Search

Recent comments

- MAGA fools

8 hours 36 min ago - the ugliest excuse to go to war.....

18 hours 47 min ago - morons....

20 hours 39 min ago - idiots...

20 hours 40 min ago - no reason....

21 hours 46 min ago - ask claude...

1 day 1 hour ago - dumb blonde....

1 day 8 hours ago - unhealthy USA....

1 day 9 hours ago - it's time....

1 day 9 hours ago - pissing dick....

1 day 9 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

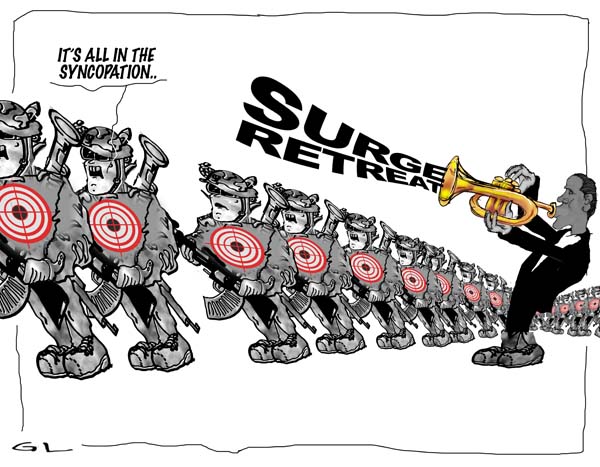

back in 2009...

surge

surge

ON THE AFTERNOON of October 9, 2009, President Barack Obama met with his top generals, Cabinet officials, and his vice president to hash out strategy for the war in Afghanistan. Earlier that morning, Obama learned he’d been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The war in Afghanistan was now eight years old, and Obama had campaigned on the idea that the Bush administration’s effort there had been headed in the wrong direction.

By Ryan Grim at The Intercept

Gens. Stanley McChrystal and David Petraeus, along with much of the military brass, were pushing for a troop increase of 40,000 to 85,000 in Afghanistan. Doing so would allow for a counterinsurgency strategy, they claimed, and would give the Americans time to recruit and train a larger Afghan national army and police force. The pivotal meeting is captured in Bob Woodward’s 2010 book “Obama’s Wars.”

Advocates for an expanded war found their most nettlesome opponent in Joe Biden.

“As I hear what you’re saying, as I read your report, you’re saying that we have about a year,” Biden said to McChrystal. “And that our success relies upon having a reliable, a strong partner in governance to make this work?”

McChrystal said yes, that was the case. Biden turned to Karl Eikenberry, a former general who was now ambassador to Afghanistan. “In your estimation, can we, can that be achieved in the next year?”

Eikenberry told Biden no, it was not possible, because there was no strong, reliable partner in Afghanistan. Eikenberry followed with a pessimistic 10-minute assessment of the situation and pinpointed another logical failure that would manifest itself more than a decade later. “We talk about clear, hold and build, but we actually must include transfer into this,” Eikenberry said, adding that to eventually withdraw, the transfer was key.

Eikenberry said he “would challenge [the] assumption” that the U.S. and the Afghan government were even aligned. “Right now we’re dealing with an extraordinarily corrupt government,” he said.

Petraeus, when he spoke, acknowledged what had become obvious. “I understand the government is a criminal syndicate,” he said. “But we need to help achieve and improve security and, as noted, regain the initiative and turn some recent tactical gains into operational momentum,” Petraeus said, adding that he “strongly agreed” with McChrystal’s pitch for a larger force.

Biden cut in: “If the government’s a criminal syndicate a year from now, how will troops make a difference?” he asked.

Biden was getting at something fundamental: Did anybody believe what the generals were proposing was actually possible? Biden’s questions were largely ignored by the war planners, but the conversation held in that meeting makes clear that the answer was readily available by 2009: It was not possible and would collapse quickly once U.S. support was withdrawn. Instead of following Biden’s lead, the Obama administration allowed the carnage to drag on fruitlessly for another 12 years.

Woodward’s next lines are the most telling: “No one recorded an answer in their notes. Biden was swinging hard at McChrystal, [Defense Secretary Bob] Gates and Petraeus.”

Biden pressed on. “What’s the best-guess estimate for getting things headed in the right direction? If a year from now there is no demonstrable progress in governance, what do we do?”

Again, no answer.

Again, Biden asked: “If the government doesn’t improve and if you get the troops, in a year, what would be the impact?”

Finally, Eikenberry responded. “The past five years are not heartening,” he said, “but there are pockets of progress. We can build on those.” In the next six to 12 months, he added, “We shouldn’t expect significant breakthroughs.”

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, said that the dilemma was whether to focus on adding troops or better governance. “But not putting troops in guarantees we won’t achieve what we’re after and guarantees no psychological momentum. Preventing collapse requires more troops, but that doesn’t guarantee progress.” She added, “The only way to get governance changes is to add troops, but there’s still no guarantee that it will work.”

Richard Holbrooke, special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, chimed in with a reality that was largely kept from the U.S. public. “Our presence is the corrupting force,” Holbrooke said. Woodward then paraphrased his explanation: “All the contractors for development projects pay the Taliban for protection and use of roads, so American and coalition dollars help finance the Taliban. And with more development, higher traffic on roads, and more troops, the Taliban would make more money.”

He added that the numbers were all fake, noting that he had sent staff to investigate the claims being made by contractors that they had trained a massive number of Afghan police. About 80 percent of the force was illiterate, he said, drug addiction was common, and that was for the police officers who actually existed. Many, he said, were “ghosts” who got paychecks but never showed up.

He said that with a 25 percent attrition rate, McChrystal’s projections for the growth of Afghan forces was mathematically impossible. “It’s like pouring water into a bucket with a hole in it,” Holbrooke said.

Holbrooke’s argument is largely paraphrased by Woodward because, known as somebody willing to speak uncomfortable truths in high-level meetings, he was somebody the other officials had simply begun to ignore. Wrote Woodward: “Several note takers had learned to do the same thing when Holbrooke embarked on his discourse. They set down their pens and relaxed their tired fingers. The big personality had lost its sheen. He was not connecting with Obama.”

Biden’s summation, said Woodward, returned to the theme that the project was doomed due to the failure to have built a real Afghan government. Obama thanked his advisers for getting him closer to a decision. On December 1, he announced publicly he’d be surging 40,000 new troops into Afghanistan, while preparing for an exit. The surge came, but it was left to Biden to finally lead the way out.

Read more:

https://theintercept.com/2021/09/02/afghanistan-obama-war-biden/

Cartoon at top c 2009 by Gus Leonisky...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 7 Sep 2021 - 5:47pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

addicts won't be happy...

From James O’Neill

After 40 years the United States occupation of Afghanistan has finally ended. I say 40 years because their involvement in the country began in response to the Soviet occupation which began in 1980. The United States supported the mujahedin fighters who opposed the Soviet occupation and never really stopped, even after the Soviets withdrew in 1989. Contrary to American expectations the government of Afghanistan lasted for a further three years.

It was entirely consistent with the United States view of the world but they could not just leave Afghanistan in 2021, but had to leave a trail of destruction behind them. The facilities which made Kabul airport functional were all destroyed. To call the wanton destruction vindictive would be an understatement.

It is well known that the withdrawal from Afghanistan was far from being a universally approved United States decision. There were, and are, strong forces that continue to insist that the decision was wrong. An element of this resistance was self-interest. The United States stands to lose a significant source of illicit income if the Taliban repeat the 1990 policy of destroying the poppy fields.

At the time of the United States invasion in 2001 the poppy fields, source of the heroin that reeks such carnage upon the world, less than 5% of the original poppy fields production remained, existing almost exclusively in the territory that the Taliban failed to control. Now, they effectively control more than 95% of Afghanistan territory, and the small pocket remaining is not known for its ability to grow poppies.

Both the Russian and Chinese government, who have already approached the new regime in Kabul, are making it clear that they expect the Taliban to pursue a similar policy of non-tolerance towards the growing of the poppy and with it the production of what, this year, amounted to more than 90% of the world heroin production.

It has been notable that the western media has almost totally ignored the production of the poppies and with it the supply of heroin in their discussions about the implications of the United States withdrawal. It is not too difficult to realise the reason for this silence. The western media have long subscribed to the view that the United States involvement in Afghanistan was a “democracy building” exercise.

Acknowledging that being the world’s largest supplier of heroin did not fit with the altruistic image the West endeavoured to portray. Almost entirely missing from the western media portrayal of the invasion was the fact that one of the earliest consequences of the United States 2001 invasion was a rapid escalation of poppy production and hence heroin supply. Equally missing from the western narrative was the fact that this production was almost exclusively a United States enterprise, firmly in the hands of the CIA, not only in production, but in the processing of the raw poppy into heroin, and its subsequent distribution around the world. As such it remained a significant contributor to CIA illicit funds, used in turn as part of their worldwide program of influencing governments of multiple countries.

Three of those countries that suffered as a consequence of this heroin epidermic are China, Iran and Russia. It is little surprise therefore that a condition of the support of these three countries to the new Taliban government is a renewal of the latter’s implacable dislike of heroin when they were last in power. The western media have been almost completely silent on the new Afghanistan government’s views on the topic. But there is little reason to believe that their hostility is in any way reduced from when they were last in power.

The control of production has been under the oversight of the many thousands of United States contractors, i.e. mercenaries. Again, the western media have been remarkably quiet about the fate of these thousands of persons who were not part of United States withdrawal plans and presumably remain in place. How long that will persist under the new government is an open question, but they are unlikely to be allowed to remain for very much longer. The local warlords, with whom they cooperated in the production of heroin similarly have a short life expectancy. They are expected to continue to resist the Taliban takeover, but it seems a doomed resistance.

The Imminent destruction of the poppy crop raises the obvious question of its replacement. There are a few places in the world suitable for the growing of a significant crop of poppies to feed the industry. The growers have been largely excluded from the previous production areas of Indochina and the Chinese government is unlikely to tolerate a renewal of that crop any time soon.

The absence of an alternative source of poppy production is likely to create a worldwide problem with addicts being denied their source of supply. Dealing with the effects of the deprivation of supply will create a significant treatment problem for, among others, the governments of Pakistan and Iran, both of whom have seen escalation of addiction in recent years.

In the longer term, coping with the problems of addicts deprived of the supplies are a lesser problem than coping with ever growing numbers of addicts. It may be therefore, that one of the major benefits of the United States forced withdrawal from Afghanistan will be a reduction in the global pandemic of heroin addiction. Not too many tears will be shed for the demise of this appalling trade whose growth and flourishing in recent years should be laid squarely at the door of the Americans. Western media reluctance to discuss this fact should not detract from its importance.

James O’Neill, an Australian-based former Barrister at Law, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

Read more:

https://journal-neo.org/2021/09/07/the-demise-of-the-heroin-trade-a-major-benefit-of-the-us-defeat-in-afghanistan/

See also:

FREEING JULIAN ASSANGE would be a good start...