Search

Recent comments

- figurehead....

2 hours 31 min ago - jewish blood....

3 hours 30 min ago - tickled royals....

3 hours 37 min ago - cow bells....

17 hours 29 min ago - exiled....

22 hours 32 min ago - whitewashing a turd....

23 hours 31 min ago - send him back....

1 day 1 hour ago - the original...

1 day 2 hours ago - NZ leaks....

1 day 12 hours ago - help?....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

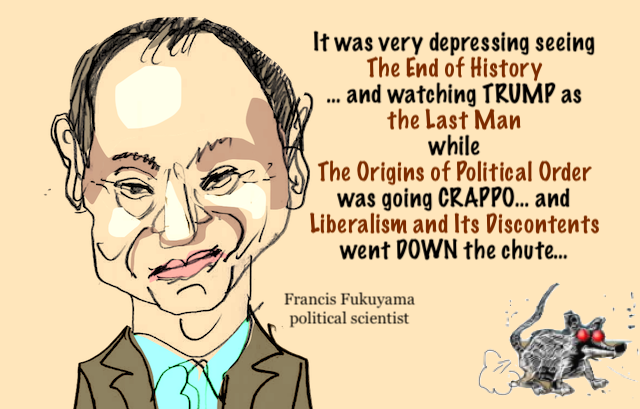

the last man standing.....

Francis Fukuyama is a political scientist, author, and the Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. Among Fukuyama’s notable works are The End of History and the Last Man and The Origins of Political Order. His latest book is Liberalism and Its Discontents. He is also the author of the “Frankly Fukuyama” column, carried forward from American Purpose, at Persuasion.

In this week’s conversation, Yascha Mounk and Francis Fukuyama discuss how Trump’s 2024 victory repudiates the racial grievance theory of 2016; what a second Trump administration will mean for the rule of law at home and abroad; and the lessons the Democratic Party must learn from its defeat.

The transcript and conversation have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Yascha Mounk: Francis Fukuyama, thank you so much for taking the time to process what happened last night together.

Francis Fukuyama: Yeah, I'm very happy to. I spent the evening with my students watching the results as they came in. A lot of them are non-American and so I had to do some explaining about how peculiar the American institution of a national election is, but it meant that I didn't get that much sleep and it was depressing, very depressing, in the end.

I did have a bottle of Venezuelan rum that I was going to open up if Kamala had won. And I had convinced myself based on some of the things that colleagues had said to make me optimistic. But it turned out that this was a complete raising of expectations that made the deflation even more painful, and the bottle of rum is still there.

Mounk: Well, you're a good man for not indulging in the bottle of rum to try and process what happened.

Donald Trump has been elected the 47th president of the United States. He's the second president since Glover Cleveland to be elected in two nonconsecutive terms and take double real estate in the strange numbering of American presidents. He's the first Republican presidential candidate to win the popular vote in 20 years. He will likely have a trifecta of the government, having control of the House and the Senate. And of course, he also has a Supreme Court that is reasonably sympathetic, at least, to his social and cultural program. What does all of that mean for America and for the world?

Fukuyama: Well, I think that it has a much deeper significance than certainly a lot of Democrats were thinking. In 2016, he was elected to the surprise of everybody. And I think that many people, myself included, thought that this was kind of a fluke: that he had not won the popular vote and Hillary was a particularly bad candidate. And there were a lot of reasons that Democrats could give themselves for why that happened.

There was also an expectation that once he became a one-term president and Biden was elected that the world would kind of snap back to something like what it was before 2016. But now it's not just the fact that Trump succeeded in getting reelected. He didn't squeak his way in. He really won a pretty resounding victory. He defeated Kamala Harris in all of the swing states that were up for grabs. They got the Senate. They're very likely, as you said, to get the House as well. They already control the Supreme Court. So conservative power is consolidated in a way that makes the Biden administration look like the fluke, the last gasp of a dying order.

It reminds me a little bit of the 1980 election. I wasn't a particular fan of Ronald Reagan, but he changed the tenor of the time in ways that I didn't expect at the moment of his election. Just to give you one example: I remember when I was a student, Adam Smith was not considered a serious writer and very few political theory people actually tried to study Adam Smith and read his books seriously. After Reagan was elected, all the academics actually got on board with that. It gave a legitimacy to a market economics that really had not existed when I was in college in the early seventies. Then, if you had said, “I want to go to business school,” most of my friends would look down on that person and say “you're just greedy” and so forth. And then after his election, it was okay to go to business school. And in fact people went to business school in droves.

So I think that there's going to be a change in the tone of a lot of American society that will go deeper than just whatever policies Trump tries to enact. But this time around, I'm not quite sure what the leading ideas that guide this are, other than kind of resentment at the educated elites and this sort of thing. But that doesn't really define a positive set of ideas towards which we are moving. And so that's the kind of puzzle that I have right now.

Mounk: I made a somewhat similar argument in my Substack column the morning after the election, which is that this is the beginning of the Trump era. This is a slightly question-begging title because, of course, in many ways we've been obsessed with Trump for 10 years. But I think until the day of the election, it was still possible to hope that Trump would enter the history books as a kind of strange footnote. There was this strange aberration of an election in 2016, and suddenly, you had this figure that really cleaved the political system for 10 years. But he lost the midterms in 2018. He lost his bid for reelection in 2020. The Republican Party didn't do very well in 2022. And then, lo and behold, he managed to win the Republican primary again in 2024. He has earned a much more lasting place in history books, though it’s always difficult to make those predictions. He is going to dominate not just a brief moment, but a political era. It was getting harder to imagine the Republican Party would simply revert to what it was before, but now it is quite clear that Trump owns the party for another four years and very likely that he'll be able to have a major say in who becomes his successor in 2028.

I'm wondering, Frank, about how we should reflect on this as political scientists. In 2016, one quite dominant interpretation of Trump's victory was that it was racial resentment which was driving it—that the voters for Trump really were whites who were resentful about the status that they had enjoyed in society and that was being undermined, and that this was kind of a last gasp. That was the last moment where they could arithmetically make their stand. And so Trump was an instantiation of a tyranny of a minority, and he could only really win by exploiting various ways in which non-white voters are supposedly excluded from the polls and so on. And all of this was comforting because it implied that this was a last-ditch attempt. But it is now clear that this is not just about white resentment, because Trump actually did very well among non-white voters, did very strongly in Florida—which has been a majority-minority state for a long time—and particularly expanded his share of the vote among Latinos. This doesn't feel like the last stand of a dying electorate, at all, since he actually has managed to diversify the Republican electorate in a broad way. And doesn't seem like the tyranny of a minority, because—though tyranny it may turn into—it would be the tyranny of the majority, since it looks like he's clearly on track, as we're recording this, to win the popular vote.

So, do political scientists have to really rethink the story of the last 10 years?

Fukuyama: Yeah, definitely. I really never believed the racial resentment story because it never really corresponded to my observation of what Trump was.

In my book on liberalism, I said that liberalism was damaged by two distortions: one was neoliberalism—this worship of markets, Milton Friedman, and the belief that everything is just a matter of efficiency. And the other distortion is what you might call “woke liberalism,” which is basically identity politics. Both of those things, I think, played an important role in the Trump victory—the repudiation of both of those forms of liberalism. And in a strange way, the fact that Trump got so many black and Hispanic voters on his side was a return to class, or it was a case where class was trumping identity politics, because the people that voted for him were basically working-class blacks and working-class Hispanics, and not educated ones. So the assumption that a lot of people on the left made that minority groups would be attracted to identity politics has been pretty decisively refuted.

The one aspect that is still out there has to do with gender. And that was quite interesting in this election because a lot of the support in those racial and ethnic minority groups was coming from men. They didn't mind that much the anti-immigrant rhetoric. The racial part I think was not that important. I think the gender part was very prominent. In my humble opinion, there's been this massive social change that hasn't really been talked about sufficiently; as a result of the transition to an information economy, you've had this massive move of hundreds of millions of women into the labor force over the last 40 years, which has completely changed the dynamics within families. Especially with working-class families, there are a lot of families that are supported primarily by the wife's income or the girlfriend's income. And that's led to this real sense of anxiety.

Kamala Harris spent all of her time trying to mobilize women around abortion—I would say that that's an issue that most and especially young men really don't care about. And I think that may have played some role in stoking this kind of resentment. So in a way, I think gender has become more important than race as one of the things that divides the country and around which polarization occurs. But I completely agree with you that this old interpretation about the centrality of race is just not right.

I wonder whether you're going to get a kind of reaction to Trump. Because if you just play out in your mind his economic policies, they could lead to one of the biggest economic disasters that this country has ever experienced. He's talked about replacing the income tax with tariffs. He doesn't seem to have any concept of how economically damaging that's going to be. I suspect that the way this will play out is that the moment that he declares a certain level of tariffs against German cars or French wines or whatever, that this time around there's going to be big retaliation. But more importantly, it's going to re-stoke inflation. Inflation is going to go back up to levels that we didn't even see during the post-COVID period.

Trump is very attuned to not doing things that make him look bad. And so that means he's either going to have to drop that particular issue or, rather, what I can imagine is that he'll fire the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. You don't want the government reporting that inflation and unemployment have gone up. But it could be that it leads to a global recession that then deepens into a real depression. What I don't get is these Silicon Valley oligarchs that understand the way economies work—how can they stomach a guy that is promising that kind of economic strategy? I think it's because they don't take it seriously. But maybe you have to actually go through a learning process where you try some of these radical ideas and they really lead to disaster. And then you begin to wake people up to the fact that this is not something that is generally going to help any ordinary person. The only trouble is you have to go through four years of this sort of thing before that learning process really kicks in.

Mounk: Yeah, I think my fundamental model of American politics at the moment—and this election hasn't really changed that—is that both Democrats and Republicans are way out of the American cultural mainstream. They're both way off from where most voters are. And that means that Democrats are in danger of overreaching in ways that they get punished for. But so are Donald Trump and the Republicans. And now that Trump is coming in with a lot of power and a big mandate, he is going to run the risk in purely electoral terms.

I think that's even true of one of his most popular issues: Immigration was clearly one of the things that most unambiguously helped Trump in this campaign. But when you look at Americans' views of immigration, they're rather subtle. Americans value immigrants and value the things that immigrants have brought to America. Most of them believe not just that the present levels of ethnic diversity, which obviously much increased from the past, but further increasing ethnic diversity is a good thing. Only about 15% of Americans think that would be a bad thing. At the same time, Americans are, for understandable reasons, very keen to get control of the southern border and to make sure that the level of illegal immigration is drastically reduced.

Now, the problem, of course, is that when you have very lax policies and high levels of illegal immigration, people say, “clamp down, we want to close the border,” and the moment you start doing the things you actually need to do to clamp down, they start to say, “well, hang on a second, I didn't want this kid to die. I didn't want those kids to be separated from their parents. I didn't want this particular member of the community, who's been here for 25 years and who seems like a very good and reasonable person, to suddenly be taken and sent back to where they came from.” And so I think even on that issue, which was a winning issue of Trump's and which he clearly has a popular mandate—currently opinion polls clearly show that this is true even among the majority of Latinos—he may quite quickly lose public support, nevertheless.

Fukuyama: Well, another problem with that enforcement policy was that the employers won't like it. I mean, they need that low-skill labor, and they don't want to have to police whether someone is in the country legally or not. But the thing is that the policy that Trump has been laying out in this election cycle is so much more extreme than what you just described. Better border enforcement is something that I and many other Trump critics would be very happy with. But he's talking about rounding up 11 million people, putting them in camps, taking them out of their neighborhoods. It's so far beyond any kind of reasonable expectation administratively. We simply don't have the capacity to do anything remotely on that scale. Morally, the idea that you'd go into a neighborhood and basically arrest people that had been in the country for 15, 20 years whose children were all American citizens and put them in a camp somewhere, it's just kind of mind-boggling.

Again, I think that once you confront the reality of what it means to actually carry out the sort of thing that Trump claims he wants, people are going to wake up to the fact that this is a pretty extreme policy—they wanted border enforcement, but they don't want concentration camps.

Mounk: Let's get to the heart of the matter. How dangerous is Donald Trump going to be for America's democratic institutions over the course of the last four years? How should we think about assessing the extent of that danger?

Fukuyama: Well, I think the primary threat is to the rule of law. He's been very clear in the last few months and weeks that he's really out for revenge. He wants to take revenge on all the people that he believes have been prosecuting him and or persecuting him. And I think that this is where Schedule F really matters because, in his first term, he couldn't get his own Justice Department to go after Hillary Clinton, even though he wanted them to. But he understands that that was a weakness of his first term. And I think he's going to put people in key positions in the Justice Department that will enable them to open up investigations.

Let me just give you one concrete example. The head of the IRS is subject to what they call “for cause dismissal,” meaning that he's got to commit some crime or some really overt offense before you can fire him. Schedule F is going to get rid of that. There are hundreds of these “for cause” positions throughout the government. So if Trump can fire the head of the IRS, and put a loyalist in there, then you could open up a tax audit against a journalist or head of an NGO or the NGO itself, that will be incredibly harassing and will tie the organization or the individual up in all sorts of legal fees. So, you're not talking about a Putin-style putting everybody in a gulag, but you are giving the executive incredible power against individuals and against organizations. And I think that that'll be kind of one of the primary lines of attack.

The whole discussion about fascism I thought was a little bit misplaced because that conjures up pictures of concentration camps and then a sort of action on a scale that I don't think we're going to ever see. In terms of replicating Viktor Orbán's behavior in Hungary over the past 15 years, however, I think that's extremely predictable, actually. And I think that that's what the Trump administration is going to look like: this kind of steady, slow erosion of one check and balance against executive power after another. And he’s also angrier in a way that he wasn't in 2016.

Mounk: You made the comparison to Orbán. And I think that in terms of how to understand Donald Trump, that's absolutely right. I think we both agree that we should think of him, roughly speaking, as an authoritarian populist who's comparable to people like Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, or Narendra Modi in India, rather than to try and compare him to past historical figures under the label of fascism.

Now, it is much easier to capture power in a small country with unified political power than a large country with a deeply federally distributed political power. It's much easier to do so in a relatively small economy in which most businesses and media enterprises are reliant on government spending or funding, and so on, than it is in a large, wealthy country in which enterprises are more independent, and in which media companies like The New York Times have millions of subscribers that allow them to work somewhat independently of financial pressures put upon them by the federal government.

Yes, the stress test applied by Trump to these institutions is going to be much harder than it was in 2016. But aren't American institutions also likely to be more resilient than those of Hungary, for example? And if that's the case, and if we have, as I put in a recent article, a very strong force meeting a kind of immovable object, how is this going to play out?

Fukuyama: I think you do have to look at specific institutional rules. For example, I think that the strongest institution was actually the judiciary in Trump's first term. And the reason for that is that we have lifetime appointments of judges. And it's very difficult to change the federal judiciary. He did it in some cases, with retirements and deaths and so forth. But that's something that you can't do. Whereas I think in some countries you basically could retire the entire court within a year. They did that in El Salvador, for example. Bukele got rid of all of the judges in one fell swoop. And it would be much harder to get away with something like that in the United States. That's why I think most of the judiciary didn't go along with the election denialism back in the 2020 election. So, yeah, I think you're right that things are stronger.

But there are also these other weird characteristics of our system right now. What do you make of Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, who all of a sudden decides that he's going to become a political actor? One of the things that I've found really appalling about this election cycle is that a billionaire can just decide to spend hundreds of millions of dollars supporting one particular candidate. In Europe you just don't have that situation. There are individual European countries where you're not even allowed to advertise on television during an election cycle. It's kind of appalling that you can have these private actors that can amass the kind of power that they have and then extend that power into politics.

Mounk: We haven't really touched on the international dimension of all of this yet. Trump is clearly impatient with the Ukraine war and impatient with the support the United States is giving to Ukraine. But is he going to go and try and negotiate some kind of tough deal with Vladimir Putin where he's looking out for the interests of the United States? Or is he going to simply bargain Ukraine away for some other real or perceived benefit that he thinks might be in the interest of the US? I find it hard to tell.

In relation to China, he obviously is generally taking quite a tough stance. At the same time, he said things about Taiwan that undermine confidence that he cares at all about protecting the island's current status. I find it really hard to foretell both what actions he's going to take, and how other countries are going to read them. What's your best attempt at a projection here?

Fukuyama: I think there's less uncertainty about Ukraine. A lot of the Republican Party really doesn't like Ukraine and they think we're on the wrong side of that conflict, as evidenced in the six-month cutoff of all weapons to Ukraine by the House Republicans. And so I think that Trump can probably get a short-term deal with Putin that will freeze the war, so he can come away from it saying, “Look, I promised to stop the war and I did it,” but it will be deeply bad for Ukraine. If they don't have some kind of a NATO guarantee, any ceasefire is really going to just lead to their eventual national demise because the Russians will simply start fighting again the moment they feel that they've rebuilt their forces sufficiently. I think that that's pretty clearly what he intends to do. I think that he also is probably not going to overtly try to pull out of NATO, but he doesn't have to. All he has to do is send signals that he's actually not going to carry through on an Article 5 guarantee, and that's enough to basically weaken the credibility of the alliance, which is really what NATO is all about.

One of the enduring characteristics of Trump in foreign policy is he does not want to use American military force and he does not want to be a president that's going to get America involved in another war, in particular a war with China. Biden's been trying to do this dance where he suggests that yes, we would be willing to fight over Taiwan, and that that will be enough to deter China. I think that a lot of foreign players can see that Trump does not really want to get into a war, that he keeps talking about the danger of World War III and that he's not going to put us in a position to get into World War III. And I think that in a way, this paper tiger dimension of him will be increasingly apparent to people. So he'll talk tough about China. But if he can pull off a deal with them, I think that he would do it at Taiwan's expense. That's the most likely course that he's going to follow.

The other thing is that I suspect he will not raise any objections to anything that Benjamin Netanyahu wants to do in the Middle East. And that's actually something that Trump's got to be careful about, because they're much more likely to get directly involved if the fight between Israel and Iran escalates into a full-scale war. I don't really see exactly how Trump is going to deal with those competing considerations.

Mounk: On foreign policy, I think there's two ways of thinking about the risk that Trump poses. One is that it is likely to have clearly predictable bad effects, right? It is likely to weaken NATO in such a way that Russia is further emboldened in Europe.

The other is a kind of tail-end risk. The problem is that Trump is so unpredictable that perhaps 90% of the time you run his second presidency and things may somehow turn out to be fine, perhaps in part because there's something to the madman theory of foreign relations, in which other countries are going to be wary of trying the United States because they generally don't know how Trump might react. But perhaps the other 10% of the time it goes really, really badly wrong.

Do you think that the danger we're dealing with is both of those? Is it more the former? Is it more the latter?

Fukuyama: People have suggested that his unpredictability might actually be an asset the way Richard Nixon deliberately used unpredictability as a way of getting to a settlement in the Vietnam War. I don't think it works that way with Trump. Nixon had the credibility that he was willing to escalate, and he did escalate in the last few years before the collapse of South Vietnam. The risk of the uncertainty about Trump is whether he will actually do anything. And you could see people being tempted by the belief that he is so averse to using military force that they can actually get away with stuff.

Mounk: What should those who are worried about Donald Trump do in the next year? I have to say that I am a little bit concerned that Democrats will basically rerun the script of 2016 to 2020— that they will bring out the “#resistance” again, and cast not just Donald Trump as a dangerous politician, but also all of his supporters as terrible people. And that they will fail to introspect about the reasons that they have not been able to build a much broader electoral coalition.

All of that might suffice for a few years. For the reasons you outlined earlier, Trump might very well overstep and perhaps that's enough for Democrats to win back the House in 2026, perhaps even to win back the Senate, which might prove more difficult. But it's not clear to me that that will be at all enough to put a lasting end to the Trump era which dawned yesterday.

Fukuyama: Part of it is what Kamala Harris should have done during her brief campaign, and it actually should have started under Biden. The two big issues really that drove people away from the Democratic Party were the border and identity politics. And especially with identity politics, that's something that didn't have to cost any money—having a Sister Souljah moment where you say definitely “I'm not in favor of gender transitions of a twelve-year-old” and make the case about why that's wrong and dangerous and then actually admit that it was a big mistake for Biden not to have tightened control over the border. (Having done it at the last minute meant that nobody believed that he was serious about that.) Just say openly “yeah, that was a mistake and we're not going to make that mistake again if we come back into power.” So that would be at least a start.

Mounk: I have a simpler and cleaner Sister Souljah moment that I suggested Kamala Harris take at the time and that I still regret she didn't. When her candidacy was very quickly elevated, it became clear within 24 hours that she would in fact be the Democratic Party nominee without a real primary process. And all of her supporters started organizing, following the instincts and the practices in their political professional milieu, by race and gender—culminating in the call for White Dudes for Kamala. It was a little bit more self-ironic and a little bit less grating than I imagined it to be, but what a wonderful opportunity this would have been for Kamala Harris to go out and say, “I'm so excited. There's so much support for me. Thank you, everybody who's organizing. But I really would rather that my followers do not organize themselves by race and gender. Let's have calls where everybody does this together.” What a nice way—without alienating anybody in particular, without calling anybody out in a hostile way—to demonstrate “this is not the kind of candidate I want to be.”

Fukuyama: I agree completely. And like I said, border enforcement actually is a serious policy that takes investment and so forth. But this kind of break with foolish identity politics is really costless. It's just making a statement.

And it's too bad that she didn't do that because it really has driven a lot of the opposition. One thing that's pretty clear is that Trump's favorability ratings still are pretty low and they were below Harris's just as an individual. And so I think a lot of the vote for Trump was actually a vote against the Democrats and the fact that they hadn't made these kinds of decisive breaks against things that people don't like about the Democratic Party.

One other thing that I think could be done is an area that I've been focusing on a lot in the last few years, which is building things. One of the things that the left in the United States is famous for is believing that you get legitimacy by adding procedures and regulations that get in the way of actually accomplishing anything. It takes us almost 10 years to get the permitting done for transmission lines to get alternative electricity from Texas and Oklahoma to California. And if you want to solve the housing crisis, especially here in California, you just have got to cut through all of the ridiculous red tape that exists before you can do anything, the way Josh Shapiro did in Pennsylvania when he rebuilt I-95 after it had had that big accident a year or so ago. If a Democrat stood up and said “we have way too many environmental regulations, we really need to cut through all this nonsense and really get things done and go back to building things again,” I think that would also be a very positive message, but it was a route not taken in this campaign.

In the rest of this conversation, Yascha and Frank discuss the left’s fixation on identity politics, and the role it may have played in ceding its cultural advantage—as typified by shows like 30 Rock and The Office—to Donald Trump. This discussion is reserved for paying members...

https://www.persuasion.community/p/francis-fukuyama-on-trump-47

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

“It’s hard to do cartoons without politics…”

Gus Leonisky

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Nov 2024 - 10:38am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

editorial....

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

“It’s hard to do cartoons without politics…”

Gus Leonisky

end of the....

POSTED ON JANUARY 16, 2025As one politician, all too sadly, returns to Washington — and you know just who I mean — another, all too sadly, is leaving. Call it, if not the end of history, then at least the end of something that matters (and, of course, the beginning of who knows what else). Departing is Congresswoman Barbara Lee. She will be remembered forever (at least by me) for, in the immediate wake (and that’s an all-too-appropriate word) of the 9/11 attacks, casting the only vote in Congress — yes, the only one! — against the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, or AUMF, that the rest of the House and Senate passed (420 to 1). It essentially turned the constitutional right to war-making over to the president just as what came to be known as the Global War on Terror began.

For refusing to give George W. Bush and the presidents who followed him a blank check when it came to disastrous rounds of future war-making, she suffered much criticism and abuse. She was called a traitor, even a terrorist. One newspaper labeled her “a long-practicing supporter of America’s enemies.” As she said, looking back years later, “It was a very difficult decision, but I knew that I couldn’t vote for that. And also I knew that, based on my background in psychology, you don’t make hard decisions when you’re upset, when you’re in mourning. You have to think through the implications of any type of major decision. And then I was concerned about the issue of forever wars. It set the stage, and I knew it was going to do that. The military option could be the first option before we tried any other option to settle disputes, to respond to terrorist attacks.”

In some sense, you might say that the vote to send us into that Global War on Terror would end the moment in history following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, when American officials came to consider the U.S. the “sole superpower” on Planet Earth. And you might even say that, so many years later, it also helped set the stage for Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again movement and his first presidency. With the departure of an antiwar congressional great and the return of Trump to the White House — you know, the man who, on January 6, 2020, tweeted to his followers, who had stormed Congress in the wake of his electoral loss, “We love you. You’re very special!,” then adding, “Remember this day forever!” — let TomDispatch regular Andrew Bacevich, author most recently of the novel Ravens on a Wire (a vivid look at the post-Vietnam American military), consider what History may now be signaling to us. Tom

Surprise! What I Learned After "The End of History"

BY ANDREW BACEVICH“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” So declared Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Ah, if only it had proved to be so.

Although my respect for MLK is enduring, when it comes to that upward-trending curve connecting past to present, his view of human history has proven to be all too hopeful. At best, history’s actual course remains exceedingly difficult to decipher. Some might say it’s downright devious (and, when you look around this embattled planet of ours today, from the Ukraine to the Middle East, deeply disturbing).

Let’s consider a specific, very recent segment of the past. I’m thinking of the period stretching from my birth year of 1947 to this very moment. An admission: I, too, once believed that the unfolding events during those long decades I was living through told a discernible story. Although not without its zigs and zags, so I was convinced once upon a time, that story had both direction and purpose. It pointed toward an ultimate destination — so politicians, pundits, and prophets like Dr. King assured us. In fact, embracing the essentials of that story was then considered nothing less than a prerequisite for situating yourself in the ongoing stream of history. It offered something to grab hold of.

Sadly enough, all of this turned out to be bunk.

That became abundantly clear in the years after 1989 when the Soviet Union began to collapse and the U.S. was left alone as a great power on Planet Earth. The decades since then have carried a variety of labels. The post-Cold War order came and went, succeeded by the post-9/11 era, and then the Global War on Terror which, even today, in largely unattended places like Africa, drags on in anonymity.

In those precincts where opinions are manufactured and marketed, an overarching theme informed each of those labels: the United States was, by definition, the sun around which all else orbited. In what was known as an age of unipolarity or, more modestly, the unipolar moment, we Americans presided as the sole superpower and indispensable nation of Planet Earth, exercising full-spectrum dominance. In the pithy formulation of columnist Max Boot, the United States had become the planet’s “Big Enchilada.” The future was ours to mold, shape, and direct. Some influential thinkers insisted — may even have believed — that History itself had actually “ended.”

Alas, events exposed that glorious moment as fleeting, if not altogether illusory. For several reasons — Washington’s propensity for needless war certainly offers a place to start — things did not pan out as expected. Assurances of peace, prosperity, and victory over the foe (whoever the foe it was at that moment) turned out to be false. By 2016, that fact had registered on Americans in sufficient numbers for them to elect as “leader of the Free World” someone hitherto chiefly known as a TV host and real estate developer of dubious credentials.

The seemingly impossible had occurred: The American people (or at least the Electoral College) had delivered Donald Trump to the pinnacle of American politics.

It was as if a clown had taken possession of the White House.

Shocked and appalled, millions of citizens found this turn of events hard to believe and impossible to accept. President Trump promptly proceeded to fulfill their worst expectations. By almost any of the measures habitually employed to evaluate political leadership, he flopped as a commander-in-chief. To my mind, he was an embarrassment.

Yet, however inexplicably, Trump remained to many Americans — growing numbers, it would turn out — a source of hope and inspiration. If given sufficient time, he would redeem the nation. History had summoned him to do so, so his followers believed, fervently and adamantly.

In 2020, the anti-Trump Establishment did manage to scratch out one final chance to show that it was not entirely bankrupt. Yet sending to the White House an elderly white male who embodied the politics of the Old School merely postponed Trump’s Second Coming.

No doubt Joe Biden was seasoned and well-intentioned, but he proved to possess little or nothing of Trump’s mystifying appeal. And when he stumbled, the remnant of the Establishment quickly and brutally abandoned him.

So, four years on, Americans have reversed course. They have decided to give Trump — now elevated to the status of folk hero in the eyes of many — another chance.

What does this head-scratching turn of events signify? Could History be trying to tell us something?

The End of the End of History

Allow me to suggest that those who counted History out did so prematurely. It’s time to consider the possibility that all too many of the very smart, very earnest, and very well-compensated people who take it upon themselves to interpret the signs of our times have been radically misinformed. Simply put: they don’t know what they’re talking about.

Viewed in retrospect, perhaps the collapse of communism did not signify the turning point of cosmic significance so many of them then imagined. Add to that another possibility: Perhaps liberal democratic consumer capitalism (also known as the American Way of Life) does not, in fact, define the ultimate destination of humankind.

It just might be that History is once again on the move — or simply that it never really “ended” in the first place. And as usual, it appears to have tricks up its sleeve, with Donald Trump’s return to the White House arguably one of them.

More than a few of my fellow citizens see his election as a cause for ultimate despair — and I get that. But to saddle Trump with responsibility for the predicament in which our nation now finds itself vastly overstates his historical significance.

Let’s start with this: Despite his extraordinary aptitude for self-promotion, Trump has shown little ability to anticipate, shape, or even forestall events. Yes, he is distinctly a blowhard, who makes grandiose promises that rarely pan out. (If you want documentation, take your choice among Trump University, Trump Airlines, Trump Vodka, Trump Steaks, Trump Magazine, Trump Taj Mahal, and even Trump: the Game.) Barring a conversion akin to the Apostle Paul’s on his journey to Damascus, we can expect more of the same from his second term as president.

Yet the yawning gap between his over-the-top MAGA rhetoric and what he’s really delivered should be instructive. It trains a spotlight on what the “end of history” has actually yielded: lofty unfulfilled promises that have given way to unexpected and often distinctly undesired consequences.

That adverse judgment hardly applies to Trump alone. In reality, it applies to every president since George H.W. Bush unveiled his “new world order” back in 1991, with his son George W. Bush’s infamous 2003 “Mission Accomplished” claim serving as its exclamation point.

Since then, at the national level, American politics, especially presidential politics, has become a scam. What happens in Washington, whether in the White House or on Capitol Hill, no more reflects the hopes of the Founders of the American republic than Black Friday and Cyber Monday express “the reason for the Season.”

In that sense, while Trump’s return to the White House may not be worth celebrating, it is entirely appropriate. It may well be History’s way of saying: “Hey, you! Wake up! Pay attention!”

The Big Enchilada No More

In 1962, former Secretary of State Dean Acheson remarked that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role.” Although a bit snarky, his assessment was apt.

Today, one can easily imagine some senior Chinese or Indian (or even British) diplomat offering a similar judgment about the United States. America’s imperial pretensions have run aground. Yet the loudest and most influential establishment voices — Donald Trump notably excepted — continue to insist otherwise. With apparent sincerity, President Biden all too typically clung to the notion that the United States does indeed remain the planet’s “indispensable nation.”

Events say otherwise. Consider the arena of war. Once upon a time, professing a commitment to peace, the United States sought to avoid war. When armed conflict became unavoidable, America sought to win, quickly and neatly. Today, in contrast, this country seemingly adheres to an informal doctrine of “bomb-and-bankroll.” Since three days after the 9/11 attacks (with but a single negative vote), when Congress passed an Authorization for the Use of Military Force, or AUMF, war has become a fixture of presidential politics, with a compliant Congress issuing the checks. As for the Constitution, when it comes to war powers, it has become a dead letter.

In recent years, U.S. military casualties have been blessedly few, but outcomes have been ambiguous at best and abysmal — think Afghanistan — at worst. If the United States has played an indispensable role in these years, it’s been in underwriting disaster, spending billions of dollars on catastrophic wars that were, from the moment they were launched, of distinctly questionable relevance to this country’s wellbeing.

In his inconsistent, erratic, and bloviating way, Donald Trump — almost alone among figures on the national stage — has appeared to find this objectionable and has proposed a radical course change. Under his leadership, he insists, the Big Enchilada will rise to new heights of glory.

To be clear, the likelihood of the incoming administration making good on the myriad promises contained within its MAGA agenda is close to zero. When it actually comes to setting basic U.S. policy on a more sensible course, Trump is manifestly clueless. Buying Greenland, taking the Panama Canal, or even making Canada our 51st state will not restore our ailing Republic to health. As for the team of lackeys Trump is assembling to assist him in governing, let us simply note that there is not a single figure of Acheson’s stature among them.

Still, here we may find reason for at least a glimmer of hope. For far too long — all my life, in fact — Americans have looked to the White House for salvation. Those expectations have met with repeated, seemingly endless disappointment.

Vowing to Make America Great Again, Donald Trump has, in his own strange fashion, vaulted those hopes to a new level. That he, too, will disappoint his followers, no less the rest of us, is, of course, foreordained. Yet his failure might — just might — bring Americans to rethink and renew their democracy.

Listen: History is signaling to us. Whether we can successfully interpret those signals remains to be seen. In the meantime, brace yourself for what promises to be a distinctly bumpy ride.

https://tomdispatch.com/surprise-2/

READ FROM TOP.

SEE ALSO:

the YD continuum since 2005....

PLEASE DO NOT BLAME RUSSIA IF WW3 STARTS. BLAME AMERICA.