plan to capture the online data of all Australians, despite only six weeks ago saying ''the case had yet to be made'' for the policy.

The data retention plan - which would force all Australian telcos and internet service providers to store the online data of all Australians for up to two years - is the most controversial element of a package of more than 40 proposed changes to national security legislation.

If passed, the proposals would be the most significant expansion of national security powers since the Howard-era reforms of the early 2000s.

In a speech to be delivered at the Security in Government conference in Canberra today, Ms Roxon will say that law enforcement agencies need the data retention policy in order to be able to effectively target criminals.

''Many investigations require law enforcement to build a picture of criminal activity over a period of time. Without data retention, this capability will be lost,'' she will say, in a draft of the speech provided to Fairfax Media yesterday.

She will also say technological advancement since the advent of the internet is providing increasing room to hide for criminals and those who threaten Australia's security.

''The intention behind the proposed reform is to allow law enforcement agencies to continue investigating crime in light of new technologies. The loss of this capability would be a major blow to our law enforcement agencies and to Australia's national security."

But in an interview with Fairfax Media in mid July, Ms Roxon appeared to have a different view. ''I'm not yet convinced that the cost and the return - the cost both to industry and the [privacy] cost to individuals - that we've made the case for what it is that people use in a way that benefits our national security,'' she said.

''I think there is a genuine question to be tested, which is why it's such a big part of the proposal.''

Her apparent change of mind may be a result of conversations with the Australian Federal Police, who have long pushed for mandatory online data retention. Neil Gaughan heads the AFP's High Tech Crime Centre and is a vocal advocate for the policy.

''Without data retention laws I can guarantee you that the AFP won't be able to investigate groups such as Anonymous over data breaches because we won't be able to enforce the law,'' he told a cyber security conference recently.

But Andrew Lewman, the executive director of the Tor software project, which disguises a person's location when surfing the web, challenges that view. In July he told Fairfax Media data retention impedes the effectiveness of law enforcement.

''It sounds good and something sexy that politicians should get behind. However, it doesn't stop crime, it builds a massive dossier on everyone at millisecond resolution, and creates more work and challenges for law enforcement to catch actual criminals.

''The problem isn't too little data, the problem is there is already too much data.''

Proposals 'characteristic of a police state'

The proposals are being examined by the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Intelligence and Security to provide partial scrutiny of Australia's intelligence community.

The committee has thus far received almost 200 submissions from the agencies, members of the public as well as civil liberties and online rights groups.

In a heated submission to the inquiry, Victoria's Acting Privacy Commissioner, Anthony Bendall, dubbed the proposals ''characteristic of a police state'', arguing that data retention in particular was ''premised on the assumption that all citizens should be monitored''.

''Not only does this completely remove the presumption of innocence which all persons are afforded, it goes against one of the essential dimensions of human rights and privacy law: freedom from surveillance and arbitrary intrusions into a person's life."

ISP iiNet said government had failed to demonstrate how current laws were failing or how criminals and terrorists posed a threat to networks, and said asking carriers to intercept and store customers' data for two years could make them ''agents of the state'' and increase costs.

A joint submission from telco industry groups argued it would cost between $500 million and $700 million to keep data for two years. It called for full compensation from the government's security agencies.

The Australian Federal Police and the Australian Taxation Office were among the few supporting the proposal to retain telecommunications data.

The ATO said the proposal would be consistent with European practices and that being able to access real-time telecommunications data would allow it to ''respond more effectively'' to attempts to defraud the Commonwealth.

The AFP, in its submission, said interception capabilities were increasingly being ''undermined'' by fundamental changes to the telecommunications industry and communications technologies. It said telco reform was needed "in order to avoid further degradation of existing capability".

Through the use of case studies, the AFP argued that on numerous occasions it had been restricted by what it could do under current telecommunications laws, and said that many offences went un-prosecuted because of this.

Costs may be passed on to consumers

The AFP conceded that the volume of data and its retention by telcos for use as evidence for agencies presented "challenges", but didn’t disclose how such challenges could be tackled.

Such challenges were highlighted in submissions by others like Victoria's Acting Privacy Commissioner Anthony Bendall. He said smaller ISPs, for instance, "may not be able to afford the data storage costs, and these costs may be passed on to consumers".

"It would appear that public support for this type of proposal is largely absent," Bendall said.

Users may abandon web

Bendall also said that data retention could "create an extreme chilling effect" not only on technology but on social interactions, many of which are now conducted solely online.

"Users may move away from using online services due to the fear that their communications are being monitored," he said. "Simply put, the proposal could mean that individuals, due to concerns about surveillance, revert back to offline transactions.

"If this occurred, it would affect existing efficiencies of both businesses and government," he said.

The Australian Privacy Foundation was just as scathing.

"Too many of the proposals outlined ... would herald a major and unacceptable increase in the powers of law enforcement and national security agencies to intrude into the lives of all Australians," the APF said.

The APF said the discussion paper released with the proposals was "misleading, and probably intentionally so".

Fears for journalist's sources

It’s not just privacy advocates and telcos that expressed concern with the proposals, but the journalist union, the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance. In its submission it said it was concerned that any expansion of interception powers and the powers of intelligence agencies had "the potential to threaten press freedom".

"There is considerable concern about the power of police and intelligence agencies to intercept communications, a concern not given proper consideration in the terms of reference," the MEAA said.

Online users' lobby group Electronics Frontiers Australia raised similar concerns to others but pointed out that one of the 40 proposed changes to national security legislation, which required people to divulge passwords, could lead to self-incrimination. It said should such a law be enacted it would undermine "the right of individuals to not co-operate with an investigation".

The lobby group also highlighted concerns with another proposal which would allow the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation to use an innocent person's computer to get into a suspect's computer. "The proposal that ASIO would be permitted to 'add, delete or alter data or interfere with, interrupt, or obstruct the lawful use of a computer' could lead to some very serious consequences," it said.

Such consequences could include, it said, pollution of evidence, potentially leading to failures of convictions. It could also provide the means for evidence to be "planted" on innocent parties, it said.

Roxon Edges Toward Keeping Online Data For Two Years

What a pathetic joke these people are.

No-one in Australia needs any special intelligence to know that we are ripped-off daily by criminals in business suits: from bankers, to lawyers, the medical profession, the churches, the media to politicians.

Our institutions from Duntroon to the Reserve Bank, to the AFP & ASIO, are corrupted from top to toe, whilst drug peddlars & scam artists of all persuasions ply their trade.

Ordinary workers are victimised by the organisations that are supposed to be protecting them, whilst their officials line their own pockets.

And no-matter how obvious the crime, nothing is done about it.

If this dopey woman thinks that giving more power to the AFP & ASIO will change any of this, she is a lot dumber than she looks.

This country has been betrayed by politicians who were entrusted with the task of protecting it & the rights & freedom of its citizens.

Disgusting.

- By John Richardson at 4 Sep 2012 - 9:37am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

roxon rocks on regardless ....

from Crikey …..

Roxon clarifies draconian data retention plans

Crikey Canberra correspondent Bernard Keane writes:

ASIO, DATA RETENTION, JOINT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY, NICOLA ROXON, US NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY

Attorney-General Nicola Roxon has responded to growing complaints about the ill-defined nature of the data retention proposals currently being considered by the Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security by releasing a five-page "clarifying letter".

As Crikey reported this week, committee members such as Labor elder John Faulkner have joined key stakeholders in criticising the vague nature of some of the proposals, and particularly the extremely limited nature of the information on data retention.

On Wednesday, Roxon wrote to committee chairman Anthony Byrne to "clarify the parameters of this proposal", while insisting she does not have a specific model in mind. However, the letter discusses in detail the European Union's data retention directive of 2006, suggesting that if Roxon doesn't have a specific model in mind she's doing a fair impression of it.

In the Attorney-General's Claytons' model, no content data of any kind would be retained, and not, seemingly, URLs of sites visited by an IP address, although this point is made less clearly in the letter than in her previous public statements. "The government does not propose that a data retention scheme would apply to the content of communications. The content of communications may include the text or substance of emails, SMS messages, phone calls or photos and documents sent over the internet," Roxon says in the letter.

ASIO, whose unclassified submission was recently revealed by JCIS, similarly cites the EU directive.

But the EU data directive that Roxon cites has come in for extensive criticism. Several EU states have refused to apply it, insisting it's unconstitutional. In 2010, the German Federal Constitutional Court annulled the German law implementing it and the German government has failed to replace it since then. Also in 2010, following an extended review, EU privacy officials released a scathing report on the directive which found that some service providers were keeping records of URLs and email headers, mobile phone data on the location of users was being retained and that reporting on compliance was poor. The EU is now reviewing the directive with the aim of overhauling it at the same time as its e-privacy directive.

The EU model is also at odds with the model argued for by the AFP, which has appeared to lobby for the retention of URLs to enable it to pursue child abusers. According to industry sources, the previous model put forward by the Attorney-General's Department in secret consultations with telcos and ISPs was significantly closer to the wide-ranging model favoured by law enforcement.

There are two things to bear in mind about Roxon's Claytons' data retention model: it is still, as several European courts have found, a serious assault on the right to privacy, not the least because even a limited retention model confined to telecommunications data can enable extensive profiling of the user of an IP address. Moreover, as the EU privacy report makes clear, implementation of an Australian data retention directive would be in the hands of private companies whose adherence to the letter of the law on what is to be retained would be influenced by cost and human error.

The other is that data retention is only one of a range of draconian proposals put forward by AGD: confusion, not least between what the discussion paper says and what the Attorney-General herself has said, continues about the proposal to criminalise refusal to assist with decryption; wiretapping social media usage is also on the agenda, as is giving ASIO and the AFP the green light to plant software on computers. With all the focus on data retention, there's a real risk other proposals won't receive the attention they merit.

trust who ....

from Crikey ….

the myths around surveillance

The inquiry currently under way by Parliament's Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security into more than 40 proposals to extend the surveillance, intelligence-gathering and enforcement powers of our law enforcement and security agencies has seen a number of myths peddled by proponents of still-greater powers to intrude on Australians' privacy and basic rights.

A persistent one is the suggestion that Australia's laws governing surveillance and intelligence-gathering are desperately in need of updating, that they have lain untouched since the technological pre-history of 1979, when the internet was the dream of a few American scientists and academics. In evidence to the Committee yesterday from some of Australia's most senior policemen, we again heard how laws written in 1979 have been overtaken by technology.

It's a seductive argument, isn’t it? Technology has moved on, we’ve shifted our communications online - why not just allow what the state used to be able to do with phones, with the internet?

That's misleading, of course - we live, work, communicate, have relationships and engage socially and politically far more online than we ever did on the phone.

But where the argument falls down first is that the laws haven't been overtaken by technology. The laws about surveillance have been routinely updated. According to the Parliamentary Library, there have been 45 separate amendments to the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 since September 2001 alone.

A number have been trivial - changing "chairman" to "chair", for instance. But others created new offences that could be used to justify wiretapping, and as long ago as 2004, cybercrime was included in the framework. Far from being an outdated framework, our surveillance laws are in rude health and have been regularly extended to suit the demands of law enforcement.

Apparently, though, law enforcement agencies always want more power, no matter how much they're given.