Search

Recent comments

- precious water....

2 hours 51 min ago - black gold....

3 hours 6 min ago - recognized....

11 hours 45 min ago - dear friends.....

13 hours 28 sec ago - war criminals.....

13 hours 56 min ago - aussieoil.....

16 hours 4 min ago - sobering....

16 hours 47 min ago - iran's....

18 hours 18 min ago - blind interceptors....

18 hours 37 min ago - ARTIFINTEL....

20 hours 16 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

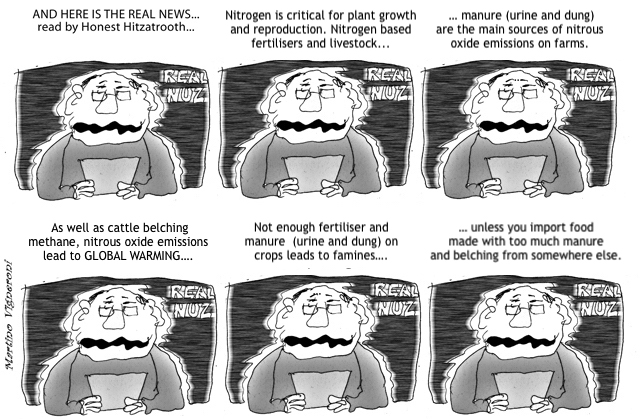

the belching-and-dung-from-somewhere-else problem….

Farmers in the Netherlands are protesting on a scale unheard of in their country. They are furious about a government proposal that may put many of them out of business. Dutch farmers argue the government’s true aim is to seize their highly valuable farmland. They are protesting under the slogan “No farmers, no food” to warn of the dangers of giving up domestic food-supply independence to rely on imports instead.

The origin of the crisis is a 2019 ruling by the highest administrative court in the Netherlands. It ruled that measures the Dutch government had taken to reduce emissions of nitrogen oxide and nitrogen ammonia were not in compliance with European Union rules.

BY Emma Freire

In June, the Dutch government responded to the court’s ruling with a proposal that says reducing the number of livestock in the country is the only way to significantly cut nitrogen emissions. Nitrogen ammonia is produced by livestock.

The Netherlands has a large farming sector. The country has roughly the same land area as Maryland but is the world’s second largest exporter of agricultural products by value, after America.

The farmers started protesting after the court’s ruling in 2019, but the issue mostly went to the back burner when the pandemic hit. The government offered voluntary buyouts of farms but there was little uptake.

The problem came to the forefront again last September, when a leaked government report presented several scenarios, including forced sales of farms. In June, Christianne van der Wal, cabinet minister for nature and nitrogen, said, “That strong measures are needed is a fact. Nitrogen emissions must go down.”

That prompted the farmers to start protesting anew. They deployed tractors to block supermarket distribution centers. This quickly led to empty shelves. Farmers say this gives people a forestate of what will happen when Dutch farms are shut down.

The farmers have also been blocking highways and parking their tractors outside businesses they claim emit more nitrogen oxide and nitrogen ammonia than they do. More is on the way. “We are going to continue protesting, but in a way the Netherlands has never seen before!” said farmer William Schoonhoven at a makeshift press conference in the town of Eerbeek on July 8.

The government has offered talks, but it has already announced that the goal of reducing nitrogen emissions is not open to discussion. Under those conditions, the farmers have refused to come to the table.

Many of the farmers believe the government is using nitrogen emissions as cover for a landgrab. The Netherlands is one of Europe’s most densely populated countries, and the value of the farmland is astronomical. Some of them have pointed to a U.N. agreement called Agenda 2030 which would overhaul the Dutch economy but requires a great deal of land to achieve its goals.

Member of Parliament Gideon van Meijeren of the far-right party Forum for Democracy articulated that view in a speech to the Dutch parliament:

Nitrogen policy is not about nature, it’s about the farmers’ land. The cabinet has committed itself to an international Agenda 2030 and executing this requires lots and lots of land. To reach so-called climate goals, thousands of mega wind turbines need to be built by 2030. They also want to build 1 million residences by 2030, for people who are not even in the Netherlands yet. Land is needed for this…. The state does not have it, but the farmers do. Two thirds of the land in the Netherlands is used by the agricultural sector—land that the cabinet has set its sights on.

Van Meijeren might be going too far. Given the high value of Dutch farmland, however, it is legitimate to ask whether the government has ulterior motives for trying to seize it. Moreover, given how frequently E.U. rules are flouted by member states, it is suspicious to see this one being singled out for draconian enforcement.

When considering the Dutch government’s approach, it is important to understand what a disturbing development this is in Dutch politics. In America, we are used to court orders setting government policy. However, this is alien to the Dutch political tradition. The Netherlands has long been famous for its consensus-based decision-making process, called the “polder model.”

In the polder model, important decisions require a consensus from elected officials and citizens. The Dutch have a multi-party system which invariably requires forming a coalition government. The parties in the governing coalition negotiate policies with each other, but they also need to get a certain degree of buy-in from opposition parties.

This ensures stability. Disruptive mass protests are rare in the Netherlands. The polder model gives citizens the sense that their concerns are taken seriously. The government’s plan for reducing emissions by shutting down the farms is a violation of the tradition of the polder model. There was no serious discussion with the farmers and nothing close to consensus has been reached.

This may well be the first example of what post-Covid-19 governance will look like in the Netherlands. The pandemic allowed the government to do things like impose digital vaccine passports and announce a surprise Christmas lockdown on December 18, 2021. The government is now rolling out its Covid-19 playbook again for nitrogen emissions. This is a “crisis” and, thus, it overrides the need for consensus.

The farmers’ protests also highlight the corrosive impact America’s example has on other countries’ politics. It is well known that America exports our popular culture to rest of the world, but, unfortunately, we also export our unhealthy political discourse. For example, some of the farmers have been protesting outside the houses of government officials.

This would have been unthinkable in the Netherlands a few years ago. But Dutch people watch online videos of Americans protesting at the homes of Supreme Court Justices. They see this is not condemned—and is, in fact, is practically endorsed—by the White House.

Meanwhile, the Dutch media has copied the American media’s practice of trotting out so-called experts to silence dissent. The farmers argue that closing them down is dangerous because the country will lose its food-supply independence. But experts have been informing the Dutch public that it makes no difference whether food is produced domestically or imported.

If the farmers continue with their protests, they may yet prevail. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy is not in a strong position. At his party’s annual conference in June, a majority of delegates voted for a motion to condemn the government’s plans.

Rutte’s governing coalition consists of four parties. Only of them, D66, strongly supports the current nitrogen emissions policy. D66 is one of the most progressive parties in the Netherlands. They were the driving force behind legalizing euthanasia. Today, D66 has also put climate change at the center of their platform. The two other parties in the coalition, the Christian Democratic Appeal and the Christian Union, have large constituencies in the agricultural sector. They are facing a backlash.

If the governing coalition collapses over these farm protests, it will trigger a new election. Hopefully the farmers stand their ground. There is a great deal more at stake here than farmland.

READ MORE:

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-dutch-farmers-uprising/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

- By Gus Leonisky at 14 Jul 2022 - 8:05am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a solution…...

From Agriculture Victoria

Nitrogen is critical to plant growth and reproduction. Pasture and crop growth will often respond to an increased availability of soil nitrogen. This situation is often managed through the addition of nitrogen fertilisers.

Nitrous oxide is a powerful greenhouse gas and accounts for 5 per cent to 7 per cent of global greenhouse emissions with 90 percent of these derived from agricultural practices. Nitrogen based fertilisers and livestock manure (urine and dung) are the key sources of nitrous oxide emissions on farms.

Greater efficiency in the capture of nitrogen in products has the greatest impact on reducing nitrous oxide losses, as well as reducing ammonia volatilisation to the atmosphere and nitrate leaching and runoff to groundwater and waterways. Improved nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) has both productivity and profitability benefits.

Nitrous oxide is most likely released from warm, waterlogged soils where there is excess nitrogen in the form of nitrate. Volatilisation of nitrogen as ammonia can also lead to indirect nitrous oxide emissions through redeposition contributing to excess nitrate elsewhere in the landscape.

Farmers can save money, boost pasture and crop production and reduce nitrous oxide losses by carefully planning and implementing best management practices with regards to the 4 Rs — the ‘right’ rate, source, timing and placement of nitrogen fertilisers to match plant needs.

Follow the 4 Rs:

Fertilizer Australia website — Nutrients and Fertilizer Information

Management optionsResearch has estimated that usually 40 percent to 60 percent of nitrogen inputs into cropping and grazing systems, respectively, is lost to the environment. By improving agricultural practices we can reduce these losses, improve productivity and save money.

Match nitrogen supply to crop/pasture demand by:

Time fertiliser application to minimise nitrogen loss:

Determine and improve plant access to nitrogen by improving soil health and nutrient status — see next section on Soils. Adding nitrogen to soils that have inherent limitations to plant growth is unlikely to result in higher productivity and financial gain.

Choose the best type of nitrogen:

Incorporate fertiliser at the top of raised beds or ridges to avoid concentration and losses in furrows and wet areas.

Estimate the methane and nitrous oxide emissions on your farm using a greenhouse gas accounting tool (go to the links to appropriate tools for your type of enterprise).

Summarised version of a Nitrogen cycle in a grazing/cropping system. The Victorian Resources Online website includes a detailed animation explaining the N cycle.

Improving nitrogen fertiliser use efficiencyThere is a growing body of evidence that indicates that significant amounts of applied N fertiliser remains unaccounted for under certain cropping systems and conditions. Unfortunately, this N is often irretrievably lost from the cropping system, representing both a significant cost to growers and the environment.

Agriculture Victoria research scientists have been at the forefront of research into N fertiliser management and N2O emissions in Victoria's cropping industry for over a decade. A variety of field experiments have been established on farms across Victoria's cropping zones to help better understand the issue.

In the high rainfall zone (HRZ) of south-western Victoria, Agriculture Victoria researchers have recorded losses of up to 85 per cent of the N applied in situations where large amounts of N fertiliser were applied at sowing. In some trials around Hamilton, applying N at sowing to soils already naturally high in N, gave no significant increases in crop yield response. Effectively, what this means is that applying N fertiliser in these situations was both a waste of time and money.

In 2017, Agriculture Victoria researchers completed a collaborative, three-year research project into N use efficiency in key Victorian cropping zones.

Lead researcher, Professor Roger Armstrong stated that:

A real standout result of the project was the high number of instances where N fertiliser response was limited. Reducing current rates of fertiliser N input, particularly in the HRZ, where paddocks have experienced a long history of legume pastures, can have minimal impact on productivity while saving growers money. However, of real concern to growers is the large losses of N fertiliser that we recorded. Fertiliser N recovery in the crop, plus that remaining in the soil at harvest, averaged only 71 per cent; it varied from 63 per cent in the HRZ to 76 per cent in the low/medium rainfall regions.

This research indicates that the best strategies to reduce both fertiliser costs and N2O emissions in these systems are to:

Currently, growers and their advisers can only guess the likely amount of In-Crop Mineralisation (ICM) that is occurring in these soils when making predictions about likely amounts of fertiliser that will need to be applied to meet predicted crop demand. However, simple and rapid soil tests are being developed that will allow an accurate assessment of potential N mineralisation rates before sowing.

Two soil tests (Hot KCl and Solvita) show promise as predictors of ICM, both of which can perform better than some of the current 'rules of thumb' used by advisers across the regions but are not currently available commercially.

The project design and key findings from this collaborative three-year research project are summarised in the following attachments and YouTube video:

READ MORE:

https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/climate-and-weather/understanding-carbon-and-emissions/nitrogen-fertilisers-improving-efficiency-and-saving-money

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>