Search

Recent comments

- "CIA"....

4 hours 24 min ago - provoked....

4 hours 32 min ago - war footing....

4 hours 41 min ago - vote....

4 hours 56 min ago - don't relax....

5 hours 41 min ago - 1939–1945....

6 hours 24 min ago - no time?....

6 hours 38 min ago - framing....

10 hours 33 min ago - huckabee v tucker.....

10 hours 48 min ago - EU degeneration....

11 hours 36 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

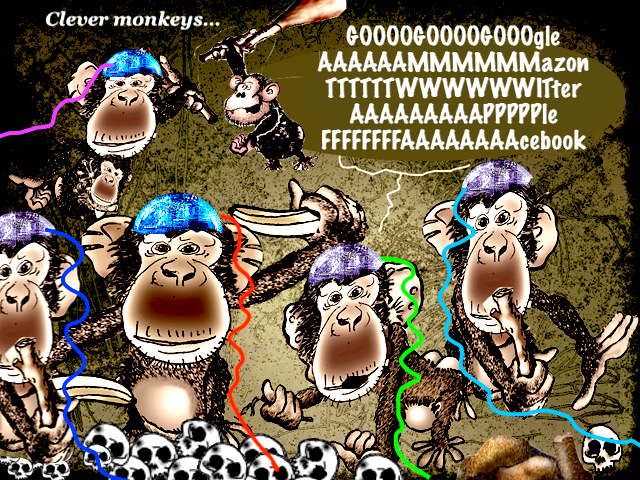

how we are made to think by the big tech….

Author and law professor Maurice Stucke explains why the practices of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple are so dangerous and what’s really required to rein them in. Hint: Current proposals are unlikely to work.

Google. Amazon. Facebook. Apple. We live within the digital worlds they have created, and increasingly there’s little chance of escape. They know our personalities. They record whether we are impulsive or prone to anxiety. They understand how we respond to sad stories and violent images. And they use this power, which comes from the relentless mining of our personal data all day, every day, to manipulate and addict us.

University of Tennessee law professor Maurice Stucke is part of a progressive, anti-monopoly vanguard of experts looking at privacy, competition, and consumer protection in the digital economy. In his new book, Breaking Away: How to Regain Control Over Our Data, Privacy, and Autonomy, he explains how these tech giants have metastasized into “data-opolies,” which are far more dangerous than the monopolies of yesterday. Their invasion of privacy is unlike anything the world has ever seen but, as Stucke argues, their potential to manipulate us is even scarier.

With these four companies’ massive and unprecedented power, what tools do we have to effectively challenge them? Stucke explains why current proposals to break them up, regulate their activities, and encourage competition fall short of what’s needed to deal with the threat they pose not only to our individual wallets and wellbeing, but to the whole economy — and to democracy itself.

Lynn Parramore: The big firms that collect and traffic in data — “data-opolies” you call them – why do they pose such a danger?

Maurice Stucke: People used to say that dominant companies like Google must be benign because their products and services are free (or low-priced, like Amazon) and they invest a lot in R&D and help promote innovation. Legal scholar Robert Bork argued that Google can’t be a monopoly because consumers can’t be harmed when they don’t have to pay.

I wrote an article for Harvard Business Review revisiting that thinking and asking what harms the data-opolies can pose. I came up with a taxonomy of how they can invade our privacy, hinder innovation, affect our wallets indirectly, and even undermine democracy. In 2018 I spoke to the Canadian legislature about these potential harms and I was expecting a lot of pushback. But one of the legislators immediately said, “Ok, so what are we going to do about it?”

In the last five or six years, we’ve had a sea change in the view towards the data-opolies. People used to argue that privacy and competition were unrelated. Now there’s a concern that not only do these giant tech firms pose a grave risk to our democracy, but the current tools for dealing with them are also insufficient.

I did a lot of research and spoke before many competition authorities and heard proposals they were considering. I realized there wasn’t a simple solution. This led to the book. I saw that even if all the proposals were enacted, there are still going to be some shortcomings.

LP: What makes the data-opolies even more potentially harmful than traditional monopolies?

MS: First, they have weapons that earlier monopolies lacked. An earlier monopoly could not necessarily identify all the nascent competitive threats. But data-opolies have what we call a “nowcasting radar.” This means that through the flow of data they can see how consumers are using new products and how these new products are gaining in scale, and how they’re expanding. For example, Facebook (FB) had, ironically, a privacy app that one of the executives called “the gift that kept on giving.” Through the data collected through the app, they recognized that WhatsApp was a threat to FB as a social network because it was starting to morph from simply a messaging service.

Another advantage is that even though the various data-opolies have slightly different business models and deal with different aspects of the digital economy, they all rely on the same anti-competitive toolkit — I call it “ACK – Acquire, Copy, or Kill.” They have greater mechanisms to identify potential threats and acquire them, or, if rebuffed, copy them. Old monopolies could copy the products, but the data-opolies can do it in a way that deprives the rival of scale, which is key. And they have more weapons to kill the nascent competitive threats.

The other major difference between the data-opolies today and the monopolies of old is the scope of anti-competitive effects. A past monopoly (other than, let’s say, a newspaper company), might just bring less innovation and slightly higher prices. General Motors might give you poorer quality cars or less innovation and you might pay a higher price. In the steel industry, you might get less efficient plants, higher prices, and so on (and remember, we as a society pay for those monopolies). But with the data-opolies, the harm isn’t just to our wallets.

You can see it with FB. It’s not just that they extract more money from behavioral advertising; it’s the effect their algorithms have on social discourse, democracy, and our whole economy (the Wall Street Journal’s “Facebook Files” really brought that to the fore). There are significant harms to our wellbeing.

LP: How is behavioral advertising different from regular advertising? An ad for a chocolate bar wants me to change my behavior to buy more chocolate bars, after all. What does it mean for a company like Facebook to sell the ability to modify a teenage girl’s behavior?

MS: Behavioral advertising is often presented as just a way to offer us more relevant ads. There’s a view that people have these preconceived demands and wants and that behavioral advertising is just giving them ads that are more relevant and responsive. But the shift with behavioral advertising is that you’re no longer just predicting behavior, you’re manipulating it.

Let’s say a teenager is going to college and needs a new laptop. FB can target her with relevant laptops that would fit her particular needs, lowering her search costs, and making her better off as a result. That would be fine — but that’s not where we are. Innovations are focused on understanding emotions and manipulating them. A teenage girl might be targeted not just with ads, but with content meant to increase and sustain her attention. She will start to get inundated with images that tend to increase her belief in her inferiority and make her feel less secure. Her well-being is reduced. She’s becoming more likely to be depressed. For some users of Instagram, there are increased thoughts about suicide.

And it’s not just the data-opolies. Gambling apps are geared towards identifying people prone to addiction and manipulating them to gamble. These apps can predict how much money they can make from these individuals and how to entice them back, even when they have financial difficulties. As one lawyer put it, these gambling apps turn addiction into code.

This is very concerning, and it’s going to get even worse. Data-opolies are moving from addressing preconceived demands to driving and creating demands. They’re asking, what will make you cry? What will make you sad? Microsoft has an innovation whereby you have a camera that will track what particular events cause you to have particular emotions, providing a customized view of stimuli for particular individuals. It’s like if I hit your leg here, I can get this reflex. There’s a marketing saying, “If you get ‘em to cry, you get ‘em to buy.” Or, if you’re the type of person who responds to violent images, you’ll get delivered to a marketplace targeted to your psyche to induce the behavior to shop, let’s say, for a gun.

The scary thing about this is that these tools aren’t being quarantined to behavioral advertising; political parties are using similar tools to drive voter behavior. You get a bit of insight into this with Cambridge Analytica. It wasn’t just about targeting the individual with a tailored message to get them to vote for a particular candidate; it was about targeting other citizens who were not likely to vote for your candidate to dissuade them from voting. We’ve already seen from the FB files that the algorithms created by the data-opolies are also causing political parties to make messaging more negative because that’s what’s rewarded.

LP: How far do you think the manipulation can go?

MS: The next frontier is actually reading individuals’ thoughts. In a forthcoming book with Arial Ezrachi, How Big Tech Barons Smash Innovation and How to Strike Back, we talk about an experiment conducted by the University of California, San Francisco, where for the first time they were able to decode an individual’s thoughts. A person suffering from speech paralysis would try to say a sentence, and when the algorithm deciphered the brain’s signals, the researchers were then able to understand what the person was trying to say. When the researchers asked the person, “How are you doing?” the algorithm could decipher his response from his brain activity. The algorithm could decode about 18 words per minute with 93 percent accuracy. First, the technology will decipher the words we are trying to say, and identify from our subtle brain patterns a lexicon of words and vocabulary. As the AI improves, it will next decode our thoughts. Turns out that FB was one of the contributors funding the research — and we wondered why. Well, that’s because they’re preparing these headsets for the metaverse that not only will likely transmit all the violence and strife of social media but can potentially decode the thoughts of an individual and determine how they would like to be perceived and present themselves in the metaverse. You’re going to have a whole different realm of personalization.

We’re really in an arms race whereby the firms can’t unilaterally afford to de-escalate because then they lose a competitive advantage. It’s a race to better exploit individuals. As it has been said, data is collected about us, but it’s not for us.

LP: Many people think more competition will help curtail these practices, but your study is quite skeptical that more competition among the big platform companies will cure many of the problems. Can you spell out why you take this view? How is competition itself toxic in this case?

MS: The assumption is that if we just rein in the data-opolies and maybe break them up or regulate their behavior, we’ll be better off and our privacy will be enhanced. There was, to a certain extent, greater protection over our privacy while these data-opolies were still in their nascent stages. When MySpace was still a significant factor, FB couldn’t afford to be as rapacious in its data collection as it is now. But now you have this whole value chain built on extracting data to manipulate behavior; so even if this became more competitive, there’s no assurance then that we’re going to benefit as a result. Instead of having Meta, we might have FB broken apart from Instagram and WhatsApp. Well, you’d still have firms dependent on behavioral advertising revenue competing against each other in order to find better ways to attract us, addict us, and then manipulate behavior. You can see the way this has happened with TikTok. Adding TikTok to the mix didn’t improve our privacy.

LP: So one more player just adds one more attack on your privacy and wellbeing?

MS: Right. Ariel and I wrote a book, Competition Overdose, where we explored situations where competition could be toxic. People tend to assume that if the behavior is pro-competitive it’s good, and if it’s anti-competitive, it’s bad. But competition can be toxic in several ways, like when it’s a race to the bottom. Sometimes firms can’t unilaterally de-escalate, and by just adding more firms to the mix, you’re just going to have a quicker race to the bottom.

LP: Some analysts have suggested that giving people broader ownership rights to their data would help control the big data companies, but you’re skeptical. Can you explain the sources of your doubts?

MS: A properly functioning market requires certain conditions to be present. When it comes to personal data, many of those conditions are absent, as the book explores.

First, there’s the imbalance of knowledge. Markets work well when the contracting parties are fully informed. When you buy a screw in a hardware store, for example, you know the price before purchasing it. But we don’t know the price we pay when we turn over our data, because we don’t know all the ways our data will be used or the attendant harm to us that may result from that use. Suppose you download an ostensibly free app, but it collects, among other things, your geolocation. No checklist says this geolocation data could potentially be used by stalkers or by the government or to manipulate your children. We just don’t know. We go into these transactions blind. When you buy a box of screws, you can quickly assess its value. You just multiply the price of one screw. But you can’t do that with data points. A lot of data points can be a whole lot more damaging to your privacy than just the sum of each data point. It’s like trying to assess a painting by Georges Seurat by valuing each dot. You need to see the big picture; but when it comes to personal data, the only one who has that larger view is the company that amasses that data, not only across their own websites but in acquiring third-party data as well.

So we don’t even know the additional harm that each extra data point might be having on our privacy. We can’t assess the value of our data, and we don’t know the cost of giving up that data. We can’t really then say, all right, here’s the benefit I receive – I get to use FB and I understand the costs to me.

Another problem is that normally a property right involves something that is excludable, definable, and easy to assign, like having an ownership interest in a piece of land. You can put a fence around it and exclude others from using it. It’s easy to identify what’s yours. You can then assign it to others. But with data, that’s not always the case. There’s an idea called “networked privacy” and the concern there is that choices others make in terms of the data they sell or give up can have then a negative effect on your privacy. For example, maybe you decide not to give up your DNA data to 23andMe. Well, if a relative gives up their DNA, that’s going to implicate your privacy. The police can look at a DNA match and say, ok, it’s probably someone within a particular family. The choice by one can impact the privacy of others. Or perhaps someone posts a picture of your child on FB that you didn’t want to be posted. Or someone sends you a personal message with Gmail or another service with few privacy protections. So, even if you have a property right to your data, the choices of others can adversely affect your privacy.

If we have ownership rights in your data, how does that change things? When Mark Zuckerberg testified before Congress after the Cambridge Analytica scandal, he was constantly asked who owns the data. He kept saying the user owns it. It was hard for the senators to fathom because users certainly didn’t consent to have their data shared with Cambridge Analytica to help impact a presidential election. FB can tell you that you own the data, but to talk with your friends, you have to be on the same network as your friends, and FB can easily say to you, “Ok, you might own the data, but to use FB you’re going to have to give us unparalleled access to it.” What choice do you have?

The digital ecosystem has multiple network effects whereby the big get bigger and it becomes harder to switch. If I’m told I own my data, it’s still going to be really hard for me to avoid the data-opolies. To do a search, I’m still going to use Google, because if I go to DuckDuckGo I won’t get as good of a result. If I want to see a video, I’m going to go to YouTube. If I want to see photos of the school play, it’s likely to be on FB. So when the inequality in bargaining power is so profound, owning the data doesn’t mean much.

These data-opolies make billions in revenue from our data. Even if you gave consumers ownership of their data, these powerful firms will still have a strong incentive to continue getting that data. So another area of concern among policymakers today is “dark patterns.” That’s basically using behavioral economics for bad. Companies manipulate behavior in the way they frame choices, setting up all kinds of procedural hurdles that prevent you from getting information on how your data is being used. They can make it very difficult to opt out of certain uses. They make it so that the desired behavior is frictionless and the undesired behavior has a lot of friction. They wear you down.

LP: You’re emphatic about the many good things that can come from sharing data that do not threaten individuals. You rest your case on what economists call the “non-rivalrous” character of many forms of data – that one person’s use of data does not necessarily detract at all from other good uses of the data by others. You note how big data firms, though, often strive to keep their data private in ways that prevent society from it for our collective benefit. Can you walk us through your argument?

MS: This can happen on several different levels. On one level, imagine all the insights across many different disciplines that could be gleaned from FB data. If the data were shared with multiple universities, researchers could glean many insights into human psychology, political philosophy, health, and so on. Likewise, the data from wearables could also be a game-changer in health, giving us better predictors of disease or better identifiers of things to avoid. Imagine all the medical breakthroughs if researchers had access to this data.

On another level, the government can lower the time and cost to access this data. Consider all the data being mined on government websites, like the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It goes back to John Stuart Mill’s insight that one of the functions of government is to collect data from all different sources, aggregate it, and then allow its dissemination. What he grasped is the non-rivalrous nature of data, and how data can help inform innovation, help inform democracy and provide other beneficial insights.

So when a few powerful firms hoard personal data, they capture some of its value. But a lot of potential value is left untapped. This is particularly problematic when innovations in deep learning for AI require large data sets. To develop this deep learning technology, you need to have access to the raw ingredients. But the ones who possess these large data sets give it selectively to institutions for those research purposes that they want. It leads to the creation of “data haves” and “have nots.” A data-opoly can also affect the path of innovation.

Once you see the data hoarding, you see that a lot of value to society is left on the table.

LP: So with data-opolies, the socially useful things that might come from personal data collection are being blocked while the socially harmful things are being pursued?

MS: Yes. But the fact that data is non-rivalrous doesn’t necessarily mean that we should then give the data to everyone that can extract value from it. As the book discusses, many can derive value from your geolocation data, including stalkers and the government in surveilling its people. The fact that they derive value does not mean society overall derives value from that use. The Supreme Court held in Carpenter v United States that the government needs to get a search warrant supported with probable cause before it can access our geolocation data. But the Trump administration said, wait, why do we need a warrant when we can just buy geolocation data through commercial databases that map every day our movements through our cellphones? So they actually bought geolocation data to identify and locate those people who were in this country illegally.

Once the government accesses our geolocation data through commercial sources, they can put it to different uses. Think about how this data could be used in connection with abortion clinics. Roe v. Wadewas built on the idea that the Constitution protects privacy, which came out of Griswald v. Connecticut where the Court formulated a right of privacy to enable married couples to use birth control. Now some of the justices believe that the Constitution really says nothing about privacy and that there’s no fundamental, inalienable right to it. If that’s the case, the concerns are great.

LP: Your book is critically appreciative of the recent California and European laws on data privacy. What do you think is good in them and what do you think is not helpful?

MS: The California Privacy Right Act of 2020 was definitely an advance over the 2018 statute, but it still doesn’t get us all the way there.

One problem is that the law allows customers to opt out of what’s called “cross-context behavioral advertising.” You can say, “I don’t want to have a cookie that then tracks me as I go across websites.” But it doesn’t prevent the data-opolies or any platform from collecting and using first-party data for behavioral advertising unless it’s considered sensitive personal information. So FB can continue to collect information about us when we’re on its social network.

And it’s actually going to tilt the playing field even more to the data-opolies because now the smaller players need to rely on tracking across multiple websites and data brokers in order to collect information because they don’t have that much first-party data (data they collect directly).

Let’s take an example. The New York Times is going to have good data about its readers when they’re reading an article online. But without third-party trackers, they’re not going to have that much data about what the readers are doing after they’ve read it. They don’t know where the readers went–what video they watched, what other websites they went to.

As we spend more time within the data-opolies’ ecosystems, these companies are going to have more information about our behavior. Paradoxically, opting out of cross-context behavioral advertising is going to benefit the more powerful players who collect more first-party data – and it’s not just any first-party data, it’s the first-party data that can help them better manipulate our behavior.

So the case for the book is that if we really want to get things right, if we want to readjust and regain our privacy, our autonomy, and our democracy, then we can’t just rely on existing competition policy tools. We can’t solely rely on many of the proposals from Europe or other jurisdictions. They’re necessary but they’re not sufficient. To right the ship, we have to align the privacy, competition, and consumer protection policies. There are going to be times when privacy and competition will conflict. It’s unavoidable but we can minimize that potential conflict by first harmonizing the policies. One way to do it is to make sure that the competition we get is a healthy form of competition that benefits us rather than exploits us. In order to do that, it’s really about going after behavioral advertising. If you want to correct this problem you need to address it. None of the policy proposals to date have really taken on behavioral advertising and the perverse incentives it creates.

- By Gus Leonisky at 3 Jul 2022 - 11:08am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the economy of fear and insecurity……..

Economics presents itself as a rational science dealing with objective measures and quantitative approaches, but astute observers have long recognized its suffusion with magical, fantastic, irrational, and unconscious elements. That makes it fertile ground for those who study human psychology.

Contemporary discussions of economics and psychology focus mostly on behavioral economics, while psychoanalysis, the branch ostensibly dedicated to heightening awareness of the unconscious, has made far fewer appearances in the conversation. More than half a century ago, thinkers like Norman O. Brown and Herbert Marcuse gained wide appeal with their dives into the hidden recesses and unconscious motivations of economics, but as Sigmund Freud began to fall out of favor with academics in the 1960s, psychoanalytic approaches have been pushed aside or rebranded – despite the fact that a great deal of recent scientific research supports Freud’s concept of the unconscious.

As we grapple today with economic systems that seem ever more destructive to human wellbeing, might it be time to reconsider whether psychoanalysis has something useful to say about the dismal science?

The name of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, redolent of mystical and esoteric concerns, would probably sound particularly out of place at an economic conference. But in his book For Love of the Imagination: Interdisciplinary Applications of Jungian Psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst and psychology professor Michael Vannoy Adams shows how Jung’s special attention to images — to making them conscious and understanding their meaning and influence — can help us glean what lies in the shadow of contemporary capitalism.

Adams’ starting point is Adam Smith’s image of the invisible hand, that legendary representation of the unseen force that arranges the economically self-serving actions of individuals into collective benefits. In Adams’ view, the invisible hand is not only a key idea in economics, but “the most important image of the last 250 years” — as paramount to capitalism as the hammer and sickle image is to communism. In Jungian terms, it is archetypal. “No other image so pervades, so dominates, the modern world,” asserts Adams.

He points out that as images go, the invisible hand is an odd one. You can’t really visualize it. Nevertheless, as Adams reminds us, the invisible hand image was circulating long before Smith used it in works ranging from Homer to Voltaire to indicate ghostly or divine forces that intervene in human affairs. Literary scholars note that around the time of Smith’s usage, invisible hands were popping up in gothic novels to slam doors and otherwise move the human plot along. Adams points to an especially evocative version of the hand cited in A.O. Hirschman’s The Passions and the Interests – the reproduced illustration of a celestial, immaterial hand squeezing a human heart beneath the motto, “Affectus Comprime” or, in Hirschman’s translation, “Repress the Passions!” A psychoanalytic image if there ever was one.

As Adams indicates, when Smith first mentions the hand in a treatise on astronomy (in an essay unpublished during his lifetime but probably written before 1758), it was a mythological image — the hand of Jupiter moving celestial bodies in the heavens. Later, this hand becomes an economic hand, mentioned first in the Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759 and then again in The Wealth of Nations in 1776.

Smith construes the economic invisible hand as the influence that leads individuals who pursue a private interest to promote the public good without realizing it. In the Theory of Moral Sentiments, in outlining a case in which a rich landowner ends up employing laborers through his spending on luxury, Smith illustrates that the hand helps the wealthy, in spite of their “insatiable desires,” to share some of their wealth with the poor. Later, in The Wealth of Nations, he describes the hand in a section on trade, suggesting that it guides merchants and manufacturers acting in their own interest for profit to unintentionally produce positive outcomes for all.

Thus, by some audacious magic, the touch of the invisible hand transmutes selfishness into a virtue. This, as Adams puts it, constitutes a “moral inversion” – a turning upside down of a long tradition of viewing selfishness as one of the least desirable human traits. As Adams sees it, the effects of this inversion on human affairs have been profound.

Through Adams’ Jungian analytical lens, the invisible hand can be seen wiping away guilt. Under its influence, a person can feel innocent while acting greedily and indulging in what was previously known as one of the seven deadly sins. In Jungian terms, what happens when we do not recognize our guilt is that we tend to project it onto others as a shadow, the emblem of our unresolved moral conflicts. In free-market systems, the poor are made culpable, blamed for their situation and failure to act in ways that increase their wealth. The poor are assigned guilt for the self-interested actions of the rich.

Adams notes that the hand serves a religious function, too, namely in its representation of the god of the market, the god long worshipped by economists. He views this god as deus absconditus – one that, like the form of the Biblical Yahweh, is hidden and concealed. In another sense, deus absconditus is a god who is absent when people are in extreme trouble. Or a god that is unknowable or incomprehensible. Why, for example, is an invisible hand even necessary if selfish behavior naturally produces beneficial social results?

Adams notes that like Yahweh, the image of the invisible hand privileges the unseen over the seen, the abstract over the embodied, and the intellect over the senses. This function seems to pervade economics, where practitioners have often fallen in love with abstract models that have blinded them to what can be readily seen in reality, particularly the poverty and suffering of actual embodied, living beings. The hand as market god also becomes a deus ex machina like the one lowered onto the stage in ancient dramas to decide the final result of the play, or, more broadly, the mechanism that brings about a solution to a seemingly insoluble problem. In this way, the invisible hand manipulates the economy both divinely and mechanistically. Whatever the economic problem, however thorny, the invisible hand is the only solution: TINA – There Is No Alternative. To speak out against the god of the market is to have your credibility questioned, to commit heresy. For worshippers of the hand, the market has infinite wisdom to behave the way it does.

The market god, observes Adams, is a jealous god, and like Yahweh, will have no other gods before him. If the government seeks to intervene in the divine and benevolent market, then it must be a devil. This image of the market god, according to Adams, allows economists to repress the actual experience of economic crises by summoning the mantra that governmental intervention is never necessary. Market imperfections are thus consigned to the oblivion of what Adams calls the “economic unconscious.” The monopoly of the market god crowds out other images, warns Adams, images that might help orient us towards values like selflessness.

Adams points out that in obviating the necessity of government regulation, the hand dispenses with any human accountability for the economy. Eventually, in the extreme vision of neoliberalism, every inch of human society is in the grip of the hand, with the privatization of everything from medicine to education. The market renders governments unnecessary except to protect the interests of the capitalists, which leads to vast infusions of money from corporations and rich individuals to control the state and enhance their power. The invisible hand in unregulated markets seems to do the opposite of what Smith described – guiding activity that tends to benefit only a few.

Like the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-8, the coronavirus pandemic has discredited the ideology of the invisible hand, illustrating how relentlessly selfish activity produces not social benefits, but social destruction. The Covid crisis revealed how the degeneration of public services renders capitalist societies more vulnerable to disruption and less resilient. The visible hand of the government has returned through fiscal stimulus, benefits to unemployed workers, and monetary policy. There is apostasy afoot, but that does not mean the market god is defeated. Witness the current flurry of arguments coming from many Republicans and, recently, Jeff Bezos, blaming high inflation on Biden’s American Rescue Plan and government stimulus checks, as if supply chain problems and monopolistic practices have nothing to do with it. As if belief in the unquestioned wisdom of the market god doesn’t result in billions of people suffering a mean and miserable existence.

There is plenty of talk in the air about the possibility of recession – perhaps we should also be concerned about ongoing repression. In 1957, Jung issued this warning about the failure to recognize the shadow and understand the operations of the unconscious:

“One can regard one’s stomach or heart as unimportant and worthy of contempt, but that does not prevent overeating or overexertion from having consequences that affect the whole man. Yet we think that psychic mistakes and their consequences can be got rid of with mere words, for “psychic” means less than air to most people. All the same, nobody can deny that without the psyche there would be no world at all and still less a human world. Virtually everything depends on the human soul and its functions. It should be worthy of all the attention we can give it, especially today, when everyone admits that the weal or woe of the future will be decided neither by the attacks of wild animals nor by natural catastrophes nor by the danger of worldwide epidemics but simply by the psychic changes in man.”

Early psychoanalyst Otto Gross, a close associate and influencer of Jung, argued that investigations of the unconscious are the necessary groundwork for any kind of revolution or moral restoration. He points us to the project of liberating the repressed values of mutual aid and cooperation that human beings are born with. Only then can we wave goodbye to the invisible hand.

READ MORE:

https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/what-does-capitalism-repress-a-jungian-perspective

READ FROM TOP.

SEE ALSO:

they know where you live………..

adam came from eve….

why the news is not the truth……….

saving the rich from poverty…...

educating a brave person……..

of monkeys and war merchants with medals…...

economic disinformation…...FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............................

sanctioning your brains…...

BY Clayton Fox

The media, and the people who work in and around it, the Blue Checks™ of Twitter, have upped the ante over the past few years regarding how far they are willing to go to enforce various preferred narratives.

Pick any major story of the past three years—e.g. Lab Leak, Jussie Smollett, Russiagate, Ukrainian Biolabs, Ivermectin, Hospitalizations From COVID v. With Covid, January 6th, ‘Transitory’ Inflation, and of course Hunter’s Laptop—and you will find absolutely hysterical narrative pushing up front followed by retractions, corrections, and outright denials as reality became undeniable.

In the meanwhile, our civilization was ripped apart, our citizens were gaslit and impoverished, and in countries across the Western world, innocent people were removed from polite society, branded as lepers, and fired from their jobs.

Why? Because there is one story that just won’t die and for which no corrections have been issued—the shibboleth that vaccination can prevent infection, transmission, and help “end” COVID.

While there is never an excuse for hateful rhetoric towards, and intervention in, the personal medical choices of law-abiding Americans, perhaps one could have, kinda sorta, understood the campaign if the new vaccines had provided long-lasting immunity and prevented community transmission. They do not.

Early on we were told: “Nine out of ten [vaccinated] people won’t get sick” (Columbia University feat. Run-DMC, February 12th, 2021, no this is not a joke); “Vaccinated people do not carry the virus, don`t get sick” (Dr. Rochelle Walensky, March 29th, 2021); “When people are vaccinated, they can feel safe that they are not going to get infected” (Dr. Anthony Fauci, May 17th, 2021).

And by mid-summer, 2021, we were still being told that unequivocally, these vaccines were a resounding success worthy of uncritical support. On July 27th in Scientific American, Dr. Eric Topol wrote, “Vaccination is the closest thing to a sure thing we have in this pandemic.” Not to be outdone, Dr. Anthony Fauci of the NIAID told CBS on August 1st, that the unvaccinated were responsible for “propagating this outbreak.”

But on July 29th, 2021, the Washington Post reported a scoop that the CDC was privately acknowledging that the vaccinated could spread COVID as easily as the unvaccinated. Occasionally, they are forced to report inconvenient facts. And August 5th, CDC Director Walensky told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer that, “They continue to work well for Delta, with regard to severe illness and death — they prevent it. But what they can’t do anymore is prevent transmission.”

While there is a mountain of medical literature available demonstrating quite clearly the failure of these vaccines to prevent infection and transmission, the August 5th declaration from the CDC Director should have made clear that being vaccinated is contributing in no way to the safety of others, nor to the eradication of this virus.

In fact, Israeli Health Minister Nitzan Horowitz was even caught on tape in September of last year explaining that the use of the Israeli Green Pass wasn’t intended to make a difference epidemiologically, but because it would help convince people to get vaccinated. And even vaccine poobah Bill Gates admitted in a late 2021 interview, that, “We got vaccines to help you with your health, but they only slightly reduce the transmissions.”

So there should be no question that continuing to suggest in any way that these shots are a panacea, and that those who refused to get them were plague spreaders, should have been thoroughly trashed by Fall 2021.

Nonetheless, on September 24th President Joe Biden coined his now famous phrase “a pandemic of the unvaccinated.” To our north, Prime Minister Trudeau called the unvaccinated science deniers, misogynists, and racists, and asked rhetorically whether Canadians should “tolerate” them.

And during the first week of January 2022, while kicking the unvaccinated out of French daily life and public spaces, French President Emmanuel Macron said he wanted the measures to “piss off” his unvaccinated citizens. With world leaders speaking this way, it’s no wonder so many Blue Check™ elites took up the banner!

Prominent media figures like Amy Siskind, Pulitzer Prize winner Gene Weingarten, and more have come out of the woodwork in recent months to share with us their enthusiasm for medical discrimination. Noted neurotic Howard Stern is all in on forced vaccination due to what must be his own debilitating fear of his mortality. Bill Kristol says the unvaccinated have “blood on their hands.”

David Frum, heir to Maimonides, writes, “Let the hospitals quietly triage emergency care to serve the unvaccinated last.” Charles M. Blow was “furious” at the unvaccinated. CNN contributor Dr. Leana Wen suggested that the unvaccinated should not be allowed to leave their homes. The Ragin’ Cajun even wants to punch the unvaccinated in the face!

All of the above links/stories were posted after Dr. Walensky’s unequivocal announcement that the vaccines do not prevent transmission.

And all of the self-satisfied segregationists are supported in their vitriol by the Blue Checks™ of the Medical Establishment, like Dr. Paul Klotman, President and Executive Dean of the Baylor School of Medicine, who said on camera back in January that he isn’t polite to friends and family who aren’t vaccinated. “Keep them away. I don’t do it respectfully, I tell them to stay away, and teach them a lesson.” Less vitriolic but equally problematic, the WHO’s COVID-19 “technical lead” Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove continued to push the lie that vaccination can prevent outbreaks as recently as January 26th, 2022. She is, as well, a Blue Check™. And yes, Dr. Anthony Fauci is still at it, even as of April 14th, 2022, telling MSNBC that harsh Chinese lockdowns could be used to get the population vaccinated so that “When you open up, you won’t have a surge of infections.”

The examples are legion. Blue Checks, Medical Blue Checks, Times Columnists, Radio Jocks, Presidents, and Prime Ministers have all espoused misinformation and/or hate speech regarding vaccination status. But they are all given intellectual cover by the official reporting of the fourth estate. Even in the face of all the evidence that there is no epidemiological basis for discrimination, our intellectual betters in the legacy media press onward the canard.

On August 26th, the Toronto Star ran an article entitled, “When it comes to empathy for the unvaccinated, many of us aren’t feeling it.” Then, on December 22nd, published an explainer which stated that two doses won’t stop you from spreading COVID-19. Comme ci, comme ca.

Back in February, MSNBC political contributor Matthew Dowd shared his insight that the unvaccinated do not believe in the United States Constitution, because if they did, they would get vaccinated for “We The People.” For the common good.

An examination of the New York Times reveals three articles written this year which overtly continue supporting the idea that the vaccines prevent transmission. First, on January 29th in a piece entitled, “As Covid Shots For Kids Stall, Appeals Are Aimed At Wary Parents,” the author cites “public health officials” who say that to aid in “containing” the pandemic, kids must also be vaccinated. (It is worth mentioning that the current vaccines and boosters being distributed were designed in February 2020 to provide an immune response to a version of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein circulating prior to that, not entirely similar to what is circulating now.)

Then February 23rd, in a hit piece on the Surgeon General of Florida Dr. Joe Ladapo, the Times writes, “When public health officials across the country were urging vaccines as a way to end the pandemic, Dr. Ladapo was raising warning flags about possible side effects and cautioning that even vaccinated people could spread the virus.”

So, Dr. Ladapo was correct?

Finally, in a piece about Novak Djokovic published March 3rd, they write, “Djokovic was the only player ranked in the top 100 in Australia who had not received a Covid-19 vaccination, which experts have long said will not eradicate the virus unless most of the population receives one.”

They do not address the question of how a vaccine which does not prevent transmission can eradicate a virus. And they won’t. As Israeli Health Minister Horowitz candidly admitted, none of this is about epidemiology.

And even when mainstream media tacitly acknowledges the failures of the vaccines to prevent transmission, they skillfully elide the significance of this fact in order to allow them to continue to scapegoat the unvaccinated. In a dazzling display of sophistry, Time Magazine moved the Overton window in this January 12th, 2022 piece, “These Charts Show That COVID-19 Is Still A Pandemic of the Unvaccinated.”

The author states that due to the rapidly narrowing gap between cases in the vaccinated and unvaccinated, some readers might think that the phrase “pandemic of the unvaccinated” is no longer justifiable. But with the grace of a ballerina, Time goes on to tell us that because the vaccines are still showing efficacy against severe illness, the phrase is still kosher. If an unvaccinated person gets sicker than his vaccinated neighbor who contracted COVID at a fully vaccinated wedding, that unvaccinated person is still the problem!

New York Magazine isn’t lacking in similar gymnastics. On February 16th of this year, Matt Stieb published a piece entitled, “Is Kyrie Irving Going to Get Away With It?” Irving is the Brooklyn Nets player who famously chose not to be vaccinated, and has become a fetish object for the Covidian Left. Stieb acknowledges that Irving’s vaccinated teammates were getting COVID at such high rates that it forced Nets management to allow Irving back to play in away games but still calls the New York City ban on unvaccinated athletes “a rare public health mandate with real teeth.”

Just seven days later on February 23rd, Will Leitch, in the same publication, sighs, “Unfortunately, It’s Time to Let Kyrie Irving Play in New York.” He outlines all the reasons why epidemiologically it makes no sense to prevent athletes like Irving and Novak Djokovic from participating, but says, “It would feel like they got away with all their bullshit.” And also, they are “annoying.”

And this barely concealed hatred for the unvaccinated from media and government and Big Tech—even in the rare moments when writers such as Leitch acknowledge the failure of the vaccines to prevent transmission—has real consequences. People have lost their jobs. People have been arrested for trying to go to a movie theater.

Families got kicked out of restaurants, and patrons either cheered or remained indifferent, which is worse. A teenage boy at an uber-progressive and expensive Chicago prep school committed suicideafter being bullied over an incorrect rumor he was unvaccinated. The stench of bad journalism rots people’s basic decency.

A January Rasmussen poll found that, “Fifty-nine percent (59%) of Democratic voters would favor a government policy requiring that citizens remain confined to their homes at all times, except for emergencies, if they refuse to get a COVID-19 vaccine…Forty-five percent (45%) of Democrats would favor governments requiring citizens to temporarily live in designated facilities or locations if they refuse to get a COVID-19 vaccine…”

As well as, “Twenty-nine percent (29%) of Democratic voters would support temporarily removing parents’ custody of their children if parents refuse to take the COVID-19 vaccine.” Unfortunately, these disturbing results are politically lopsided, but it’s no surprise when you consider who the readers of most legacy media platforms are.

The saddest thing is that these media outlets and their flag bearers really think their readers are all morons. The New York Times believes that, in the midst of the Omicron wave as boosted person after boosted person was getting COVID, they could tell you these particular vaccines are still the way to eradicate this thing, and expect you to deny reality and nod your head.

It calls to mind the quote attributed to Solzhenitsyn (or Elena Gorokhova), “The rules are simple: they lie to us, we know they’re lying, they know we know they’re lying, but they keep lying to us, and we keep pretending to believe them.”

We have ceded the better angels of our common cerebrum to people who may not have our best interests at heart, and a sycophantic laptop class who gleefully endorses their diktats and “fact-checks.” Collectively: Sophistry Inc.

Their behavior, endorsed by every single entity which holds power in our society, is destroying us, and has already poisoned us such that there may be no antidote. Yes, first they came for the unvaccinated, but that doesn’t mean they won’t come for you next.

READ MORE:

https://brownstone.org/articles/the-insufferable-arrogance-of-the-constantly-wrong/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!